When the Zionist Underground Planted Bombs Outside Baghdad’s Jewish Cafés and Synagogues

|

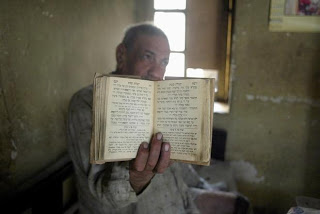

| Yacoub Youssef, an Iraqi Jew, holds his prayer book in his house in Baghdad’s Tanaouine neighborhood, 19 April 2003 |

|

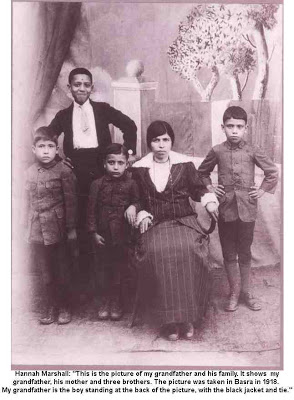

| Iraqi Jewry in Basra |

|

| Nuri e-Said |

|

| Nuri e-Said – Iraq’s pro-British dictator |

An article in Electronic Intifada by Ali Abunimah on what happened in Iraq in 1950-1, when the Zionist underground set off bombs in order to ‘persuade’ Iraqi Jewry to emigrate to Israel, cites an article by Naiem Giladi in 1998. This story has previously been covered in some depth by both David Hirst and Marion Woolfson in the 1970s and 1980s. In fact it was the subject of a libel action in Israel itself. I have therefore decided to summarise the accounts of David Hirst [The Gun and the Olive Branch, Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1977], and Marion Woolfson [Prophets in Babylon – Jews in the Arab World, 1980, Faber and Faber] and drawn on Abbas Shiblak’s ‘Iraqi Jews’ [Saqi Books 2005]. Below is Abunimah’s article ‘Iraqi Jews reject ‘cynical manipulation’ of their history by Israel, Zionists, writer Almog Behar tells EI

One of themes of past and present Israeli governments, articulated by Deputy Foreign Minister Daniel Ayalon in particular, is how what happened to the Palestinian refugees should be balanced by ‘the expulsion’ of Jewish refugees from the Arab countries – Iraq in particular. This has proved, in the words of Almog Behar, who formed the Committee of Baghdadi Jews in Ramat-Gan, the straw that broke the camel’s back.

After his visit to Iraq in 1941, Munya Mardor, an agent of Haganah, wrote that: ‘It had become obvious to me that Iraqi Jewry was not yet ready for mass emigration even if that could be organized’ [Munya Mardor, Strictly Illegal, trans. H.A. G. Shmucklev. Foreword by David Ben-Gurion, Robert Hale, London, 1964, pp. 90] After 15 May 1948, when Iraq was in a state of war with Israel, tension within the Jewish community heightened enormously, and even those Jews who had not welcomed the attentions of the emissaries were looked upon as traitors to their country.

|

| 19th Century alleyway in the Jewish quarter of Baghdad |

This is not surprising. Israel described itself as a Jewish State and claimed patrimony over all Jews, not just those residing in Israel. Coupled with the Farhud in Iraq in 1941 when up to 190 Jews were murdered in the aftermath of a coup against the British [see my review of Gilbert Achcar’s, Arabs & the Holocaust, Journal of Holy Land Studies 10.1 (2011): p.111] it is no surprise that there was tension in the Jewish community of Iraq. Zionism was seeking to further destabilise the Iraqi Jewish community.

On 4th March 1950 an amendment to the existing Ordinance for the Cancellation of Iraqi Nationality was approved by both houses of the Iraqi parliament. [Shiblak, 104] From 5 to 7 March 1950, the Iraqi Parliament suddenly announced that any

Jew who chose to leave Iraq of his own free will could renounce his

citizenship and be free to leave the country. [Schechtman, On Wings of Eagles: The Plight, Exodus and Homecoming of Oriental Jewry, pp. 109-110, Thomas Yoseloff, New York, 1961] But the passage of the law, designed in essence to allow disloyal and disaffected members of the Jewish community to leave, was not the cause of the exodus of Iraqi Jewry. It was intended to expire after one year though Shiblak says that the deadline was continued. [Shiblak 159, 162]

|

| new wing of Meir Elias Hospital, Baghdad 1924 |

Yet the denaturalisation law, which specifically applied to Iraqi Jews (and it was the Americans rather than the British who played an active role in trying to effect the transfer of Iraqi Jews) didn’t, contrary to Zionist claims, have a great deal of effect. After all in Egypt, where the Zionists were stronger and the Muslim Brotherhood active, two-thirds (50,000) Jews remained until 1956 when Israel’s attack on Egypt caused them to emigrate. [Shiblak, 145] Up till the first bomb on 14 April 1950, just 126 people had applied to be registered. It was only after the bomb at the Dar al-Beida coffee-house that thousands began registering. By the end of 1950 some 31,500 were estimated to have left Iraq for Israel though all the evidence is that as 1950 progressed fewer and fewer Jews were seeking to take advantage of the denaturalisation law. It was the attack on the Masuda Shemtov synagogue that proved fatal to the continuation of the Iraqi Jewish community. Here was a direct attack on a Jewish religious centre. The first deaths had occurred. In the 6 weeks before the attack 2,300 Jews had registered for emigration. In the 2 weeks after it 7,600 had registered. [Shiblak pp. 161-2]

Munya Mardor wrote about the enormous efforts which were required to persuade the Jews to embrace Zionism because they were shocked by the thought of doing work which might soil their hands. [Mardor p.92] The fact that – as Mardor made clear – the Jews of Iraq did not want to be ‘rescued’ seemed quite immaterial to the Zionists.

|

| Kurdish Jewish women |

In July 1948 the word ‘Zionism’ was entered into Article Fifty-One of the criminal law and, as a result, hundreds of Jews were placed on trial between June and September 1948. Most of them were fined, others were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment and one was sentenced to death. [Hayyim Cohen, Jews of the Middle East, 1860-1972, Halstead Press, John Wiley, New York, 1973, pp. 31-2.

The Jew who received the death sentence was Shafiq Adas, a rich inhabitant of Basra. According to Rabbi Dr Elmer Berger, there were parallels between the treatment of Jews in Iraq and of Japanese citizens of the United States at the time of Pearl Harbor. The trial was public and conducted with due process of law. Adas had been accused and convicted of ‘trading with the enemy’ for smuggling materials out of Iraq to Israel during the war in Palestine. It was, in fact, reported that Adas, who had made a fortune by dealing in British Army surplus goods, had been tried for supplying weapons to Israel. The Chief Rabbi of Baghdad and Jewish leaders believed that the trial was as fair as it could possibly have been in view of the general atmosphere in the country and they agreed they agreed that a great deal of circumstantial evidence pointed to Adas’s guilt.

There were no specific acts of hostility involving Jews, and no Jewish shops were attacked. The main anger and frustration were directed towards Britain and the United States which were considered to be primarily responsible for the Palestine tragedy and the main supporters of Zionism. [Rabbi Elmer Berger, Who Knows Must Say So, The American Council for Judaism, reprinted by the Institute for Palestinian Studies, 1970, Beirut, p.31. See also Colin Legum in The Observer, 2.2.69.]

In spite of all the efforts of the Zionists to make it appear that the Iraqi Jews were ‘longing for Zion’, an account describes how Zionism was not popular in Iraq even after 1948. While one section of the Baghdad Jewish community consisted of rich merchants and bankers, many of the young people were members of the communist party and a large number of its leaders were Jews. According to one Zionist historian [A. Ben-Yaakov, History of the Jews in Iraq, (Hebrew) Jerusalem 1965, p. 257, Khamsin 5, Raphael Shapiro, Zionism and its Oriental Subjects, Pluto Press, London, 1978, p.16]. a Zionist meeting organized in 1946 was attended by three dozen people, while the Jewish Communist Anti-Zionist Alliance was publishing a daily paper in Baghdad, printing six thousand copies a day.

Referring to the actions of Zionist provocateurs in Iraq a Zionist writer asked:

‘But does the State of Israel have duties towards the Jews who are able, but do not wish, to come here? Moreover, do we have the right to tell them: We know better than you what is best for you – and we shall, therefore, act to make you come here, and we shall perhaps even try to make your position more severe, so that you will have no choice but to immigrate to Israel. Note that this last question is not imaginary. We have confronted it in some very concrete situations and we may still have to confront it again.’ [Uri Harari, ‘Our Responsibility towards Jews in the Arab Countries’ in Yediot Aharonot, 9.2.69. Khamsin].

It is a well-documented, open secret, that the exodus of over 100,000 Jews from Iraq, they formed one-third of the population of Baghdad, a rich and vibrant community, was plotted together by the Israeli government under Ben-Gurion and the British puppet ruler of Iraq, Nuri e-Said, who was hanged in the streets after the revolution of 1958. Israeli agents later testified to having planted bombs to simulate anti-Semitism in order to provoke the flight of Iraqi Jews. In exchange the Iraqi government got to seize their assets.

This was what was termed ‘cruel Zionism’ but it wasn’t exceptional. In Hungary in May 1944, an agreement was reached between Jewish Agency representative Rudolf Kasztner and Adolf Eichman that in exchange for co-operation in the deportation of Hungary’s ½ million Jews to Auschwitz, Kasztner could select the Jewish and Zionist elite and place them on a train which would leave Hungary for safety. This latter is indisputable since the evidence is contained in the trial of the same name in Israel between 1953 and 1958. (see Tony Greenstein, Zionism and the Holocaust, Weekly Worker, June 2006 and Ben Hecht’s Perfidy for an account of the Kasztner Affair.

Zionism, was not so much a Jewish national movement (unlike the anti-Zionist Bund) as a nationalist movement, no different from similar racist and blood and soil movements in Europe, including Nazism itself. If Zionism was prepared to turn its back on and collaborate in the destruction of European Jewish communities, how much more so was it prepared to ensure, by violent means if necessary, that the mass of Jews in the Arab countries emigrated to Israel? What the Israel state required, above all, was a Jewish working class and that was the role of the Arab Jews.

The Jewish state was always far more important than the Jews themselves. Oriental Jewry was no more than despised cannon-fodder for the European settler movement called Zionism. A popular song among Iraqi Jewry ran:

What did you do, Bengurion?

You smuggled in all of us!

Because of the past, we waived our citizenship

And came to Israel.

Would that we had come riding on a donkey and we

Hadn’t arrived here yet!

Woe, what a black hour it was!To hell with the plane that brought us here! [Black Panther p.132]

As David Hirst, formerly the Guardian’s Middle East correspondent wrote: ‘Nothing the rulers of Israel could do quelled the bitterness which the newcomers nurtured against them. They were lectured, in their transit camps, by teams of Zionist educators. But, long after they left the camps, they continued to sing that song, even at weddings and festive occasions. It remained popular throughout the fifties. Then it eventually disappeared, but it can hardly be said that nostalgia for the ‘old country’ disappeared with it. For the contrast between what they once were, ‘in exile’, and what they became, and remain, in the Promised Land is too great. One of the ‘most splendid and rich communities was destroyed, its members reduced to indigents’; a community that ‘ruled over most of the resources of Iraq… was turned into a ruled group, discriminated against and oppressed in every aspect’. A community that prided itself on its scholarship subsequently produced fewer academics, in Israeli universities, than it brought with it from Iraq. A community sure of its own moral values and cultural integrity became in Israel a breeding ground ‘for delinquents of all kinds’. A community which ‘used to produce splendid sons could raise only “handicapped” sons in Israel’. [Black Panther, p.133, David Hirst, p. 291.]

In 1977 the Oriental Jews of Israel gained their revenge on the Israeli Labour Party when they put Menachem Begin of Likud in power. In the early fifties the need for immigrants was such that a columnist in Davar, paper of Histadrut, wrote:

‘I shall not be ashamed to confess that if I had the power, as I have the will, I would select a score of efficient young men – intelligent, decent, devoted to our ideal and burning with the desire to help redeem Jews—and I would send them to the countries where Jews are absorbed in sinful self-satisfaction. The task of these young men would be to disguise themselves as non-Jews, and plague Jews with anti-Semitic slogans such as ‘Bloody Jew’, ‘Jews go to Palestine’ and similar intimacies. I can vouch that the results in terms of a considerable immigration to Israel from these countries would be ten thousand times larger than the results brought by thousands of emissaries who have been preaching for decades to deaf ears.’ [Uri Harari, cited in Alfred Lillienthall, The Other Side of the Coin, Devin-Adair, New York, p. 47.]

‘CRUEL ZIONISM’—OR THE ‘INGATHERING’ OF IRAQI JEWRY

Shortly before Passover, it was announced that Jews wishing to leave the country should register at the Central Synagogue in Baghdad, but the Jews felt that this might be a trap to round up suspected Zionists and only four thousand registered. [Schectmann, p.111]

On 19 March 1950 a bomb exploded at the American Cultural Centre in Baghdad which was a favourite meeting-place for young Jews. There were some casualties then, but no one was injured in the later bomb explosions which occurred at two Jewish concerns, the Betlawi Automobile Company on 10 May and the Stanley Shasha Trading Company on 5th June.

On 8 April 1950, the last day of Passover the Jews of Baghdad were strolling, as was their custom, along Abu Nawas Street beside the River Tigris, which is flanked by public gardens on the river’s edge and buildings on the other side. The Dar al-Beida coffee-house was very popular with young Jewish intellectuals who, on warm evenings would sit at tables in the garden in front of the cafe, under strings of coloured lights, sipping Turkish coffee and soft drinks.

At half-past nine, a bomb exploded near the Dar al-Beida and four people were seriously injured. Abd al-Jabbar Fahmi, Baghdad’s chief of police, and his men spent several hours interviewing those who had been in the café and, the following day, it was reported that the police had announced that the bomb had been thrown from the neighbouring Al Hanna restaurant and bar. The report added that some arrests had been made. [Al Zaman, Iraqi newspaper, 10.4.50.]

The Jewish Chronicle reported that: ‘Four Jews were seriously injured in Baghdad recently when a bomb was thrown into a crowded cafe frequented by Jews.’ [19.5.50.] The police later announced that three Jews had been arrested in connection with the incident. The day after the explosion, many Jews flocked into the offices which had been set aside for those who wished to renounce their citizenship and to apply for permission to leave for Israel. Most of them were poor Jews who had nothing to lose. Many of them recalled the riots of 1941. About 10,000 Jews signed up to leave after the bomb; the big Ezra Daud synagogue had to be set aside as a registration office. Soon however numbers tapered off.

The third time there were victims. It happened outside the Mas’uda Shemtov synagogue. The synagogue was full of Kurdish Jews from the northern city of Suleimaniyyah. On 14 January 1951, a bomb exploded. Ekhak Salman, a seven-year-old Jewish boy, was killed, and twenty-seven Jews were injured (two of them eventually died). An Iraqi newspaper asked: ‘Are there some Jews behind the incident?‘ [Lwa al-Istiqlal, 15.1.51.] and it went on to report that, two minutes after the explosion which blew a large crater in the ground between the two doors of the synagogue, a taxi had driven away from the building, carrying some Jewish passengers on their way to the airport. The bomb was reported to be of British manufacture.

After the first bomb was thrown at the Dar al-Bayda coffee-house, many rumours started running around about those responsible being communists. But the day after the explosion, at 4.00 AM, leaflets were already being distributed amongst the first worshippers at the synagogue. The leaflets warned of the dangers revealed by the throwing of the bomb and recommended the people to come to Israel.

Salman al-Bayyati, the Investigating Judge for South Baghdad, declared that the distribution of the leaflet at such an early hour showed prior knowledge of the bombing. He instructed the police to follow this line of inquiry, determining at the same time that those who threw the bomb were Jews trying to quicken the emigration. Indeed, two youngsters of the Muallim family were arrested.

Then the Ministry of Justice intervened. The two boys were set free and the case was transferred to the examining magistrate of north Baghdad, Kamal Shahin. At this stage, there was still a willingness not to see. An Iraqi lawyer, who lived in Southern Tel Aviv added that, at that stage, it was considered justifiable to turn a blind eye because of an active agreement between the government and the Zionist representatives. But after two more bombs and after the arrest of the Israeli envoy the police were forced to act. In the objective conditions of the issue, the trial was held according to international law. The evidence was just such that it wasn’t difficult at all to pronounce such sentences. [Woolfson pp. 193-4 citing Black Panther (Hebrew) 9.11.72., Documents From Israel, Ithaca Press, 1975, pp. 130-2, Haolem Hazeh, 20.4.66. and 29.5.66.].

Dr Schechtman wrote that in January 1951 ‘a series of bomb outrages causing several deaths and scores of wounded precipitated a virtual stampede. Between 14 January and 10 March, forty thousand registered, over twenty thousand per month.‘ Each applicant was required to sign the following statement:

I declare willingly and voluntarily that I have decided to leave Iraq permanently and that I am aware this statement of mine will have the effect of depriving me of Iraqi nationality and of causing my deportation from Iraq and of preventing me forever afterward from returning. [Schectmann, p.112]

When the registers were completed, it was found that all the Jews of Iraq, with the exception of some five thousand, had registered to emigrate to Israel. [Shechtman p.106] There was no longer any doubt in Jews’ minds that an anti-Semitic organization was plotting against them. The queues lengthened outside the Ezra Daud synagogue.

A few days later, the government, led by Nuri es-Said, went into secret session, following which the Majlis (legislative assembly) also went into secret session. It was proposed that the property of every Jew who had renounced his citizenship prior to departing Israel would should be confiscated. No one was allowed to take more than £70 out of the country.

All those who had not given up their citizenship had to present themselves at special registration offices to be provided with new identification certificates. They would continue to be regarded as citizens with equal rights and they could have passports and travel abroad, but they had to return to Iraq within three months or they would lose their citizenship. The five thousand Jews who remained were permitted to carry on their businesses without any restrictions.

Suddenly, one of the richest and most splendid Jewish communities in the world had lost everything. The rapid and total destruction of an ancient and cultured Jewish community had taken place. [Haolem Hazeh, 20.4.66.] In Israel, its members became paupers, and from a highly educated group with a very large proportion of university graduates, it was reduced to one that was poorly educated, oppressed and discriminated against in every way. [Black Panther, 9.11.72.] But they soon learned that the explosions were the work not of Arabs but those who sought to ‘rescue’ them.

The subject of the Baghdad bombs and the question of who was responsible for them would probably not have arisen years after the event if it had not been for the Israeli government’s habit of constantly reminding the country’s Jewish inhabitants of the past sufferings of the Jews. When it comes to European Jews there is ample material concerning past persecutions, but, with those from Arab countries, it is a little more difficult. Victor Halba described how he had gone to Kiryat-Gat in connection with his work and found that a stage had been erected in the town’s central square for the forthcoming Israeli Independence Day celebrations. Across the whole length of the stage was a placard with a list of all the terrible names which were so familiar to people in Israel: Auschwitz, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, etc. At the end of the macabre list, he wrote, there was a name which he had never heard before and which did not seem to fit into the list. He asked a friend who lived in the area what the name signified and he was told that a large number of the town’s population were of North African origin. The commemoration of the Holocaust, therefore, conveyed little to them, and so the organizers of the ceremony had tried to find some area of Jewish suffering with which they could identify and had got hold of the name of a site in Tunisia where the Nazis had started to build a concentration camp during the short time that they were in control there.

Needless to say, this gesture was unsuccessful as hardly any of the town’s residents had ever heard the name of the site and even the few who recalled its significance were unmoved by it. [Woolfson pp. 189-90, Haolem Hazeh, 28.9.76.]

It was because of a stone memorial, built in 1966 in Or Yehuda, the place where thousands of Iraqi Jewish immigrants live in Israel, that the events of 1950 and 1951 were re-examined. The memorial was erected in memory of two Baghdad Jews ‘who were hanged for their part in the unfortunate Iraqi affair after their trial according to the principles of international law.’ This account, in Haolam Hazeh, described how: ‘Twenty-five years ago, there were whispers about “Cruel Zionism” but only now is the most secret affair in the history of the State of Israel revealed.‘

Under the heading of ‘Self-defence against persecution’, the Encyclopedia Judaica explains that: ‘The Iraqi authorities contended that the bombs were planted by Jews, to humiliate Iraq in the eyes of the world. In June 1951 several dozen Jews were arrested, a few of whom were accused of planting bombs. In December 1951 two of them, a lawyer, Joseph Basri, and a shoemaker, Abraham Salih, were condemned to death. They were hanged publicly in January 1952. These two young men had been active in the clandestine Zionist organization Hehalutz, established in 1942. … About six hundred members of the Haganah were instructed in the use of weapons in Baghdad, Basra, and Kirkuk. In 1949-50 the Haganah helped to organise the illegal exodus to Israel, and in 1951 it was decided to hide the arms. In this last activity Basri and Salih were caught, together with dozens of other members of the Haganah.’ [Encyclopedia Judaica, Keter Publishing House, Jerusalem, 1971, Vol. VIII, cols 1453-4.

There was no doubt about the guilt of those convicted, despite the World Jewish Congress writing ro the Foreign Office stating that ‘Muslim brothers must be responsible.’ On 31.1.51. the Foreign Office wrote to Sir Anthony Nutting, the Foreign Office Minister inquiring into the affair (Nutting was later to resign over the invasion of Suez and Sir Anthony Eden’s duplicity in 1956]. The FO told Nutting that they had no indication that the trials were improperly conducted. [P.A. Rhodes for the FO, FO 371/48767, EQ 1571/2]. This was later endorsed by Wilbur Grane Eveland, former CIA adviser in Baghdad at the time. [Shiblak, pp. 153-4]

It was a combination of circumstances at the time of the unveiling of the memorial which led to many disclosures about the past being made by those who felt, perhaps, that they had remained silent for long enough. The Israel magazine Haolem Hazeh, published by Uri Avnery who was then a member of the Knesset, wrote that it had decided to tell the story because all those who had been involved in the events in Iraq, with the exception of the two who had been hanged, were in Israel.

Part of the article was later reprinted in Black Panther [9.11.72] and also in Middle East International. [January 1973] The only inaccuracies in the article concerned the number of casualties.

According to Haolam: ‘On one point, all the immigrants who followed the “Iraqi Affair” closely, or were involved in it, including the families of those who were hanged . . . were agreed that they praised Haolam Hazeh for its decision to expose the secret. “The time has come,” they said, “for the people of Israel to know what efforts were made to bring the Jews of Iraq to Israel and what they left behind them.” ‘ Haolam Hazeh made it clear that its informants were those who had been involved in the events in Baghdad, and it seems fairly obvious that if they were responsible for the bombs, they were not prepared to admit that they had deliberately caused more than the minimal number of casualties.

One of those involved who had decided to unburden himself was Yehuda Tajar, an official of the Israeli Foreign Ministry who eventually became an attaché at the Israeli Embassy in London. He was a Zionist agent in Haganah, who was sent to Baghdad from Israel in 1950 on what he described as ‘a national mission’. He was caught out by a Palestinian Arab who served the coffee in the office of the military police in Acre, where Tajar had been an officer.

This Palestinian ended up in Iraq and in the summer of 1950, Tajar entered Uruzdi Beg, the largest general store in Baghdad. The salesmen, a Palestinian refugee who had been the coffee-boy in Acre recognised Tajar. He ran into the street, where he told two policemen. Tajar, who admitted to the police that he was an Israeli, explained that he had gone to Baghdad to marry a young Iraqi Jewish girl. Kadouri Eluyah, [a former member of the local council of Or Yehuda] was quoted as saying that the many Jewish salesmen who worked in the store succeeded in confusing the Palestinian in order to give Tajar a chance to escape but that Tajar went back the following week and it was then that the refugee ran outside and Tajar was arrested. Ben Porat was arrested too, but he succeeded in convincing the police that he did not know Tajar and he was released on bail of two thousand dinars. He jumped bail and left for Israel.’

Salih, a young native of Baghdad who was in charge of the Haganah arms caches. He broke down under questioning and took the police from one synagogue to another, showing them how he had hidden his weapons. [Haolem Hazeh, 20.4.66.]

Tajjar’s revelations led to more arrests, some fifteen in all. During the trial, the prosecution charged that the accused were members of the Zionist underground. Their primary aim – to which the throwing of the three bombs had so devastatingly contributed— was to frighten the Jews into emigrating as soon as possible. Two were sentenced to death, the rest to long prison terms.

It was Tajjar who first broke Jewish silence about this affair. Released after ten years, he told all to Haolem Hazeh, the weekly magazine edited by Uri Avneri. On 29 May 1966 Ha’olam Hazeh published an account of the emigration of Iraqi Jews based on Tajjar’s testimony. On 9 November 1972, Black Panther, militant voice of Israel’s Oriental Jews, published the full story.

Also arrested was Mouzad Kazzaz, who was later to become a member of the Knesset under the name Mordechai ben Porat. He was known to other members of the under ground as ‘Zaki’ and he served as the local commander of the underground. Haolam Hazeh referred to Yehuda Tajar as ‘the big fish’ in the affair and, indeed, as Ben Porat pointed out later: ‘For the police, I was no more than a poor idiot of a local Jew. They were interested in the big catch, in the Israeli Tajar.’ [Jeune Afrique, 22.2.78.]

A few weeks after its previous story, Haolam Hazeh published more revelations. This later account mentioned that the President of the State of Israel was to take part in the unveiling of the memorial at Or Yehuda and added: ‘Zionists in Iraq have suddenly become famous. Those who led the underground now hold different posts in Israel, and they have begun to recall the past. . . . Basically, their movement was no different from its counterparts in other Arab countries. It was given a push by the Second World War: Europe went up in flames and the Jewish population in Palestine was cut off from its roots there. For this reason, the Zionist movement turned towards other sources, nearer ones…’

Envoys of the Jewish Agency and Haganah arrived in Iraq with forged documents of British soldiers and assimilated themselves among the local Jews. The envoys were helped by bonafide Jewish soldiers who assisted them to set up the first arms caches of Haganah in Iraq.

The account revealed that Ben Porat had blamed Tajar for the arrests as the Iraqi detectives found in the pocket of the Israeli agent a notebook in which were written the telephone numbers of all the members of the network.

Referring to what it described as ‘cruel Zionism’ (deliberately simulating anti-Jewish manifestations), the article explained that a number of Iraqi lawyers who followed the military trial which sentenced Salih and Basri to be hanged and Yehuda Tajar to life imprisonment (he was released after 10 years) agreed that the conclusion of the trial had been correct and the bombs were thrown by the underground. Mordechai ben Porat, however, disagreed and claimed that anti-Jewish elements in Baghdad had thrown the bombs.

One man who challenged Porat’s version and who wrote to Israel’s Prime Minister and the Minister of Justice, demanding that an enquiry should be held into the whole matter, expressed the hope that Ben Porat would prosecute him so as to bring certain facts to light but Ben Porat commented: ‘I would not prosecute such small fry.’

Other facts have been revealed. For example an Iraqi Jew who went to Israel in 1951 described how a poor Baghdad shoe maker left his job and was seen ‘living, the life of a pasha, dressed in new clothes’, in 1950. It became known among the Jews in Baghdad that the shoemaker had been approached by the Zionist underground and had been given one hundred and fifty dinars ‘to perform a simple task’. He was asked in travel to Zakhou in the north of Iraq, dressed as a Muslim Arab and, on the Sabbath, when Rabbi Nahum and the congregaton emerged from the synagogue after the service, he was instructed to approach the rabbi, spit in his face and strike him. He did these things and, when the Jews saw them, they became afraid that they were going to be attacked and persecuted. Eventually, because of such incidents (we are told that there were probably many similar ones) and because of the bomb explosions, all the Jews left Zakhou. [memorandum from Eliahu Yusef to Marion Woolfson, 12.12.77., p. 195]

Mr Reuben Naji Elias, a cinema and property-owner and President of the Baghdad Jewish community, and Mr Naji Chachak, a lawyer, who was Secretary of the community, both said that there was no doubt in their minds that the bombs were the work of the Zionist underground. [testimony to Marion Woolfson 12.12.77.]

An Iraqi Jew, a member of the communist party and who was imprisoned from 1949 until 1958 and then from 1959 until 1961, outlined his story:

‘I joined the communist party, as many young people, both Jewish and Muslim, did because of the exploitation we had suffered. I was not a Zionist and had no wish to go to Israel. The prison in which I served my sentence was built by the Americans, especially for communists and other political prisoners, and the Americans used to visit the prison and complain if we were not being treated harshly enough. …. While I was in prison, members of the Zionist underground were brought in to serve their sentences and they used to talk quite openly about their exploits. They spoke about a British man in Baghdad who was known as ‘Mr Rodney’; he was a notorious fascist … He ran a brothel in Baghdad which was called the Red Palace and this house was used for meetings between the Zionists and Iraqi leaders. ….

The Zionist prisoners told me that their instructions had been that, if it was necessary, they could kill up to twenty per cent of the Jews of Iraq in order to send the remainder to Israel. When I was released from prison, …. I went to Israel because my wife was there and, anyway, I had no money. Some of my relatives are still in Israel, but I never want to go back. [He left for good in the 1960s.] [Memorandum from Ezra Cohen to Marion Woolfson 5.6.78., Prophets in Babylon, p. 196]

After the revolution of 1958 in Iraq, the former head of the government, Tawfiq as-Suaidi, was put on trial for treason, and one of the clauses in the indictment was that he had aided Israel ‘by allowing one hundred thousand Iraqis to become Israeli citizens’. [Haolem Hazeh 20.4.66.]

The exodus of the Iraqi Jews to Israel was described in the introduction to an article headed ‘Give us the bodies of the Jews and take their possessions‘, by Shalom Cohen, an Iraqi-born Jew and a former member of the Knesset, and it was explained that the bomb outrages were clearly brought to mind twenty-five years later through legal proceedings concerning the conflict between two men, both of them Israelis, Baruch Nadel and Mordechai Ben Porat. Nadel was a journalist, well-known for his investigative work in the spheres of corruption in Israel and ‘’He is also known for having denounced the discrimination and exploitation of the oriental Jews in Israel . . Baruch Nadel is the author of a document which specifically accuses the Israeli establishment of having deliberately perpetrated the outrages in Baghdad.’

Born in Baghdad fifty-four years ago, Mordechai ben Porat joined the Israeli army in 1945 and had taken part, as an officer in the conflict which followed the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. He was until May 1977, a Labour/Rafi member and Vice-President of the Knesset. He was accused by Baruch Nadel of participating in the activities of a group of politicians who ‘had succeeded in imposing themselves on the Jewish people by a thirst for power’.

From October 1977 until January 1978 he was sent by the Israeli Foreign Ministry on a mission to the United States, in an endeavour to convince responsible American politicians and the foreign representatives of the United Nations that the same international status should be accorded to the organisation over which he presides (the World Organisation of Jews from Arab Countries) as that which is received by Palestinian organizations. On his return to Israel at the end of January, he wrote to the Prime Minister, Menachem Begin, to demand the right to participate in the peace negotiations with Egypt.

But first, he made his way to the law courts in Tel Aviv where proceedings for defamation which he had raised against Baruch Nadel were taking place.

The article stated that it was going to reveal the preliminary results of the enquiry of Baruch Nadel and the first disclosures made at the court hearing, and that Shalom Cohen, correspondent in Israel of the Parisian daily newspaper, Le Matin, had devoted himself to the rights of non-European Jews in Israel and was also militating for the recognition of the rights of the Palestinians. But this did not prevent him from declaring himself to be a Zionist and, according to the magazine’s editors, it was that which made his article so valuable.

He wrote that a scandal which had shaken the Israeli public for nearly a year had been caused by an article written by Baruch Nadel and first published in the journal of the Sephardic or Oriental Jewish community in Jerusalem. This article dealt with the ‘forced’ exodus of the Iraqi Jews who were, in fact, driven to emigrate to Israel in the 19503 by terrorist measures for which those responsible were Israelis. A passage of the text which triggered off the outcry indicates the tone of the piece:

‘Zionism,’ wrote Baruch Nadel, ‘not having saved the Jews of Europe found itself after the Second World War without a useful objective. To give a moral justification to the existence of their country, the Zionists looked for a way to “save” other Jews in spite of themselves. The only Jews with whom this would be possible were those of the Arab world.’

The author asserted that David Ben Gurion and his men arrived at an agreement with the Imam Yahya of Yemen, Nuri es-Said of Iraq, and other Arab rulers. The agreement, said Nadel, was simple. The Zionists told the Arabs to take the possessions of the Jews in return for allowing them to emigrate to Israel, but, in Iraq, this agreement met with difficulties because the Jews who lived in prosperity had no wish to emigrate. The official Israeli emissaries then threw bombs in Jewish areas, causing panic and forcing practically all the Jews of Iraq to leave for Israel in less than a year. [Jeune Afrique 22.2.75.]

Naeim Giladi in his book Ben Gurion’s Scandals: How the Haganah & the Mossad Eliminated Jews, says

“On November 9, 1972, the Panthers’ official organ,

The Black Panther, [this is referring to the Israeli, not American

organization a report under the byline of Koshavi Shemesh, which was a

complete reprint of what Ha’olam Haze had reported in June-April 1966.

We had hoped that Ben-Porat would sue us, and through trial, we expected

that the truth behind the bombings of Baghdad would be told — that the

responses to hundreds of questions would be finally given. Shalom Cohen

who was Knesset member at that time had even prepared the ground for an

eventual lawsuit. But to out regret, neither Ben-Porat, nor Ben-Gurion

sued us.” [pp. 277 – 278]

On page 314, Giladi interviewed Wilbur Crane Eveland, former advisor to the CIA, who wrote the book Ropes of Sand, where he discusses Zionist Jews planting bombs in Baghdad.

Mordechai Ben Porat was quoted as saying: ‘All those who know me and who know that I was sent by Israel to Iraq during this period hold me responsible for bombs thrown at this time. This is an untrue accusation, totally without foundation.‘ Shalom Cohen commented that this was the argument put forward by the plaintiff but, he asked, what was the reality? He described the events which had taken place in Baghdad before and after the bomb explosions and then he reported a clandestine radio message sent to Israel which said: “The situation of the Jews is very bad. They have lost their nationality. They have left their homes and their jobs. Why did you force us to lie to them and to promise them unlimited immigration?’

In the maabaroth, [transit camps in Israel] rumours on the subject of the bombs in Baghdad kept circulating. After all, it was pointed out, the Iraqi court itself had found the Zionist organisation guilty of these acts, and also, when some years later there burst on Israel the scandal of the revelations concerning the activities of a net which had planted bombs in Alexandria and Cairo, the Israeli Defence Minister himself remarked: ‘This method of operation was not invented for Egypt. It was first tried in Iraq’, and other Israeli leaders saw in these outrages acts of ‘cruel Zionism’. The term is attributed to David Ben Gurion concerning anti-Jewish acts carried out by the Zionist movement to force certain Jewish communities to emigrate to Israel ‘in their own interest’.

Israeli law allows someone accused of libel to submit to his accuser a list of questions to which he must reply, so Nadel took three months off work from his newspaper to research the documents which supported his accusations. As a result, three hundred and sixty-five questions were presented to the court. Among them was one which asked Ben Porat whether it was true that, when he was nominated for the presidency of the local council of Or Yehuda, people called after him in the streets and treated him with hostility because they considered the Zionist underground to be responsible for the bombs in Baghdad.

He was also asked whether he knew that Mr Avraham Dar, the agent of Mossad (the Israeli Secret Service) who had formed the network which was responsible for acts of sabotage in Egypt happened to be on a mission to Baghdad shortly before the bombs were thrown. Another question was whether he was aware that, shortly after the bomb explosions in Baghdad, other bombs were thrown in Morocco by Israeli emissaries and by militant local Jews in the areas of densest Jewish population and that, during the same year of 1951, Israeli agents were delivering to the homes of Jews in Morocco pamphlets which advised them to send their children to Israel so that they could take refuge from future outrages. A further question concerned the fact that the select group of agents who were concerned with the falsification, in Baghdad, of documents for illegal emigration, had specifically named the member of the Zionist underground who had, they claimed, thrown the grenade.

The Zionists now claim they are vindicated because Nadel didn’t

pursue his defamation case. But in fact he was unable to do so because

biased judges and judicial system invalidated many of his questions and preferred, as is

usually the case in Israel, not to have any definitive verdict on an

unsavoury episode in Zionist history. Giladi writes:

Mordechai Ben-Porat finally made a mistake in August 1977,

when he hired attorney Micha Caspi and sued Baruch Nadel for libel. He

requested half a million Israeli pounds in damages. In such cases,

there is a provision in Israeli law under which the defendant may submit

a number of questions to the plaintiff. The case went before Judge

Zamir. Nadel submitted 365 questions. When Ben-Porat read the

quetions, he was so outraged, he complained they were humiliating and

insulting. On February 6, 1978, during the court proceedings the judge

invalidated many of the questions. Later, the case was transferred to

Judge Ben-Dor who invited the opposing counsels. On July 8, 1079, he

proposed the following compromise:1. Baruch Nadel did not have the entire facts straight when he gave the

interview

2. The Babylonian (Iraqi Jewry) was praised for immigrating to Israel

out of love for it and for Zionism.

3. The work done by Israeli immigration agents in Iraq was outstanding.It is worth noting that Baruch Nadel (formerly known as Baruch Oren) was

about to immigrate to the United States, and would have been unable to

leave Israel while the case was pending. This put him as well as the

editors of Yediot Aharonot under pressure. He ended up

accepting the compromise proposed by Judge Ben-Dor. Unfortunately the

deal did not allow Nadel’s report, arguments or accusations to be

discussed.

.

.

.

In its issue of November 23, 1983, Ha’alam Haze printed again

the past reports on the Baghdad bombings to counterbalance Ben-Porat’s

statements on television. Knesset member, former General Mattityahu

(Matti) Peled called for an investigation.In a letter to the editor of Ha’aretz (November 25, 1983) and in

response to Peled’s initiative, Ben-Porat made a promise. He promised

that Peled’s grievances would be addressed at a forthcoming meeting to

be held on December 8, 1983, in honor of all those who ran the illegal

immigration network in Iraq. Many people went to the meeting hoping to

hear the answers to Peled’s questions, but Ben-Porat talked about

everything except the bombings (Ha’olam Haze, December 14, 1983) (page 279, Ben Gurion’s Scandals: How the Haganah & the Mossad Eliminated Jews).

Mr Amnon Sayegh, who had been under Ben Porat’s orders in Baghdad, made the following deposition: ‘The explosions accelerated the emigration. Those who were hesitant decided to leave their country and those who had had no thought whatever of emigration began to think about it. It could have been that the bombs were thrown in order that the government in Israel would realize the gravity of the situation and take some action.’ The question was asked whether the facts and conclusions set out in this deposition were true, while a final query was: ‘Is it true that, before the explosions, the Zionist underground paid the journal of the Istiqlal Party, al-Yaqza, to publish articles against the Jews and to drive the Jews to leave their country?’

Shalom Cohen claimed that WOJAC (the World Organization of Jews from Arab Countries), ‘manipulated by Moshe Dayan, to counter the claims of the Palestinians, could only be successful if international public opinion admitted his basic premise, that Jews we’re kicked out of the Arab countries and had, in consequence, the right to claim the status of refugees.’ ‘Ben Gurion,’ wrote Baruch Nadel, ‘founded his entire political career on an everlasting war against the Arabs, and all Israeli governments have succeeded him in not wishing peace.’ [Jeune Afrique]

An interesting insight into Zionist beliefs is provided by the following passage in Shalom Cohen’s article: ‘We must admit that we do not see in the act itself [the throwing of the bombs] an absolute evil. In our opinion, it is allowed, in special circumstances, to lead people towards national liberation and to personal safety against their wishes as did Lehi [the Stern Gang] during the fight against the British in Palestine.’ [Jeune Afrique 22.2.75.]

The Black Panther account includes the testimony of two Israeli citizens who were in Baghdad at the time. The first, Kaduri Salim

‘… is 49 but looks 60. … he lost his right eye at the door of the Mas’uda Shemtov synagogue. ‘I was standing there beside the synagogue door. I had already waived my Iraqi citizenship… Suddenly, I heard a sound like a gun report. Then a terrible noise. I felt a blow, as if a wall had fallen on me. Everything went black around me. I felt something cold running down my cheek, I touched it—it was blood. The right eye. I closed my left eye and didn’t see a thing. The doctor told me: ‘It’s better to take it out.’

When he arrived in Israel, the former clerk was sent to an immigration camp. Since then, all his efforts to receive compensations have been in vain. ‘I was hurt by the bomb. The Court of Law established that the bomb was thrown by “The Movement”. The Israel Government has to give me compensation.’ But the Israel Government does not recognize its responsibility for the Baghdad bombs and, anyhow, cannot recognize him as hurt in action. ‘I am ready to be a victim for the State,’ he said, ‘but when the situation at home is bad, when my wife wants money and there isn’t any, what is the self-sacrifice and goodwill worth?’

By the end of Israel’s ‘War of Independence’, there were still 130,000 Jews in Iraq. As the Chief Rabbi of Iraq, Sassoon Khedduri, explained a few years later:

‘The Jews – and the Muslims – in Iraq just took it for granted that Judaism is a religion and Iraqi Jews are Iraqis. The Palestine problem was remote and there was no question about the Jews of Iraq following the Arab position.’ [Rabbi Elmer Berger, Who Knows Must Say So, Institute for Palestinian Studies, Beirut, p.30]

There is also a very interesting review by Rayyan Al-Shawaf of Abbas Shiblak’s book Iraqi Jews: A History of Mass Exodus (Saqi, 2005, 215 pp.). See also Naeim GILADI BEN-GURION’S SCANDALS Part 4

What is most noteworthy however, as Tom Segev recognised in ‘1949: The First Israelis’ ‘It is significant the rumor arose at all, and that it was persistently

repeated, even by Iraqi Jews. Obviously the idea was not unthinkable.’

Tony Greenstein

Iraqi Jews reject ‘cynical manipulation’ of their history by Israel, Zionists, writer Almog Behar tells EI

Submitted by Ali Abunimah on Mon, 09/17/2012 – 09:04

Yacoub Youssef, an Iraqi Jew, holds his prayer book in his house in Baghdad’s Tanaouine neighborhood, 19 April 2003.

(Awad Awad / AFP/Newscom)

“It is far from the first instance of tampering with, exploiting, and deleting our history, but it is the straw that broke the camel’s back, and so … we formed the Committee of Baghdadi Jews in Ramat-Gan.”

This is how writer, poet and activist Almog Behar described a decision by a group of Jews from Arab and Kurdish backgrounds to speak out forcefully against renewed Israeli government propaganda efforts to counter Palestinian refugee rights by using the claims of Jews who left Arab countries for Israel in the 1950s.

Israeli diplomats, Haaretz reported last week, “have been instructed to raise the issue of Jewish refugees from Arab countries at every relevant forum. This is part of a new international campaign to create parity between the plight of Jewish and Palestinian refugees, Deputy Foreign Minister Daniel Ayalon announced on Monday.”

“The way the Israeli establishment uses our history from the 1950s, is not in order to give us our rights back, but in order to get rid of the rights of the Palestinians, and avoiding a peace agreement with them,” Behar wrote to The Electronic Intifada.

The idea is that Palestinian refugee and property rights are negated by equivalent claims from Jews from Arab countries, thus absolving Israel of having to make any restitution to Palestinians. Jews who left Iraq and some other Arab countries in the 1950s for Israel were deprived of their property and citizenship.

The Israeli government does “not represent us”

But in an extraordinary statement posted on Facebook last week, the newly-formed Committee of Baghdadi Jews in Ramat-Gan, of which Behar is a founding member, hit back:

We are seeking to demand compensation for our lost property and assets from the Iraqi government – NOT from the Palestinian Authority – and we will not agree with the option that compensation for our property be offset by compensation for the lost property of others (meaning, Palestinian refugees) or that said compensation be transferred to bodies that do not represent us (meaning, the Israeli government).

The statement went on to demand an investigation of Israel’s complicity in the departure of Iraqi Jews from their homeland including in terrorist acts against Jews:

We demand the establishment of an investigative committee to examine:

1) If and by what means negotiations were carried out in 1950 between Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri as-Said, and if Ben-Gurion informed as-Said that he is authorized to take possession of the property and assets of Iraqi Jewry if he agreed to send them to Israel;

2) who ordered the bombing of the Masouda Shem-Tov synagogue in Baghdad, and if the Israeli Mossad and/or its operatives were involved. If it is determined that Ben-Gurion did, in fact, carry out negotiations over the fate of Iraqi Jewish property and assets in 1950, and directed the Mossad to bomb the community’s synagogue in order to hasten our flight from Iraq, we will file a suit in an international court demanding half of the sum total of compensation for our refugee status from the Iraqi government and half from the Israeli government.

Zionist role in flight of Jews from Iraq

The role of Israel and Zionist undercover agents in helping precipitate the departure of Jews from Iraq has long been suspected.

Naiem Giladi, an Iraqi Jew who joined the Zionist underground as a young man in Iraq and later came to regret his role in fostering the departure of some 125,000 Jews from Iraq, wrote that, “Zionist propagandists still maintain that the bombs in Iraq were set off by anti-Jewish Iraqis who wanted Jews out of their country.” But “the terrible truth,” Giladi said, “is that the grenades that killed and maimed Iraqi Jews and damaged their property were thrown by Zionist Jews.”

Giladi, who was born Naeim Khalaschi, gave his account in an article published by Americans for Middle East Understanding in 1998 which summarizes his book, Ben Gurion’s Scandals: How the Haganah and the Mossad eliminated Jews.

After being sentenced to death in Iraq for his Zionist activities, Giladi fled to Israel. Because his native language was Arabic, Giladi was assigned to assist the Israeli military occupation authorities expel Palestinians from their homes in al-Majdal (“Ashkelon”) by pressuring them to sign documents stating they were leaving to Gaza willingly:

I was there and heard their grief. “Our hearts are in pain when we look at the orange trees that we planted with our own hands. Please let us go, let us give water to those trees. God will not be pleased with us if we leave His trees untended.” I asked the Military Governor to give them relief, but he said, “No, we want them to leave.”

I could no longer be part of this oppression and I left. Those Palestinians who didn’t sign up for transfers were taken by force—just put in trucks and dumped in Gaza.

Giladi, who died in 2010, served in the Israeli army from 1967-70, but then became active in the anti-Zionist Black Panther movement of Mizrahi Jews, and eventually abandoned Israeli citizenship and moved to the United States. He gave this hour-long interview in 1994.

Jews of Arab and Kurdish origin reclaim their history

I asked Behar by email to provide more background on the formation of the Committee of Baghdadi Jews in Ramat-Gan. Behar said he shared my questions with members of the committee and compiled and translated their answers.

Can you tell me more about the Ramat Gan Committee of Baghdadi Jews? When was it founded? Who does it involve?

The committee was founded because of the Deputy Foreign Minster’s refugee campaign, but it will deal with other issues. We decided to establish the Committee of Baghdadi Jews in Ramat-Gan following the attempt by the Deputy Foreign Minister and the Government of Israel to take advantage of our history in their cynical political manipulation.

It is far from the first instance of tampering with, exploiting, and deleting our history, but it is the straw that broke the camel’s back, and so yesterday morning we formed the Committee of Baghdadi Jews in Ramat-Gan.

The committee includes young and old, men and women, from Baghdad (and from Mosul and Basra), as well as some who were born in this country, in the first, second, and third generations, and those with mixed Kurdish and Moroccan ancestry.

We began the committee in order to reclaim our history and our culture (and of course our property), and to prevent others, including Zionist movements and the State of Israel, from possessing it for themselves.

So, we wrote our statement on September 14th in response to the government, and we will continue to be vigilant on a daily basis in the act of claiming our history. We believe that as a multigenerational Iraqi-Jewish community, we can write the story of our past, present, and future in Iraq and in Israel.

How widespread are the sentiments which the statement expresses?

We believe that those sentiments are very widespread among Iraqi Jews – of course more among the older generation, that is less affected by Israeli propaganda, and remembers more the Iraqi past – and knows that our property in Iraq is something between us and Iraq, and not between us and the Palestinians, and remembers also that most of Palestinian property from 1948 was taken by the Ashkenazim and the state, and not by Jews of the Arab world.

We believe that there should be a direct dialogue between Jews of the Arab world and the Arab states, and we hope that after a peace agreement the question of our property will be solved.

But the way the Israeli establishment uses our history from the 1950s, is not in order to give us our rights back, but in order to get rid of the rights of the Palestinians, and avoiding a peace agreement with them.

We do not want to be used, nor our history and personal stories to be used. We hope that the Arab world will understand that a dialouge with us, even before a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians, is important to it too. We are a part of Arab memory and history and culture, and it is wrong of the Arab world to forget our part in it, exactly as it was wrong of Israel to ask us to erase our Arabness or forget our past and language.

Were you aware of the account of Naeim Giladi?

We didn’t know Naeim Giladi’s work, but of course what happened in Iraq in the 1950s is an open wound for us, and we wish an investigation about the connections between Nuri as-Said and Ben-Gurion.

You can find out more about the Committee of Baghdadi Jews in Ramat-Gan on its Facebook page.

Comments

Jews from Tunis feel very much the same

Wed, 09/19/2012 – 08:42

The Jews of Tunis were subjected to a direct Nazi rule between November of 1942 and May of 1943. The state of Israel hasn’t to this day given our community any help in collecting the names of those who died in those terrible days or in getting proper compensation from Germany. Alone, a community of survivors is collecting names and has so far 670 names of our dead. And that is even before considering the pain and suffering caused when we were forced to leave Tunis with nothing.

My mother was 4 years old when she became a refugee. She lived in a tent with 9 other family members until that tent burnt down during a severe winter. The family was then given a hut and afterwards lived in a 30 square meter apartment. This poverty was the cause of being forced to leave with nothing. No money, no clothes, no chance of getting any real compensation for other goods – the house and so on. Israel was more interested in proclaiming my grandfathers Zionism then in helping him get justice from German and Tunisian authorities.

I therefore join the statements of the Iraqi Jews in saying that compensating us must be a separate issue from any negotiations with the Palestinians.

Tunisian Jews

Submitted by Deïr Yassin Thu, 09/20/2012 – 13:17

Sarit, you wrote “when we were forced to leave Tunis with nothing”.

Who forced you to leave and when?

The only time in history – a part from the Vichy-period – when Jews were obliged to leave Tunis was when the Touensa – the indigenous Tunisian Jews – asked the Bey of Tunis to expel the Granas, the Jews from Livorno, into the surburbs, if I recall correctly because of their ‘strange’ religious rituals (cf. Paul Sebag: Histoire des Juifs de Tunisie).

A documentary from France 5 (in French and Tunisian Arabic) on Tunisian Jews in France, with historians Lucette Valensi and Sonia Fellous.There is absolutely no record of Tunisian Jews being forced out of the country (the same is true for Morocco), the documentary presents many Jews saying that their Arab neighbours begged them to stay, many still have their Tunisian citizenship, their houses back in Tunisia and go there all the time. I don’t know enough about Zionist activity in Tunisia, but in Morocco, the Jewish Agency managed to convince people to leave without their full agreement.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJAY6DXzFGs

Submitted by Sarit Sat, 09/22/2012 – 19:46

I only know what my grandmother said once: A good Arab is a dead Arab. And she did not say it with any hate. She said it in great sadness. Because many Tunisians helped the Nazis to control, starve, rob and kill the Jews and after the Nazis were no longer there, still there was a lot of violence against us. A few Tunisians helped and they were afraid they will be punished for that and others said they would love to help but are afraid of what will be done to them.

After the Western powers left, the Arabs wanted to show the Jews again that they are considered low in the eyes of Muslims. Jews were beaten, robbed, women were raped and much more was done. 1941 in Iraq, 1945 in Lybia and smaller attacks daily in all the Muslim lands. No one would have gone if staying was an option. In all the Muslim lands life for the Jews became impossible. Many left when they could, others ran away later and for the most part – even if they could sell what was theirs – the price paid was nowhere near the real value.

My grandfather faced the option of staying in France but said that he had had enough of foreign rule and even if in Israel all he would get will be water and stale bread – that is the only place for him. He barely survived the Nazi times and the years after that were just as bitter. Not everybody shared his views – I have many relatives who live in France.

The Jews of Egypt were given a stamp in the passport saying they are not allowed to come back. I don’t know if my mother is welcome today in Tunis or if we will ever get our property back. Palestinian property is governed by an Israeli authority so that it or its worth can be given back in time.

Can Arab lands say the same about Jewish property taken, stolen or left behind?

I sometimes see Palestinian propaganda saying that all the Jews came to Israel from Europe and that they need to go back there. But I am half from Tunis and half from Romania – so where will they send me if they had the chance?