A Comparison by Simon Pirani formerly of the WRP

interesting article from a former member of the Workers Revolutionary Party

Central Committee, Simon Pirani, about the implosion of that group following

allegations of rape and sexual assault and violence against its founder, Gerry

Healy. However I would suggest that the

comparison with the SWP is limited. The

coup against Healy was an internal affair of the Central Committee itself at

first, whereas in the SWP it has been the members who have staged a revolt.

allegations against Healy were far more serious in that they involved multiple

rape and violence. But there are certain

parallels in the defences put up by Healy’s and Martin Smith’s [Comrade Delta]

supporters. The latter are asserting

that anyone who doesn’t support them and their revolutionary morality is a

political opponent.

Ken had been overcome with mid summer madness when he wrote it. But in fact Ken comes in a long line of social democrats such as the Webbs who apologised for Stalin’s terror.

|

| How Solidarity saw the fall-out |

Pirani. January 2013

controversy surrounding the Socialist Workers Party, and the way it has dealt

with accusations of rape and sexual harassment by a leading member, the

break-up of the Workers Revolutionary Party in 1985 has been referred to as a

worst-case scenario. Warnings have been issued that, if the SWP is not careful,

it will end up like the WRP. Such assertions imply that the WRP break-up was

essentially a bad thing. As one of many former WRP members active in labour and

social movements, I write

|

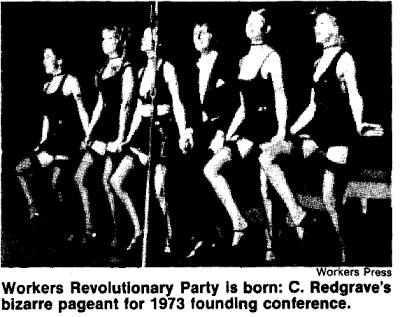

| The youth who Healy focussed on and whose political enthusiasm he destroyed |

overwhelmingly a good thing, and (ii) while there are great dissimilarities

between the two cases, there may be lessons of general relevance from 1985,

about “revolutionary morality” and forms of working-class organisation. Even at

this distance the break-up of the WRP is an emotional subject, for me at least,

and I don’t want to pretend – as people often do in discussions on the left –

to be rising “above” emotion or stating “objective” truths. This is just how I

see it. Given how hard-won our experience was, the least we can do is to try to

share it.

is worth repeating some key facts about the WRP break-up. It was triggered by

the expulsion of the group’s leader, Gerry Healy. He was charged with (a)

sexual abuse of women party members, (b) physical violence against party

members and (c) slandering David North, secretary of the US Workers League (a

sometime WRP affiliate) as “a CIA agent”. The sexual abuse by Healy was on a

completely different scale, and of a more extreme character, than the actions

reportedly complained of in the SWP. The letter from Healy’s secretary, Aileen

Jennings, that first raised the issue on the WRP’s leading committees, listed

26 alleged victims. This gave an indication of scale that justifies use of such

terms as “repeated” and “widespread”.

character of Healy’s offences is complex and worthy of proper analysis; any

attempt to summarise will be flawed. In a leaflet published in 1986, I wrote:

“A recent investigation by the WRP control commission, having taken written and

verbal statements, showed that Healy had systematically taken advantage of his

position of authority in the party to sexually abuse female comrades against

their will.” A redacted version of the control commission’s report appears in

the memoirs of my friend and comrade Norman Harding (who was a member of the

commission); these are published on line. None of Healy’s victims complained to

the police, and the old bastard died in 1989, without his crimes having been

properly measured against legal criteria.

1986-87, WRP members sought through discussion to understand more clearly the

power relations involved in Healy’s sexual abuse. One important theme was that

aspects of it were comparable to incest. Many years later, in 2011, I gave a

talk in which I tried to reflect this. I defined Healy’s abuses as “serial

rape, such as might be practiced on girls by their fathers or uncles, or in

institutions such as the Catholic church, and for which perpetrators might

expect long jail sentences in cases where they are caught and tried”. The

context was that the WRP in some ways resembled a religious sect, an issue I

also tried to tackle. (There is a list of links, including to sources

mentioned, below.)

constitution provided that, in the case of alleged disciplinary offences,

charges should be tabled, communicated to the member accused, and then heard by

a party body. The charges against Healy were tabled, appropriately, by the

central committee. Twenty-five CC members voted in favour of doing so; 11

against; Healy disappeared and did not turn up to the meeting. Some of his 11

supporters formed a faction. A week later, when the charges were heard, they

disappeared too; Healy was then expelled.

worth considering the grounds on which Healy’s supporters argued against the

charges being brought, despite the abundance of prima facie evidence.

Their knee-jerk reaction was to claim that Healy was the victim of a state

conspiracy. They have now had more than a quarter of a century to produce even

a sliver of evidence to back up that worthless nonsense, and have failed. More

important, to my mind, was their appeal to “revolutionary morality”, i.e. their

belief that, since Healy was a significant revolutionary leader, our morality –

as opposed to middle-class bourgeois morality – required that we defend him

from any and every attack.

abiding memories of 1985 is of a members’ meeting in Scotland, where I lived,

held in the week when Healy’s supporters comprised a faction, i.e. after the

charges had been tabled but before they had been heard. The meeting was

addressed by the late Corin Redgrave (brother of Vanessa), for the CC minority,

and myself for the CC majority. Redgrave opposed charging Healy, on the grounds

that it would damage the revolutionary leadership. In discussion, a veteran

member of the Scottish organisation asked Redgrave whether he could “look me in

the eye and tell me, honestly, that these charges are to your knowledge utterly

without foundation”, i.e. should not be brought because they were false.

Redgrave replied by citing the WRP’s achievements (publication of a daily

Trotskyist newspaper, building of a big youth movement, influence in trade

unions, etc) and concluded: “If this is the work of a rapist, let’s recruit

more rapists.” (In other words, he knew the charges had substance, but thought

they should be dropped because Healy’s “party building” achievements rendered

them irrelevant.) This statement deeply shocked those present, and we only

managed with some difficulty to continue the meeting in good order.

“revolutionary morality” existed only as Corin Redgrave’s depraved caricature,

it would be easy to dismiss. However there was a sense in which the pre-1985

WRP was held together by an apparently less crazy, less obscene (or perhaps

just less fully-developed) version of this “morality” – the sense that we were

a combat organisation, ordained by our ideology to bring certain truths to the

working class and replace its treacherous leadership with our own, and that we

had to do so on the basis of a set of moral precepts opposite to, and superior

to, those of capitalist society. Redgrave was actually taking to extremes a

position based on assumptions that I, certainly, had held for years.

best explain this in terms of my reaction to authoritarian and intimidating

behaviour by WRP “leaders”. Like almost all WRP members, I was completely

ignorant of Healy’s sexual abuse until the summer of 1985. (When I first heard

allegations of it, I tried desperately to put them out of my mind – a

complicated reaction I am happy to discuss, but won’t discuss here; once I

understood more, I strongly supported bringing the charges against Healy.) But

when it came to “leaders” bullying and demeaning militants, I could hardly have

remained in the organisation without accepting it and becoming used to it. A

good example of my “revolutionary morality” was my reaction to the bullying and

expulsion of a young militant – let’s call him C – whom I recruited to the WRP

in the late 1970s. In the mid 1980s, he had the temerity to express

disagreement with various things, including the WRP’s erratic – and at times

cowardly – attitude to the Irish Republican movement. At a CC meeting, Healy

shouted at C, slapped him on the face and kicked him. C was not being beaten

up; he was being humiliated by a very unfit man nearly three times his age. I

sat there with the other fit young members of the CC and said nothing. A few

months later C was beaten up, when, having been expelled, he tried to

enter a meeting to question leading WRP members openly. (I was not present.)

Although I had recruited C – and we were friends, inasmuch as there was such a

thing as friendship in our oh-so-hard combat organisation – I never once called

him up, or even enquired about why it had been necessary to expel him, or why

he had been beaten up. (Within weeks of Healy’s expulsion, I got back in touch

with C, and we remain friends to this day.)

|

| A dead reptile – Corin Redgrave covered up for Healy’s rape of young comrades on the grounds of revolutionary morality. Vanessa Regrave was and is equally culpable |

the sexual abuse, C’s humiliation and expulsion took place in broad daylight.

Many of us knew about it. In my view, our acceptance of such bullying in public

created the sort of organisation within which Healy felt the confidence to

practice serial sexual abuse in private. What explains that acceptance? My

memory long ago carefully blotted out details of the cowardice and indifference

with which I must have regarded C once he developed “differences”. But I know

how I would have justified it to myself, since I justified so many unpleasant

things in the same way: the party was the bearer of revolutionary tradition and

alone could open the revolutionary road to the working class; its leadership

was the vanguard, carrying out a historical mission; anything that obstructed

that leadership had to be swept aside. If C was not prepared to take his place

in this organisation, with all its imperfections, what use was he to the

struggle? And if he could not take his place in the struggle, what was the

point of worrying about him?

such logic to suppress my instinctive uneasiness about hierarchical and

bullying behaviour by senior party members. Having joined the WRP as an

energetic but impressionable teenager – the best type of recruit for any sect –

I soon learned to block off altogether any thoughts at all about authoritarian

forms of organisation, the WRP’s complete indifference to issues of the

oppression of women or gay rights, and many other things. The theoretical trick

played by the likes of Corin Redgrave to justify the WRP’s regime was that, as

revolutionaries, we based our behaviour on a set of moral considerations

“higher” than those of bourgeois society. Reference was made to Lev Trotsky’s

pamphlet Their Morals and Ours … although, on a close reading, even

there Redgrave’s position is demolished. Trotsky argues that the ends justify

the means, but cautions (a) that they do not justify all means, and (b)

that the ends themselves have to be justified. Clearly, Healy’s abuses could

only be justified in terms of “means” if one considered, as Redgrave did, that

the construction of the organisation was not a means, but an end in itself. In

the WRP’s case, once the construction of a “revolutionary” organisation,

separate from the wider movement, was made the end in itself, it increasingly

became the case that, in terms of means, “anything goes”.

say “separate from the wider movement”, this was not only in the sense of

having distinct ideas, but separate in many other ways. In this respect, too,

the WRP was an extreme example, with a staff of “professional revolutionaries”

who, through no fault of their own, had little connection either with the

workers’ movement or with student movements or other types of organisations.

The implications for the late 20th century of Chapter II of the Communist

Manifesto, which starts by asserting that communists “have no interests

separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole” were never

discussed. Hearteningly, it was WRP members’ genuine concern with, and

connection to, the wider movement – particularly as it developed during the

1984-85 miners’ strike – that helped to ensure Healy’s rapid downfall, once the

issue of sexual abuse was brought into the open. I now think that, in terms of

the only “end” I understand – the movement to communism – the pre-1985 WRP was

worse than useless as a “means”, so its break-up was good. And it was

especially good that the issue of sexual abuse was placed at the centre.

the cases of the WRP and SWP might be connected, I think that there are

connections, and that they are not at all simple. Firstly, the WRP in some ways

manifested a particularly extreme version of left-wing sectishness, and in

other ways was a creature of a time now past (when so much trade union culture

was so openly macho, and Jimmy Savile was in his prime). But it would be silly

to ignore the connections on such grounds. In my view “revolutionary morality”,

by means of which young people who set out to overturn oppression put their

efforts into building organisations that end up reproducing aspects of

hierarchy and alienation, is an abiding theme.

it seems to me significant that not only the WRP but two left-wing

organisations of the 2000s, the Scottish Socialist Party and Respect, foundered

on “moral” issues. With Respect it was simple: the explicit defence of rape by

the loathsome George Galloway resulted in resignations. The SSP case seemed to

me less simple. The issue was not sexual abuse, or even sex. An issue

was members lying to each other, I think; another was a culture of mistrust.

These are “moral” issues too, and the WRP had them too.

|

| A monster certainly but one who was tolerated by too many like Ken Livingstone and ‘Red’ Ted Knight of Lambeth Council |

after the break-up of the WRP, a few people who participated – and many more

who did not – suggested that Healy’s sexual abuse was not “the central issue”,

and that his “political degeneration” was more important. As Cliff Slaughter

(who, like all the Marxist writers of the pre-1985 WRP, participated in the

opposition to Healy) insisted from the start, sexual abuse was the

central issue. What could be more important than unravelling and undoing the

processes by which a “revolutionary” organisation – in however complicated a

manner, and behind most of our backs – turned young women who sought to fight

oppression into victims of an abusive “leader”? What process could be more

immoral, from any truly revolutionary point of view? What on earth does all the

talk about “fighting capitalism” mean, if the forms of alienation that hold

capitalism together are reproduced in “revolutionary” organisations? And which

of these forms of alienation could be more central than the patriarchy and the

distorted relations between men and women, that preceded capitalism but are

essential elements of social relations dominated by capital? In my view, these

and similar issues are of paramount importance. I welcome discussion of all

this.

those who don’t know me. I joined the WRP’s predecessor, the Socialist Labour

League, at the age of 14 in 1971; was on the WRP central committee from 1982;

and after 1985 remained in a successor organisation (WRP/Workers Press)

until 1995. I was the editor of the mineworkers’ union newspaper, The Miner,

1990-95. Since 1990 I have travelled a great deal to Russia and Ukraine and

written on Russian history; I am the author of The Russian Revolution in

Retreat: Soviet workers and the new communist elite 1920-24. I am

active in social and labour movements.

repost and circulate.

By Corinna Lotz and Paul Feldman

Foreword by Ken Livingstone MP

Paul and Corinna have been friends of mine for over 13 years. When they

asked me to contribute a foreword to their biography of Gerry Healy I was

delighted. At a time when political memories are growing increasingly short, it

is good that the effort has been made to record the life of Gerry Healy, a

revolutionary Marxist who had a massive impact on the working class socialist

movement, in Britain and internationally.

The fashionable obsession with the “end of history” is no more

than a disguise for jettisoning valuable common experiences and major

contributions made by revolutionaries such as Gerry Healy. Naturally this suits

those who would like to bury for ever the memory of his unique concept of

political work.

I first met Gerry Healy in 1981, shortly after I became Leader of the

Greater London Council and was immediately captivated by his vivid recollection

of events and personalities on the left. He had recognised the changed

political climate which enabled Labour to take control of County Hall, and that

we were using the immense resources of the Greater London Council to support

those struggling for jobs and other rights.

Gerry Healy saw that it was possible to use the GLC as a rallying fortress

for Londoners who were opposed to Thatcher’s hard-line monetarism. Contrary to

the image spread by his opponents, I was impressed by the non-sectarian

approach that the News Line took on the reforms the GLC introduced. News

Line’s coverage was thorough and objective throughout our struggles. Given

we were under siege by the Fleet Street press, it was a relief to pick up the

WRP’s paper in the morning! The GLC’s public relations department usually put

the News Line articles on the front page of the daily press cuttings

bundle.

The first discussion I had with Gerry Healy made a great impact on me.

Coming from a party where long term thinking is usually defined by the next

opinion poll, I was challenged by the broad sweep of his knowledge and the

freshness of his approach. He knew how to operate in the political present

through his understanding of the movement of economic and social forces.

Although we were in totally different political organisations, Gerry Healy

always tried to find a point of connection with the world in which I moved. He

did this because he wanted to find ways of working with the left in the Labour

Party on common issues and principles. But he never laid down conditions. He

accepted that there were fundamental differences between us, but they should

not prevent us from collaborating against the Tories. It was a refreshing

change from the world of intrigues and back-stabbing politics of the Labour

Party. That is why I felt happy about speaking at News Line rallies, even

though I came under a lot of fire from those like Dennis Healey within my own

party.

During the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Gerry Healy and the News

Line worked with a group of us in the Labour Party to end Labour’s silence

on the repression of the Palestinian people. In the aftermath of the slaughter

of Palestinians in the Sabra and Shattila camps, we succeeded in winning the

recognition of the Palestine Liberation Organisation as the sole legitimate

representatives of the Palestinian People by the Labour Party Conference of

1982.

Gerry Healy and I both endured great upheavals during the 1985-1986 period

with the Tories abolishing the GLC and the WRP torn apart by a major split. We

lost touch for a time, but renewed contact a few years before he died because

of his work in the USSR. I was happy but not surprised to discover that we had

reached similar conclusions about the dramatic changes in the Soviet Union

during 1987-1989. Our last meeting in the summer of 1989 was devoted to a long

conversation about the significance of perestroika and glasnost. We both knew

that the events in the Soviet Union would change the lives of everyone in the

world, and especially those involved in socialist politics.

The other area we had a close understanding about was the role of the secret

services in Britain. We knew that joint campaigning between genuine Marxists

and socialists in the Labour Party was viewed as a dangerous threat by the

intelligence services. In particular, contacts between us and national

liberation movements such as the Palestinians drew even more attention from the

British state.

My own research and experiences have strengthened, not weakened, my

conviction that MI5 considers even the smallest left organisation worthy of

close surveillance and disruption. Given the pivotal role of Healy in

maintaining contact with Yasser Arafat’s HQ through the WRP’s use of the latest

technology, MI5 clearly felt that they had to stop the growing influence of the

WRP. I have never changed my belief that the split in the WRP during 1985 was

the work of MI5 agents.

It was a privilege to have worked with Gerry Healy. I know this book will

give those who did not know him an opportunity to understand his contribution

to the working class revolutionary movement.

Ken Livingstone MP

March 1994