Despite its Pretensions Socialist Zionism was simply an an attempt to reconcile the irreconcilable – Colonisation and Socialism

On Sunday at 5 pm, I will be giving a talk on my book Zionism During the Holocaust to the Communist Party of Great Britain and I intend to focus in particular on the reactionary and counter-revolutionary role of Zionism amongst the Jews of Europe. You can join using this link

I grew up in a Zionist household with all the myths of Zionism. I learnt that what we now call the Nakba (a word never used) was the Palestinians voluntarily leaving in order to make way for the invading Arab armies.

We were told that far from expelling the Arabs, the Zionists had begged them to stay! What was never mentioned was the use of barrel bombs against the Arab population of Haifa and the fact that they were forced to board ships to flee. Far from wanting to ‘drive the Jews into the sea’ the opposite was the case. It was the Palestinians who were driven into the sea, many of whom drowned.

Israel was seen as an oasis of socialism in a backward, feudal Arab Middle East. The Kibbutzim were held out as socialism in action and many were the times I was told that far from taking part in struggles here I should go and live on a Kibbutz. Of course I was never told that the Kibbutz was a racially pure institution, which no Arab could become a member of or that they were established as stockade and watchtower settlements on confiscated Arab land.

The myths of Zionism could, by themselves, fill a whole volume. Today of course people are wiser as the true nature of Zionism has revealed itself with the ascent to power of the Jewish Nazi Jewish Power (Otzma Yehudit) and the assorted freaks of Israel’s far-Right.

What is interesting is how it began. Is it true that when Zionism began amongst the Jewish masses in Czarist Russia that it was a progressive movement that over time has moved to the right? Was Zionism a good idea that turned out badly or was it born with the Mark of Cain?

The strategy of the founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, was a simple one. He wanted to establish a Jewish State and from the start he sought to find a partner from one of the imperialist powers. This was a strategy that the Zionist movement never deviated.

In 1917 Great Britain agreed to sponsor the Zionist colonisation of Palestine and it formalised its agreement in the Zionism Haifa Otzma Yehudit Balfour Declaration but before then Herzl had traipsed round the rulers of Europe – from the Ottoman Sultan, the German Kaiser, the Pope, Hungary’s King Victor Emmanuel and the Ministers of Czarist Russia.

Before the advent of Hitler and the Nazis the Czar of Russia was seen by most Jews as the symbol of murderous anti-Semitism. Pogroms against the Jews were seen as a means of diverting the wrath of the masses away from the Czarist regime and towards Jews living in the Pale of Settlement where they were confined.

To this end Czarist Interior Minister Vyacheslav von Plehve organised the Black Hundreds, a group of reactionary, counter-revolutionary, anti-Semitic groups during and after the Russian Revolution of 1905. They were responsible for hundreds of pogroms against Russian Jews and the death of thousands. They were supported by Czar Nicholas II who instructed his ministers to support and fund them.

The Bolsheviks and Russian workers were forced to fight them militarily. Lenin called them ‘tramps, rowdies, hawkers, and similar disreputable characters’. See The Black Hundreds and the Organisation of an Uprising

Russia had been plagued by pogroms against the Jews. Anti-Semitism was seen as the way of dividing the opposition to the Czarist regime. This was why, contrary to revisionist academics such as Brendan McGeever’s Bolsheviks and Anti-Semitism, the Bolsheviks took anti-Semitism very seriously as it was a weapon posed over the heart of the revolution.

The most famous pogrom was in Kishinev on 19- 20 April 1903. Nearly 50 Jews were killed and 92 were severely injured. ‘No Jewish event of the time would be as extensively documented.’ [Zipperstein, Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History] Reports in the New York Times and The Times ensured that it had an unprecedented impact internationally. [See Jewish Massacre Denounced’. NYT April 28 1903].

The attitude of the Hayim Nahman Bialik, the Zionist national poet, “In the City of Killing” was to talk of the ‘disgraceful shame and cowardice’ of the Jewish victims of the pogrom. The Zionists of course had done nothing to organise self-defence.

The Czarist regime refused to intervene except when the Jews defended themselves. The international and the liberal press in Russia were outraged by stories of rape, mutilation and the murder of children. The anti-Zionist Jewish Bund organised self-defence units here and elsewhere.

The Governor of Bessarabia, whose capital was Kishinev, was replaced by Prince Serge Urusov, a ‘severe critic of autocracy’. Urusov’s study of the massacre confirmed that it had been instigated by Plehve.

On August 8 1903, barely four months after the Kishinev pogrom, Herzl visited Russia, meeting with Plehve. Herzl was concerned that Zionism should retain its legal status. As he began explaining the merits of Zionism Plehve interrupted him: ‘You don’t have to justify the movement to me. Vous prêchez un converti.’ [You are preaching to a convert].’ [Herzl Diaries, pp. 1522-1525, 10.8.1903]

What was the response of the Zionists? Did they condemn the Czarist regime? Not at all. The 6th Zionist Congress which met on 23 August 1903 said nothing just as 30 years later in Prague, it would remain silent about the Hitler regime. It was more concerned with the Uganda Project.

Herzl asked Plehve: ‘Help me to reach land sooner and the revolt will end. And so will the defection to the Socialists.’ [Complete Diaries, p. 1526] Plehve approved the holding of the second Russian Zionist Conference, the publication of a Zionist daily, Der Fraind and the legalisation of the Zionist movement at a time when all other political organisations were banned.

Herzl promised that the revolutionaries would stop their struggle in return for a charter for Palestine in 15 years. The Bund were outraged. [Henry Tobias, The Jewish Bund in Russia – From Its Origins to 1905, p. 252] Kishinev created a crisis for the fledgling Labour Zionist groups, who realised that they could not ignore the struggle against anti-Semitism.

Herzl had earlier written to the Kaiser describing how:

our movement… has everywhere to fight an embittered battle with the revolutionary parties which rightly sense an adversary in it. We are in need of encouragement even though it has to be a carefully kept secret. [Complete Diaries, p. 59, October 17 1897]

Later when he came to London, in an interview with Lucien Wolf of the Board of Deputies, Plehve spoke favourably of Zionism as an encouragement to Jewish emigration. For ‘non-emigrants’ he thought that ‘Zionist ideas… might be useful as an antidote to Socialist doctrines.’ [The Times 6.2.04, ‘Mr Lucien Wolf’s Interview with M. de Plehve’].

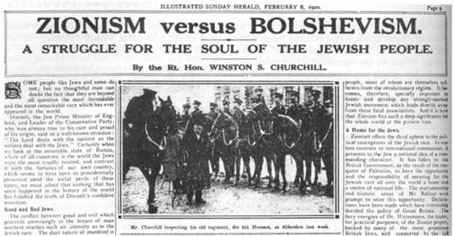

Sixteen years later, in February 1920 Winston Churchill wrote in Zionism v Bolshevism of a ‘worldwide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilisation’ by Jewish revolutionaries. In 1935 Ben-Gurion described Zionism as a ‘bulwark against assimilation and communism.’ [ https://tinyurl.com/y269wb72]

Socialist Zionism arose out of the contradiction between the needs of Jewish workers in Russia to fight anti-Semitism where they were and the dream of Palestine. Although Zionism had foresworn the struggle in the here and now, it couldn’t ignore the fact that Russian Jews were the oppressed of the oppressed. Socialist Zionism arose as a result of the conflict between Zionism’s support for the existing order and the Jewish proletariats’ class interests. [Lucas, Modern History of Israel, p. 35]

The myth of Zionist socialism in Palestine rested on the belief that the kibbutzim were socialist. In reality the kibbutzim were the result of an alliance between the Zionist labour movement and the Zionist financial institutions. The socialism of the pioneers did not prevent them from entering into an alliance with the Jewish bourgeoisie.

Collective colonisation was the most efficient and cost effective means of colonising Palestine. They were not a means of changing society. They were ‘tools in forging national sovereignty.’ [Ze’ev Sternhell, Founding Myths of Israel, p. 325] They fooled though westerners like Hannah Arendt who described them as ‘the most promising of all social experiments made in the 20th century.’ [Hannah Arendt, The Jew As Pariah, p. 185].

The internal social structure of the kibbutzim reflected their political role. Personal space was eliminated in favour of collectivism. They were a Zionist Sparta intended to produce fighters without personal attachments of affection to each other or their children. ‘Everything was the property of the collective including the individual’s thoughts.’ [Bloom, ‘What “The Father” had in mind,’ p. 346].

The kibbutzim were Jewish-only stockade and watchtower settlements, marking out the borders of a future Jewish State. They provided the organisational backbone of Haganah, the pre-state army and Palmach, the Zionist shock-troops. Although never more than 5% of Israel’s population, the kibbutzim produced a disproportionately high number of Israel’s officer corps.

As the pogroms intensified, Labor Zionist parties were drawn into the fight against anti-Semitism. In Poland Poale Zion split into a Right and Left at its February/March 1919 conference, with Left Poale Zion emerging as much the stronger. This was the forerunner of the split at the World Union of Poale Zion’s fifth world congress in Vienna in 1920. LPZ supported the Bolshevik revolution and attended the second and third congresses of the Communist International as observers. LPZ opposed the decision by PZ to rejoin the World Zionist Organisation [WZO], viewing it as bourgeois.

But in Palestine it was the right-wing of PZ which was stronger. Because of the rhythms of colonisation Palestine PZ gravitated to the right whereas Poale Zion’s diaspora sections were pulled to the left as a result of the class struggle and the fight against anti-Semitism.

In Russia the success of the revolutionaries in overthrowing the Czarist regime in February 1917 lessened the attraction of Zionism. At their conference in Petrograd in June 1917 the Russian Zionists omitted all mention of British sponsorship of the Zionists settlement in Palestine. [Leonard Stein, The Balfour Declaration. p. 437].

According to the Labor Zionists, the Jewish and Palestinian workers would unite against the Jewish bourgeoisie at the very same time that they were calling for a Boycott of Arab Labour! We can see the results in Israel today where the Israeli Labor Party and Meretz (Mapam) entered into a coalition government with the far-right. Far from achieving socialism, the ‘left’ Zionists have almost disappeared.