The permit regime has a chilling effect on day to day life and political activity

Israel confiscates solar

panels supplying power to village not connected to grid for 50 years

panels supplying power to village not connected to grid for 50 years

When we think of Apartheid, whether Israeli or South African, we think of discrimination, segregation and separation. But the essence of Apartheid was labour control and to organise this it was necessary to have a system of pass control. People could only move with the requisite paper. In South Africa this was a crude system and it fell into abeyance but in Israel it is highly sophisticated, with over 100 different varieties of permit. It is the means by which Israel segments and divides the Palestinians, setting one off against another.

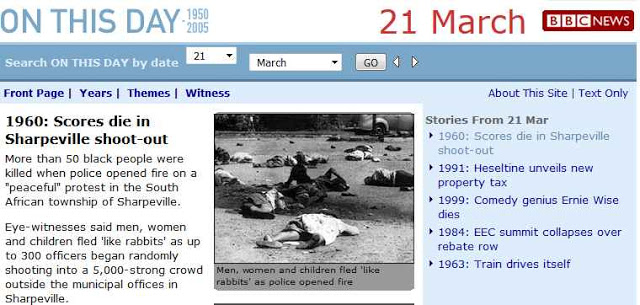

The fight against Apartheid in South Africa

began in earnest with the Sharpeville massacre on March 21st

1960. 69 Black Africans were gunned down

and 180 were injured when the Apartheid Police opened fire on an unarmed demonstration

of between 5,000 and 10,000 Africans who had been protesting against the

imposition of passes. The pass system

had been in operation in South Africa from 1800 until it was abolished in

1986. It had first been introduced to

control Black slaves.

In Israel and the apartheid analogy we learn that a permit and closure system was introduced in Israel in 1990. Leila Farsakh maintains that this system imposes “on Palestinians similar conditions to

those faced by blacks under the pass laws. Like the pass laws, the permit

system controlled population movement according to the settlers’ unilaterally

defined considerations.” In response to the al-Aqsa

intifada, Israel modified the

permit system and fragmented the West Bank and Gaza Strip territorially. “In April 2002 Israel declared that the

WBGS would be cut into eight main areas, outside which Palestinians could not

live without a permit.”

John Dugard has said

these laws “resemble, but in

severity go far beyond, apartheid’s pass system“. Jamal

Zahalka, an Israeli-Arab member of the Knesset for Balad said

that this permit system was a feature of apartheid. Azmi Bishara, a former

Knesset member, argued that the Palestinian situation had been caused by

“colonialist apartheid”

these laws “resemble, but in

severity go far beyond, apartheid’s pass system“. Jamal

Zahalka, an Israeli-Arab member of the Knesset for Balad said

that this permit system was a feature of apartheid. Azmi Bishara, a former

Knesset member, argued that the Palestinian situation had been caused by

“colonialist apartheid”

|

| How the BBC reported Sharpevill – the good old BBC bias was evident then when it described the massacre as a ‘shoot out’ as if the Africans had guns |

B’Tselem wrote in 2004, “Palestinians are barred from or have restricted access to 450

miles of West Bank roads” and has said this system has “clear

similarities” with the apartheid regime in South Africa

miles of West Bank roads” and has said this system has “clear

similarities” with the apartheid regime in South Africa

In October 2005 the Israel Defense Forces stopped

Palestinians from driving on Highway 60, as part of a plan for a separate Road Network for Palestinians and

Israelis in the West Bank. The road had been sealed after the fatal shooting of

three settlers near Bethlehem. As of 2005, no private Palestinian cars were

permitted on the road although public transport was still allowed.

Palestinians from driving on Highway 60, as part of a plan for a separate Road Network for Palestinians and

Israelis in the West Bank. The road had been sealed after the fatal shooting of

three settlers near Bethlehem. As of 2005, no private Palestinian cars were

permitted on the road although public transport was still allowed.

Whereas South Africa abolished its Pass Laws in

1986, in Israel they are maintained with full vigour. The West Bank is segmented with hundreds of

check points. Anyone who fools

themselves that this is not a military occupation is living on another plant.

1986, in Israel they are maintained with full vigour. The West Bank is segmented with hundreds of

check points. Anyone who fools

themselves that this is not a military occupation is living on another plant.

As the following article shows, Israel’s permit

system is far more sophisticated than that of South Africa and there are more

than 100 different types of permit, covering different areas and different

categories of person.

system is far more sophisticated than that of South Africa and there are more

than 100 different types of permit, covering different areas and different

categories of person.

Tony Greenstein

How

Israel’s permit regime costs Palestinians

Israel’s permit regime costs Palestinians

Rod Such The

Electronic Intifada 28 December 2017

Electronic Intifada 28 December 2017

Living Emergency: Israel’s Permit Regime in the Occupied West Bank by Yael

Berda, Stanford

University Press (2017)

Berda, Stanford

University Press (2017)

This slim book, only 152 pages long, contains volumes. Although it

focuses on a single aspect of the Israeli occupation – the use of permits to

control the Palestinian population – Israeli author Yael Berda manages to illuminate the occupation as a whole.

focuses on a single aspect of the Israeli occupation – the use of permits to

control the Palestinian population – Israeli author Yael Berda manages to illuminate the occupation as a whole.

The focus of Living Emergency is even narrower than the “permit

regime” implied in the subtitle, as it examines work permits specifically and,

in particular, the use of the security threat designation to deny work permits

to Palestinians.

regime” implied in the subtitle, as it examines work permits specifically and,

in particular, the use of the security threat designation to deny work permits

to Palestinians.

Living Emergency conveys a Kafkaesque world imposed on Palestinians

in the occupied West Bank who may one day find that a steady construction job

in Israel simply evaporates, a work permit denied and a livelihood destroyed by

classified rules and secret evidence. Many face a Catch-22, knowing that refusing

to become an informer in exchange for a work permit can be considered

resistance to the occupation and therefore a security threat in itself.

in the occupied West Bank who may one day find that a steady construction job

in Israel simply evaporates, a work permit denied and a livelihood destroyed by

classified rules and secret evidence. Many face a Catch-22, knowing that refusing

to become an informer in exchange for a work permit can be considered

resistance to the occupation and therefore a security threat in itself.

Berda is an attorney who represented hundreds of Palestinian clients

between 2005 and 2007 from her Jerusalem office. Those experiences form the

basis of this study of Israel’s “population management” strategies that have

also been described by other authors as Israel’s

“social engineering” or “matrix of control.”

between 2005 and 2007 from her Jerusalem office. Those experiences form the

basis of this study of Israel’s “population management” strategies that have

also been described by other authors as Israel’s

“social engineering” or “matrix of control.”

|

| In the seam zone |

Berda notes that her privileged status as a Jewish Israeli citizen

enabled her to gain access to information that Palestinian attorneys would

never receive, and that sexism – the perception that she was “harmless” and

“loyal” – opened the door to yet more revelations.

enabled her to gain access to information that Palestinian attorneys would

never receive, and that sexism – the perception that she was “harmless” and

“loyal” – opened the door to yet more revelations.

Israel imposes more than 100 different types of permits on Palestinians

in the West Bank. There are 13 types of permits just to travel within the “seam

zone” – the area around Israel’s wall in the West Bank that divides

Palestinians from their work, their hospitals and often their farmland.

in the West Bank. There are 13 types of permits just to travel within the “seam

zone” – the area around Israel’s wall in the West Bank that divides

Palestinians from their work, their hospitals and often their farmland.

Control

The permit regime has a chilling effect on political activity and

resistance to the occupation because of the fear of being classified as a

security threat. Having the power to award, revoke or deny permits enables

Israel to control those Palestinians who would attempt labor organizing and

improvement of work conditions, enables Israel to recruit informers and imposes

significant costs on Palestinian living standards and economic development.

resistance to the occupation because of the fear of being classified as a

security threat. Having the power to award, revoke or deny permits enables

Israel to control those Palestinians who would attempt labor organizing and

improvement of work conditions, enables Israel to recruit informers and imposes

significant costs on Palestinian living standards and economic development.

Berda points out that in 2005 the cost of a work permit for experienced

Palestinian construction workers could amount to half their salary. A more recent study found that

Palestinians typically paid a quarter to a third of their wages to job brokers,

or middlemen, who helped them find work in Israel and obtain the necessary

permits.

Palestinian construction workers could amount to half their salary. A more recent study found that

Palestinians typically paid a quarter to a third of their wages to job brokers,

or middlemen, who helped them find work in Israel and obtain the necessary

permits.

Berda observes that the permit regime grew out of the 1945 Defense

(Emergency) Regulations. These repressive regulations, which denied basic

democratic rights in order to prevent political activity, were established by

the British during the Mandate period. Zionist settlers despised the negative

effects such regulations had on them. Some even compared them to laws enacted

by the Nazis.

(Emergency) Regulations. These repressive regulations, which denied basic

democratic rights in order to prevent political activity, were established by

the British during the Mandate period. Zionist settlers despised the negative

effects such regulations had on them. Some even compared them to laws enacted

by the Nazis.

After Israel took control of the West Bank by force in 1967, the

occupation authorities set up administrative rules that were copied

word-for-word from the British regulations, changing only the titles of

functionaries and replacing terms like “His Majesty’s Forces” with “Israeli

forces.”

occupation authorities set up administrative rules that were copied

word-for-word from the British regulations, changing only the titles of

functionaries and replacing terms like “His Majesty’s Forces” with “Israeli

forces.”

The 1993 Oslo accords failed to dismantle the permit regime and instead

helped abet it.

helped abet it.

Initially, the accords curbed Israel’s ability to recruit Palestinian

collaborators due to the withdrawal of its military forces from many

Palestinian towns and cities. Without a physical presence in these areas, it

became more difficult for Israeli forces to identify potential informers.

collaborators due to the withdrawal of its military forces from many

Palestinian towns and cities. Without a physical presence in these areas, it

became more difficult for Israeli forces to identify potential informers.

However, Israel’s Shin Bet secret police soon realized that permit denials

could be used to coerce people to inform, one of the most pernicious aspects of

the permit regime.

could be used to coerce people to inform, one of the most pernicious aspects of

the permit regime.

Berda notes that this practice is a grave violation of the Fourth Geneva

Convention. Article 31 specifies that “No

physical or moral coercion shall be exercised against protected persons, in

particular to obtain information from them or from third parties.”

Convention. Article 31 specifies that “No

physical or moral coercion shall be exercised against protected persons, in

particular to obtain information from them or from third parties.”

The permit regime was injurious not only because failure to inform could

mean the loss of livelihood, but also because it induced paranoia and jealousy

among Palestinians.

mean the loss of livelihood, but also because it induced paranoia and jealousy

among Palestinians.

Obtaining a permit to work in Israel could in itself imply

collaboration, or a Palestinian previously denied a permit who later received

one could be suspected of agreeing to inform. Meanwhile, a jealous or grudgeful

acquaintance might approach Shin Bet with security accusations simply for

revenge.

collaboration, or a Palestinian previously denied a permit who later received

one could be suspected of agreeing to inform. Meanwhile, a jealous or grudgeful

acquaintance might approach Shin Bet with security accusations simply for

revenge.

“Living emergency”

Berda estimates that more than 200,000 Palestinians in the West Bank

have been labeled “security threats.” She notes that one of the most revealing

aspects of her work in defending those so labeled is how often the Shin Bet

withdrew the designation when met with a legal challenge, as if it “would

rather grant an individual request than expose its practices and

decision-making to judicial oversight.”

have been labeled “security threats.” She notes that one of the most revealing

aspects of her work in defending those so labeled is how often the Shin Bet

withdrew the designation when met with a legal challenge, as if it “would

rather grant an individual request than expose its practices and

decision-making to judicial oversight.”

The frequency with which this happened in her practice and that of other

human rights legal groups indicates the arbitrariness of the designation,

particularly since the legal system is designed to prevail on behalf of the

bureaucratic entities in charge of the permit system.

human rights legal groups indicates the arbitrariness of the designation,

particularly since the legal system is designed to prevail on behalf of the

bureaucratic entities in charge of the permit system.

The author is impressed with how many Palestinians have resisted the

permit regime by taking part in legal challenges, considering the risks they

assume, including the possibility of receiving a lifetime ban disqualifying

them from future permits. She takes to task some of Israel’s human rights

organizations, such as B’Tselem and Yesh Din, for merely seeking to reform the

permit regime when in her view it must be rejected “in its entirety.”

permit regime by taking part in legal challenges, considering the risks they

assume, including the possibility of receiving a lifetime ban disqualifying

them from future permits. She takes to task some of Israel’s human rights

organizations, such as B’Tselem and Yesh Din, for merely seeking to reform the

permit regime when in her view it must be rejected “in its entirety.”

The permit regime was founded on the perception among Israeli leaders

that Israel existed in an emergency situation and therefore needed to impose

draconian control over Palestinians simply for being Palestinian. Berda concludes

that the permit regime resulted in a “living emergency for millions of

Palestinians,” in which “race and racial hierarchy infused the practices and

routines” of a settler-colonial bureaucracy and made life difficult and

humiliating for its victims.

that Israel existed in an emergency situation and therefore needed to impose

draconian control over Palestinians simply for being Palestinian. Berda concludes

that the permit regime resulted in a “living emergency for millions of

Palestinians,” in which “race and racial hierarchy infused the practices and

routines” of a settler-colonial bureaucracy and made life difficult and

humiliating for its victims.

Consider, for example, that some of her cases led to “clemency pleas” in

which a person had to apologize for wrongdoing even though they had never done

anything wrong.

which a person had to apologize for wrongdoing even though they had never done

anything wrong.

The abuses against her Palestinian clients “eradicated my faith in

Israel’s legal system,” she writes, but it did not eradicate her faith “in the

possibility to change its political regime and demand citizenship and equal

rights for all the inhabitants from the Jordan River to the sea.”

Israel’s legal system,” she writes, but it did not eradicate her faith “in the

possibility to change its political regime and demand citizenship and equal

rights for all the inhabitants from the Jordan River to the sea.”

Rod Such is a former editor for World Book and Encarta encyclopedias. He

lives in Portland, Oregon, and is active with the Occupation-Free Portland

campaign.

lives in Portland, Oregon, and is active with the Occupation-Free Portland

campaign.

trapped between the separation barrier and the

Green Line, Palestinians living in the ‘Seam Zone’ are forced to reckon with a

Kafkaesque permit regime that appears designed to do one thing and one thing

only: make them give up and leave.

Green Line, Palestinians living in the ‘Seam Zone’ are forced to reckon with a

Kafkaesque permit regime that appears designed to do one thing and one thing

only: make them give up and leave.

By Idan Landau, translated by

Jordan Michaeli

Jordan Michaeli

|

| A Palestinian woman takes part in a demonstration against the Israeli army’s permit regime, Bidu, West Bank, August 30, 2009. (Photo: Activestills.org) |

Israeli NGO Hamoked:

Center for the Defense of the Individual published “The Permit Regime” earlier this year, a

report amazing in its discoveries and the level it details the parallel

universe Israel has created in the “Seam Zone,” the area between the separation

barrier and the Green Line. The bulk of the information in the report was

collected from UN reports (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs,

OCHA) and the State of Israel’s responses to 76 Supreme Court petitions filed

by Hamoked over the years. As expected, the report gained zero media coverage.

Center for the Defense of the Individual published “The Permit Regime” earlier this year, a

report amazing in its discoveries and the level it details the parallel

universe Israel has created in the “Seam Zone,” the area between the separation

barrier and the Green Line. The bulk of the information in the report was

collected from UN reports (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs,

OCHA) and the State of Israel’s responses to 76 Supreme Court petitions filed

by Hamoked over the years. As expected, the report gained zero media coverage.

The following 25

stations, on the journey to the land of permits, were drawn from the report.

Refreshment stations, scattered along the way, were taken from sources that

will be named.

stations, on the journey to the land of permits, were drawn from the report.

Refreshment stations, scattered along the way, were taken from sources that

will be named.

***

1. “The Seam Zone” –

Territories of the West Bank that were de facto annexed to Israel by the

separation wall. Today 7,500 Palestinians live in the Seam Zone, trapped

between the wall and the Green Line. With the completion of the wall their

number will increase to 30,000. Overall, the Seam Zone will expropriate 9.4

percent of the West Bank’s territory.

Territories of the West Bank that were de facto annexed to Israel by the

separation wall. Today 7,500 Palestinians live in the Seam Zone, trapped

between the wall and the Green Line. With the completion of the wall their

number will increase to 30,000. Overall, the Seam Zone will expropriate 9.4

percent of the West Bank’s territory.

2. More than half of

the land in the Seam Zone is private Palestinian land, expropriated

from residents living east of the wall.

the land in the Seam Zone is private Palestinian land, expropriated

from residents living east of the wall.

3. Palestinians must

apply for special permits to enter the Seam Zone. Moreover, permanent residents

of the villages in the Seam Zone must also apply for a permit that will allow

them to live on lands that have been theirs since time immemorial. In contrast

to the judicial principal according to which a person is entitled

to be on any part of his land except for in exceptional circumstances, wherein

the burden of proof lays on the authorities, in the Seam Zone,

the situation is completely reversed: no person is entitled to be on their land

except under exceptional circumstances, wherein the burden is on the person

to justify his or her presence.

apply for special permits to enter the Seam Zone. Moreover, permanent residents

of the villages in the Seam Zone must also apply for a permit that will allow

them to live on lands that have been theirs since time immemorial. In contrast

to the judicial principal according to which a person is entitled

to be on any part of his land except for in exceptional circumstances, wherein

the burden of proof lays on the authorities, in the Seam Zone,

the situation is completely reversed: no person is entitled to be on their land

except under exceptional circumstances, wherein the burden is on the person

to justify his or her presence.

4. Correction: The

burden of proof lays on the Palestinian, not on the person. The permit regime

in the Seam Zone is operated on the basis of ethnicity. Israelis and tourists

may move freely within and into the Seam Zone.

burden of proof lays on the Palestinian, not on the person. The permit regime

in the Seam Zone is operated on the basis of ethnicity. Israelis and tourists

may move freely within and into the Seam Zone.

***

The state of Israel

sees the permit regime as a regime of privilege… contrary to a rights-base

regime, which obligates the state to avoid infringing individual rights and even

to actively work toward their realization. In a regime of privilege the

sovereign can grant services to a certain population (or deny them) as part of

an administrative decision that is the prerogative of the state. (Phantom

Sovereign: The Bureaucracy of the Occupation in the West Bank, Yael Berda, Van

Leer Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing, 2012, pg 89)

sees the permit regime as a regime of privilege… contrary to a rights-base

regime, which obligates the state to avoid infringing individual rights and even

to actively work toward their realization. In a regime of privilege the

sovereign can grant services to a certain population (or deny them) as part of

an administrative decision that is the prerogative of the state. (Phantom

Sovereign: The Bureaucracy of the Occupation in the West Bank, Yael Berda, Van

Leer Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing, 2012, pg 89)

***

5. The “exceptional

circumstances” that allow one’s presence within the Seam Zone are divided into

13 categories, resulting in 13 kinds of permits: a proof of permanent residency

document, a permanent farmer permit, a temporary farmer permit, a business

permit, an employment permit, a personal needs permit, an education worker

permit, an international organization employee permit, a Palestinian Authority

employee permit, an infrastructure worker permit, a medical personnel permit, a

student permit and a minor child permit.

circumstances” that allow one’s presence within the Seam Zone are divided into

13 categories, resulting in 13 kinds of permits: a proof of permanent residency

document, a permanent farmer permit, a temporary farmer permit, a business

permit, an employment permit, a personal needs permit, an education worker

permit, an international organization employee permit, a Palestinian Authority

employee permit, an infrastructure worker permit, a medical personnel permit, a

student permit and a minor child permit.

6. The words

“permanent resident” and “permanent farmer” are deceiving: all permits in the

Seam Zone are temporary. Most of them are granted for three months and the

longest permit is granted for two years. As a Palestinian, your status

in the Seam Zone is always temporary, even if you were born and have

worked there your entire life. Additionally, Civil Administration inspectors

are likely to follow you around and may add you to the “Suspected of losing

connection to the Seam Zone” list – the code name for a transfer list used to

revoke his residency.

“permanent resident” and “permanent farmer” are deceiving: all permits in the

Seam Zone are temporary. Most of them are granted for three months and the

longest permit is granted for two years. As a Palestinian, your status

in the Seam Zone is always temporary, even if you were born and have

worked there your entire life. Additionally, Civil Administration inspectors

are likely to follow you around and may add you to the “Suspected of losing

connection to the Seam Zone” list – the code name for a transfer list used to

revoke his residency.

7. A permit granted

for one purpose may not be used for another. A person who received a farming

permit in the Seam Zone cannot use it to travel to a family gathering; they

must apply for a special “personal needs permit.” A person who received an

“infrastructure worker” permit cannot use the same permit to conduct business,

and so on and so forth. Moreover, the army does not handle more than one

application per person at any given time. The result is that there’s no real

possibility to live an organic, multi-dimensional life in the Seam Zone, only,

at best, to divide it into a stream of events, disconnected from each other in

time.

for one purpose may not be used for another. A person who received a farming

permit in the Seam Zone cannot use it to travel to a family gathering; they

must apply for a special “personal needs permit.” A person who received an

“infrastructure worker” permit cannot use the same permit to conduct business,

and so on and so forth. Moreover, the army does not handle more than one

application per person at any given time. The result is that there’s no real

possibility to live an organic, multi-dimensional life in the Seam Zone, only,

at best, to divide it into a stream of events, disconnected from each other in

time.

***

From the perspective

of the colonial model, the merging of the security and civilian mechanisms is

actually a desirable one, because it allows administrative flexibility and the

manufacturing of exceptions on an ongoing, daily basis, thanks to the recurring

states of security emergency – until even civilian considerations become

reactive and operate in emergency mode. (Phantom Sovereign: The Bureaucracy of

the Occupation in the West Bank, pg 90)

of the colonial model, the merging of the security and civilian mechanisms is

actually a desirable one, because it allows administrative flexibility and the

manufacturing of exceptions on an ongoing, daily basis, thanks to the recurring

states of security emergency – until even civilian considerations become

reactive and operate in emergency mode. (Phantom Sovereign: The Bureaucracy of

the Occupation in the West Bank, pg 90)

***

8. The army does not

issue farming permits to joint owners of land. One owner will receive a permit,

the other won’t. The only way for the other owners to access their land is by

applying for a permit as a “temporary worker,” employed by the owner holding

the permit. For this they must present a work contract. Palestinians are forced

to sign work contracts with their parents, children and siblings.

issue farming permits to joint owners of land. One owner will receive a permit,

the other won’t. The only way for the other owners to access their land is by

applying for a permit as a “temporary worker,” employed by the owner holding

the permit. For this they must present a work contract. Palestinians are forced

to sign work contracts with their parents, children and siblings.

9. The number of

Palestinians holding permits is steadily decreasing, while the number of

permits issued remains identical. The reason is that the time period for the

permits are valid is becoming ever shorter. Between 2007 and 2010 the number of

permits granted for two years decreased from 23 to 7 percent of all permits.

Palestinians holding permits is steadily decreasing, while the number of

permits issued remains identical. The reason is that the time period for the

permits are valid is becoming ever shorter. Between 2007 and 2010 the number of

permits granted for two years decreased from 23 to 7 percent of all permits.

***

What characterizes

the administrative flexibility of the permit regime is, in fact, that the

squandering of resources and the frequent administrative friction involved in

providing work permits brings about two results desired by the governmental

system: creating a dependency of the population on the administrative system in

order to preserve ample space for monitoring and control; and preventing the

entry of Palestinians from the West Bank into Israel. (Phantom Sovereign: The

Bureaucracy of the Occupation in the West Bank, pg 88)

the administrative flexibility of the permit regime is, in fact, that the

squandering of resources and the frequent administrative friction involved in

providing work permits brings about two results desired by the governmental

system: creating a dependency of the population on the administrative system in

order to preserve ample space for monitoring and control; and preventing the

entry of Palestinians from the West Bank into Israel. (Phantom Sovereign: The

Bureaucracy of the Occupation in the West Bank, pg 88)

***

10. As a result of

the permits’ short validity, the difficulty of renewing them on time and delays

faced at Israeli check points, farmlands in the Seam Zone are not regularly

cultivated. Greenhouses have been taken down, crops such as citrus and almonds

were abandoned, and for the most part, only olive trees, which provide less

revenue, remain. Due to difficulties in reaching the land, the yields from

olive harvest also decreased 60 percent, compared to yields on the eastern side

of the fence. In short, the permit regime transformed the Seam Zone into an area

of economic impoverishment.

the permits’ short validity, the difficulty of renewing them on time and delays

faced at Israeli check points, farmlands in the Seam Zone are not regularly

cultivated. Greenhouses have been taken down, crops such as citrus and almonds

were abandoned, and for the most part, only olive trees, which provide less

revenue, remain. Due to difficulties in reaching the land, the yields from

olive harvest also decreased 60 percent, compared to yields on the eastern side

of the fence. In short, the permit regime transformed the Seam Zone into an area

of economic impoverishment.

11. The circle of

life and death of a ‘permit’: File an application at the Palestinian District

Coordination and Liaison (DCO) Office → forward it to the Israeli DCO

→ permit is granted, outright procedural rejection or refusal → in

case of refusal, file an appeal at the Israeli DCO → be summoned to a

committee hearing → the permit is granted or it is refused → in case

of refusal, appeal to the High Court of Justice.

life and death of a ‘permit’: File an application at the Palestinian District

Coordination and Liaison (DCO) Office → forward it to the Israeli DCO

→ permit is granted, outright procedural rejection or refusal → in

case of refusal, file an appeal at the Israeli DCO → be summoned to a

committee hearing → the permit is granted or it is refused → in case

of refusal, appeal to the High Court of Justice.

12. There is

potential for trouble at every step in the process. Many times, the same

application will be filed again and again since the Israeli DCO claims that an

application “was not transferred” to it. The length of the delay between the

Palestinian DCO (which only acts as an intermediary) and the Israeli DCO is

unknown. A Palestinian has no way of knowing the status of his or her

application, whether it reached its destination, whether documents are missing,

and so on. Applications are often rejected without informing the applicant. The

delay is crucial, since those who don’t file an appeal within a set period of

time after being rejected must wait another six months before filing a new

appeal. Filing an appeal also involves a risk: the military does not issue

written confirmations when receiving appeals, thus making it difficult to prove

that an appeal was ever made. Even if you are summoned to appear in front a

committee hearing following an appeal, there is no guarantee that the subpoena

will arrive on time. Many Palestinians have missed their hearings simply

because they were not informed of them. Of course, not appearing at a hearing

is the equivalent of not submitting an appeal at all. The refusal is then

automatically extended for six months.

potential for trouble at every step in the process. Many times, the same

application will be filed again and again since the Israeli DCO claims that an

application “was not transferred” to it. The length of the delay between the

Palestinian DCO (which only acts as an intermediary) and the Israeli DCO is

unknown. A Palestinian has no way of knowing the status of his or her

application, whether it reached its destination, whether documents are missing,

and so on. Applications are often rejected without informing the applicant. The

delay is crucial, since those who don’t file an appeal within a set period of

time after being rejected must wait another six months before filing a new

appeal. Filing an appeal also involves a risk: the military does not issue

written confirmations when receiving appeals, thus making it difficult to prove

that an appeal was ever made. Even if you are summoned to appear in front a

committee hearing following an appeal, there is no guarantee that the subpoena

will arrive on time. Many Palestinians have missed their hearings simply

because they were not informed of them. Of course, not appearing at a hearing

is the equivalent of not submitting an appeal at all. The refusal is then

automatically extended for six months.

***

In the Castle the

telephone works beautifully of course, I’ve been told it’s going there all the

time, that naturally speeds up the work a great deal. We can hear this

continual telephoning in our telephones down here as a humming and singing, you

must have heard it too. Now this humming and singing transmitted by our

telephones is the only real and reliable thing you’ll hear, everything else is

deceptive. There’s no fixed connexion with the Castle, no central exchange

transmits our calls further. When anybody calls up the Castle from here the

instruments in all the subordinate departments ring, or rather they would all

ring if practically all the departments – I know it for a certainty – didn’t

leave their receivers off. Now and then, however, a fatigued official may feel

the need of a little distraction, especially in the evenings and at night and

may hang the receiver on. Then we get an answer, but an answer of course that’s

merely a practical joke. And that’s very understandable too. For who would take

the responsibility of interrupting, in the middle of the night, the extremely

important work up there that goes on furiously the whole time, with a message

about his own little private troubles? (Franz Kafka, The Castle)

telephone works beautifully of course, I’ve been told it’s going there all the

time, that naturally speeds up the work a great deal. We can hear this

continual telephoning in our telephones down here as a humming and singing, you

must have heard it too. Now this humming and singing transmitted by our

telephones is the only real and reliable thing you’ll hear, everything else is

deceptive. There’s no fixed connexion with the Castle, no central exchange

transmits our calls further. When anybody calls up the Castle from here the

instruments in all the subordinate departments ring, or rather they would all

ring if practically all the departments – I know it for a certainty – didn’t

leave their receivers off. Now and then, however, a fatigued official may feel

the need of a little distraction, especially in the evenings and at night and

may hang the receiver on. Then we get an answer, but an answer of course that’s

merely a practical joke. And that’s very understandable too. For who would take

the responsibility of interrupting, in the middle of the night, the extremely

important work up there that goes on furiously the whole time, with a message

about his own little private troubles? (Franz Kafka, The Castle)

***

13. Thirty percent of

all applications are rejected. Either the army denies the application was ever

transferred to it, or the applicant, according to the army, didn’t “prove a

need” to enter or be in the Seam Zone, or the army has security related

information on the applicant. In any case – the rejection is not explained, or

even handed down in writing.

all applications are rejected. Either the army denies the application was ever

transferred to it, or the applicant, according to the army, didn’t “prove a

need” to enter or be in the Seam Zone, or the army has security related

information on the applicant. In any case – the rejection is not explained, or

even handed down in writing.

14. The army requires

applicants to present documents that already appear in its database (land

ownership, payments of fees and so forth). Often the documents are kept at the

Civil Administration’s office. A Palestinian resident is thus forced to make

their way to the office (a procedure that is made difficult by travel

limitations – the same limitations that the permit is meant to remove), make a

copy of the sought-after document and take it to the Palestinian DCO, only for

the latter to return the copy to the Civil Administration office.

applicants to present documents that already appear in its database (land

ownership, payments of fees and so forth). Often the documents are kept at the

Civil Administration’s office. A Palestinian resident is thus forced to make

their way to the office (a procedure that is made difficult by travel

limitations – the same limitations that the permit is meant to remove), make a

copy of the sought-after document and take it to the Palestinian DCO, only for

the latter to return the copy to the Civil Administration office.

15. In principle,

there is no need for documents when renewing a permit. In practice, an

application made once an old permit expires is labeled a “new request” and all

of the documents must be attached to it.

there is no need for documents when renewing a permit. In practice, an

application made once an old permit expires is labeled a “new request” and all

of the documents must be attached to it.

16. The problem is,

that for a long period of time the Israeli DCO refused to accept applications

for permits before the old permit expired. That created lengthy interim periods

between permits, during which entrance to the Seam Zone was denied (fields were

neglected, family gatherings postponed). Two years ago the army agreed to

accept applications for extension starting three weeks before a permit expires

– an awfully short time in the DCO’s bureaucracy, in practice not allowing for

consecutiveness in between permits.

that for a long period of time the Israeli DCO refused to accept applications

for permits before the old permit expired. That created lengthy interim periods

between permits, during which entrance to the Seam Zone was denied (fields were

neglected, family gatherings postponed). Two years ago the army agreed to

accept applications for extension starting three weeks before a permit expires

– an awfully short time in the DCO’s bureaucracy, in practice not allowing for

consecutiveness in between permits.

17. Following a

petition to the Supreme Court in April 2011 the army updated its orders and

declared that permit applications for those living outside the Seam Zone will

be decided upon within 14 days. An examination of 195 applications filed during

the first half of 2012 revealed that the army kept to its own time frame in

only 7 percent of the cases.

petition to the Supreme Court in April 2011 the army updated its orders and

declared that permit applications for those living outside the Seam Zone will

be decided upon within 14 days. An examination of 195 applications filed during

the first half of 2012 revealed that the army kept to its own time frame in

only 7 percent of the cases.

***

And now I come to a

peculiar characteristic of our administrative apparatus. Along with its

precision it’s extremely sensitive as well. When an affair has been weighed for

a very long time, it may happen, even before the matter has been fully

considered, that suddenly in a flash the decision comes in some unforeseen

place, that, moreover, can’t be found any longer later on, a decision that

settles the matter, if in most cases justly, yet all the same arbitrarily. It’s

as if the administrative apparatus were unable any longer to bear the tension,

the year-long irritation caused by the same affair – probably trivial in itself

– and had hit upon the decision by itself, without the assistance of the

officials. Of course a miracle didn’t happen and certainly it was some clerk

who hit upon the solution or the unwritten decision, but in any case it

couldn’t be discovered by us, at least by us here, or even by the Head Bureau,

which clerk had decided in this case and on what grounds. The Control Officials

only discovered that much later, but we will never learn it; besides by this

time it would scarcely interest anybody. Now, as I said, it’s just these

decisions that are generally excellent. The only annoying thing about them –

it’s usually the case with such things – is that one learns too late about them

and so in the meantime keeps on still passionately canvassing things that were

decided long ago. (Franz Kafka, The Castle)

peculiar characteristic of our administrative apparatus. Along with its

precision it’s extremely sensitive as well. When an affair has been weighed for

a very long time, it may happen, even before the matter has been fully

considered, that suddenly in a flash the decision comes in some unforeseen

place, that, moreover, can’t be found any longer later on, a decision that

settles the matter, if in most cases justly, yet all the same arbitrarily. It’s

as if the administrative apparatus were unable any longer to bear the tension,

the year-long irritation caused by the same affair – probably trivial in itself

– and had hit upon the decision by itself, without the assistance of the

officials. Of course a miracle didn’t happen and certainly it was some clerk

who hit upon the solution or the unwritten decision, but in any case it

couldn’t be discovered by us, at least by us here, or even by the Head Bureau,

which clerk had decided in this case and on what grounds. The Control Officials

only discovered that much later, but we will never learn it; besides by this

time it would scarcely interest anybody. Now, as I said, it’s just these

decisions that are generally excellent. The only annoying thing about them –

it’s usually the case with such things – is that one learns too late about them

and so in the meantime keeps on still passionately canvassing things that were

decided long ago. (Franz Kafka, The Castle)

***

18. All application

procedures, appeals and hearings are covered in a 60-page booklet, the Standing

Orders for the Seam Zone (SO). Although the SO is meant for use by the Palestinian

population, it is written in Hebrew and not Arabic and is formulated in an

unclear legal language.

procedures, appeals and hearings are covered in a 60-page booklet, the Standing

Orders for the Seam Zone (SO). Although the SO is meant for use by the Palestinian

population, it is written in Hebrew and not Arabic and is formulated in an

unclear legal language.

19. The Israeli DCOs

are staffed not only by its clerks but also by Shin Bet officers. Palestinians

who file an appeal find themselves in front of a Shin Bet agent who pressures

them to become collaborators. Those who refuse can expect to receive their

permit only after a processing time of many months, if at all. This dilemma

dissuades many Palestinians from even trying to appeal a refusal: in the years

2007 – 2010, less than 3 percent of all rejected applicants were summoned to a

hearing.

are staffed not only by its clerks but also by Shin Bet officers. Palestinians

who file an appeal find themselves in front of a Shin Bet agent who pressures

them to become collaborators. Those who refuse can expect to receive their

permit only after a processing time of many months, if at all. This dilemma

dissuades many Palestinians from even trying to appeal a refusal: in the years

2007 – 2010, less than 3 percent of all rejected applicants were summoned to a

hearing.

20. You filed an

application, you were turned down, you filed an appeal and were summoned to the

committee hearing – then what? Sometimes the committee decides to conduct an

on-the-ground tour before coming to a decision. Six months can pass until the

tour takes place – another six months of delays before granting a permit.

According to the SO, a temporary three-month permit must be given to the

applicant during that time (as if another kind of permit exists). In reality,

such temporary permits are seldom granted. When they are granted, they are so

temporary they must be often renewed. As a result, while waiting for a

“non-temporary” permit (the length of which won’t be more than six months in

most cases), one must handle constant extensions of short term permits.

application, you were turned down, you filed an appeal and were summoned to the

committee hearing – then what? Sometimes the committee decides to conduct an

on-the-ground tour before coming to a decision. Six months can pass until the

tour takes place – another six months of delays before granting a permit.

According to the SO, a temporary three-month permit must be given to the

applicant during that time (as if another kind of permit exists). In reality,

such temporary permits are seldom granted. When they are granted, they are so

temporary they must be often renewed. As a result, while waiting for a

“non-temporary” permit (the length of which won’t be more than six months in

most cases), one must handle constant extensions of short term permits.

***

When one cannot find

the sovereign one also cannot appeal the sovereign’s decisions, learn his

decision-making patterns and adapt to them or change them. Still, as this is a

constant situation of emergency, sovereign power is present in nearly every

decision, even if it cannot be pinpointed as responsible. The ruling mechanism

prefers personal control over comprehensive policy, because the former can be changed

at any time, without any need for a cumbersome, organized legal system of

decision-making. (Phantom Sovereign: The Bureaucracy of the Occupation in the

West Bank, pg 111)

the sovereign one also cannot appeal the sovereign’s decisions, learn his

decision-making patterns and adapt to them or change them. Still, as this is a

constant situation of emergency, sovereign power is present in nearly every

decision, even if it cannot be pinpointed as responsible. The ruling mechanism

prefers personal control over comprehensive policy, because the former can be changed

at any time, without any need for a cumbersome, organized legal system of

decision-making. (Phantom Sovereign: The Bureaucracy of the Occupation in the

West Bank, pg 111)

***

21. Bureaucratic

reasons have made residents of the Seam Zone ineligible for marriage. Those who

marry Seam Zone residents are unable to obtain a permanent permit to be there

(only a few receive a permanent residency permit, which is also, as previously

mentioned, valid only for two years). A Seam Zone resident who moves in with a

spouse out of the Seam Zone “loses their connection” to it, according to the

army’s definition, and consequently loses their residency permit.

reasons have made residents of the Seam Zone ineligible for marriage. Those who

marry Seam Zone residents are unable to obtain a permanent permit to be there

(only a few receive a permanent residency permit, which is also, as previously

mentioned, valid only for two years). A Seam Zone resident who moves in with a

spouse out of the Seam Zone “loses their connection” to it, according to the

army’s definition, and consequently loses their residency permit.

22. The loop:

a couple from the Jenin area was married at the beginning of November

2009. The distance between their houses was less than one kilometer, but in

between runs the separation wall. The man applied for a “new seam zone

resident” document. His request was denied on the basis that “the applicant is

not a permanent resident.”

a couple from the Jenin area was married at the beginning of November

2009. The distance between their houses was less than one kilometer, but in

between runs the separation wall. The man applied for a “new seam zone

resident” document. His request was denied on the basis that “the applicant is

not a permanent resident.”

23. In February 2004

in a reply to the High Court, the State Attorney declared that

Palestinian farmers will be granted free entry to the Seam Zone through

“passages open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.” That was an empty promise.

Dozens of gates are positioned along the Seam Zone border; only two of them are

continuously open. It is no coincidence that they are the only two gates that

also serve settlers.

in a reply to the High Court, the State Attorney declared that

Palestinian farmers will be granted free entry to the Seam Zone through

“passages open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.” That was an empty promise.

Dozens of gates are positioned along the Seam Zone border; only two of them are

continuously open. It is no coincidence that they are the only two gates that

also serve settlers.

24. Any permit, of

any kind, after it was obtained by hard work – may be confiscated on the spot.

An army officer standing at a checkpoint may decide the permit holder deviated

from the conditions of the permit and confiscate it then and there. There is no

judicial oversight of confiscation; often the person whose permit was

confiscated does not receive a document attesting the confiscation and they are

not told of the possibility of filling an appeal.

any kind, after it was obtained by hard work – may be confiscated on the spot.

An army officer standing at a checkpoint may decide the permit holder deviated

from the conditions of the permit and confiscate it then and there. There is no

judicial oversight of confiscation; often the person whose permit was

confiscated does not receive a document attesting the confiscation and they are

not told of the possibility of filling an appeal.

25. The Seam Zone was

closed to Palestinian movement in 2002, when the permit regime was established.

In April 2011 the Supreme Court rejected petitions against it and ruled it is a

“temporary situation, resulting from a difficult, interim reality.” For over 10

years this situation hasn’t been temporary, although it’s the source of said

difficult reality.

closed to Palestinian movement in 2002, when the permit regime was established.

In April 2011 the Supreme Court rejected petitions against it and ruled it is a

“temporary situation, resulting from a difficult, interim reality.” For over 10

years this situation hasn’t been temporary, although it’s the source of said

difficult reality.

***

A few fundamental truths

Contrary to common

belief, the permit regime in the West Bank wasn’t established as a response to

a wave of Palestinian terror that started in 1994, but three years earlier in

January 1991 (Hebrew). Severe

restrictions on movement, which created a de facto separation between

Palestinian populations, prepared the ground for the Oslo accords, which were

based on the logic of separation. An investigation in 2011 revealed that the

Civil Administration issues Palestinians 101

different kinds of entry permits to Israel.

belief, the permit regime in the West Bank wasn’t established as a response to

a wave of Palestinian terror that started in 1994, but three years earlier in

January 1991 (Hebrew). Severe

restrictions on movement, which created a de facto separation between

Palestinian populations, prepared the ground for the Oslo accords, which were

based on the logic of separation. An investigation in 2011 revealed that the

Civil Administration issues Palestinians 101

different kinds of entry permits to Israel.

The Seam Zone is a

bureaucratic monster, illegal and immoral since day one. It’s the result of the

Israeli desire for annexation and the decision to build the separation wall

beyond the Green Line. The International

Court of Justice in The Hague ruled as follows on July 9, 2004,

sections 141 and 163:

bureaucratic monster, illegal and immoral since day one. It’s the result of the

Israeli desire for annexation and the decision to build the separation wall

beyond the Green Line. The International

Court of Justice in The Hague ruled as follows on July 9, 2004,

sections 141 and 163:

The fact remains that Israel has to face numerous indiscriminate and

deadly acts of violence against its civilian population. It has the right,

and indeed the duty, to respond in order to protect the life of its

citizens. The measures taken are bound nonetheless to remain in conformity

with applicable international law … Israel is under an obligation to

cease forthwith the works of construction of the wall being built in

the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including in and around East Jerusalem

[and] to dismantle forthwith the structure therein situated.

deadly acts of violence against its civilian population. It has the right,

and indeed the duty, to respond in order to protect the life of its

citizens. The measures taken are bound nonetheless to remain in conformity

with applicable international law … Israel is under an obligation to

cease forthwith the works of construction of the wall being built in

the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including in and around East Jerusalem

[and] to dismantle forthwith the structure therein situated.

The end goal of the

permit regime in the Seam Zone, like the limitations on movement and

construction in the Jordan Valley (Hebrew), is to gradually

thin out the indigenous Palestinian population and to clear lands for the

benefit of Israeli settlements. The method: revocation of permanent residency

(forced transfer), prevention of agricultural and economic development,

destruction of local communal and family structures, and turning day-to-day routines into bureaucratic nightmares that will eventually make

them hate life and leave the area – a voluntary transfer to complete the forced

transfer.

permit regime in the Seam Zone, like the limitations on movement and

construction in the Jordan Valley (Hebrew), is to gradually

thin out the indigenous Palestinian population and to clear lands for the

benefit of Israeli settlements. The method: revocation of permanent residency

(forced transfer), prevention of agricultural and economic development,

destruction of local communal and family structures, and turning day-to-day routines into bureaucratic nightmares that will eventually make

them hate life and leave the area – a voluntary transfer to complete the forced

transfer.

***

In this life it might easily happen, if he were not always on his

guard, until one day or other, in spite of the amiability of the authorities

and the scrupulous fulfillment of all his exaggeratedly light duties, he might

– deceived by the apparent favor shown him – conduct himself so imprudently

that he might get a fall; and the authorities, still ever mild and friendly,

and as it were against their will but in the name of some public regulation

unknown to him, might have to come and clear him out of the way. (Franz

Kafka, The Castle)

guard, until one day or other, in spite of the amiability of the authorities

and the scrupulous fulfillment of all his exaggeratedly light duties, he might

– deceived by the apparent favor shown him – conduct himself so imprudently

that he might get a fall; and the authorities, still ever mild and friendly,

and as it were against their will but in the name of some public regulation

unknown to him, might have to come and clear him out of the way. (Franz

Kafka, The Castle)

This post was first published in Hebrew on Idan Landau’s blog.

Planning

Policy in the West Bank

Israel’s planning and building policy in the West

Bank is aimed at preventing Palestinian development and dispossessing

Palestinians of their land. This is masked by use of the same professional and

legal terms applied to development in settlements and in Israel proper, such as

“planning and building laws”, “urban building plans (UBPs)”, “planning

proceedings” and “illegal construction”. However, while the planning and

building laws benefit Jewish communities by regulating development and

balancing different needs, they serve the exact opposite purpose when applied

to Palestinian communities in the West Bank. There, Israel exploits the law to

prevent development, thwart planning and carry out demolitions. This is part of

a broader political agenda to maximize the use of West Bank resources for

Israeli needs, while minimizing the land reserves available to Palestinians.

Bank is aimed at preventing Palestinian development and dispossessing

Palestinians of their land. This is masked by use of the same professional and

legal terms applied to development in settlements and in Israel proper, such as

“planning and building laws”, “urban building plans (UBPs)”, “planning

proceedings” and “illegal construction”. However, while the planning and

building laws benefit Jewish communities by regulating development and

balancing different needs, they serve the exact opposite purpose when applied

to Palestinian communities in the West Bank. There, Israel exploits the law to

prevent development, thwart planning and carry out demolitions. This is part of

a broader political agenda to maximize the use of West Bank resources for

Israeli needs, while minimizing the land reserves available to Palestinians.

The 1995 Oslo II Accord divided the West Bank into

three types of areas. Concentrations of Palestinian population in built-up

areas, which were – and still are – home to most of the Palestinian population

in the West Bank, were designated Areas A and B and officially handed over to

Palestinian Authority control. They are dotted throughout the West Bank in 165

disconnected ‘islands’. The remaining 61% of the West Bank were designated Area

C – the land mass surrounding Areas A and B, where Israel retains full control

over security and civil affairs, including planning, building, laying

infrastructure and development. This artificial division, which was meant to

remain in effect for five years only, does not reflect geographic reality or

Palestinian space.

three types of areas. Concentrations of Palestinian population in built-up

areas, which were – and still are – home to most of the Palestinian population

in the West Bank, were designated Areas A and B and officially handed over to

Palestinian Authority control. They are dotted throughout the West Bank in 165

disconnected ‘islands’. The remaining 61% of the West Bank were designated Area

C – the land mass surrounding Areas A and B, where Israel retains full control

over security and civil affairs, including planning, building, laying

infrastructure and development. This artificial division, which was meant to

remain in effect for five years only, does not reflect geographic reality or

Palestinian space.

In the West Bank, the potential for urban,

agricultural and economic development remains in Area C. Israel uses its

control over the area to quash Palestinian planning and building. In about 70%

of Area C – 42% of the West Bank – Israel has blocked Palestinian development

by designating large swathes of land as state land, survey land, firing zones,

nature reserves and national parks; by allocating land to settlements and their

regional councils; or by introducing prohibitions to the area now trapped

between the Separation Barrier and the Green Line (the boundary between

Israel’s sovereign territory and the West Bank).

agricultural and economic development remains in Area C. Israel uses its

control over the area to quash Palestinian planning and building. In about 70%

of Area C – 42% of the West Bank – Israel has blocked Palestinian development

by designating large swathes of land as state land, survey land, firing zones,

nature reserves and national parks; by allocating land to settlements and their

regional councils; or by introducing prohibitions to the area now trapped

between the Separation Barrier and the Green Line (the boundary between

Israel’s sovereign territory and the West Bank).

Even in the remaining 30% of Area C, Israel

restricts Palestinian construction by seldom approving requests for building

permits, whether for housing, for agricultural or public uses, or for laying

infrastructure. The Civil Administration (CA) – the branch of the Israeli

military designated to handle civil matters in Area C – refuses to prepare

outline plans for the vast majority of Palestinian communities there. Until

September 2015, it had prepared and approved plans for just 16 of the 180

Palestinian communities located entirely within Area C. The approved plans span

less than 1% of Area C, and relate to land that has largely been built up

already. The plans were drawn up without consulting the communities and do not

meet international planning standards. Their boundaries run close to the

built-up areas of the villages, leaving out land for farming, grazing flocks

and future development. From 2010 to 2015, the Palestinian Authority prepared

108 outline plans for 116 communities in Area C, 77 of which were submitted to

the planning authorities in the CA for approval. However, these efforts were to

no avail. By the end of 2015, only three had been approved, covering a total

area of 57 hectares (0.02% of Area C).

restricts Palestinian construction by seldom approving requests for building

permits, whether for housing, for agricultural or public uses, or for laying

infrastructure. The Civil Administration (CA) – the branch of the Israeli

military designated to handle civil matters in Area C – refuses to prepare

outline plans for the vast majority of Palestinian communities there. Until

September 2015, it had prepared and approved plans for just 16 of the 180

Palestinian communities located entirely within Area C. The approved plans span

less than 1% of Area C, and relate to land that has largely been built up

already. The plans were drawn up without consulting the communities and do not

meet international planning standards. Their boundaries run close to the

built-up areas of the villages, leaving out land for farming, grazing flocks

and future development. From 2010 to 2015, the Palestinian Authority prepared

108 outline plans for 116 communities in Area C, 77 of which were submitted to

the planning authorities in the CA for approval. However, these efforts were to

no avail. By the end of 2015, only three had been approved, covering a total

area of 57 hectares (0.02% of Area C).

The odds of a Palestinian receiving a building

permit in Area C – even on privately-owned land – are slim to nonexistent. CA

figures show that from 2010 to 2014, Palestinians applied for 2,020 building

permits, of which a mere 33 – or 1.5% – were approved. Given the futility of

the effort, many Palestinians forgo requesting a permit altogether. Without any

possibility of receiving a permit and building legally, the needs of a growing

population leave Palestinians no choice but to develop their communities and

build homes without permits. This, in turn, forces them to live under the

constant threat of seeing their homes and businesses demolished.

permit in Area C – even on privately-owned land – are slim to nonexistent. CA

figures show that from 2010 to 2014, Palestinians applied for 2,020 building

permits, of which a mere 33 – or 1.5% – were approved. Given the futility of

the effort, many Palestinians forgo requesting a permit altogether. Without any

possibility of receiving a permit and building legally, the needs of a growing

population leave Palestinians no choice but to develop their communities and

build homes without permits. This, in turn, forces them to live under the

constant threat of seeing their homes and businesses demolished.

The impact of this Israeli policy extends beyond

Area C, to the hundreds of Palestinians communities located entirely or

partially in Areas A and B, as the land reserves for many of these communities

lie in Area C and are subject to Israeli restrictions there.

Area C, to the hundreds of Palestinians communities located entirely or

partially in Areas A and B, as the land reserves for many of these communities

lie in Area C and are subject to Israeli restrictions there.

The demand for land for development has grown

considerably since the 1995 division of the West Bank: The Palestinian

population has nearly doubled, and the land reserves in Areas A and B have been

nearly exhausted. Due to the housing shortage, much land still available in

these areas is used for residential construction, even if it is more suited for

other uses, such as agriculture.

considerably since the 1995 division of the West Bank: The Palestinian

population has nearly doubled, and the land reserves in Areas A and B have been

nearly exhausted. Due to the housing shortage, much land still available in

these areas is used for residential construction, even if it is more suited for

other uses, such as agriculture.

Without land for construction, local Palestinian

authorities cannot supply public services that require new structures, such as

medical clinics and schools, nor can they plan open spaces for recreation

within communities. Realizing the economic potential of Area C – in branches

such as agriculture, quarrying for minerals and stone for construction,

industry, tourism and community development – is essential to the development

of the entire West Bank, including creating jobs and reducing poverty. Area C

is also vital for regional planning, including laying infrastructure and

connecting Palestinian communities throughout the West Bank.

authorities cannot supply public services that require new structures, such as

medical clinics and schools, nor can they plan open spaces for recreation

within communities. Realizing the economic potential of Area C – in branches

such as agriculture, quarrying for minerals and stone for construction,

industry, tourism and community development – is essential to the development

of the entire West Bank, including creating jobs and reducing poverty. Area C

is also vital for regional planning, including laying infrastructure and

connecting Palestinian communities throughout the West Bank.

In contrast to the restrictive planning for

Palestinian communities, Israeli settlements – all of which are located in Area

C – are allocated vast tracts of land, drawn up detailed plans, connected to

advanced infrastructure, and the authorities turn a blind eye to illegal

construction in them. Detailed, modern plans have been drawn up for the

settlements, including public areas, green zones and, often, spacious

residential areas. They enjoy a massive amount of land, including farmland that

can serve for future development.

Palestinian communities, Israeli settlements – all of which are located in Area

C – are allocated vast tracts of land, drawn up detailed plans, connected to

advanced infrastructure, and the authorities turn a blind eye to illegal

construction in them. Detailed, modern plans have been drawn up for the

settlements, including public areas, green zones and, often, spacious

residential areas. They enjoy a massive amount of land, including farmland that

can serve for future development.

Israel’s policy in Area C is based on the

assumption that the area is primarily meant to serve Israeli needs, and on the

ambition to annex large parts of it to the sovereign territory of Israel. To

that end, Israel works to strengthen its hold on Area C, to further exploit the

area’s resources and achieve a permanent situation in which Israeli settlements

thrive and Palestinian presence is negligible. In doing so, Israel has de facto

annexed Area C and created circumstances that will leverage its influence over

the final status of the area.

assumption that the area is primarily meant to serve Israeli needs, and on the

ambition to annex large parts of it to the sovereign territory of Israel. To

that end, Israel works to strengthen its hold on Area C, to further exploit the

area’s resources and achieve a permanent situation in which Israeli settlements

thrive and Palestinian presence is negligible. In doing so, Israel has de facto

annexed Area C and created circumstances that will leverage its influence over

the final status of the area.

Posted in Blog