about the Nakba in Israel today. History

is what the State says it is. The word ‘Nakba’

is officially banned from Israeli, including Israeli Arab, textbooks. By

banning a word, Israeli’s stupid leaders, led by Netanyahu, believe that

they can rewrite history itself. That Israel’s

Palestinians will somehow forget about what happened in 1948. What this is really about is removing

knowledge of the Nakba from Israeli Jewish history.

stupid Police state doesn’t reclassify files that have already been

declassified. The secrets are already

out. They have already been

studied. What kind of mentality is it

that believes that by reclosing the archives you can change or rewrite history?

mentality that can rewrite the history of the holocaust and pretend that it was

the Palestinians not Hitler who was responsible – step forward Netanyahu!

state archives

that have already been cited in history books are being re-classified in the

State Archives.

|

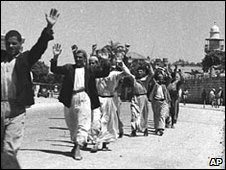

| Israeli troops in Gaza in 1957 when a number of massacres of civilians took place before Israel withdrew – all excised from official memory |

Israeli

state archive documents that were de-classified in the 1980s have been

re-classified in recent years, according to a recently hired assistant

professor at the University of Maryland’s Center for Jewish Studies.

|

| Palestinian refugees fleeing to Lebanon in 1948 |

Hazkani, who was Israel Channel 10′s military correspondent from 2004-8 and

will soon complete his doctorate at New York University, discusses the

background and politics of the state’s decision to re-classify various

documents in an interview

for the Ottoman History Podcast.

the interview, which was recorded in July 2014 (I came across it recently by

chance), Hazkani estimates that about one-third of documents that were

de-classified in the 1980s have been re-classified starting from the late

1990s, when the archives were digitized.

reclassified documents were used extensively by prominent “new historians” like

Benny Morris (“Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem”), Avi Shlaim (“The

Iron Wall”), Hillel Cohen (“Good Arabs” and “1929″) and Ilan Pappe (“Ethnic

Cleansing of Palestine”) and cited in their books.

even though these books certainly exist in the public domain, and they do cite

original documents in the Israeli state archives that note orders given to the

nascent Israeli army to expel Palestinians during the 1948 war, the government

of Israel continues to promote its official narrative — that the Palestinians

left of their own accord. Hence the government and, more specifically, the

security establishment attempts to control the discourse by re-classifying these

documents.

25-minute interview is embedded below and well worth your time. Among other

things, Hazkani explains that Israel adopted a law in 1955 that specified

documents could be kept classified for a maximum of 50 years. But the Mossad,

the army and the Shin Bet, which control very large archives, refused to comply

with the law. Petitions to declassify specific documents have been brought

before the higher courts, with some pending now.

the end of the interview, Hazkani recounts a fascinating anecdote involving his

own experience with re-classified documents, this time connected with an

incident reported by Joe Sacco in his graphic novel “Footnotes

in Gaza.” Sacco traveled to Gaza in 2002 and 2003 to research the

book, which was published in 2009. The “footnote” refers to an incident that

occurred during the Israeli army’s three-month occupation of Gaza during

1956-7, during the Suez War.

the book, Sacco interviews several Palestinian eyewitnesses who describe having

seen the Israeli army shoot and kill at least 100 civilians out of the hundreds

that were rounded up and herded into a schoolyard in Rafah. According to the

witnesses, the event took place on November 12, 1956. The details, as drawn and

described in Sacco’s book, are quite harrowing, which explains why articles

about the book published in Haaretz caused a furore. In the podcast, Hazkani

recounts having followed the online discussions and debates about the claims in

Sacco’s book.

blogger, recounts Hazkani, writes in a post about having seen a specific

document that confirms some of Sacco’s account. Hazkani happened to be on his

way to the archive when he read that post; and since the blogger cited a

specific file number, he asked to see it. But when he received the file, it

contained a note that indicated the document had been reclassified the previous

day — the same day the blogger had published his post.

is obviously an inherent contradiction in Israeli authorities so clumsily

trying to reclassify damning documents that have already been cited by well-known

historians, even as it invests so much money and effort in promoting its image

abroad as a transparent democracy. Israel is obviously not the only country

that tries to shape its image by keeping documents classified for extended

periods or even indefinitely. Hazkani mentions colonial archives recently

uncovered in Britain, and Turkey’s still-classified archives from the Ottoman

era. But Israel’s attempts to redact or classify documents after they have been

extensively cited seems counter-productive at best.

1948 no catastrophe says Israel, as term nakba banned from Arab children’s textbooks

Israel’s education ministry has ordered the removal of the word nakba

– Arabic for the “catastrophe” of the 1948 war – from a school

textbook for young Arab children, it has been announced.

The decision – which will alter books aimed at eight- and nine-year-old Arab

pupils – will be seen as a blunt assertion by Binyamin Netanyahu’s Likud-led

government of Israel’s historical narrative over the Palestinian one.

The term nakba has a similar resonance

for Palestinians as the Hebrew word shoah –

normally used to describe the Nazi Holocaust – does for Israelis and Jews. Its

inclusion in a book for the children of Arabs, who make up about a fifth of the

Israeli population, drives at the heart of a polarised debate over what

Israelis call their “war of independence”: the 1948 conflict which

secured the Jewish state after the British left Palestine, and led to the

flight of 700,000 Palestinians, most of whom became refugees.

Netanyahu spoke for many Jewish Israelis two years ago when he argued that

using the word nakba in Arab schools was

tantamount to spreading propaganda against Israel.

“ethnic cleansing”. But in recent years a new generation of

revisionist Israeli historians has rejected the old official narrative that the

Palestinians, supported by the neighbouring Arab states, were responsible for

their own misfortune.

Reflecting those changing perceptions, Ehud Olmert, Israel’s last prime

minister and leader of the centrist Kadima party, referred to Palestinian

“suffering” at the Annapolis peace conference in 2007.

Netanyahu’s Likud takes a different view. “There is no reason to

present the creation of the Israeli state as a catastrophe in an official

teaching programme,” said the education minister, Gideon Saar.

“The

objective of the education system is not to deny the legitimacy of our state,

nor promote extremism among Arab-Israelis.” There was bitter controversy

in 2007 when nakba was introduced into a

book for use in Arab schools only, by the then education minister, Yuli Tamir

of the centre-left Labour party.

“In no country in the world does an educational curriculum refer to the

creation of the country as a ‘catastrophe’,” Saar told MPs in the Knesset

yesterday. “There is a difference between referring to specific tragedies

that take place in a war – either against the Jewish or Arab population – as

catastrophes, and referring to the creation of the state as a

catastrophe.”

Arab MP Hana Sweid accused the government of “nakba

denial”. The follow-up committee for Arab education said:

“Palestinian-Arab society in Israel has every right to preserve its

collective memory, including in its school curriculums.”

Jafar Farrah, director of Mossawa (Equality), an Israeli-Arab advocacy

group, told Reuters the decision to excise the term nakba only

“complicated the conflict”. He called it an attempt to distort the

truth and seek confrontation with the country’s Arab population.

Yossi Sarid, a dovish former education minister, said the decision showed

insecurity. “Zionism has already won in many ways, and can afford to be

more confident,” he said. “We need not be afraid of a word.”

Israeli Arab activists have also pledged to carry on marking Nakba Day in

the face of planned legislation that would withhold government money from

institutions that fund activity deemed detrimental to the state.

These include commemorating the nakba – on

the same day as Independence Day – “rejecting Israel’s existence as the

state of the Jewish people” and supporting an “armed struggle or

terrorist acts” against Israel. An initial version proposed by the

far-right foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman would have banned all Nakba

commemorations and carried sentences of up to three years in prison.

By the book

Japan has long been criticised for toning down aspects of

its wartime atrocities in textbooks, particularly the Nanjing massacre and use

of sex slaves. Russia has taken up Soviet techniques of

airbrushing history, a book being banned two years ago for positing that

Vladimir Putin had established an “authoritarian dictatorship”. A

decade after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, black schoolchildren in South

Africa were still studying textbooks that extolled the voortrekkers

and offered only minimal explanations of their own history. In Britain

it was an exam paper that caused offence when a poem by Carol Ann Duffy

containing referencing knife crime was removed from the GCSE syllabus. The

Carol Ann Duffy poem began: “Today I am going to kill something.

Anything./ I have had enough of being ignored and today/ I am going to play

God.”