There is a

widespread belief that because Iran is or was in conflict with the United

States and because of the hostility of Netanyahu and the Israeli state, it is

therefore a progressive state. The

article below on the brutal repression of the Iranian Kurds shows that the

Iranian state is one of the most repressive in the world.

state itself, with the use of the Basij, the

paramilitary wing of the Revolutionary Guards, and the penetration of its

agents into every level of society best resembles both the Stalinist use of the

secret police, for example the Stasi and Hitler’s use of Nazi party spies and

watchers at every level of society.

1,000 people a year, dwarfing even Saudi Arabia and second only to China. Its method of execution, which is hanging

from cranes, is more akin to slow strangulation and therefore particularly

barbaric.

|

| Sanandaj is the main stage of the young Shiite regime’s massive counterinsurgency against progressive Kurdish aspirations. (Photo: Airin Bahmani) |

beckoning with the end of sanctions, is quite willing to avert its eyes from

the repression of the regime because the West’s conflict with Iran was never

about human rights (although it was a useful pretext). Trade always oils human rights abuses and

Iran is no exception. There are

differences between Saudi Arabia and Iran, not least in the vigorous civil

society in the latter, which is more testament to the populace and the legacy

of secularism rather than the brutal rule of the Islamic clerics. Likewise women are in a stronger position in

Iran compared to Saudi Arabia.

always support Iran against Israel, which is the main arm of imperialism in the

Middle East, this should not mean that we support the Islamic state of Iran

when it comes to the Kurds or its own people.

Iran’s Kurdish Leftists Share Experience of Post-Revolution State Repression

A view of the city of Sanandaj, the center of Kurdish life in Iran, marks

the end of a hectic, eight-hour-long bus trip. The shuttle zigzags higher up,

affording a rugged view of one of Iran’s northwestern mountain ranges and a

stunning valley where Sanandaj is located.

At the city border, there is a checkpoint operated by the Revolutionary

Guards. This is the first contact with state officials during the more than

500-kilometer journey from the Iranian capital of Tehran to the unofficial

Kurdish capital. Iranian authorities inspect and keep record of all vehicles to

and from Sanandaj. After armed officials of the Revolutionary Guards have

searched our shuttle, we are permitted to continue to the city.

|

| Sanandaj is the main stage of the young Shiite regime’s massive counterinsurgency against progressive Kurdish aspirations. (Photo: Airin Bahmani) |

High walls rise in Sanandaj, extend for many kilometers and enclose vast

areas, forming a number of closed zones within the city. “State officials,

including personnel of the enormous security apparatus, have their own shops,

schools, hospitals, swimming pools and gyms. They have small cities inside

Sanandaj,” according to Bahar, an Iranian Kurdish woman in her 50s who has

been deeply involved in Kurdish left-wing politics before, during and after the

Iranian revolution. “Government employees live a well-off, sheltered life

behind their walls and fences.”

In Iran, the Revolutionary Guards, institutionally separated from the

military, preserve the country’s politico-religious system of

government. Following the Iranian Constitution, the Revolutionary Guards

enforce the Shiite norms of the Islamic Republic. Basij, the paramilitary

subdivision of the Revolutionary Guards, serves as a national intelligence

network and imposes adherence to the state’s moral code.

The Iranian government recruits citizens to Basij from nearly all spheres of

Iranian society. According to a conservative estimate, the number of Iranians

who belong to the Basij system is in the millions. During peacetime, Basij’s duties include

gathering intelligence on the political views of private citizens and

communities and providing that information to the relevant state organs.

Among Iranian left-leaning dissidents and organizers, Basij is known for

apprehending and subduing critical political activists. Bahar describes Basij

as the eyes and ears of the government. “The efficacy of the institution

is based on its gigantic size as it aggressively operates and recruits in

comprehensive schools, associations and institutions – both government and

privately owned – and at university level.

“Anyone can be a Basiji. It is not a rare occurrence that a Basiji hides his or her state affiliations from family and relatives,” Bahar said.

The perks and benefits that Basij collaboration entails are considerable and

enticing to many citizens who might otherwise not harbor deep-seated sympathies

or loyalties to the Shiite leadership.

The perks include monetary bonuses, housing benefits and

food stamps. Senior high school students joining Basij may be rewarded with

scholarships to prestigious universities. It is likely that US-driven sanctions against

Iran used to make these carrots ever more tempting. In a survey conducted in Tehran, 55.4 percent of Basij

members were working class and 43.4 percent were lower middle class.

Furthermore, official Iranian sources confirm that 62 percent of Iranians regard the

multiple benefits offered by the state to Basij members to be the primary

motive behind citizens’ interest to join the organization.

|

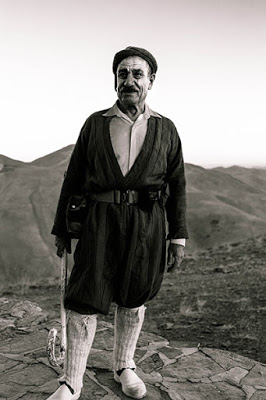

| Roja’s son was executed by the state as part of the suppression of the uprising. (Photo: Airin Bahmani) |

Quelling the Progressive Iranian Kurdish Uprising

The atmosphere of suspiciousness and cautiousness instigated by Basij has a

decades-long history, not least in the Kurdish areas of the country. For

Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamist cadre, which had just spearheaded a revolution,

arguably the gravest and most immediate domestic challenge emerged from

northwestern Iran in the form of a progressive, democratic and pluralistic

Kurdish grassroots uprising.

During and after the Iranian revolution, the most powerful Kurdish political

groupings were the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (KDPI) and the Komala.

The KDPI advocated for a center-left platform and sought to secure Kurdish

autonomy from Khomeini. Already in April 1979, the KDPI presented the government an elaborate deal in which Tehran

would take the lead in matters of defense, foreign relations and long-term

economic planning. In return, the central government would allow the

establishment of an autonomous Kurdistan with its own parliament, which would

exercise far-reaching legislative powers. In the KDPI’s proposal, Kurdish was

to be recognized as an official language along with Persian.

Partly in agreement with the KDPI’s autonomy model, the Komala

platform revolved around an emphasis on agrarian reform, workers’

and women’s rights and the importance of diminishing the clout of tribal

chieftains. Initially a Marxist and feminist underground established in the

late 1960s, the Komala gained immense popularity among Iranian Kurds soon after

the revolution. The Komala enjoyed vast support among the country’s Kurdish

population and had its most prominent strongholds in Sanandaj, Marivan and

Baneh – all significant Kurdish cities in close proximity to one another.

“Fostering democratic process with a strong emphasis on a feminist and

pluralistic platform was among the primary aims of our insurrection,”

Bahar said.

Although a solid majority of Iranian Kurds had supported the revolution, no

consensus was reached between any Kurdish organizations and Khomeini on the

future status of Iranian Kurdistan. Soon, fighting erupted between government

forces and Kurdish fighters. The ensuing confrontation between the Shiite

triumphalists and Kurdish political movements was to be a showcase not only for

the Revolutionary Guards and its paramilitary Basij, but for the entire

Islamist enterprise.

Of the numerous Iranian Kurdish cities, Sanandaj swiftly emerged not only as

the center of left-oriented Kurdish popular uprising, but the main stage of the

armed conflict. Exuding confidence in its ability to comprehensively

reconfigure the post-Shah Iranian state at a rapid pace, the Shiite elite

launched a full-scale counterinsurgency. Kurdish cities became targets of a heavy bombing campaign as the Islamists fired shells

from state installations within those cities. Tehran also deployed its air

force against the Kurdish rebellion.

Ultimately, incursion by the Revolutionary Guards and Basij paramilitaries

into Iran’s Kurdish cities, particularly Sanandaj, proved an epoch-making event

in the counterinsurgency. The Revolutionary Guards quickly smashed the armed

wing of the revolt. State forces began searching houses one by one, hunting

down the architects of the insurgency.

After resorting to a large-scale program of torture, interrogation and

blackmail, the Iranian authorities managed to chart the structure and plans of

the rebellion. Between 1979 and 1982, the Iranian government killed approximately 10,000 Kurds – a considerable

portion in mass executions.Lasting Emotional and Physical Trauma

Every single eyewitness interviewee of ours, including Bahar, recollects how

the state delivered death sentences in the style of an assembly line. A

preponderance of the death sentences was issued by the judge Ayatollah Sadiq

Khalkhali, who earned the nickname the “Hanging Judge.” Our

interviewees stressed the personal role of Khalkhali in subduing the uprising.

When Khalkhali died in 2003, his legacy was praised in the Iranian

Parliament. Speaker of the Parliament Mehdi Karoubi paid tribute, in particular, to Khalkhali’s performance in

the early phases of the revolution.

“We were all waiting for our turn,” Bahar said. “Participants

in the uprising were being arbitrarily executed. State forces inflicted the

most cold-blooded torture techniques on us, making sure that those of us who

they preferred alive did not die.“

Bahar was released after a year in custody. Most of her family members were

either summarily executed or managed to flee the country.

“Later, we got back the body of our cousin Reza, a member of the

Komala,” Bahar said. “His torso was full of burns, contusions and

bruises. A large emblem of Iran, the crescent and a sword, was burned to his

rib cage. Reza was far from the only member of my family who was tortured to

death.”

Later, the Revolutionary Guards destroyed Reza’s grave, alongside the graves

of all other known political activists and prisoners. It was inconceivable for

the authorities to allow any indication of a political status of those buried

in the main cemetery in Sanandaj. Furthermore, they did not tolerate the

gravestones to be inscribed with the names of the deceased if they had any

affiliations with the uprising.

After the early phases of the uprising, the authorities stopped delivering

the bodies of Kurdish activists back to their families. “All we have left

of Reza is his memory and a location he was buried in,” Bahar said.

It is not just through the experiences of her family members and friends

that Bahar is familiar with the details of the state’s counterinsurgency

campaign. In 1983, she was arrested by the Revolutionary Guards.

“We were taken to an interrogation room one by one. When it was my

turn, they blindfolded me and brought me into the room. There were a number of

interrogators and officers present. They forced me to lie down on my stomach

and tied me to a metal bed. I was bombarded with questions on my political

activities, my motives, my comrades and their whereabouts. My answers did not

appeal to the interrogators. They began lashing the soles of my feet with power

cables. This happened continuously, day after day, until I was unable to walk.

If I wanted to move, I had to crawl. The interrogators brought me a wheelchair.

Then the foot whipping continued.”

In its crackdown on the uprising, the Iranian government routinely resorted

to lethal torture as well as torture that caused permanent damage. “The

pain inflicted on many of us was so severe that it will stay with us for the

rest of our lives. Presently, in 2015, I can still feel it every single day.

Bastinado [foot whipping] led to neuralgia. According to a doctor, nerve

pathways in my feet have been damaged and will never heal.”

Bahar shared in great detail how she and all of her comrades gave it their

all, as she put it, “to finally emancipate [Iran] from the yoke of

authoritarianism … [which the nation] had witnessed since the ousting of

Mohammed Mossadegh in 1953.”

The organizers of the uprising will carry with them the defeat they suffered

for the rest of their lives. “We longed for a social and political change

and were ready to risk everything to attain it,” Bahar said.

“Notwithstanding our best efforts, we did not succeed. What we were left

with is lasting emotional and physical trauma.”

Roja, an 84-year-old woman of Kurdish descent whose nine children all

participated in the uprising as members of the Komala, digs up a photo album of

her son who was executed in Sanandaj in 1982. It is prohibited to engage in any

commemoration of those killed in the suppression of the uprising, hence

documents such as photos must be hidden. As routine practice, Revolutionary

Guards deploy officers to put an end to all forms of organized commemoration.

Looking at photos of her son, Roja commented on the political trajectory of

Iran after the Shah. Roja, who has lived under the rule of Reza Shah, Mohammed

Mossadegh, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and now the Islamists, observed that

never in her lifetime “has there been such a long period marked by a lack

of momentum in Kurdish popular-based progressive politics as after the quelling

of the uprising in the early 1980s. The state reached its goal of completely

annihilating Kurdish leftism.”

That every single one of our 24 interviewees can list countless people from

their circle of acquaintances who were either executed or severely tortured

suggests the scope and brutality of Tehran’s counterinsurgency.

A most salient conclusion to be drawn from our interviews with organizers of

and participants in the uprising is that the Shiite republic ultimately

succeeded in completing something in which even the Shah and his secret police,

the Savak, had failed: obliterating the socialist and progressive political

momentum among the Iranian Kurds.

Airin Bahmani

Airin Bahmani is an Iranian Kurdish political commentator specializing in

the domestic and foreign policies of Iran. She is regularly featured in the

Finnish media as a pundit on Islamophobia, Kurdish politics, feminism and the

Islamic State. She majors in Middle Eastern studies at the University of

Helsinki.

Bruno Jäntti

Bruno Jäntti is an investigative journalist specializing in international

affairs. He is a contributor to Al Jazeera, Le Monde Diplomatique and a number

of Finnish newspapers and magazines. He focuses on Middle Eastern political

processes and has worked extensively in the region, including Northern and

Southern Kurdistan.

Related Stories

Release