I first intended to publish this article from the New York Times on international women’s day

about a largely unknown Black journalist.

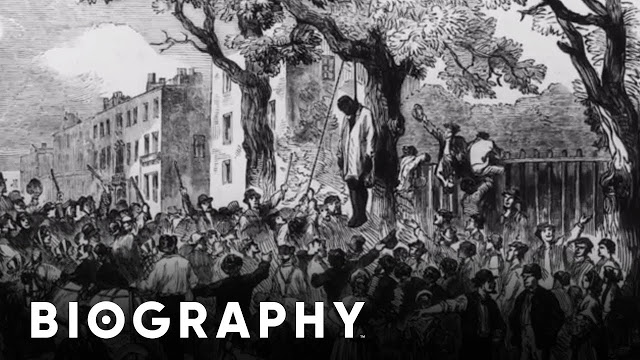

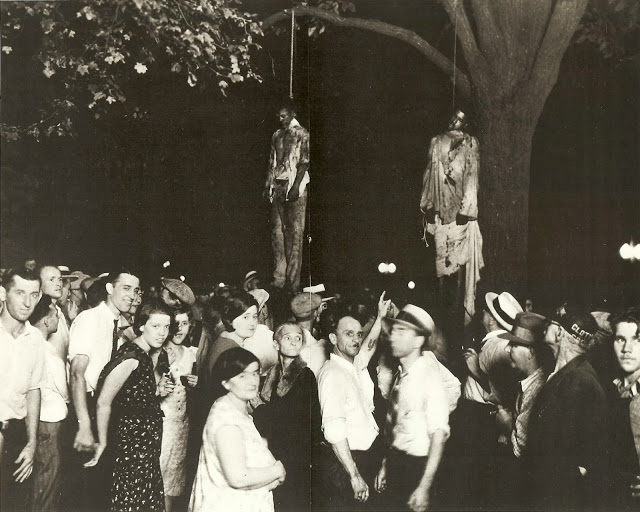

However it is as appropriate now as it was then. I apologise if people find the graphic

disturbing however it is important that people understand the nature of racism

in the United States until recently.

When we contrast this with the false and fake ‘anti-Semitism’ campaign

in the Labour Party then people should be rightly angry.

Tony Greenstein

By CAITLIN DICKERSON

|

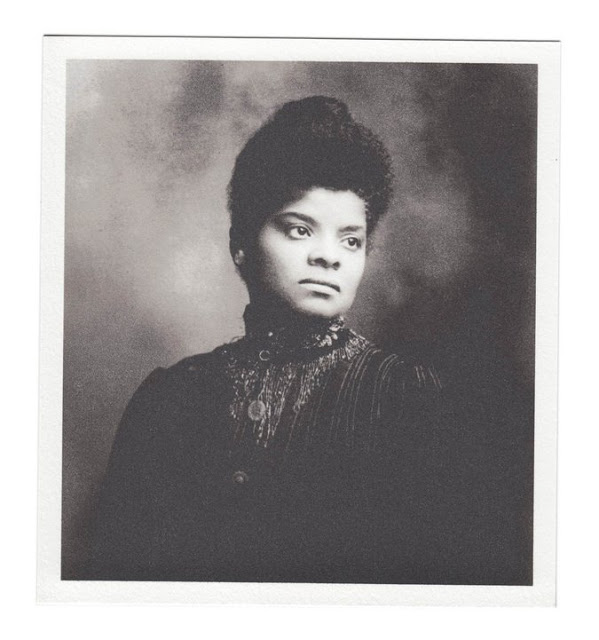

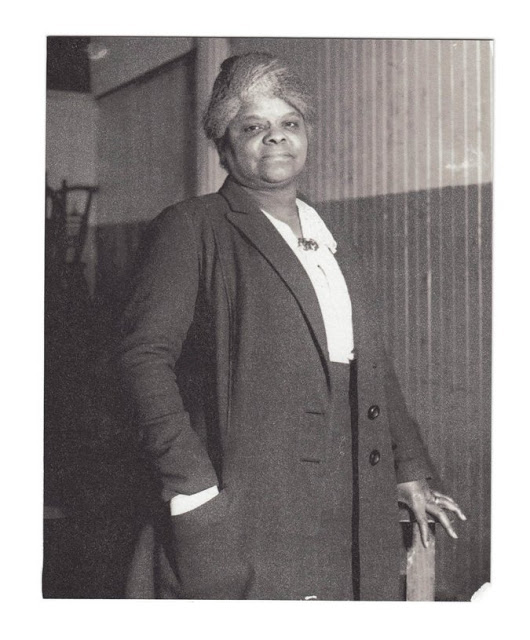

Ida B. Wells, one of the nation’s most influential investigative reporters, in 1920. Chicago History Museum/Getty Images

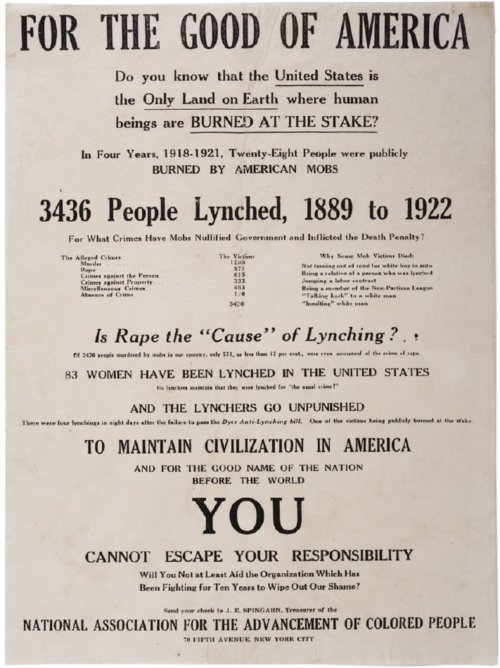

It was not all that unusual when, in 1892, a mob dragged Thomas Moss out

of a Memphis jail in his pyjamas and shot him to death over a feud that began

with a game of marbles. But his lynching changed history because of its effect

on one of the nation’s most influential journalists, who was also the godmother

of his first child: Ida B. Wells.

of a Memphis jail in his pyjamas and shot him to death over a feud that began

with a game of marbles. But his lynching changed history because of its effect

on one of the nation’s most influential journalists, who was also the godmother

of his first child: Ida B. Wells.

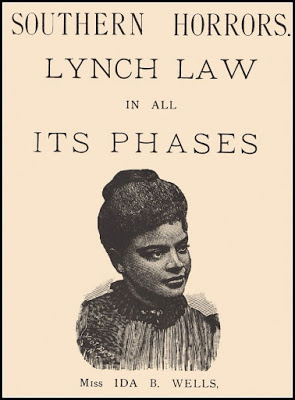

“It is with

no pleasure that I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed,” Wells wrote

in 1892 in the introduction to “Southern Horrors,” one of her seminal works

about lynching, “Somebody must show that

the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to

have fallen upon me to do so.”

no pleasure that I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed,” Wells wrote

in 1892 in the introduction to “Southern Horrors,” one of her seminal works

about lynching, “Somebody must show that

the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to

have fallen upon me to do so.”

Wells is considered by historians to have been the most famous black

woman in the United States during her lifetime, even as she was dogged by

prejudice, a disease infecting Americans from coast to coast.

woman in the United States during her lifetime, even as she was dogged by

prejudice, a disease infecting Americans from coast to coast.

She pioneered reporting techniques that remain central tenets of modern

journalism. And as a former slave who stood less than five feet tall, she took

on structural racism more than half a century before her strategies were

repurposed, often without crediting her, during the 1960s civil rights

movement.

journalism. And as a former slave who stood less than five feet tall, she took

on structural racism more than half a century before her strategies were

repurposed, often without crediting her, during the 1960s civil rights

movement.

Wells was already a 30-year-old newspaper editor living in Memphis when

she began her anti-lynching campaign, the work for which she is most famous.

After Moss was killed, she set out on a reporting mission, crisscrossing the

South over several months as she conducted eyewitness interviews and dug up

records on dozens of similar cases.

she began her anti-lynching campaign, the work for which she is most famous.

After Moss was killed, she set out on a reporting mission, crisscrossing the

South over several months as she conducted eyewitness interviews and dug up

records on dozens of similar cases.

Her goal was to question a stereotype that was often used to justify

lynchings — that black men were rapists. Instead, she found that in two-thirds

of mob murders, rape was never an accusation. And she often found evidence of

what had actually been a consensual interracial relationship.

lynchings — that black men were rapists. Instead, she found that in two-thirds

of mob murders, rape was never an accusation. And she often found evidence of

what had actually been a consensual interracial relationship.

She published her findings in a series of fiery editorials in the

newspaper she co-owned and edited, The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight. The

public, it turned out, was starved for her stories and devoured them

voraciously. The Journalist, a mainstream trade publication that covered the

media, named her “The Princess of the Press.”

newspaper she co-owned and edited, The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight. The

public, it turned out, was starved for her stories and devoured them

voraciously. The Journalist, a mainstream trade publication that covered the

media, named her “The Princess of the Press.”

Readers of her work were drawn in by her fine-tooth reporting methods

and language that, even by today’s standards, was aberrantly bold.

and language that, even by today’s standards, was aberrantly bold.

Wells wrote

about the victims of racist violence and organized economic boycotts long

before the tactic was popularized.

about the victims of racist violence and organized economic boycotts long

before the tactic was popularized.

“There has been

no word equal to it in convincing power,”

no word equal to it in convincing power,”

Frederick Douglass wrote to her in a letter that

hatched their friendship. “I have spoken,

but my word is feeble in comparison,” he added.

hatched their friendship. “I have spoken,

but my word is feeble in comparison,” he added.

He was referring to writing like the kind that she published in The Free

Speech in May 1892.

Speech in May 1892.

“Nobody in

this section of the country believes the threadbare old lie that Negro men rape

white women,” Wells wrote.

this section of the country believes the threadbare old lie that Negro men rape

white women,” Wells wrote.

Instead, Wells saw lynching as a violent form of subjugation — “an excuse to get rid of Negroes who were

acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized and ‘the nigger

down,’ ” she wrote in a journal.

acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized and ‘the nigger

down,’ ” she wrote in a journal.

Wells was born into slavery in Holly Springs, Miss., in 1862, less than

a year before Emancipation. She grew up during Reconstruction, the period when

black men, including her father, were able to vote, ushering black

representatives into state legislatures across the South. One of eight

siblings, she often tagged along to Bible school on her mother’s hip.

a year before Emancipation. She grew up during Reconstruction, the period when

black men, including her father, were able to vote, ushering black

representatives into state legislatures across the South. One of eight

siblings, she often tagged along to Bible school on her mother’s hip.

In 1878, her parents both died of yellow fever, along with one of her

brothers; and at 16, she took on caring for the rest of her siblings. She

supported them by working as a teacher after dropping out of high school and

lying about her age. She finished her own education at night and on weekends.

brothers; and at 16, she took on caring for the rest of her siblings. She

supported them by working as a teacher after dropping out of high school and

lying about her age. She finished her own education at night and on weekends.

Around the same time, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was largely nullified

by the Supreme Court, reversing many of the advancements of Reconstruction. The

anti-black sentiment that grew around her was ultimately codified into Jim

Crow.

by the Supreme Court, reversing many of the advancements of Reconstruction. The

anti-black sentiment that grew around her was ultimately codified into Jim

Crow.

“It felt

like a dramatic whiplash,” said Troy Duster, Wells’s grandson, who is a

sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and New York

University. “She cuts her teeth

politically in this time of justice, justice, justice, and then injustice.”

like a dramatic whiplash,” said Troy Duster, Wells’s grandson, who is a

sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and New York

University. “She cuts her teeth

politically in this time of justice, justice, justice, and then injustice.”

Observing the changes around her, Wells decided to become a journalist

during what was a golden era for black writers and editors. Her goal was to

write about black people for black people, in a way that was accessible to

those who, like her, were born the property of white owners and had much to

defend.

during what was a golden era for black writers and editors. Her goal was to

write about black people for black people, in a way that was accessible to

those who, like her, were born the property of white owners and had much to

defend.

Her articles were often reprinted abroad, as well as in the more than

200 black weeklies then in circulation in the United States.

200 black weeklies then in circulation in the United States.

Whenever possible, Wells named the victims of racist violence and told

their stories. In her journals, she lamented that her subjects would have

otherwise been forgotten by all “save the

night wind, no memorial service to bemoan their sad and horrible fate.”

their stories. In her journals, she lamented that her subjects would have

otherwise been forgotten by all “save the

night wind, no memorial service to bemoan their sad and horrible fate.”

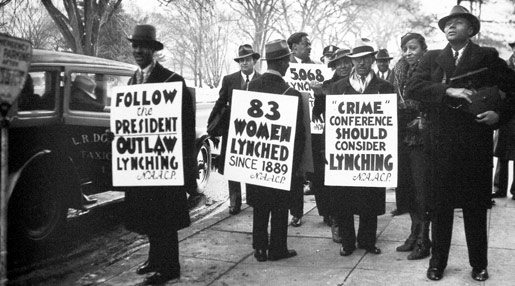

Wells also organized economic boycotts long before the tactic was

popularized by other, mostly male, civil rights activists, who are often

credited with its success.

popularized by other, mostly male, civil rights activists, who are often

credited with its success.

In 1883, she was forced off a train car reserved for white women. She

sued the railroad and lost on appeal before the Tennessee Supreme Court, after

which she urged African-Americans to avoid the trains, and later, to leave the

South entirely. She also travelled to Britain to rally her cause, encouraging

the British to stop purchasing American cotton and angering many white Southern

business owners.

sued the railroad and lost on appeal before the Tennessee Supreme Court, after

which she urged African-Americans to avoid the trains, and later, to leave the

South entirely. She also travelled to Britain to rally her cause, encouraging

the British to stop purchasing American cotton and angering many white Southern

business owners.

Wells was as fierce in conversation as she was in her writing, which

made it difficult for her to maintain close relationships, according to her

family. She criticized people, including friends and allies, whom she saw as

weak in their commitment to the causes she cared about.

made it difficult for her to maintain close relationships, according to her

family. She criticized people, including friends and allies, whom she saw as

weak in their commitment to the causes she cared about.

“She didn’t suffer

fools and she saw fools everywhere,” Duster, her grandson, said.

fools and she saw fools everywhere,” Duster, her grandson, said.

One exception was her husband and closest confidant, Ferdinand L.

Barnett, a widower who was a lawyer and civil rights activist in Chicago. After

they married in

1895, Barnett’s activism took a back seat to his wife’s career. Theirs was

an atypically modern relationship: He cooked dinner for their children most

nights, and he cared for them while she traveled to make speeches and organize.

Barnett, a widower who was a lawyer and civil rights activist in Chicago. After

they married in

1895, Barnett’s activism took a back seat to his wife’s career. Theirs was

an atypically modern relationship: He cooked dinner for their children most

nights, and he cared for them while she traveled to make speeches and organize.

Later in life, Wells fell from prominence as she was replaced by

activists like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, who were more

conservative in their tactics, and thus had more support from the white and

black establishments. She helped to found prominent civil rights organizations

including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and

the National Association of Colored Women, only to be edged out of their

leadership.

activists like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, who were more

conservative in their tactics, and thus had more support from the white and

black establishments. She helped to found prominent civil rights organizations

including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and

the National Association of Colored Women, only to be edged out of their

leadership.

During the final years of her life, living in Chicago, Wells ran for the

Illinois State Senate, but lost abysmally. Despite her ebbing influence, she

continued to organize around causes such as mass incarceration, working for

several years as a probation officer, until she died of kidney

disease on March 25, 1931, at 68.

Illinois State Senate, but lost abysmally. Despite her ebbing influence, she

continued to organize around causes such as mass incarceration, working for

several years as a probation officer, until she died of kidney

disease on March 25, 1931, at 68.

Wells was threatened physically and rhetorically constantly throughout

her career; she was called a harlot and a courtesan for her frankness about

interracial sex. After her anti-lynching editorials were published in The Free

Speech, she was run out of the South — her newspaper ransacked and her life

threatened. But her commitment to chronicling the experience of

African-Americans in order to demonstrate their humanity remained unflinching.

her career; she was called a harlot and a courtesan for her frankness about

interracial sex. After her anti-lynching editorials were published in The Free

Speech, she was run out of the South — her newspaper ransacked and her life

threatened. But her commitment to chronicling the experience of

African-Americans in order to demonstrate their humanity remained unflinching.

“If this

work can contribute in any way toward proving this, and at the same time arouse

the conscience of the American people to demand for justice to every citizen,

and punishment by law for the lawless, I shall feel I have done my race a

service,” she wrote after fleeing Memphis, “Other

considerations are minor.”

work can contribute in any way toward proving this, and at the same time arouse

the conscience of the American people to demand for justice to every citizen,

and punishment by law for the lawless, I shall feel I have done my race a

service,” she wrote after fleeing Memphis, “Other

considerations are minor.”

Correction March 9, 2018

An earlier version of this article referred imprecisely to voting rights

during Reconstruction. Black men were able to vote. Women did not get the right

to vote until 1920.

during Reconstruction. Black men were able to vote. Women did not get the right

to vote until 1920.

Caitlin Dickerson is a national immigration reporter. More than a

century later, she still uses the reporting techniques that were pioneered by

Ida B. Wells.

century later, she still uses the reporting techniques that were pioneered by

Ida B. Wells.

Posted in Blog