Israel’s Palestinians Confined to a ‘Citizenship’ that is Meaningless

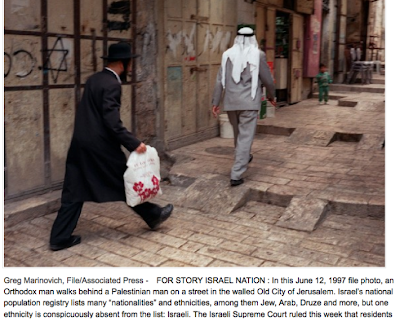

|

| Uzzi Ornan displays his ID card – which unlike a passport does not have any mention of an Israeli nationality. |

The Israel’s Supreme Court recently rejected a claim that there was an Israeli nationality. The claim was brought by Uzzi Ornan, a 90-year-old linguistics processor at the Technion, Tel Aviv. An Israeli nationality would undermine the ‘Jewish’ nature of the Israeli state.

The judgment reinforces the decision in a similar case was brought by George Tamarin in 1970. In the Tamarin case the Supreme Court, presided over by Justice Agranat held that ‘the desire to create an Israeli nation separate from the Jewish nation is not a legitimate aspiration.’

|

| Hebron settlers protected an army that gives Palestinians no protection |

It is a very strange State where it is held to be ‘illegitimate’ to want citizenship and nationality to be one and the same. That is the basis of all western democracies and the bourgeois revolutions.

Agranat pointed out that a division of the population into Israeli and Jewish nations would create a schism among the Jewish people and negate the foundation on which the State of Israel was established. The court ruling specified, “There is no Israeli nation separate from the Jewish People. The Jewish People is composed not only of those residing in Israel but also of Diaspora Jewry.”

Jewish Nationality Status as the Basis for Institutionalised Racial Discrimination in Israel

In Ornan the court explained that creating an Israeli nationality would have “weighty implications” on the state of Israel and could pose a danger to Israel’s founding principle: to be a Jewish state for the Jewish people.

Israel is the only state in the world which is a state, not of its own citizens, but of people residing anywhere in the world who are Jewish. The only comparison is Nazi Germany which in 1935 stripped German Jews of their nationality. Henceforth they were not Germans of the Jewish faith but Jews who were German subjects. The German Volk/people extended to all Germans, wherever they resided, and that was the basis for the attack on Czechoslovakia – the Sudetan Germans were claimed by Hitler as part of the German Vok. Poles and Jews were expelled from the annexed territories of Poland, in particular the Warthegau, and German residents of Poland and the Eastern Territories were brought in to settle the land.

|

| An ultra orthodox boy watches Sheik Jarrah protest against land confiscation in Jerusalem. Jewish nationals never have their land confiscated. |

The question of what constitutes a Jewish or Israeli identity has been a permanent dilemma for Israelis and non-Israelis alike. The definition of ‘who is a Jew’ is defined in Israel by Orthodox Jewry, i.e. someone born of a Jewish mother who has not adopted another religion. It is much the same as the Nazi definition in the Nuremberg Laws 1935, i.e. based on ethnicity or race.

British journalist Jonathan Cook, who resides in Nazareth, wrote an article Court nixes push for ‘Israeli nationality’ 18.10.13 Al-Jazeera. There is little to disagree with in the article but Moshe Machover, a co-founder of Matzpen, the Socialist Organisation in Israel has responded with a piece ‘ ‘Confusion Compounded’. However Moshe confuses the debate even further with an exploration of nationality and citizenship in European countries as well as Israel. I have written a response below. Moshe’s argument is written in the context of his belief that Israeli Jews or Hebrews are a separate nation, with which I disagree.

|

| Israel’s flag is based on Jewish religious symbols – it deliberately excludes non-Jews from feeling any attachment to the flag of the setters |

|

| All Israelis are Israeli nationals abroad! |

|

| Only on an Israeli passport is there an Israeli nationality |

“Zionist myths: Hebrew versus Jewish identity” also posted on:

Response to Moshe Machover on the question of Jewish citizenship and nationality

TG: In Britain and most European countries, citizenship and nationality are one and the same, certainly in terms of their practical effects. They might not recognise what is termed ‘national identity’ but that is the price of the nation state. In Britain, there is a debate over whether people are British nationals or English/ Welsh, Scottish. In any event it is immaterial, because no practical consequences flow from this.

MM: This is patently untrue. In several important respects the UK is a multi-national state. Wales has its own national assembly; Scotland has not only its own national assembly with considerable powers, but also its own legal and educational system. And let us not get into a discussion of Northern Ireland…

TG: In terms of rights and responsibilities there are no differences. Immigration and rights of residence, social security benefits, defence are all decided on a UK wide basis. Likewise there are no borders between the different countries and of course they have the same currency, head of state etc.

There are however different constitutional mechanisms, designed mostly to compensate for the remoteness of Scotland and Wales from London. But the Assemblies, created by Devolution has very limited revenue raising powers and in Wales they are non-existent.

Moshe says that Scotland (not Wales!) has its own legal system. Only up to a point. The laws they implement are usually one and the same and Westminster law trumps Scottish law. More importantly the Scottish Court of Session (our Court of Appeal) is not the highest judicial body. That is the British, mainly English, Supreme Court (which used to be the House of Lords). The Privy Council Judicial Committee whilst not binding is ‘persuasive’.

The term British Citizen in the passport is therefore irrelevant (in fact it used to be Citizen of the UK and colonies, with the implication that you were a UK national).

Of course the definition of the Basques and other national minorities as belonging to the majority nation, for example Spanish or French, is a form of national oppression because it only recognises their individual rights and where there is a conflict, as with the Kurds in Turkey, then there isn’t even an equality of individual rights.

MM: This is exactly my point. The official French position that the French “nation” is co-extensive with French citizenry is a deliberate confusion, designed to legitimize oppression of national minorities.

TG: I’m not sure that the conflation of ‘nation’ and ‘citizenship’ by France, which Napoleon implemented in every country he conquered, was deliberately designed to legitimise national oppression. Rather it was important in the breakdown of feudal relations, the caste and city states. It was certainly welcomed by the Jews but those who were colonised, as in Algeria and Corsica, were of a different opinion.

TG: But in western Europe the conflation of citizenship and nationality is important, not least because it recognises that regardless of colour, race, ethnicity etc. one has the same rights as the next person.

MM: Yes; this is its positive side: recognition of equal individual rights. Its negative side is denial of collective rights of national minorities.

TG: In Israel it does matter, because citizenship accords only the right to reside, work and vote. It does not presume equality. Jewish Nationality in Israel means to be a member of a superior race of people, one with all the privileges, whereas citizenship is the most basic minimum. We can see that in Palestine Papers re the ‘peace talks’. One of Tsipi Livni’s primary demands was an exchange of land so that a future Palestinian statelet could include Israeli Arabs/Palestinians. In other words Israeli citizenship means that your presence if tolerated, not welcomed and certainly doesn’t imply equality.

MM: We agree on this. In Israel there is oppression of both kinds: there is no equality of individual rights of all citizens; and there is also denial of collective rights of the national minority.

TG: The French concept of citizenship and nationality being coterminous did indeed mean that Jews were not a national minority and/or an alien presence. To paraphrase Clermont Tenerre in the 1789 Constituent Assembly, ‘to the Jews as a nation nothing, to the Jews as individuals everything.’ This was welcomed by Jews everywhere, not just France (with the exception of the Orthodox and later the Zionists).

MM: Actually the Orthodox (especially in Western Europe) also had no objection – so long as the right of Jews to practise their religion was secure.

MM: No, Tony. It is not an Israeli deception. The Israeli passport uses the generally accepted terminology used in most other passports, inherited from French (that used to be the language of international diplomacy). It is this terminology that is misleading, but Israel is not responsible for it. In this terminology, “nationality” means citizenship – as its clear from its use in other passports. The Israeli passport simply follows this general international practice: it uses 2 languages, Hebrew and English. On the left-hand side under the rubric “nationality” it says: “Israeli”. On the right-hand side is the Hebrew translation. “Nationality” is translated as ezrahut, which is the Hebrew word for citizenship. There is no dishonesty in this translation, because the rubric “nationality” in a passport (Israeli, British, French or whatever) actually does mean citizenship and nothing else.

TG: Moshe I disagree. For most states nationality and citizenship are one and the same, they are not based on religion or ethnicity, so the answer to the heading ‘nationality’ is the same as it would be to ‘citizen’. But in Israel this is not the case. Citizenship accords very few rights. Nationality, i.e. Jewish nationality grants all sorts of rights and privileges and this is based on Israel being a state of the mythical ‘Jewish people’ rather than its own citizens. So it is clearly fraudulent to put ‘Israeli’ on a passport or any other document when the Supreme Court has consistently ruled there is no such thing.

Thus when Moshe says that the use of the term ‘Israeli’ under

nationality implies that there is such a thing as Israeli nationality

‘in the sense of citizenship’ I disagree. It does no such thing other

than to try and pull the wool over peoples’ eyes abroad as to the real

situation.

MM: Israel officially recognizes Israeli citizenship, which in its passports (as in passports of other states) comes under the heading “nationality”. Israel does not recognize an Israeli “le’om” or “leumiout”, which means nationality in the other sense (as in Kurdish or Basque nationality).

MM: Nonsense. I do not claim that there exists an Israeli nation. I actually deny it. Citizenship is a formally and officially defined status. Israeli citizenship clearly exists. To translate it as “Israeli nationality” is indeed a confusion. But Israel is not responsible of this particualr confusion. This is what most passports do.

TG: Moshe says that the Hebrew word “le’om” in the Israeli ID card does mean Jewish nationality, but of course it is a false nationality from which non-Jews are, of course, excluded. The very definition of nationality as being based on religion not residence or citizenship, is itself a reactionary throwback to medieval Europe. This is not a matter of semantics as very real human rights, such as the right to lease or buy ‘national’ land is dependent upon it. What is certain is that you cannot have Israeli nationality when you fly to Europe and then lose it in mid-air on the way back! Matter changes into energy when in motion but citizenship doesn’t change into nationality!MM: You are right. The Israeli official classification under “le’om” is nonsensical, discriminatory and confused. It is in any case a scandal that a person’s religion, ethnicity etc rather than citizenship is stated in their ID document.

TG: Of course the Israeli Supreme Court was right to deny there was such a thing as Israeli nationality because this would conflict with the basis of Israel as a Jewish state, not of its own citizens but Jews everywhere.

Correct.

TG: The question of Jewish Identity is not therefore just a racist question for Israel. It also affects Jewish people world-wide, not least in the United States, where most Jews would be considered non-Jews by Orthodox Jewry. It is clear that in the West today, in the absence of anti-Semitism and lacking any social or economic basis, the number of secular Jews is rapidly shrinking. Only Israel provides the racist glue to unite and define Jews.

Moshe and myself had a further discussion on this which is below, in which I refer to a debate on Jewdas.

Moshé Machover wrote:

Tony,Well

is Israel following the international convention, or is it taking

advantage of the confusion that results from the way the system works

internationally?Is there a difference?

And if there is, how can you tell? Who is supposed to be confused by an

Israeli passport? It is not a document that the general public looks at.

It is looked at by border officials and similar functionaries. They

know exactly what the rubrics mean. If they are “confused” by an Israeli

passport, it is only because it is back to front…Let

us stick to the facts. The normal international convention is that the

rubric “Nationality” in a passport refers to the bearer’s citizenship,

not to nationality in any other sense. The UK abides by this convention

and so do lots of other countries, including multi-national ones. So

does Israel. To make this even more obvious: in an Israeli passport the

rubric “Nationality” is correctly translated into Hebrew as “ezrahut”.

So if we have any reason to complain, it is not about the rubrics in an

Israeli passport.

This rubric is based, as you say, on nationality and citizenship being one and the same.No; “nationality” and “citizenship” are not in general one and the same. The former is ambiguous, depending on context.; the latter is not ambiguous.

However, in the context of a passport,

the convention is that the rubric “Nationality” is to be understood as

referring to citizenship. It does not follow that they are one and the

same in other contexts.But in Israel it isn’t the same.It is the same in the context of an Israeli passport

– as in the context of other passports. On the other hand, in other

contexts it is not the same in many countries, including Britain.Citizenship means very little if you are not a Jewish national and therein lies the deception.This

“deception” has nothing to do with passports. When an Israeli passport

of an Arab citizen states that s/he is Israeli by “Nationality” (ezrahut in Hebrew) it is not deceiving anyone. Who

is supposed to be deceived? Border officials know very well that what a

passport states under the rubric “Nationality” is the bearer’s

citizenship.However, when Israel claims that it does not discriminate against its Arab citizens, it is deceiving the world.ATB, Moshé

Hi Moshe

In October 1st 2013 an article by Laurie Goodstein appeared in the New York Times based on a survey by the Pew Research Institute. The article stated that:

The first major survey of American Jews in more than 10 years finds a significant rise in those who are not religious, marry outside the faith and are not raising their children Jewish — resulting in rapid assimilation that is sweeping through every branch of Judaism except the Orthodox.

The intermarriage rate, a bellwether statistic, has reached a high of 58 percent for all Jews, and 71 percent for non-Orthodox Jews — a huge change from before 1970 when only 17 percent of Jews married outside the faith. Two-thirds of Jews do not belong to a synagogue, one-fourth do not believe in God and one-third had a Christmas tree in their home last year.

“It’s a very grim portrait of the health of the American Jewish population in terms of their Jewish identification,” said Jack Wertheimer, a professor of American Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary, in New York.

The survey, by the Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project, found that despite the declines in religious identity and participation, American Jews say they are proud to be Jewish and have a “strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people.“

While 69 percent say they feel an emotional attachment to Israel, and 40 percent believe that the land that is now Israel was “given to the Jewish people by God,” only 17 percent think that the continued building of settlements in the West Bank is helpful to Israel’s security.

Jews make up 2.2 percent of the American population, a percentage that has held steady for the past two decades. The survey estimates there are 5.3 million Jewish adults as well as 1.3 million children being raised at least partly Jewish.

The survey uses a wide definition of who is a Jew, a much-debated topic. The researchers included the 22 percent of Jews who describe themselves as having “no religion,” but who identify as Jewish because they have a Jewish parent or were raised Jewish, and feel Jewish by culture or ethnicity.

However, the percentage of “Jews of no religion” has grown with each successive generation, peaking with the millennials (those born after 1980), of whom 32 percent say they have no religion.

“It’s very stark,” Alan Cooperman, deputy director of the Pew religion project, said in an interview. “Older Jews are Jews by religion. Younger Jews are Jews of no religion.”

The trend toward secularism is also happening in the American population in general, with increasing proportions of each generation claiming no religious affiliation.

But Jews without religion tend not to raise their children Jewish, so this secular trend has serious consequences for what Jewish leaders call “Jewish continuity.” Of the “Jews of no religion” who have children at home, two-thirds are not raising their children Jewish in any way. This is in contrast to the “Jews with religion,” of whom 93 percent said they are raising their children to have a Jewish identity.

Reform Judaism remains the largest American Jewish movement, at 35 percent. Conservative Jews are 18 percent, Orthodox 10 percent, and groups such as Reconstructionist and Jewish Renewal make up 6 percent combined. Thirty percent of Jews do not identify with any denomination.

In a surprising finding, 34 percent said you could still be Jewish if you believe that Jesus was the Messiah.

When Jews leave the movements they grew up in, they tend to shift in the direction of less tradition, with Orthodox Jews becoming Conservative or Reform, and Conservative Jews becoming Reform. Most Reform Jews who leave become nonreligious. (Two percent of Jews are converts, the survey found.)

Jews from the former Soviet Union and their offspring make up about 10 percent of the American Jewish population.

While earlier generations of Orthodox Jews defected in large numbers, those in the younger generation are being retained. Several scholars attributed this to the Orthodox marrying young, having large families and sending their children to Jewish schools.

Steven M. Cohen, a sociologist of American Jewry at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, in New York, and a paid consultant on the poll, said the report foretold “a sharply declining non-Orthodox population in the second half of the 21st century, and a rising fraction of Jews who are Orthodox.”

The survey also portends “growing polarisation” between religious and nonreligious Jews, said Laurence Kotler-Berkowitz, senior director of research and analysis at the Jewish Federations of North America.

The Jewish Federations has conducted major surveys of American Jews over many decades, but the last one in 2000 was mired in controversy over methodology. When the federations decided not to undertake another survey in 2010, Jane Eisner, editor in chief of The Jewish Daily Forward, urged the Pew researchers to jump in.

It was a multimillion-dollar effort to cull 3,475 respondents from a pool of 70,000. They were interviewed in English and Russian, on landlines and cellphones from Feb. 20 to June 13, 2013. The margin of error for the full sample is plus or minus three percentage points.

Ms. Eisner found the results “devastating” because, she said in an interview, “I thought there would be more American Jews who cared about religion.”

“This should serve as a wake-up call for all of us as Jews,” she said, “to think about what kind of community we’re going to be able to sustain if we have so much assimilation.”

The conclusion that can be drawn from such a poll is unmistakable. At the core of Jewish identity is belief in the Jewish religion, yet increasing numbers are atheists or of no religion. Although two-thirds identify with Israel, as assimilation reduces the number of Jews this attachment can only reduce numerically. Should we mourn what is the disappearance of Jewish people in the West? No, it’s only those who have a romantic attachment to the idea that the traditional forms of Jewish identity can be resurrected who will mourn such a loss. Indeed, in so far as the majority Jewish identity is based around support for Israel then the assimilation of the world’s largest Jewish community is to be welcomed.

That is partly why I was surprised, to say the least, that Ilan Pappe can be counted among the latter. In article Reclaiming Judaism from Zionism for Electronic Intifada of 18th October 2013 http://electronicintifada.net/content/reclaiming-judaism-zionism/12859#comment-16729

Ilan indulges in a shmaltzy nostalgia for a period which is not going to return. He notes, correctly that when it first appeared, most Jewish rabbis and the Orthodox rejected it as substituting worship of a state for a god. But times change. Jewish Orthodoxy has benefited from Zionism, not least in the vast subsidies it has received.

Ilan is also right that most secular liberal, socialist or communist Jews rejected Zionism, believing that anti-Semitism could fought where it was found. In that respect Zionism was unique in that it accepted anti-Semitism as the natural reaction to Jews in their midst. In his Diaries (p.6 Ed. Ralph Patai), Herzl wrote that ‘In Paris …I achieved a freer attitude towards anti-Semitism, which I now began to understand historically and to pardon. Above all I recognise the emptiness and futility of trying to ‘combat’ anti-Semitism.’ Likewise Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first President and the long-standing President of the Zionist Organisation wrote in his autobiography Trial & Error (pp. 90-91) of the leader of the anti-Semitic British Brothers League that ‘Sir William Evans Gordon had no particular anti-Jewish prejudice. He acted as he thought, according to his best lights and in the most kindly way, in the interests of his country.

We are even told that he was “horrified” by events in Russia, indeed more than that:

‘He was sorry but he was helpless. Also, he was sincerely ready to encourage any settlement of Jews almost anywhere in the British Empire, but he failed to see why the ghettos of London or Leeds or Whitechapel should be made into a branch of the ghettos of Warsaw and Pinsk.’

Normally meticulous as to his facts, Pappe’s sojourn into wishful thinking has also led to errors such as claiming that the description of the socialist Bund as Zionists who were afraid of sea-sickness was Trotsky’s comment. In fact it came from Plekhanov, a Menshevik who drifted so far to the right as to support Russian participation in World War I.

Pappe points to the contradiction inherent in secular, atheistic Zionists resting their claims to Palestine on a god whose existence they denied. But that is the whole point. By making such a claim they threw in their lot with reactionary Orthodox Judaism and turned their backs on socialism.

Pappe again goes astray when he asserts that the rejection of the Uganda plan was because of Christian opposition. In fact Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary who made such an offer, was himself a Christian Zionist. The primary opposition came from within the Zionist movement and in particular the Russian Zionists under Menachem Ussishkin.

Herzl in any event had originally preferred Argentina (Der Judenstaat). Pappe is right that the anti-Semitic Christian Zionists wanted to be rid of the Jews in Europe and have them return to Palestine in order to hasten the second coming of the Messiah – and if they refused to convert to Christianity they would perish in the flames of Armageddon.

It is true that Orthodox Jewry opposed end “Exile” in the Diaspora, holding that a ‘return’ of the Jews could not be hastened by the Zionist movement.

Pappe argues that it was ‘One of the greatest successes of the secular Zionist movement was creating a religious Zionist component that found rabbis willing to legitimise this act of tampering’. That may be true but it is simply evidence that religions change as circumstances change.

Pappe argues that ‘in the 1990s the two movements – the one that does not believe in God and the one that impatiently decides to do His work – have fused into a lethal mixture of religious fanaticism with extreme nationalism.’ I would suggest that such a mixture had long been formed when Ben-Gurion decided to form a coalition government in 1949, not with the ‘ left’ Zionist Mapam but the National Religious Party.

Pappe clings to the Ultra-Orthodox Jews such as Neturei Karta – who ‘even profess allegiance to the Palestine Liberation Organization, while the vast majority of the Ultra-Orthodox express their anti-Zionism without necessarily offering support for Palestinian rights.’ This is heavy with wishful thinking. Neturei Karta, the far-right of the Palestine solidarity movement, are an exception. Although ultra Orthodox Jewry formally states it is not Zionist, in practice they constitute the most rabidly racist section of Israeli society. When Rabbi Yitzhak Shapira wrote and had published ‘Torat HaMelech’ which was a guide to the killing of non-Jews, he was supported by hundreds of rabbis when the State of Israel was forced to take token action against him. See ‘Even Non-Jewish Children Must be Killed – Rabbi Yitzhak Shapira http://azvsas.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/even-non-jewish-children-must-be-killed.html Rabbi Schochet of the Racist Lubavitch – Big Questions Panellist and Guardian Columnist http://azvsas.blogspot.co.uk/2010/11/rabbi-schochet-of-racist-lubavitch-big.html and ‘Even Non-Jewish Children Must be Killed – Rabbi Yitzhak Shapira http://azvsas.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/even-non-jewish-children-must-be-killed.html

It is true that this ‘religious-nationalist mixture that now informs the Jewish society in Israel has also caused a large and significant number of young American Jews, and Jews elsewhere in the world, to distance themselves from Israel.’ but what form has this taken? As the article from the New York Times shows, it leads primarily to abandoning being Jewish altogether with a minority of secular Jews rejecting Zionism on the basis of its racism. But this can and will only be a minority as there is no alternative social or economic basis for the existence other than Zionism itself, which is inadequate. As Pappe rightly says ‘This trend has become so significant that it seems that Israeli policy today relies more on Christian Zionists than on loyal Jews.’

Where Pappe indulges in wishful thinking it is when says that ‘It is possible, and indeed necessary, to reaffirm the pluralist non-Zionist ways of professing one’s relationship with Judaism; in fact this is the only road open to us if we wish to seek an equitable and just solution in Palestine.’

The problem is that there is no way today, except for a tiny minority, for Jews to adopt an alternative, non-Zionist version of Judaism. Jewish Orthodoxy has long been captured for Zionism. Pappe writes that for Jews today it is; imperative to reconnect to the Jewish heritage before it was corrupted and distorted by Zionism.’ Again this is redolent of a heavy dose of wishful thinking. You can’t reverse the tide of history. It maybe an example of ‘nationalist criminality’ but it’s not something that can be reversed as there is no basis for example for the existence of the Bund. They and their supporters died in the Nazi genocide and only a remnant escaped, not least to Israel. A fascinating, yet very sad story of these remnants who lived primarily in Tel Aviv is Bundayim by Eran Torbiner, a supporter of Boycott from Within. These remnants made no concessions to Zionism but it was clear that they had had no impact or relevance on the settler colonial society surrounding them.

Ilan suggests that ‘We need to reclaim Judaism and extract it from the hands of the “Jewish State” as a first step towards building a joint place for those who lived and want to live there in the future.’ Not only is this impossible but I would ask why should one want to reclaim a dying religion? It certainly won’t affect the existence of Israel as a racist settler state, precisely because Israel’s racist is not based on but justified by an interpretation of the Pentateuch. Even if all Orthodox Jews became liberals overnight, Israel would still continue down the path to Armageddon. Ilan, like many others, needs to recognise that you cannot recreate the Jewish working class of Eastern Europe. Jews today have moved on and upwards socially and politically to the Right. No amount of self-delusions will change this simple fact.

Tony Greenstein