Review of Paul Bogdanor’s ‘Kasztner’s crimes – Tony Greenstein

Below is the unedited version of my review of Paul Bogdanor’s Kasztner’s Crimes which appears in the current issue of the Weekly Worker. I have included a section on the Haganah paratroopers, in particular Hannah Szenes, which was left out of the version published in Weekly Worker for reasons of space.

|

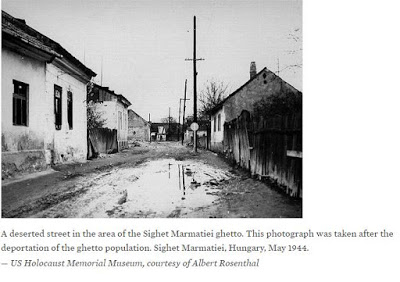

| Deportation of Jews from the town Koszeg, Hungary, 1944 |

|

| Paul Bogdanor – son of Vernon Bogdanor, Oxford’s dry constitutionalist – dedicated anti-Communist and Zionist – in damning Kasztner he sought to rehabilitate Zionism’s reputation during the Nazi era |

defended Rudolf Kasztner – the leader of Zionism in Hungary during the Nazi

occupation – against charges of collaboration with the Nazis. Yad Vashem, the

holocaust propaganda museum in Jerusalem, gave its stamp of approval to the

efforts to rehabilitate him. Tommy Lapid, chairman of its board of directors,

is on record as saying:

“There was no man in the history of the holocaust who

saved more Jews and was subjected to more injustice than Israel Kasztner.”1

At first sight it is somewhat strange

that Paul Bogdanor – who combines anti-communism and Zionism in equal measure –

has written a book which accepts the long-standing anti-Zionist criticism of Kasztner. That Kasztner was a Nazi collaborator who

deceived Hungary’s Jews into boarding the deportation trains to Auschwitz with

false information about being ‘resettled’ in a fictitious placed called

Kenyermeze. Why then this about-turn?

|

| Hungarian Jews waiting for the train to Auschwitz – they were misled by Kasztner and the Zionists into believing they were heading for the mythical Kenyermeze or Waldsee |

out to clear Kasztner. He was “tired of seeing Kasztner’s name come up

repeatedly in anti-Zionist propaganda”. Bogdanor now argues that “the

anti-Zionist claim that ‘Kasztner was part of a Zionist conspiracy with the

Nazis to exterminate the Jews of Europe’ is nonsense”. He was “not acting on

behalf of the Zionist movement: he betrayed it”.2

where Bogdanor is coming from. No anti-Zionist has ever alleged that there was

a Zionist conspiracy with the Nazis to exterminate Europe’s Jews – this kind of

falsehood is Bogdanor’s trademark. It is a straw man. The Zionist movement did,

however, collaborate with the Nazis.

columnist for David Horowitz’s Frontpage Mag,3 he denied

this, despite being listed as a columnist.4 He also contributed an

article, ‘Chomsky’s war against Israel’,to The Anti-Chomsky reader,5

edited by Horowitz. Frontpage Mag had previously published Bogdanor’s article, ‘The top 100 Chomsky lies’. Bogdanor has an

obsession with Jewish anti-Zionists – myself included.6

writes should be treated with the utmost caution is his political and

intellectual dishonesty. Bogdanor would defend the slaughter of the innocents

if he thought that King Herod was a Zionist.

|

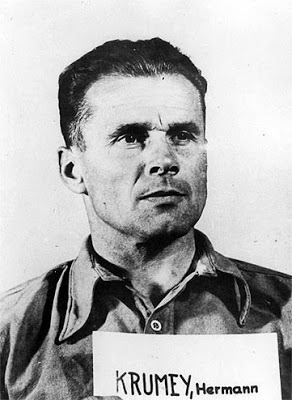

| Adolf Eichmann – Bogdanor maintained that everything he said couldn’t be trusted but nonetheless ended up quoting from his 1956 interviews |

his criticism of Lenni Brenner, whom Ken Livingstone relied on when he said

that Hitler supported Zionism. Bogdanor criticised Brenner’s use of an

interview with Adolf Eichmann by Wilhelm Sassen, a Dutch Nazi journalist.7

Bogdanor described this interview as a “transparently worthless source”.8

Of course, just because a quotation is from a Nazi war criminal does not make

it invalid, especially given that the interviews were conducted freely, long

before his kidnapping.9 Otherwise one must eschew all Nazi sources:

eg, The Goebbels diaries.

“Nazi mass murderers – and Eichmann above all – were pathological liars”.10

In reply I asked whether it is a principle that one never quotes or cites what

Nazi murderers say? Perhaps one should not quote Nazi documents too? Sometimes even

liars tell the truth. Or maybe Bogdanor is an exception to the rule?11

His response was: “Just as citing a Nazi sympathiser comes naturally to one who

treats Adolf Eichmann as a truth-teller, so reliance on Stalinists is only to

be expected from a writer for the Communist Party of Great Britain.”12

Imagine my surprise when Bogdanor’s book came out and there was a reference in

the footnotes to Eichmann’s interview for Life magazine!13

the Sassen interview with Eichmann was used extensively by the Israeli

prosecution in the Eichmann trial. Eichmann’s Defence of his actions in organising the deportations to the death camps was that he was just

following orders. The Prosecution quoted this from his interview: “I thought my

orders through and participated in their implementation because I was an

idealist.”14 Eichmann was then cross-examined using the “efficient

weapon of the memoir that Eichmann dictated to Sassen”.15 Presumably

the Prosecutor in the Eichmann trial was unaware that he was quoting from a

“transparently worthless source”.

Israel in 1961, was, according to Israeli historian and journalist Tom Segev,

meant to “expunge the historical guilt that had been attached to the Mapai

[Israeli Labour Party] leadership since the Kasztner trial”.16

in the dock

|

| Rudolf Kasztner – head of Hungarian Zionist movement – on the Knesset list of Mapai (Israeli Labour Party) was also a Nazi collaborator |

Ever since Kasztner had come to live

in Palestine in early 1947, rumours had followed him. An inquiry in 1946 by the

Jewish Agency, at the Zionist Congress in Basel, dismissed complaints brought

by Moshe Krausz, who headed the Palestine Office in Budapest, for “lack of

evidence”.17

“felt compelled to issue a statement praising Kasztner’s ‘tremendous work

during the war’” (p.264). It is difficult to see why Mapai felt under any such

compulsion unless they felt that a failure to defend Kasztner would also

rebound on their own record during the holocaust. Nor does Bogdanor explain why

“the Jewish Agency had unceremoniously fired Krausz from his post” (p.270).

brought a libel action, at the insistence of the state, against Malchiel

Gruenwald, a Hungarian Jew who had published a newsletter alleging that

Kasztner was guilty of collaboration with the Nazis.

The first comprehensive account of

what became known as the Kasztner trial was Perfidy by the Hollywood

producer and screenwriter, Ben Hecht. Hecht was a supporter of the dissident

Zionists, Peter Bergson and Shmuel Merlin of the Emergency Committee to Save

the Jews of Europe. Bergson and Merlin had incurred the wrath of the US Zionist

leadership under Stephen Wise and Nahum Goldman because they insisted on

rescuing Jews, whatever the destination, whereas it was a cardinal principle

for the Zionist movement that rescue should be centred on Palestine only.

demonised. My copy includes a ‘review’ article, ‘Ben Hecht’s Kampf’, by

Shlomo Katz published in Midstream magazine. Hecht was subject to the

same personal attacks and denigration as Hannah Arendt, whose Eichmann in

Jerusalem – a book based on her reports of the Eichmann trial for the New

Yorker – had touched on exactly those subjects that the trial had been

designed to avoid.18 Arendt described how

… the campaign

(was) conducted with all the well-known means of image-making and

opinion-manipulation … [it was] as though the pieces written against the book

(and more frequently against its author) “came out of a mimeographing machine”

(Mary McCarthy) … the clamour centred on the ‘image’ of a book which was

never written, and touched upon subjects that often had not only not been

mentioned by me, but had never occurred to me before.

Kasztner, despite repeated attempts to exonerate him: for example, Gaylen

Ross’s film Killing Kasztner: the Jew who dealt with the Nazis19

or Motti Lerner’s Kasztner,as well as Yechiam Weitz’s The man who

was murdered twice and Anna Porter’s semi-fictional Kasztner’s train.

Vashem, Israel’s official “World Holocaust Memorial Center”, led by Yehuda

Bauer, have for years tried to exonerate Kasztner. Bauer wrote that it seems to me

there are not many people who [like Kasztner] saved many Jews in the holocaust.

There are certainly not many who saved for sure 1,684 Jews and contributed to

the rescue of tens or hundreds of thousands.20

presided over by Benjamin Halevi of the Jerusalem District Court: On June 21

Halevi found that

“when Kasztner received this present [a train out of Hungary

for Kasztner’s friends and the Zionist/Jewish elite] from the Nazis, he had

sold his soul to the German Satan.”21

Halevi went on:

Eichmann did not

want a second Warsaw. For this reason, the Nazis exerted themselves to mislead

and bribe the Jewish leaders …

The Nazi patronage

of Kasztner, and their agreement to let him save 600 prominent Jews, were part

of the plan to exterminate the Jews … The opportunity of rescuing prominent

people appealed to him greatly. He considered the rescue of the most important

Jews as a great personal success and a success for Zionism.22

On May 2 1944, 13 days before the

trains started for Auschwitz, Kasztner had reached an agreement with Hermann

Krumey, Eichmann’s deputy in Hungary:

Kasztner possessed

at that moment the first news about the preparation of the gas chambers in

Auschwitz for Hungary’s Jews … [he could] warn the leaders and the masses about

the real danger of the imminent total deportation facing Hungary’s Jews, and

immunise them against Nazi deceptions … The other way opened for Kasztner by

Krumey was the method of rescuing Jews by the Nazis themselves, with their

help, according to agreement with the heads of the SS 23

Deceit

On April 24 Rudolf

Vrba and Alfred Rosenberg, two Jewish escapees from Auschwitz, reached

Slovakia. They described to the Jewish Council Auschwitz’s purpose (which

previously had been thought of only as a labour camp) and provided details of

the gas chambers and crematoria, as well as an estimate of the numbers of those

killed. On or around April 29 Kasztner was given a copy of their report – known

as The Auschwitz Protocols – and one was sent to his counterpart in

Switzerland, Nathan Schwalb. Both Kasztner and Schwalb took a decision to

suppress them. Halevi found that:

…

Kasztner understood very well … that the Prominents as a whole and his friends

in Kluj in particular would not be rescued from the holocaust if the mass heard

a hint about the real purpose of the operation: to save the leaders from the

holocaust prepared for the people.

The

association with the heads of the SS, on which Kasztner placed the entire fate

of the rescue, forced him to withhold his information about the extermination

plans from the majority of Hungary’s Jews (p145).24

Once Kasztner had agreed to be a

partner of Eichmann, there was no way out: “Kasztner didn’t want to destroy by

his left hand what he built with his right …”25

the Jewish Agency Rescue Committee (Vaada),26 to warn other Jewish

communities, despite having access to a telephone and permits with which to

travel.27 The evidence given by survivors of the Hungarian holocaust

was that Kasztner and his friends went out of their way to deceive the Jews as

to the destination of the trains. They were told they were going to be

resettled in Kenyermeze.

1948 celebration for Kasztner in Tel Aviv, given by those on the train, and how

he confronted Kasztner:

Kasztner, “You were a Quisling! You were a murderer! … I know that you,

Kasztner, are to blame for the Jews of Hungary going to Auschwitz. You knew

what the Germans were doing to them. And you kept your mouth shut.” Kasztner

didn’t answer me. I asked him, “Why did you distribute postcards from Jews

supposed to be in Kenyermeze?” 28

was deported with his family to Auschwitz. Their non-Jewish servant infiltrated

the ghetto and begged them to come with her to a shelter she had prepared: “…

we would surely have accepted her offer, had we known that ‘destination

unknown’ meant Birkenau” (pp.109-10). Kasztner did not merely suppress the

Auschwitz Protocols. He, Vaada and the Jewish Council actively deceived Jews as

to their destination. Both the Jewish leaders and the Zionists collaborated in

the destruction of the Hungarian Jewish community.

trial. The Mapai (Labour Zionist) government submitted an immediate appeal to

the supreme court against Halevi’s verdict. Kasztner’s representative, attorney

general Chaim Cohen, outlined the basis for the appeal:

If in Kasztner’s

opinion, rightly or wrongly, he believed that one million Jews were hopelessly

doomed, he was allowed not to inform them of their fate; and to concentrate on

the saving of the few … He was entitled to make a deal with the Nazis for the

saving of a few hundreds and entitled not to warn the millions. In fact, if

that’s how he saw it, rightly or wrongly, that was his duty.

… But what does

all this have to do with collaboration? … It has always been our Zionist

tradition to select the few out of the many in arranging the immigration to

Palestine. Are we therefore to be called traitors?29

cleared Kasztner by a majority of four to one. Shimon Agranat gave the leading

opinion for the majority. Kasztner “had the right to keep silent”, said

Agranat, and his decision to include a high number of Zionists on the train was

“perfectly rational”.30

|

| Col. Kurt Becher of the Waffen SS – Kasztner testified on his behalf at Nuremburg on behalf of the Jewish Agency |

The supreme court did not challenge

the facts found by the lower court. Rather it disagreed with the verdict on

political grounds. All five judges upheld Halevi’s verdict on the “criminal and

perjurious way” in which Kasztner after the war had saved Nazi war criminal

Kurt Becher,31 the personal representative of Himmler in Hungary.

Kasztner was extremely proud that he

had rescued the “prominent Jews”.32 There was no doubt that he was

aware of the fate of those who were being deported. He boasted that he was the

best informed about the perilous situation of the Jews at that time: “We had,

as early as 1942, a complete picture of what had happened in the east to the

Jews deported to Auschwitz and the other extermination camps.”33

Chaim Cohen said:

The man Kasztner

does not stand here as a private individual. He was a recognised

representative, official or non-official, of the Jewish National Institutes in

Palestine and of the Zionist Executive; and I come here in this court to defend

the representative of our national institutions.34

Kasztner was a lone individual, he was defended so avidly by the Zionist institutions,

including its supreme court.

motives

When Bogdanor says that his original

intention was to write a book exonerating Kasztner we can believe him. The

evidence is so damning against Kasztner that the first question to ask is why,

for over 60 years, has the Zionist movement defended a war criminal who,

Bogdanor admits, was a Nazi agent?

|

| SS General Hans Juttner – former head of the SA – Kasztner testified in his favour on behalf of the Jewish Agency |

not merely given evidence on behalf of Kurt Becher of the Waffen SS, but also

on behalf of SS general Hans Juttner and Herman Krumey – Eichmann’s deputy in

Hungary, who organised the mechanics of the deportations. Kasztner even tried

to save Dieter Wisliceny, the butcher of Slovakian and Salonikan Jewry, from

the gallows in Czechoslovakia in 1948.

Bogdanor pretends that Kasztner gave

this testimony as a private individual. In fact he represented both the Jewish

Agency and the World Jewish Congress. Shoshana Barri concludes in her

painstaking dissertation: “It is clear, however, that the Agency did know of

the testimony’s existence, since Kasztner’s intervention on behalf of Becher at

Nuremburg is mentioned in his July 1948 letter to Kaplan.”35

Kasztner emphasised in his Nuremburg statement of August 4 1947 that “he was

testifying not only on his own behalf, but on behalf of the Jewish Agency and

the World Jewish Congress”.36

in Ha’aretz of December 2 1994 (conducted by Gideon Raphael, who helped

found Israel’s foreign ministry), that both he and Eliahu Dobkin of the Jewish

Agency had strongly objected to Kasztner testifying on behalf of the Jewish

Agency. Dobkin, who was a signatory to Israel’s Declaration of Independence,

denied at the trial that he had even heard of Becher. Raphael in the same

interview accepted that Dobkin’s testimony at the Kasztner trial – i.e., that he

had never heard of Becher – was a lie. Barri refers to archival material of the

Jewish Agency, which suggests that they both knew of Kasztner’s testimony on behalf

of Becher.

his testimony between September 1945 – when he gave an affidavit condemning

Becher, Krumey and company as cold-blooded killers – and January 1946, when he

called them rescuers. What Bogdanor fails to mention is why did Kasztner again change his mind when he wrote a 300-page

report for the Jewish Agency in the summer of 1946, before giving his testimony

at Nuremburg in 1947?

Bogdanor suggests that Kasztner was coming under pressure

from holocaust survivors arriving in Israel, who alleged that he was a

collaborator. According to Bogdanor, the way to clear his name was to show that

these Nazi war criminals had actually been going around with Kasztner saving

Jews from extermination. In other words the best way for Kasztner to prove he

was not a collaborator was by testifying in favour of Nazi war criminals!

demonstrates is that Bogdanor will go to any lengths in order not to

reach the most obvious answers. The reason that the Zionist leadership in

Israel had no objection to Kasztner’s testimony was because they knew that they

too were equally guilty (pp.254-59). After the war the Israeli state employed

Nazi war criminals like Walter Rauff, the inventor of the gas truck, which was used both in the so-called Euthenasia campaign between 1939 and 1941 and then at the end of 1941 was used in the first extermination camp, Chelmno. Clearly

there was no principled objection to Kasztner’s testifying on behalf of Nazi

war criminals.37

book is that it contains very little that was not already known. The primary

evidence against Kasztner came from the survivors of the Hungarian holocaust,

who testified that they had been deliberately fed misinformation to persuade

them that they should board the trains. Bogdanor tries to exonerate the Zionist

movement by pretending that, but for Kasztner, the Zionist resistance and

Hehalutz youth movement would have led an uprising and that the deportations

would have been foiled. Randolf Braham, the historian of the Hungarian

holocaust, quotes Gyula Kádár, the former head of the Hungarian military

intelligence service, as saying that “If [Hungary] had had as many ‘resistance

fighters’ before March 19 1944 as it had in May 1945 and later, Hitler would

not have risked the occupation of the country.”38 According to Edmund

Veesenmayer, Hitler’s plenipotentiary in Hungary, “a day in Yugoslavia was more

dangerous than a year in Hungary”.39

‘Like the claims

of many other rescuers, the post-war accounts by their leaders are also

sometimes self-serving and shrouded in myths…. One cannot possibly determine

the exact number of Jews who were actually rescued by the Halutzim. Their

rescue and relief operations, however relatively modest, were real. The myths

lie in the leaders’ basically self-aggrandizing post-war accounts that

exaggerate both the scope and accomplishments of these operations.’

Braham specifically mentions Yehudah Bauer’s reliance on ‘self-serving testimonies’ that Joszef

Meir, of the left-Zionist Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, was involved “in sabotage and the

derailing of trains” commenting caustically that ‘No corroboration for this

claim has been found to date.’ 40

Approximately 1,500 Hungarian Jews

escaped across the Hungarian-Romanian border, the majority of whom “managed to

save themselves without the aid of any rescue groups”.41 Braham

quotes Gyula Kádár: “Had Hungary had as many mass rescuers during the German

occupation period as were identified or self-proclaimed after the war, most of

the Jews of Hungary would have survived the holocaust.” Braham concludes that

“there is a potential danger that the myths of rescue, if left unchallenged,

may acquire a life of their own, threatening the integrity of the historical

record of the holocaust.”

of the Kasztner affair is that he has no integrity. His only concern is to

exculpate a Zionist movement that even the most assiduous and devoted of

Zionist historians – such as Shabtai Teveth, Ben Gurion’s official biographer, raises serious questions about. Teveth titled the chapter on the holocaust in

his biography of Ben Gurion ‘Disaster means strength’, writing that “the war

and the holocaust were not in his power to control, but he again resolved to

extract the greatest possible benefit from the catastrophe”. Teveth concluded:

“If there was a line in Ben Gurion’s mind between the beneficial disaster and

an all-destroying catastrophe, it must have been a very fine one.”42

Such subtleties entirely pass Bogdanor by.

time on the affair of the three Haganah agents, Hannah Senesh, Yoel Palgi and

Peretz Goldstein who parachuted into Yugoslavia and joined Tito’s partisan

fighters in March 1944. In June they

crossed into Hungary. Szenes was almost

immediately arrested. When the other

two parachutists arrived in Budapest Kasztner informed the Gestapo of their

arrival and ‘persuaded’ Palgi to hand himself in and forced Goldstein into

surrendering. Despite repeated requests

from her mother, Kasztner refused to provide any help to Hannah. This was brought out clearly when both

Kasztner and Hannah’s mother, Katrina, were cross-examined in the Kasztner

trial.[43]

to discern. The parachutists were

Haganah and British agents. Given

Kasztner’s relationship with the Nazis, the arrival of these agents threatened his

cosy relationship with the Nazis. He

therefore abandoned them. All three were tortured by the Hungarian secret

police and Szenes was executed on November 7th.

Goldstein was sent to Oranienberg concentration camp where he died.

Palgi was the only one who survived, having escaped from a train to

Germany. He later testified in the

Kasztner trial.

already known. Bogdanor alleges that the

purpose of the parachutists’ mission was to ‘organize resistance and rescue

attempts.’ [44] This is highly unlikely not least because 32

agents were unlikely to have any effect on the capabilities of the already

extant resistance in for example Yugoslavia.

Their true purpose was ‘to reconstruct the crumbling Zionist youth

movements there [Europe] after the war’ [45]

the parachutists ‘outwardly defined theirs as a rescue mission… their primary

goal was in effect to influence the survivors to choose Palestine as their

ultimate destination.’ In short to

rebuild the Zionist infrastructure in Europe.[46] As the war was coming to an end, the Zionist

leaders became concerned that the survivors of the Holocaust might not choose

to go to Palestine.[47] As Arthur Sulzberger, the publisher of the New York Times, declaimed:

The unfortunate

Jews of Europe’s D.P. Camps are helpless hostages for whom [Israeli] statehood

has been made the only ransom… why in God’s name should the fate of all these

unhappy people be subordinated to the single cry of statehood.’ [48]

1943, allegedly gave assistance to refugees from Poland, Vienna and other

Nazi-occupied countries. One suspects that it mainly confined its assistance to

Zionists. In his first chapter, ‘The underground’, Bogdanor leads us to believe

that there was a veritable rescue organisation that saved up to 25,000 Jews. In

fact most Jews who escaped to Hungary from Slovakia and other countries did so

without any help from Vaada.

how Vaada operated, when he described how he fled as a boy of 17 across the

border from Slovakia to Hungary. In Budapest he went to the headquarters of the

Zionist organisation. After having told his story, a stern-faced man

in his middle-30s responded:

“You are in Budapest illegally. Is that what you

are trying to say?”

“Yes.” “Don’t you know you are breaking the law?”

I nodded,

wondering how a man with such a thick skull could hold down what seemed like a

responsible position.

“And you expect to get work here without documents?”

“With false documents.”

At this point Vrba remarks that, if

he had torn up the Talmud and jumped on it, I do not think I

could have shocked him more … he roared:

“Don’t you realise that it’s my duty

to hand you over to the police?”

Now it was my turn to gape. A Zionist handing

a Jew over to fascist police? I thought I must be going mad.

“Get out of here!

Get out as fast as a bad wind!”

years before I realised just what [the National Hungarian Jewish Relief Action]

and the men inside it represented.

to Slovakia. Caught at the border, he ended up in Majdanek concentration camp

and then Auschwitz.49

Time and again in his book Bogdanor

betrays his primary motivation – to exonerate the Zionist movement at

Kasztner’s expense. When he mentions the leaders of the Central Jewish Council

he describes these bourgeois worthies – led by Samu Stern, a friend of Hungarian

regent Miklós Horthy – as “anti-Zionist personalities”. They were nothing of the

kind. Their distinguishing feature was that they were bourgeois

politically. As even Bogdanor mentions, Abwehr (Nazi intelligence) agents

“offered Kasztner’s committee control over the official Judenrat” (p19).

accepting that “in the few days that followed the German invasion we became

the leaders of Hungarian Jewry. Even Samu Stern deferred to their

decisions” (p.24). Bogdanor cites the testimony of Kasztner at the trial: “The

Judenrat body handling the provincial towns was a Zionist body” (p.101). Vaada

had immunity passes and were able to use their own cars, had telephones and did

not have to wear the yellow star.

of Zionism

What then can be said in favour of

Bogdanor’s book? There can be little doubt now as to the role of Kasztner in

betraying and deceiving the Jews of Hungary – not least in his home town of

Cluj (Kolosvar), which was only two-three miles from the Romanian border. In

falsely claiming that it was impossible to cross because the Nazis had

increased their patrols, Kasztner actively helped send the Jews of that region

to their death. It is a fact that most of those who attempted to cross that

border actually succeeded.

testimony of the Hungarian holocaust survivors in the Kasztner trial and how

they were tricked into getting onto the trains is revealing (pp.89-94), although

most of this too is in Perfidy. But his suggestion that Kasztner acted

as a lone wolf is unsustainable. He was one of a number of members of Vaada and

all but one survived the Holocaust (pp. 52-56). The suggestion that “the Jewish

Agency was being deceived by Kasztner” has no foundation. By his own account,

the Jewish Agency ‘Rescue Committee’ had been transformed into “a client body

of the most dangerous Nazis” in the SS (p.59). Even Bogdanor is forced to admit,

regarding Palestine, that there was a “disastrous aversion of the Labour

Zionists to publicity in matters of rescue” (note 16, p.85).

However,

he never asks why this was the case.

Repeatedly the Jewish Agency

executive in Jerusalem refused to take the Nazi threat to Hungarian Jewry

seriously. Vanya Pomerantz, a member of the agency’s Istanbul mission, informed

them on May 25 1944 that 12,000 Jews a day would be deported, beginning the

following week (in fact the deportations had already begun). On June 11 Gruenbaum was alone in informing his Jewish Agency

colleagues that 12,000 people a day were being transported to their deaths. Yitzhak Gruenbaum was alone in describing the Nazi ‘offer’ as a “satanic provocation”. On June 18 he noted that the deportations were continuing incessantly. But the public and the world were told nothing.50

Bogdanor

says that at their meeting of June 11 (and also May 25) Gruenbaum’s colleagues,

including Ben Gurion, were “confused” because of Nazi deception.(pp.130-131)

already been murdered by the Nazis, it was obvious that the Jews of Hungary

were in mortal danger. It was not ‘confusion’, but indifference, that led the

Jewish Agency executive initially to reject even a call on the Allies to bomb

Auschwitz or the railway lines leading to the camp. They had a more important

priority: building their racist state. The fact that it was the Swiss, not the

Palestinian, press that broke the news of the deportations, which led to Horthy

putting an end to them, speaks volumes. The Jewish Agency was content with

private, routine pleas to the Allies. It undertook no propaganda campaign to

put pressure on the Horthy regime.

and the Swiss press, at the end of June, in tandem with Pope Pius XII, King

Gustav of Sweden and the American bombing of Budapest on July 2 1944, to halt

the deportations to Auschwitz. Despite the Zionist axiom that Jews can only

rely on other Jews, it is a fact that it was non-Jews, not the Zionists, who

saved a quarter of a million Hungarian Jews. It was the Swedish count, Folke

Bernadotte, who was responsible for negotiating with Himmler for the rescue of

over 30,000 concentration camps inmates; and Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg

who was responsible for rescuing thousands of Jews in Budapest. Bernadotte’s

reward was to be murdered by pro-Nazi Zionist terrorists of the Stern Gang,

with the knowledge and support of the Labour Zionist Haganah, in Jerusalem in

September 1948. Wallenberg died at the hands of the Stalinist

criminals in Russia.

been “recruited as a collaborator by the Nazis” (p.71), but this is, of course,

exactly what anti-Zionists have maintained for years! And his conclusion – that

Kasztner claimed false credit regarding the Jews sent to Strasshoff in Vienna

(some 12,000-16,000 of whom survived, because the Nazis needed labour to dig

anti-tank ditches) – is also well known. I agree with his conclusion regarding

the Nazi offer of one million Jews in exchange for 10,000 trucks to be used

against the Russians in the east – the so-called ‘Blood for Trucks’ deal.51 It was clearly meant to distract from the deportations.

Bogdanor’s book is that the Zionist movement did indeed collaborate with the

Nazis during the war and obstructed the rescue attempts of others. This

continues to haunt the Zionist movement today, Bogdanor notwithstanding.

www.haaretz.com/yad-vashem-hopes-kastner-archive-will-end-vilification-1.226041.

www.timesofisrael.com/on-quest-to-clear-kasztner-historian-shocked-to-prove-nazi-collaboration.

Livingstone got it right over Nazi support for Zionism’, June 17 2016:

http://azvsas.blogspot.co.uk/2016/06/why-ken-livingstone-got-it-right-over.html.

http://archive.frontpagemag.com/bioAuthor.aspx?AUTHID=3012.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Anti-Chomsky_Reader.

and the Nazi apologists’:

www.paulbogdanor.com/antisemitism/greenstein/nazi.html.

Nizkor site, which is dedicated to rebutting holocaust denial:

www.nizkor.org/hweb/orgs/german/einsatzgruppen/esg/trials/profiles/confession.html.

http://fathomjournal.org/an-antisemitic-hoax-lenni-brenner-on-zionist-collaboration-with-the-nazis.

http://azvsas.blogspot.co.uk/2016/06/why-ken-livingstone-got-it-right-over.html.

Greenstein’s house of cards’:

www.paulbogdanor.com/antisemitism/greenstein/tonygreenstein.pdf.

and the Zionist three-card trick – why Ken Livingstone was right’ (part 2):

http://azvsas.blogspot.co.uk/2016/07/paul-bogdanor-and-zionist-three-card.html.

Greenstein’s sleight of hand‘: www.paulbogdanor.com/antisemitism/greenstein/tonygreensteinreply.pdf.

note 1.

issues: www.newyorker.com/magazine/1963/02/16/eichmann-in-jerusalem-i.

http://forward.com/culture/116718/kasztner-hero-or-devil.

Kasztner vs Hannah Szenes: who was really the hero during the holocaust?’:

www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-1.557024.

Orr’s contribution to Jim Allen’s book, Perdition: a play in two acts (London 1987), pp88-89.

sent to Schwalb almost immediately. See F Baron, ‘The “myth” and reality of

rescue from the holocaust: the Karski-Koestler and Vrba-Wetzler reports’ The Yearbook of the Research Centre

for German and Austrian Exile Studies No2 (2000), pp171-208.

that Kasztner’s job was co-funded by the US-based Joint Distribution Committee,

a non-Zionist Jewish charity, along with the Jewish Agency. The latter had

sought to set up a Relief and Rescue Committee in Budapest, only to find that

one had already been established (A Porter Kasztner’s train London 2009, p61). Akiva Orr describes Kasztner’s

Relief Committee as “affiliated” to the Jewish Agency Relief Committee in

Palestine (in J Allen Perdition:

a play in two acts London

1987, p81). Krausz was a member of the religious Zionist Mizrahi, whereas the

Jewish Agency was controlled by Mapai. Randolf Braham says: “The Rescue

Committee of Budapest was established early in 1942, under the auspices of the

Rescue Department of the Jewish Agency for Palestine” (Patterns of Jewish leadership in Nazi

Europe 1933-1945

p281, Jerusalem 1979).

in Hungary

Hilberg 1981, p134.

in Hungary

Hilberg 1981, p881.

Jewish Agency treasurer, as well as being Israel’s first finance minister and

deputy prime minister.

(Ishoni), ‘The question of Kasztner’s testimonies on behalf of Nazi war

criminals’ Journal

of Israeli History

18: 2, 144 (1997).

www.haaretz.com/weekend/magazine/in-the-service-of-the-jewish-state-1.216923.

‘Rescue operations in Hungary: myths and realities’ East European Quarterly Vol 38, summer 2004, p173.

that up to 5,000 escaped – Y Bauer Jews for sale? Yale 1996, p160.

of a Jewish Paratrooper Behind

University Press. Judith Baumel, Ha’aretz 13.6.03.

1983, p. 260, Croom Helm, London, described the purpose of the Haganah

parachutists as to ‘organise Jewish resistance and rescue’.

Eastern Studies, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Apr., 1994), p. 359.

created modern Israel, 2016.

cannot forgive London 1964, pp.27-28.