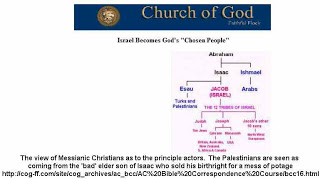

In an article, ‘The End of the Secular Majority’ Israel’s only liberal daily, Ha’aretz laments the advance of the ultra-orthodox and the decline of the secular majority. What the early Zionist pioneers chose to ignore was that by basing their claims to Palestine on the holy scriptures, they had handed the power of defining who was chosen and privileged to the religious. It was logical therefore, in order to prevent any breach between the Israeli state and the religious, that personal matters – divorce, marriage, birth – were handed to the Israeli rabbinate, even though the definition of a Jew for the purposes of the Law of Return was based on the Nazi Nuremburg Laws.

It is interesting that despite the continual whines and protests about ‘anti-Semitism’ 67% – two-thirds of Israelis consider themselves the chosen people. Chosen to serve was the original religious notion but that, along with much else, has gone by the board. Choseness now has been transformed into an ideological plank of current Israeli perception. There is no serving but rather having others serve them – the thousands of imported labourers from Asia (no problematic political claims of a right to return). The Chosen People idea has been transformed through Israeli settler-colonialism into a belief in a Jewish Herrenvolk, the master race with Palestinians destined, at best, to play the role of hewers of wood and drawers of water.

Hat tip to jewsansfrontieres for spotting this.

Tony Greenstein

A new survey reveals that 80 percent of Israeli Jews believe in God and 65 percent in life after death. Does the religious revival mean there’s no hope for a democratic Jewish state?

By Assaf Inbari

Once there was a secular majority. No more. That’s the finding of a comprehensive, newly published study, “Beliefs, Observances, and Values among Israeli Jews,” conducted by the Guttman Center for Surveys, which operates under the auspices of the Israel Democracy Institute.

According to the survey, 80 percent of Israeli Jews believe in God; 67 percent believe that the Jews are the chosen people; 65 percent believe that the Torah and precepts are God-given; and 56 percent believe in life after death. It’s no longer a matter of popular fondness for traditional customs. This is definitely a matter of belief: three of every four Israeli Jews are not atheists. Even if they are not Sabbath observers, they cling to the basic belief system of the Jewish religion.

The illusion of a “secular majority” has been with us for many years, sabotaging the prospect of forging a pluralistic Jewish melting pot in Israel. The reason this did not happen is that atheists who believe they constitute a majority are as domineering as Haredim. It will happen only if we understand that it’s not atheism – which is shared by ever-declining numbers of Israeli Jews – but pluralism, which is still shared by the majority, that is the basis for a democratic Jewish state.

The imaginary melting pot, into which Israel tried in vain to stuff the ultra-Orthodox and national-religious population groups, never had a chance. The smashing of the melting pot had the effect of reinforcing the insularity of the different communities. With separate education systems, separate cultural constellations, niche parties, separate residential areas and the selective application of the country’s laws, each group did what it thought best for itself. Underlying the dandyish academic talk about “multiculturalism” is a frightening reality of ongoing intercommunal enmity that threatens to boil over into fratricidal war. Israeli statehood, built without foundations, is crumbling into a politics of crude, unrestrained, underhanded opportunism that is increasingly racist and less and less democratic.

This is what happens when the “secular majority” exempts itself from Judaism and leaves it in the hands of the Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox – as though Judaism were a given, frozen entity whose essence is known to the Orthodox and the Haredim. But Judaism was never a frozen entity. If it had been, the siddur – the prayer book – would not have replaced animal sacrifices; the oral Law would not have provided the written Torah with a revolutionary exegesis; festivals and commemorative dates like Hanukkah and Tisha B’Av would not have been set; and we would have continued to stone wayward sons.

The history of Judaism is the history of its transformation, not to mention the multitude of streams that have existed in every historical period (Israel and Judah, Sadducees and Pharisees, kabbalists and philosophers, Hasidim and Mitnagdim, religious Zionists and anti-Zionist Haredim ). In the face of Haredi rabbis for whom Judaism means the exclusion of women and evading civil obligations, the secular stream should have come forward as a Jewish group fearful for the image of Judaism and its enlightened, egalitarian and democratic realization. As a Jewish stream engaged in a struggle for the image of Judaism, the secular stream should have confronted all the national-religious rabbis for whom Judaism means ignoring the existence of the Palestinians, perpetuating the discrimination against Israel’s Arab population and viewing themselves as the true commanders of the Israel Defense Forces. This will not happen as long as the secular stream continues to think it is the majority, and as long as it thinks that as “the majority” it can allow itself to ignore Judaism in its constellation of considerations.

Common ground

Demographically, there are no two ways about it. Since the natural increase rate of the Orthodox and the ultra-Orthodox is 10 times that of the secular population, the future is already here. We need to deploy for it. We are living in the final moments when processes may still be set in motion to shape Israeli society as a pluralistic Jewish community, because people of moderate outlook still constitute a solid majority here. Just as only three percent of those asked in the Guttman Center survey describe themselves as “secular, antireligious” (as against 43 percent who describe themselves as “secular, not anti-religious” ), the majority of the Orthodox and the ultra-Orthodox are also not militant zealots. Not yet. But they will become increasingly extreme as their demographic heft morphs into a critical mass and consolidates their lordship. We have a few years of grace left between the secular hegemony of the past and the – still preventable – religious hegemony of the future. These will be years in which a cultural and perhaps also political alliance can be forged among the secular, traditional, Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Israelis who share a view of Judaism as a living entity and wish to realize it in all the spheres of life from which it has been rabbinically excluded. A window of opportunity has been opened for cooperation between secular folk looking for roots and religious folk longing for the renewal of halakha – Jewish religious law. The question is whether we will act before the window closes.

Those who read the first Guttman Center survey on this topic, in 1991, were disillusioned early on about the “secular majority.” That’s because 56 percent of those asked at the time said, for example, that they believe wholeheartedly that the Torah is God-given (that 56 percent has now become 65 percent in the new survey ). The second survey, conducted in 1999, seemed to show that the erosion of the “secular majority” had been contained. In fact, that temporary turnabout was due to the mass migration from the former Soviet Union. That gave the Israeli body politic a secular blood transfusion for a few years, until the newcomers integrated into Israeli society and became traditional like the majority of Israeli Jews.

In other words, the wave of migration of the 1990s did not save the “secular majority,” but only bought it time in its rearguard battle. In the meantime, right under the nose of this so-called majority, the Haredim and the Orthodox continued to be fruitful and multiply, and waxed exceeding mighty. As the executive summary of the new survey notes, “It is plausible that were it not for the mass immigration from the former Soviet Union beginning in the early 1990s, the increase in affinity to tradition and religion from 1991 to 2009 would have been constant.”

Those are the findings, but the representatives of the “secular majority” are not confused by the facts. Take, for example, the poet Natan Zach, a prominent figure in Israeli secularism. “I don’t think this country will last,” he told the newspaper Maariv recently. “The society has disintegrated into fragments … This nation has disintegrated into partisan factions permeated by hatred and zealousness … It can’t last.”

But what held it together in the past, before the society Zach’s answer might surprise his secular admirers. “The absence of a common base,” he says, is what bothers him most of all. “”disintegrated into fragments”?The common bases – religion, history, remembrance of Zion, the Western Wall and the symbols that helped us perceive ourselves as one nation, which succeeded in shaping a Jewish image in the face of Christianity – all of those things disappeared. We actually have nothing.”

Forthright words. But who would have believed that a secular leftist like Zach would invoke “religion, history, remembrance of Zion, the Western Wall and the symbols that helped us perceive ourselves as one nation” as our common ground?

Take note: It is this common ground, not the melting pot of the Ben-Gurion era, for which Zach now waxes nostalgic. Indeed, he dissociates himself from Ben-Gurion, who “thought that if you take different people from different faiths, from other parts of the world, from diverse traditions and cultures and put them all into the grinder in which our parents used to make meatballs, everyone comes out the same.” Sixty years late, Zach acknowledges the baseless notion of the artificial melting pot, which demanded that non-secular Jews convert their concrete Jewish identity into a bland civil “Israeli” identity in the Tel Aviv sense of the word.

What Zach grasps now was understood 50 years before Israel’s establishment by Ahad Ha’am (Asher Ginsberg ), Hayim Nahman Bialik and the other cultural Zionists. Though they had a high regard for the initiative advocated by Theodor Herzl, they maintained that Zionism would not solve the Jewish question if it did not address the question of Judaism. Would the Jews in their state live by the lights of their distinctive culture, Ahad Ha’am wondered in 1903, “or will the state be no more than a European colony in Asia,” as Herzl’s vision suggested? If the Jewish state was not destined to arise “on the foundation of the eternal bond between the past and the future,” why insist on the Land of Israel, or on speaking Hebrew? Let the inhabitants of the Jewish state speak French (the lingua franca at the time of the first wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine, 1882-1903 ), or German (as Herzl, whose native language it was, suggested ).

Secular and spiritual

“We want to create an autonomous life here, which has its own features and special character,” Bialik declared in 1928, at the cornerstone-laying ceremony for the Ohel Shem cultural center in Tel Aviv, adding, “In order to create original and true ways of life which bear a national aspect, the material for their creation must be taken from the foundation stones of the ancient ways of life.”

Ahad Ha’am and Bialik were concerned that the Jewish state would not endure without a cultural base common to religious and secular: Hebrew, the Bible, the land, history, the legends of the ancient Jewish sages, classic and modern Hebrew literature, the Jewish festivals, the passages of life and the symbols. They proposed a free Judaism, not freedom from Judaism. They proposed that we live Judaism not as a religion that had congealed, not as a rabbinical package deal brokered back when Jewish men were forbidden to listen to women singing, but as a resurgent and relevant national culture. They offered us the common Jewish base whose loss Natan Zach is now remembering to lament.

The same approach was taken by the most prominent of the founders of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “It is not destined for the state that will arise to be a state of Jews, but a true Jewish state,” the philosopher Martin Buber said in 1918. “I doubt that the secular ideal is capable of remaining strong for very long,” the first rector of the new university, Samuel Hugo Bergman, stated in 1936, in remarks made at the start of the new academic year. The reason, he explained, was that the social and national ideals advocated by the various Zionist parties “are no more than forms derived from the comprehensive ideal of the Jewish people: to repair the world under the sovereignty of God.” And Bergman was being gentle in comparison to Gershom Scholem, the scholar of the kabbala, who said in 1970 that “the severing of the living connection to the heritage of the generations is educational murder,” and that “the State of Israel possesses value only because of the consciousness of Jewish continuity.”

The spiritual leaders of the labor movement also wished to fashion a rooted national culture here, one not detached from its Jewish sources. “If the Jewish people will only be dragged in the wake of others, if what is created here will be only a Hebrew translation of European life, it will not be sustainable,” A.D. Gordon wrote in 1920; and 20 years later Berl Katznelson added, “For a great many of those who are coming to us, or who are being brought to our shores from far as well as near (and, I fear, for no few of those who are being brought up here or were born here ) those shores have not yet become home. Our educational mission is to turn this land, and the spiritual world which gave birth to it, into a home for them, to which the soul clings and abides. That will not be achieved without an atmosphere of love with no scores to settle, respect without falsity, attachment to the nation and its destiny and to its tragic history, its spiritual values, its living creation and the vision of its revival.”

Yitzhak Tabenkin, the spiritual leader of the Kibbutz Hameuhad movement, said in 1928, “Not to be moved by Tisha B’Av is barbarism.” Meir Yaari, the spiritual mentor of the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair movement, wrote in 1923, “One thing only is clear to me: that a whole nation cannot continue to exist for long without a metaphysical principle and a religious symbol. Otherwise, it will decline. And no economic and social conception will help here.”

If we want the native-born Israeli to understand what he is doing here, “we must implant in him the Jewish consciousness which draws on the great spiritual heritage of the Jewish people, on the riveting destiny shared, knowingly or not, by all parts of the Jewish people wherever they may be, and on the messianic vision, the vision of Jewish and human redemption imparted to us by the biblical prophets,” the prime minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, wrote in 1956 in his cabin at Kibbutz Sde Boker.

No economic or social concept will render us a nation, nor will any civil concept void of identity. Social solidarity is dependent on national-cultural solidarity. Only social consciousness anchored in the biblical concepts of social justice, in the community-based sensitivity of the Jewish sages, in the precepts of charity propounded by Maimonides and in a sense of belonging to this nation and to its history; only a conception of Judaism as a dynamic culture to which each of us is invited to contribute his share; only this will make it possible for secular, Orthodox and Haredi, and also for the Arabs who dwell among us, to speak to one other and not only about one another.

Dr. Assaf Inbari is a novelist and the author of “Home” (2009), which tells the story of a kibbutz.