Nazareth was the one Palestinian

city in Israel whose inhabitants were not evicted in the Naqba. Jonathan Cook tells the fascinating story of

why Nazareth’s inhabitants escaped the massacres and expulsions. He also tells the story of how Upper Nazareth

was founded, as a way of confining and suffocating Nazareth. In Upper Nazareth today, founded a Jewish only

city, the Mayor Shimon Gapso has banned the celebration

of Christmas.

city in Israel whose inhabitants were not evicted in the Naqba. Jonathan Cook tells the fascinating story of

why Nazareth’s inhabitants escaped the massacres and expulsions. He also tells the story of how Upper Nazareth

was founded, as a way of confining and suffocating Nazareth. In Upper Nazareth today, founded a Jewish only

city, the Mayor Shimon Gapso has banned the celebration

of Christmas.

|

| Christmas in Nazareth |

Israels

+972 Magazine reports how, when Palestinian residents approached Gapso, and requested that a Christmas

tree be put up, since there were 3 large menorahs (candelabrums) erected to

celebrate the Jewish festival of Chanukah, Gapso, reports Israeli news site NRG

(owned by Maariv), refused. “Upper

Nazareth is a Jewish town and all its symbols are Jewish., As long as I hold

office, no non-Jewish symbol will be presented in the city.”

|

| modern Nazareth |

In

2010 Gapso proclaimed that the public display of the Christian symbol as

provocative and banned Xmas trees from public squares. “Nazareth Illit is a Jewish city and it will

not happen — not this year and not next year, so long as I am a mayor”.

2010 Gapso proclaimed that the public display of the Christian symbol as

provocative and banned Xmas trees from public squares. “Nazareth Illit is a Jewish city and it will

not happen — not this year and not next year, so long as I am a mayor”.

Racism? Perish the thought.

|

| Moshe Sharett, Israel’s Prime Minister and Amin Gargurah, Mayor of Nazareth |

Why Israel has silenced the 1948 story of Nazareth’s survival

12

January 2016

January 2016

A

rarely told story of the 1948 war that founded Israel concerns Nazareth’s

survival. It is the only Palestinian city in what is today Israel that was not

ethnically cleansed during the year-long fighting. Other cities, such as Jaffa,

Lydd, Ramleh, Haifa and Acre, now have small Palestinian populations that

mostly live in ghetto-like conditions in what have become Jewish cities. Still

others, like Tiberias and Safad, have no Palestinians left in them at all.

rarely told story of the 1948 war that founded Israel concerns Nazareth’s

survival. It is the only Palestinian city in what is today Israel that was not

ethnically cleansed during the year-long fighting. Other cities, such as Jaffa,

Lydd, Ramleh, Haifa and Acre, now have small Palestinian populations that

mostly live in ghetto-like conditions in what have become Jewish cities. Still

others, like Tiberias and Safad, have no Palestinians left in them at all.

|

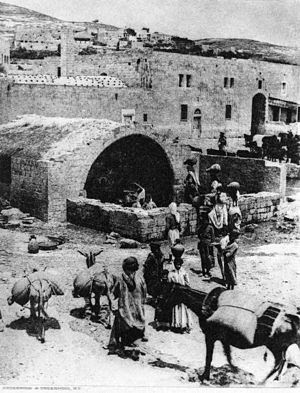

| Historic photo of Mary’s Well |

Nazareth

was not only an anomaly; it was a mistake. It was supposed to be cleared of its

Palestinian population, just like those other Palestinian cities now in Israel.

Much to Israel’s regret, it has become an unofficial capital for Israel’s 1.6

million Palestinian citizens, a fifth of the Israeli population.

was not only an anomaly; it was a mistake. It was supposed to be cleared of its

Palestinian population, just like those other Palestinian cities now in Israel.

Much to Israel’s regret, it has become an unofficial capital for Israel’s 1.6

million Palestinian citizens, a fifth of the Israeli population.

The

reason for Nazareth’s survival are the actions of one individual. Ben

Dunkelman, a Canadian Jew who was the commander of the Israeli army’s Seventh

Armoured Brigade, disobeyed orders to expel Nazareth’s residents.

reason for Nazareth’s survival are the actions of one individual. Ben

Dunkelman, a Canadian Jew who was the commander of the Israeli army’s Seventh

Armoured Brigade, disobeyed orders to expel Nazareth’s residents.

|

| Church in Nazareth on site of Joseph’s workshop, 1891 |

Dunkelman’s

role has been largely obscured in the historical record – and for good reason.

Israel would prefer that observers make an unjustified assumption: that

“Christian” Nazareth survived, unlike other Palestinian cities, because its

leaders were less militant or because they preferred to surrender. Dunkelman’s

story proves that was not the case.

role has been largely obscured in the historical record – and for good reason.

Israel would prefer that observers make an unjustified assumption: that

“Christian” Nazareth survived, unlike other Palestinian cities, because its

leaders were less militant or because they preferred to surrender. Dunkelman’s

story proves that was not the case.

It

is therefore a welcome development that a major Canadian newspaper, the Toronto

Star, has revisited Dunkelman’s role in Nazareth, even if its reporter, Mitch

Potter, has contributed in his own way to the mythologising of Dunkelman in an

article headlined: “The Toronto man who saved Nazareth”.

is therefore a welcome development that a major Canadian newspaper, the Toronto

Star, has revisited Dunkelman’s role in Nazareth, even if its reporter, Mitch

Potter, has contributed in his own way to the mythologising of Dunkelman in an

article headlined: “The Toronto man who saved Nazareth”.

|

| Xmas tree banned in Nazareth Illit |

Excised memories

It

is worth bearing in mind, when we consider the attacks on Palestinian cities in

1948, how sensitive these matters were for Israel. Both Dunkelman and another

commander, Yitzhak Rabin, who would later become a prime minister, wrote

memoirs that included their experiences of the 1948 war.

is worth bearing in mind, when we consider the attacks on Palestinian cities in

1948, how sensitive these matters were for Israel. Both Dunkelman and another

commander, Yitzhak Rabin, who would later become a prime minister, wrote

memoirs that included their experiences of the 1948 war.

Under

pressure from the Israeli military authorities, both excised from their

accounts the sections they had written dealing with the attacks on the

Palestinian cities they were responsible for attacking. That was because those

accounts were the proof, long denied by Israel and its supporters, that the Israeli

leadership had intended and carried out the ethnic cleansing of most of the

Palestinian population during 1948.

pressure from the Israeli military authorities, both excised from their

accounts the sections they had written dealing with the attacks on the

Palestinian cities they were responsible for attacking. That was because those

accounts were the proof, long denied by Israel and its supporters, that the Israeli

leadership had intended and carried out the ethnic cleansing of most of the

Palestinian population during 1948.

|

| Crusader-era carving in Nazareth |

Some

750,000 Palestinians – out of 900,000 living inside the borders of what was to

become the new Jewish state – were forced out and refused the right to return.

In fact, the expulsion rate was far higher than the ostensible 80 per cent

figure. Under pressure from the Vatican, Israel allowed many Christian refugees

back; it did a land swap with Jordan in 1949 that brought more than 30,000 Palestinians

into the new state; and many Palestinian refugees managed to sneak back to

surviving communities like Nazareth and blend in with the local population in

preparation for what they hoped would be their return to their villages.

750,000 Palestinians – out of 900,000 living inside the borders of what was to

become the new Jewish state – were forced out and refused the right to return.

In fact, the expulsion rate was far higher than the ostensible 80 per cent

figure. Under pressure from the Vatican, Israel allowed many Christian refugees

back; it did a land swap with Jordan in 1949 that brought more than 30,000 Palestinians

into the new state; and many Palestinian refugees managed to sneak back to

surviving communities like Nazareth and blend in with the local population in

preparation for what they hoped would be their return to their villages.

Rabin

led the attack on the Palestinian cities of Lydd and Ramleh, near Tel Aviv and

today the mostly Jewish cities of Lod and Ramla. According to the missing

section of his autobiography, later publicised in the New York Times, Rabin asked David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime

minister, what to do with the 50,000 inhabitants of Lydd and Ramleh. Rabin

recounted: “Ben Gurion waved his hand in a gesture that said: ‘Drive them

out!’” Rabin did exactly that, after a terrible massacre of hundreds of

residents who were sheltering in a local mosque.

led the attack on the Palestinian cities of Lydd and Ramleh, near Tel Aviv and

today the mostly Jewish cities of Lod and Ramla. According to the missing

section of his autobiography, later publicised in the New York Times, Rabin asked David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime

minister, what to do with the 50,000 inhabitants of Lydd and Ramleh. Rabin

recounted: “Ben Gurion waved his hand in a gesture that said: ‘Drive them

out!’” Rabin did exactly that, after a terrible massacre of hundreds of

residents who were sheltering in a local mosque.

|

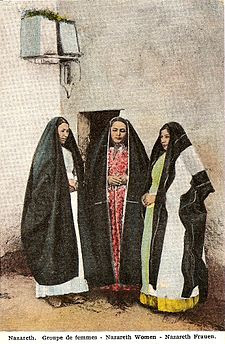

| Old postcard of Nazareth women |

Ben

Gurion, as the Israeli historian of the period Ilan Pappe has noted in his book

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, was careful not to leave a paper trail

showing that he had ordered the expulsion of Palestinians. Instead, Israel

would promote the myth that the Palestinian population had been ordered by

neighbouring Arab leaders to flee.

Gurion, as the Israeli historian of the period Ilan Pappe has noted in his book

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, was careful not to leave a paper trail

showing that he had ordered the expulsion of Palestinians. Instead, Israel

would promote the myth that the Palestinian population had been ordered by

neighbouring Arab leaders to flee.

|

| The Skylight of Modern Nazareth |

Relieved of command

We

do not know if Dunkelman had a similar meeting with Ben Gurion. What we do

know, and the Star’s account confirms, is that it had been made clear to

Dunkelman that he was supposed to expel the inhabitants of Nazareth. Dunkelman

disobeyed, and allowed the city to surrender. He was relieved of his command in

Nazareth a day later.

do not know if Dunkelman had a similar meeting with Ben Gurion. What we do

know, and the Star’s account confirms, is that it had been made clear to

Dunkelman that he was supposed to expel the inhabitants of Nazareth. Dunkelman

disobeyed, and allowed the city to surrender. He was relieved of his command in

Nazareth a day later.

|

| Russian pilgrims approaching Nazareth. circa 1904 |

The

Star reports on a page referring to the attack on Nazareth that was removed

from Dunkelman’s 1976 memoir, Dual Allegiance. We know about it only because

his ghostwriter, the late Israeli journalist Peretz Kidron, tried to interest

the New York Times in Dunkelman’s story, as a counterpart to Rabin’s. The Times

published the Rabin story but ignored Dunkelman’s.

Star reports on a page referring to the attack on Nazareth that was removed

from Dunkelman’s 1976 memoir, Dual Allegiance. We know about it only because

his ghostwriter, the late Israeli journalist Peretz Kidron, tried to interest

the New York Times in Dunkelman’s story, as a counterpart to Rabin’s. The Times

published the Rabin story but ignored Dunkelman’s.

Interestingly,

Dunkelman kept the account of his role in the Nazareth attack so quiet that,

according to their quotes in the Star, neither his son nor his publisher at

Macmillan knew about it.

Dunkelman kept the account of his role in the Nazareth attack so quiet that,

according to their quotes in the Star, neither his son nor his publisher at

Macmillan knew about it.

Dunkelman

writes that he was “shocked and horrified” at the order to depopulate Nazareth.

He told his superior, Haim Laskov: “I would do nothing of the sort.” He

demanded that his replacement give his “word of honour” that the inhabitants

would be allowed to stay, and concludes: “It seems that my disobedience did

have some effect … It seems to have given the high command time for second

thoughts, which led them to the conclusion that it would indeed be wrong to

expel. There was never any more talk of the evacuation plan, and the city’s

Arab citizens have lived there ever since.”

writes that he was “shocked and horrified” at the order to depopulate Nazareth.

He told his superior, Haim Laskov: “I would do nothing of the sort.” He

demanded that his replacement give his “word of honour” that the inhabitants

would be allowed to stay, and concludes: “It seems that my disobedience did

have some effect … It seems to have given the high command time for second

thoughts, which led them to the conclusion that it would indeed be wrong to

expel. There was never any more talk of the evacuation plan, and the city’s

Arab citizens have lived there ever since.”

|

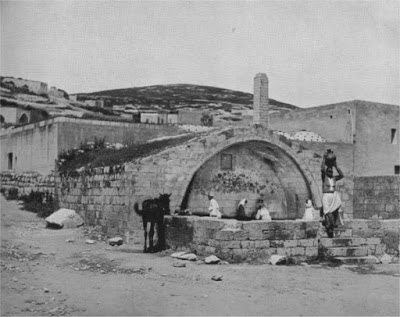

| Nazareth-The-Fountain-of-the-Virgin-1894 |

‘Swallowing’ Nazareth

In

fact, we know what those “second thoughts” were. Stripped of a pretext to

justify expulsions from Nazareth in the supposed “heat of battle”, Ben Gurion

came up with Plan B (or maybe it was Plan E, given that the ethnic cleansing

was inspired by Plan Dalet, or D in Hebrew).

fact, we know what those “second thoughts” were. Stripped of a pretext to

justify expulsions from Nazareth in the supposed “heat of battle”, Ben Gurion

came up with Plan B (or maybe it was Plan E, given that the ethnic cleansing

was inspired by Plan Dalet, or D in Hebrew).

In

the wake of the 1948 war, during a near two-decade period of military

government imposed on Israel’s new Palestinian minority, Ben Gurion decided to

establish Nazareth Ilit (Upper Nazareth) almost on top of Nazareth. It was the

flagship of his “Judaisation of the Galilee” campaign. Ben Gurion was aghast

not only that Nazareth had survived, but that it had doubled in size as

thousands of refugees from surrounding villages fled to it seeking sanctuary.

the wake of the 1948 war, during a near two-decade period of military

government imposed on Israel’s new Palestinian minority, Ben Gurion decided to

establish Nazareth Ilit (Upper Nazareth) almost on top of Nazareth. It was the

flagship of his “Judaisation of the Galilee” campaign. Ben Gurion was aghast

not only that Nazareth had survived, but that it had doubled in size as

thousands of refugees from surrounding villages fled to it seeking sanctuary.

According

to Israeli state archives, Michael Michael, the military governor for Nazareth

in this period, stated that the goal of Nazareth Ilit was to “swallow up”

Nazareth. In short, Israel hoped retrospectively to destroy Nazareth as a

Palestinian city, transforming it into another Lydd. The Jewish city of

Nazareth Ilit would become with the main city, with Nazareth its own shadow

ghetto. Despite Israel’s best efforts, it largely failed in this goal, not

least because it struggled to attract Israeli Jews to live next to a large

Palestinian population .

to Israeli state archives, Michael Michael, the military governor for Nazareth

in this period, stated that the goal of Nazareth Ilit was to “swallow up”

Nazareth. In short, Israel hoped retrospectively to destroy Nazareth as a

Palestinian city, transforming it into another Lydd. The Jewish city of

Nazareth Ilit would become with the main city, with Nazareth its own shadow

ghetto. Despite Israel’s best efforts, it largely failed in this goal, not

least because it struggled to attract Israeli Jews to live next to a large

Palestinian population .

|

| Nazareth, 1842 |

Why

was it so important for the Israeli leadership to destroy Nazareth? Because

they feared that a Palestinian city – with its intellectuals, political

activists, and advanced education system under the control of international

Christian institutions – might encourage the emergence of an effective

resistance, one that would be able to mount opposition to a state privileging

Jews. Such a political and cultural capital might articulate to the outside

world exactly what Israel was up to in Judaising places with large Palestinian

populations like the Galilee.

was it so important for the Israeli leadership to destroy Nazareth? Because

they feared that a Palestinian city – with its intellectuals, political

activists, and advanced education system under the control of international

Christian institutions – might encourage the emergence of an effective

resistance, one that would be able to mount opposition to a state privileging

Jews. Such a political and cultural capital might articulate to the outside

world exactly what Israel was up to in Judaising places with large Palestinian

populations like the Galilee.

Mortar barrages

The

Toronto Star’s starry-eyed account of Dunkelman includes the following

observation: “He won no medals for refusing to molest civilians [in Nazareth],

nor any credit from his Israeli superiors.” He is painted as a man who stuck

close to the rules of war and avoided hurting civilians wherever possible in a

series of “almost bloodless” attacks.

Toronto Star’s starry-eyed account of Dunkelman includes the following

observation: “He won no medals for refusing to molest civilians [in Nazareth],

nor any credit from his Israeli superiors.” He is painted as a man who stuck

close to the rules of war and avoided hurting civilians wherever possible in a

series of “almost bloodless” attacks.

But

in fact, as the Star notes in passing, Dunkelman’s chief military talent was

for making innovative use of “concentrated mortar barrages”, a skill he learnt

during the Second World War. In other words, he was an expert at firing large

numbers of imprecise shells into populated areas, inevitably killing and

wounding civilians.

in fact, as the Star notes in passing, Dunkelman’s chief military talent was

for making innovative use of “concentrated mortar barrages”, a skill he learnt

during the Second World War. In other words, he was an expert at firing large

numbers of imprecise shells into populated areas, inevitably killing and

wounding civilians.

Two

Canadians have published posts making important criticisms of the Star’s

account.

Canadians have published posts making important criticisms of the Star’s

account.

Peter

Larson, chair of Canada’s National Education Committee on Israel-Palestine, points out that the operation in July 1948 led by Dunkelman was

an attack on communities like Nazareth that were supposed to be firmly part of

an Arab state under the terms of the United Nations Partition Plan, set out

nine months earlier. As Larson writes, “Nazareth was forcibly incorporated into

the new State of Israel contrary to the UN plan and despite the wishes of its

residents.”

Larson, chair of Canada’s National Education Committee on Israel-Palestine, points out that the operation in July 1948 led by Dunkelman was

an attack on communities like Nazareth that were supposed to be firmly part of

an Arab state under the terms of the United Nations Partition Plan, set out

nine months earlier. As Larson writes, “Nazareth was forcibly incorporated into

the new State of Israel contrary to the UN plan and despite the wishes of its

residents.”

|

| Palestinian children play outside Deir Latin church in Gaza |

Protection for Christians

There

is archival evidence to suggest that Dunkelman believed Christian Palestinians

needed protecting, a view he did not extend to Muslim Palestinians.

is archival evidence to suggest that Dunkelman believed Christian Palestinians

needed protecting, a view he did not extend to Muslim Palestinians.

Israeli

historian Benny Morris notes a cable from Dunkelman as his troops marched

through the Galilee in November 1948: “I protest against the eviction of

Christians from the village of Rama and its environs. We saw Christians at Rama

in the fields thirsty for water and suffering from robbery. Other brigades

expelled Christians from villages that did not resist and surrendered to our

forces. I suggest that you issue an order to return the Christians to their

villages.”

historian Benny Morris notes a cable from Dunkelman as his troops marched

through the Galilee in November 1948: “I protest against the eviction of

Christians from the village of Rama and its environs. We saw Christians at Rama

in the fields thirsty for water and suffering from robbery. Other brigades

expelled Christians from villages that did not resist and surrendered to our

forces. I suggest that you issue an order to return the Christians to their

villages.”

Morris

mentions that under the influence of Dunkelman, among others, the Israeli

army’s guidelines on the expulsion of Christian Palestinians changed over time.

mentions that under the influence of Dunkelman, among others, the Israeli

army’s guidelines on the expulsion of Christian Palestinians changed over time.

In

contrast to his decision to protect Nazareth and Christians, Dunkelman and his

soldiers were ruthless in driving out Palestinians from many of the more than

500 Palestinian communities razed by Israel in 1948 and afterwards.

contrast to his decision to protect Nazareth and Christians, Dunkelman and his

soldiers were ruthless in driving out Palestinians from many of the more than

500 Palestinian communities razed by Israel in 1948 and afterwards.

War crimes

In

Saffuriya, a large Muslim village a few kilometres from Nazareth that was

attacked by the Seventh Brigade a day earlier, barrel bombs were dropped on the

village as the residents were at home breaking that day’s Ramadan fast. All of

Saffuriya’s inhabitants were driven out, and their homes destroyed. Today it is

an exclusively Jewish farming community called Tzipori.

Saffuriya, a large Muslim village a few kilometres from Nazareth that was

attacked by the Seventh Brigade a day earlier, barrel bombs were dropped on the

village as the residents were at home breaking that day’s Ramadan fast. All of

Saffuriya’s inhabitants were driven out, and their homes destroyed. Today it is

an exclusively Jewish farming community called Tzipori.

Without

a doubt, Dunkelman directly participated in the mass expulsion of many tens of

thousands of Palestinian civilians from their homes – a war crime by the laws

of war that had recently emerged in the wake of the Second World War. He also

admitted in his memoir that he allowed his troops to loot Palestinian property,

another war crime.

a doubt, Dunkelman directly participated in the mass expulsion of many tens of

thousands of Palestinian civilians from their homes – a war crime by the laws

of war that had recently emerged in the wake of the Second World War. He also

admitted in his memoir that he allowed his troops to loot Palestinian property,

another war crime.

But,

while he does not refer to them in Dual Allegiance, Dunkelman is also

implicated in some of the more notorious Israeli massacres of Palestinians in

1948.

while he does not refer to them in Dual Allegiance, Dunkelman is also

implicated in some of the more notorious Israeli massacres of Palestinians in

1948.

In

the worst case, in the village of Safsaf, north of Safad, notes

Canadian journalist Dan Freeman-Moloy, Dunkelman had command responsibility as

he led Operation Hiram in late October 1948. His troops’ behaviour in Safsaf

and elsewhere is made clear in documents in Israel’s military archives

uncovered by Morris for his book The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem.

the worst case, in the village of Safsaf, north of Safad, notes

Canadian journalist Dan Freeman-Moloy, Dunkelman had command responsibility as

he led Operation Hiram in late October 1948. His troops’ behaviour in Safsaf

and elsewhere is made clear in documents in Israel’s military archives

uncovered by Morris for his book The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem.

Drawing

on a declassified briefing from November 1948 by Israel Galili, Ben Gurion’s

number two in the defence ministry, Morris writes of the actions of Dunkelman’s

troops:

on a declassified briefing from November 1948 by Israel Galili, Ben Gurion’s

number two in the defence ministry, Morris writes of the actions of Dunkelman’s

troops:

“At

Saliha it appears that troops blew up a house, possibly the village mosque,

killing 60-94 persons who had been crowded into it. In Safsaf, troops shot and

then dumped into a well 50-70 villagers and POWs [prisoners of war]. In Jish,

the troops apparently murdered about 10 Moroccan POWs (who had served with the

Syrian Army) and a number of civilians, including, apparently, four Maronite

Christians, and a woman and her baby.”

Saliha it appears that troops blew up a house, possibly the village mosque,

killing 60-94 persons who had been crowded into it. In Safsaf, troops shot and

then dumped into a well 50-70 villagers and POWs [prisoners of war]. In Jish,

the troops apparently murdered about 10 Moroccan POWs (who had served with the

Syrian Army) and a number of civilians, including, apparently, four Maronite

Christians, and a woman and her baby.”

Morris

concluded: “These atrocities, mostly committed against Muslims, no doubt

precipitated the flight of communities on the path of the IDF advance. … What

happened at Safsaf and Jish no doubt reached the villagers of Ras al Ahmar,

‘Alma, Deishum and al Malikiya hours before the Seventh Brigade’s columns.

These villages, apart from ‘Alma, seem to have been completely or largely empty

when the IDF arrived.”

concluded: “These atrocities, mostly committed against Muslims, no doubt

precipitated the flight of communities on the path of the IDF advance. … What

happened at Safsaf and Jish no doubt reached the villagers of Ras al Ahmar,

‘Alma, Deishum and al Malikiya hours before the Seventh Brigade’s columns.

These villages, apart from ‘Alma, seem to have been completely or largely empty

when the IDF arrived.”

Dunkelman

can no doubt take credit for Nazareth’s survival. But a full and proper

historical accounting is still needed of the war crimes committed not only by

Dunkelman but by those he answered to.

can no doubt take credit for Nazareth’s survival. But a full and proper

historical accounting is still needed of the war crimes committed not only by

Dunkelman but by those he answered to.

Posted in Blog