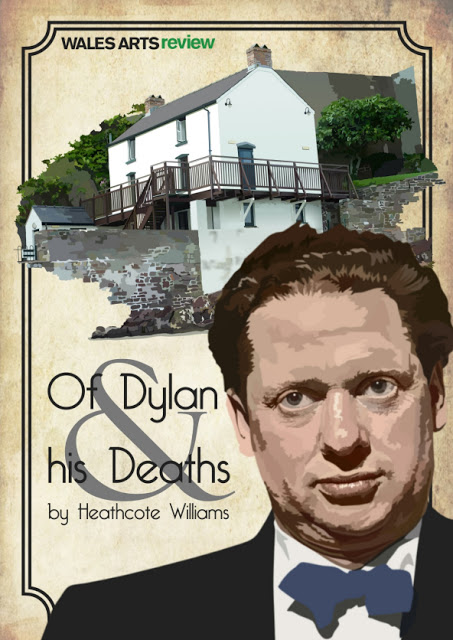

It’s not often that you read a profoundly brilliant and

moving essay such as that by Heathcote Amory. Musically Bob Dylan is one

of my favourite heroes but, as the essay below shows, he is also a deeply flawed

hero. Dylan is accused of plagiarism,

not I think always fairly, given it is well known that he takes as his

inspiration many influences. Folk music

has always been a progressive development resting on the output and memory of

previous generations.

moving essay such as that by Heathcote Amory. Musically Bob Dylan is one

of my favourite heroes but, as the essay below shows, he is also a deeply flawed

hero. Dylan is accused of plagiarism,

not I think always fairly, given it is well known that he takes as his

inspiration many influences. Folk music

has always been a progressive development resting on the output and memory of

previous generations.

However the accusation that he has sold out politically and

prostituted himself to commercial and right-wing political interests is spot

on. His earlier support, which he never

disavowed, for the Jewish Nazi Rabbi

Meir Kahane of the Kach party, was and is unforgiveable. His playing in Israel and his atrocious song Neighbourhood Bully on the

Infidels album, which portrayed Israel as the victim of bullying by its

neighbourhood, is racist nonsense.

Perhaps the Lebanese, who saw 20,000 die and a further 100,000 wounded,

in addition to mass devastation in 1982, had also been guilty of this crime.

prostituted himself to commercial and right-wing political interests is spot

on. His earlier support, which he never

disavowed, for the Jewish Nazi Rabbi

Meir Kahane of the Kach party, was and is unforgiveable. His playing in Israel and his atrocious song Neighbourhood Bully on the

Infidels album, which portrayed Israel as the victim of bullying by its

neighbourhood, is racist nonsense.

Perhaps the Lebanese, who saw 20,000 die and a further 100,000 wounded,

in addition to mass devastation in 1982, had also been guilty of this crime.

Dylan’s comparison between the poetic genius Dylan Thomas

and himself, the person who stole Thomas’s name, by suggesting that he had done

more for Dylan Thomas than the other way round, was as absurd as it was

offensive. It was Dylan who had filched

Thomas’s poetry for his songs as well as his persona. Given Dylan Thomas had died in 1953 it is

difficult to understand how he could have benefited from Dylan. A combination of egomania and narcissism.

and himself, the person who stole Thomas’s name, by suggesting that he had done

more for Dylan Thomas than the other way round, was as absurd as it was

offensive. It was Dylan who had filched

Thomas’s poetry for his songs as well as his persona. Given Dylan Thomas had died in 1953 it is

difficult to understand how he could have benefited from Dylan. A combination of egomania and narcissism.

Tony Greenstein

|

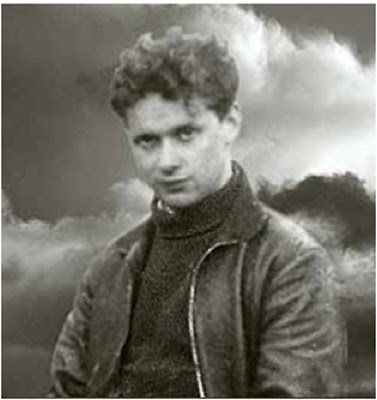

| Dylan Thomas ©Jeff Towns/DBC |

As a

reward for my having learnt William Blake’s poem ‘Tyger, Tyger’ and for having

precociously recited it to him without stumbling, my father promised to take me

to hear Dylan Thomas reading at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

reward for my having learnt William Blake’s poem ‘Tyger, Tyger’ and for having

precociously recited it to him without stumbling, my father promised to take me

to hear Dylan Thomas reading at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

I was

nine. “Your treat,” he said. “He’s a poet. He’s Welsh.”

nine. “Your treat,” he said. “He’s a poet. He’s Welsh.”

He was in

the habit of taking me to things that he considered to be “improving” events

such as Emlyn Williams’ one-man show based on Charles’ Dickens’ public

readings; or to Shakespeare plays at the Old Vic, and from my earliest

childhood my father encouraged me to learn and recite poems.

the habit of taking me to things that he considered to be “improving” events

such as Emlyn Williams’ one-man show based on Charles’ Dickens’ public

readings; or to Shakespeare plays at the Old Vic, and from my earliest

childhood my father encouraged me to learn and recite poems.

At his

behest I was urged to learn a lot of Blake off by heart and most of Kipling’s

‘If’. I learned one of W.S. Gilbert’s ‘Bab Ballads’ (the one about

cannibalism), Gray’s Elegy, W. E, Henley’s ‘Invictus’ and a few scraps from the

Welsh epic, The Mabinogion, of which my father had a fine copy with a gold

embossed cover.

behest I was urged to learn a lot of Blake off by heart and most of Kipling’s

‘If’. I learned one of W.S. Gilbert’s ‘Bab Ballads’ (the one about

cannibalism), Gray’s Elegy, W. E, Henley’s ‘Invictus’ and a few scraps from the

Welsh epic, The Mabinogion, of which my father had a fine copy with a gold

embossed cover.

He’d also

demand that I’d join him in reciting the seasonal, “It was Christmas Day in the

workhouse/the one day of the year/In came the workhouse master/his belly full

of beer…” as well as that lengthy music-hall standard ‘Albert and the Lion’, a

narrative poem that ends in tragedy thanks to a small boy at Blackpool Zoo

having been somewhat too curious about the Zoo’s star attraction, an elderly

lion called Wallace.

demand that I’d join him in reciting the seasonal, “It was Christmas Day in the

workhouse/the one day of the year/In came the workhouse master/his belly full

of beer…” as well as that lengthy music-hall standard ‘Albert and the Lion’, a

narrative poem that ends in tragedy thanks to a small boy at Blackpool Zoo

having been somewhat too curious about the Zoo’s star attraction, an elderly

lion called Wallace.

Henley’s

‘Invictus’ begins: ‘Out of the night that covers me, /Black as the Pit from

pole to pole, /I thank whatever gods may be /For my unconquerable soul.” And my

father would boom it out whenever he felt disheartened or blown off course and

he encouraged me to copy him, line by line.

‘Invictus’ begins: ‘Out of the night that covers me, /Black as the Pit from

pole to pole, /I thank whatever gods may be /For my unconquerable soul.” And my

father would boom it out whenever he felt disheartened or blown off course and

he encouraged me to copy him, line by line.

My father

had a small study off the landing in our house and as I ran up and downstairs

I’d sometimes hear him regale himself with the poem as a tonic to bolster up

his spirits. ‘Black as the pit from pole to pole, I am the master of my fate.”

he’d roar with a thundering Welsh undulation, “I am the captain of my

soul.’ He seemed to feel that the poem was an indispensible remedy for

all spiritual ailments and he consequently insisted on my committing it to

memory.

had a small study off the landing in our house and as I ran up and downstairs

I’d sometimes hear him regale himself with the poem as a tonic to bolster up

his spirits. ‘Black as the pit from pole to pole, I am the master of my fate.”

he’d roar with a thundering Welsh undulation, “I am the captain of my

soul.’ He seemed to feel that the poem was an indispensible remedy for

all spiritual ailments and he consequently insisted on my committing it to

memory.

“In the

fell clutch of circumstance/I have not winced nor cried aloud./Under the

bludgeonings of chance /My head is bloody, but unbowed.”

fell clutch of circumstance/I have not winced nor cried aloud./Under the

bludgeonings of chance /My head is bloody, but unbowed.”

Henley’s

poem was essentially a high-minded precursor of that now ubiquitous and

mawkishly self-regarding song, ‘I did it my way’ but my father was passionate

about it and when I knew all the verses, he’d poultice them out of me on the

mystifying walks he took me on; mystifying because when I asked, “Where

are we going?” his unvarying response would be, “There and back.”

poem was essentially a high-minded precursor of that now ubiquitous and

mawkishly self-regarding song, ‘I did it my way’ but my father was passionate

about it and when I knew all the verses, he’d poultice them out of me on the

mystifying walks he took me on; mystifying because when I asked, “Where

are we going?” his unvarying response would be, “There and back.”

With his

children he was largely silent save for this enthusiasm for poetry. The

walks were conducted with his being entirely lost in thought except for

recitations of a poem by him or by me at his prodding. He’d say, ‘Give us

the tiger,’ and so I’d do Blake’s ‘Tyger’ which, due to his insistence,

had been burning brightly in my mind since I was more or less out of a

high-chair.

children he was largely silent save for this enthusiasm for poetry. The

walks were conducted with his being entirely lost in thought except for

recitations of a poem by him or by me at his prodding. He’d say, ‘Give us

the tiger,’ and so I’d do Blake’s ‘Tyger’ which, due to his insistence,

had been burning brightly in my mind since I was more or less out of a

high-chair.

My father

had been badly injured in a training exercise in the First World War and to him

poetry was a painkiller. “Poetry can stop you feeling ill,” he’d say simply.

had been badly injured in a training exercise in the First World War and to him

poetry was a painkiller. “Poetry can stop you feeling ill,” he’d say simply.

England

in the late forties and early fifties was a world without television; a world

where visits to the cinema were a rarity and where the radio was a cumbersome

mahogany box with a forbidding grille: unfriendly, dusty and predominantly

silent due to its aggregation of valves overheating whereupon the whole

contraption would black out with a sorry ‘phut!’. I associate childhood

radio with a distinctive smell of burning dust as much as with entertainment.

in the late forties and early fifties was a world without television; a world

where visits to the cinema were a rarity and where the radio was a cumbersome

mahogany box with a forbidding grille: unfriendly, dusty and predominantly

silent due to its aggregation of valves overheating whereupon the whole

contraption would black out with a sorry ‘phut!’. I associate childhood

radio with a distinctive smell of burning dust as much as with entertainment.

There was

a prevailing quiet if not gloom in those early post-war years. My father, born

in Queen Victoria’s reign, once persuaded me with dark whimsy that there was a

government institution called The Ministry of Silence which was capable of

meting out stern punishments to those who offended against its precepts. I half

believed him. Books, and particularly poems, were therefore the media of

choice, and an escape hatch.

a prevailing quiet if not gloom in those early post-war years. My father, born

in Queen Victoria’s reign, once persuaded me with dark whimsy that there was a

government institution called The Ministry of Silence which was capable of

meting out stern punishments to those who offended against its precepts. I half

believed him. Books, and particularly poems, were therefore the media of

choice, and an escape hatch.

|

| William Ernest Henley |

By

coincidence, my mother’s maiden name was Henley and it happened that William

Ernest Henley, the author of ‘Invictus’ was, in fact, a cousin at several

removes. Henley had come from Bristol and he’d had tuberculosis of the bone as

a child which resulted in one of his legs being amputated. He became a friend

of Robert Louis Stevenson and as such was thought to have been the inspiration

for Stevenson’s portrait of the one-legged pirate, Long John Silver.

coincidence, my mother’s maiden name was Henley and it happened that William

Ernest Henley, the author of ‘Invictus’ was, in fact, a cousin at several

removes. Henley had come from Bristol and he’d had tuberculosis of the bone as

a child which resulted in one of his legs being amputated. He became a friend

of Robert Louis Stevenson and as such was thought to have been the inspiration

for Stevenson’s portrait of the one-legged pirate, Long John Silver.

Judging

from a description of Henley by his stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, Stevenson’s

imaginative leap hadn’t been too hard to make:

from a description of Henley by his stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, Stevenson’s

imaginative leap hadn’t been too hard to make:

“… a

great, glowing, massive-shouldered fellow with a big red beard and a

crutch; jovial, astoundingly clever, and with a laugh that rolled like

music; he had an unimaginable fire and vitality; he swept one off one’s

feet”.

great, glowing, massive-shouldered fellow with a big red beard and a

crutch; jovial, astoundingly clever, and with a laugh that rolled like

music; he had an unimaginable fire and vitality; he swept one off one’s

feet”.

Stevenson

would later acknowledge the connection in a letter to Henley:

would later acknowledge the connection in a letter to Henley:

“I will

now make a confession: It was the sight of your maimed strength and

masterfulness that begot Long John Silver … the idea of the maimed man,

ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you.”

now make a confession: It was the sight of your maimed strength and

masterfulness that begot Long John Silver … the idea of the maimed man,

ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you.”

Striking

as Henley’s verses were it was Henley’s piratical connection that caught my

imagination, rather more than Henley himself or indeed the poem which found

such favour with my father.

as Henley’s verses were it was Henley’s piratical connection that caught my

imagination, rather more than Henley himself or indeed the poem which found

such favour with my father.

Although

Henley’s paean to self-mastery was popular as a fireside morale-booster,

Henley’s part in bringing Long John Silver into existence (albeit through a

childhood illness rather than through actual piracy) weighed with me much more.

It was like a feather in the genetic cap from which I derived a quiet glow,

believing it to bestow outsider, if not outlaw, status.

Henley’s paean to self-mastery was popular as a fireside morale-booster,

Henley’s part in bringing Long John Silver into existence (albeit through a

childhood illness rather than through actual piracy) weighed with me much more.

It was like a feather in the genetic cap from which I derived a quiet glow,

believing it to bestow outsider, if not outlaw, status.

The

promised outing to see another poet – who also had what my father hinted was a

slightly outlaw-like reputation – took place on Saturday, 11th

August, 1951 in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Lecture Hall. It was part of a

Festival of Books that the Museum had been mounting in association with the

Festival of Britain.

promised outing to see another poet – who also had what my father hinted was a

slightly outlaw-like reputation – took place on Saturday, 11th

August, 1951 in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Lecture Hall. It was part of a

Festival of Books that the Museum had been mounting in association with the

Festival of Britain.

My father

and I found our way to the front of the audience and we sat down directly

beneath a small, plump man with curly auburn hair, a raffish bow-tie, loud

checkered tweeds and a shining face who stood patiently behind a wooden lectern

a few feet above us.

and I found our way to the front of the audience and we sat down directly

beneath a small, plump man with curly auburn hair, a raffish bow-tie, loud

checkered tweeds and a shining face who stood patiently behind a wooden lectern

a few feet above us.

I

remember that he seemed not to be able to hold himself still and he swayed

gently from side to side as if caught by a rough sea-breeze. I was almost

immediately below him. From my perspective, he was spasmodically hidden behind

a large pint glass of amber-colored liquid from where he would tantalizingly

slide in and out of view.

remember that he seemed not to be able to hold himself still and he swayed

gently from side to side as if caught by a rough sea-breeze. I was almost

immediately below him. From my perspective, he was spasmodically hidden behind

a large pint glass of amber-colored liquid from where he would tantalizingly

slide in and out of view.

This

human metronome, seemingly set to some slow internal beat, shuffled his

slightly soggy handwritten papers and then, after a brief introduction from the

Museum’s Curator, Dylan Thomas sprang to life.

human metronome, seemingly set to some slow internal beat, shuffled his

slightly soggy handwritten papers and then, after a brief introduction from the

Museum’s Curator, Dylan Thomas sprang to life.

He pitched

into a series of unstoppable recitations. His eyes bulged and his voice

resonated, boomingly and rhythmically with a series of florid arias spilling

out of his diminutive frame (A phenomenon which was accompanied by misty sprays

of saliva that I remember my father found hard to forgive.)

into a series of unstoppable recitations. His eyes bulged and his voice

resonated, boomingly and rhythmically with a series of florid arias spilling

out of his diminutive frame (A phenomenon which was accompanied by misty sprays

of saliva that I remember my father found hard to forgive.)

Dylan was

so possessed that I thought he might go off like a bomb with his fizzing and

surging. I’d not seen anyone drunk before and he was clearly drunk but he was

also a phenomenon, as drunk on language as on alcohol. He was caught up by

great muscular waves of language – anthemic, torrential and spell-binding

– whose meaning was lost on me but whose effect was hypnotic.

so possessed that I thought he might go off like a bomb with his fizzing and

surging. I’d not seen anyone drunk before and he was clearly drunk but he was

also a phenomenon, as drunk on language as on alcohol. He was caught up by

great muscular waves of language – anthemic, torrential and spell-binding

– whose meaning was lost on me but whose effect was hypnotic.

I’d been

to the Albert Hall once and I’d heard that building’s enormous organ with its

golden pipes that so dominate the Hall’s interior and I remember that I’d

compared Dylan Thomas’ voice to the sound of it when my father asked me

afterwards what I ‘d thought of Dylan’s performance.

to the Albert Hall once and I’d heard that building’s enormous organ with its

golden pipes that so dominate the Hall’s interior and I remember that I’d

compared Dylan Thomas’ voice to the sound of it when my father asked me

afterwards what I ‘d thought of Dylan’s performance.

I can

only recall one line from the reading with any certainty, “I see the boys of

summer in their ruin…” I particularly remembered it because my father would

repeat it over the years. Whenever it looked to him as if I was going off the

rails, he’d trot out this line, to my chagrin as he’d quite spoil it by giving

it a stern, judgmental almost taunting edge.

only recall one line from the reading with any certainty, “I see the boys of

summer in their ruin…” I particularly remembered it because my father would

repeat it over the years. Whenever it looked to him as if I was going off the

rails, he’d trot out this line, to my chagrin as he’d quite spoil it by giving

it a stern, judgmental almost taunting edge.

After

Thomas’ reading was over my father and I filed out of the auditorium and my

father brought me home, announcing to my mother, in a matter-of-fact fashion,

that “The boy was hypnotized” which was true. I still cherish a vivid, dreamy

sense of having been entranced. Rhapsodically entranced.

Thomas’ reading was over my father and I filed out of the auditorium and my

father brought me home, announcing to my mother, in a matter-of-fact fashion,

that “The boy was hypnotized” which was true. I still cherish a vivid, dreamy

sense of having been entranced. Rhapsodically entranced.

Evidently

I’d not kicked my feet in the air out of boredom once and so, to my father’s

relief, I’d needed no chastening, but instead I seem to have surrendered myself

to that great organ of a voice which Dylan possessed and I’d remained entirely

still throughout. There’d been no microphone in the venue. It was just

Dylan’s voice from a few feet away.

I’d not kicked my feet in the air out of boredom once and so, to my father’s

relief, I’d needed no chastening, but instead I seem to have surrendered myself

to that great organ of a voice which Dylan possessed and I’d remained entirely

still throughout. There’d been no microphone in the venue. It was just

Dylan’s voice from a few feet away.

It was

not a wholly Welsh voice. It was certainly Welsh in its impassioned soaring,

but it was a voice that had by now mutated into a highly stylized theatrical

projection housed within what’s called ‘Received Pronunciation’, or more

frequently ‘BBC English’.

not a wholly Welsh voice. It was certainly Welsh in its impassioned soaring,

but it was a voice that had by now mutated into a highly stylized theatrical

projection housed within what’s called ‘Received Pronunciation’, or more

frequently ‘BBC English’.

Thomas

was certainly aware of his slightly managed magniloquence and he was happy to

milk it to maximum effect, whilst at the same time poking fun at himself:

deprecating what was something of an assumed, actor-ish persona with the

sobriquet, “Lord Cut-Glass.”

was certainly aware of his slightly managed magniloquence and he was happy to

milk it to maximum effect, whilst at the same time poking fun at himself:

deprecating what was something of an assumed, actor-ish persona with the

sobriquet, “Lord Cut-Glass.”

My father

also apparently told my mother (my mother would later tell me) that although I

was “hypnotized” I couldn’t possibly have understood a word of what Dylan

Thomas had been “on about” since my father hadn’t understood much, if indeed

anything at all. He’d say gruffly, “none of it meant much to me.”

also apparently told my mother (my mother would later tell me) that although I

was “hypnotized” I couldn’t possibly have understood a word of what Dylan

Thomas had been “on about” since my father hadn’t understood much, if indeed

anything at all. He’d say gruffly, “none of it meant much to me.”

He was

aware that Dylan was in some way “modern” but I think that he may also have had

an uneasy feeling that his fellow Welshman was letting the side down by being,

as he clearly thought, quite so wilfully obscure. However my father’s

strictures were of no avail, the damage was done, and a potent seed was

planted.

aware that Dylan was in some way “modern” but I think that he may also have had

an uneasy feeling that his fellow Welshman was letting the side down by being,

as he clearly thought, quite so wilfully obscure. However my father’s

strictures were of no avail, the damage was done, and a potent seed was

planted.

Although

my father’s feelings about Thomas’ poetry were dismissive, it turned out that

he, in fact, possessed a copy of Thomas’ ‘Eighteen Poems’, a slim volume

published when Thomas was just 20, and after the reading my father, an avid

book-collector, gave it to me, taking some pride in his foresight, and I was

grateful as I could then start to familiarize myself with some of the poems

that I’d just heard Dylan perform.

my father’s feelings about Thomas’ poetry were dismissive, it turned out that

he, in fact, possessed a copy of Thomas’ ‘Eighteen Poems’, a slim volume

published when Thomas was just 20, and after the reading my father, an avid

book-collector, gave it to me, taking some pride in his foresight, and I was

grateful as I could then start to familiarize myself with some of the poems

that I’d just heard Dylan perform.

“Should

lanterns shine this holy face caught in an octagon of unaccustomed light would

wither up…” was one of them. I didn’t pretend to understand it either, but

nonetheless I persuaded myself that, unlike my father, I knew what the lines

meant since they carried the sound of sense and also because, when I

read them aloud, I was able to relive that trance-like state in the Victoria

and Albert Museum.

lanterns shine this holy face caught in an octagon of unaccustomed light would

wither up…” was one of them. I didn’t pretend to understand it either, but

nonetheless I persuaded myself that, unlike my father, I knew what the lines

meant since they carried the sound of sense and also because, when I

read them aloud, I was able to relive that trance-like state in the Victoria

and Albert Museum.

The

reading in the Museum had been an entirely new kind of pleasure, different from

anything I’d previously experienced. It was even quite close to what would

later be described as ‘psychedelic’. Words, thanks to Dylan, were now things,

things that could affect your metabolism. “Love the words,” Dylan

was to say to the cast of his play ‘Under Milk Wood’ when it was performed in

New York at the end of the decade: “Love the words” and, when I

heard them as a child from Dylan Thomas himself, I certainly had.

reading in the Museum had been an entirely new kind of pleasure, different from

anything I’d previously experienced. It was even quite close to what would

later be described as ‘psychedelic’. Words, thanks to Dylan, were now things,

things that could affect your metabolism. “Love the words,” Dylan

was to say to the cast of his play ‘Under Milk Wood’ when it was performed in

New York at the end of the decade: “Love the words” and, when I

heard them as a child from Dylan Thomas himself, I certainly had.

Years

later I went to a lecture that Robert Graves gave at the Taylorian Institute in

Oxford, and afterwards (Thomas now having become an enduring affection) I asked

Graves what he thought of Thomas’ work. He looked down his nose – a large

nose unevenly broken while playing Rugby into the impressive shape of a Roman

Emperor’s nose – and he said just one word: “The hwyl.”

later I went to a lecture that Robert Graves gave at the Taylorian Institute in

Oxford, and afterwards (Thomas now having become an enduring affection) I asked

Graves what he thought of Thomas’ work. He looked down his nose – a large

nose unevenly broken while playing Rugby into the impressive shape of a Roman

Emperor’s nose – and he said just one word: “The hwyl.”

In that

almost untranslatable, portmanteau Welsh word, Graves had uttered the most

useful clue to Dylan: the hwyl, a word whose meaning can range from

spirit possession, to health, and also, very simply, to just ‘hello’,

almost untranslatable, portmanteau Welsh word, Graves had uttered the most

useful clue to Dylan: the hwyl, a word whose meaning can range from

spirit possession, to health, and also, very simply, to just ‘hello’,

As

Dylan’s Swansea friend, Leon Atkin, would explain to me years later, the

hwyl (pronounced ‘Hoil’) was that ecstatic peroration which occurs at the

end of an old-fashioned Welsh sermon in order to stoke up an surge of

spirituality in dissenter congregations and Thomas, with his juicy, neo-pagan

psalms celebrating nature combined with a subversive politics, had the hwyl

in spades and he used it to great effect.

Dylan’s Swansea friend, Leon Atkin, would explain to me years later, the

hwyl (pronounced ‘Hoil’) was that ecstatic peroration which occurs at the

end of an old-fashioned Welsh sermon in order to stoke up an surge of

spirituality in dissenter congregations and Thomas, with his juicy, neo-pagan

psalms celebrating nature combined with a subversive politics, had the hwyl

in spades and he used it to great effect.

When I’d

grown up my mother would often tell people about the Victoria and Albert visit

as if this was the place where I’d contracted “the bug” – the bug which, by her

lights, had taught me to behave oddly and to be determined to earn no money and

thus be off the grid.

grown up my mother would often tell people about the Victoria and Albert visit

as if this was the place where I’d contracted “the bug” – the bug which, by her

lights, had taught me to behave oddly and to be determined to earn no money and

thus be off the grid.

By her

lights the germ of what she regarded as a kind of euphoric fecklessness had

evidently been contracted in the Victoria and Albert Museum all those years ago

and she used it to explain to herself why I wouldn’t be going in for the church

as a priest as she’d not so secretly desired. She certainly never countenanced

the idea that poetry could be another kind of priestly vocation and, being

devout and quite strait-laced, viewed such a notion as being close to

blasphemy.

lights the germ of what she regarded as a kind of euphoric fecklessness had

evidently been contracted in the Victoria and Albert Museum all those years ago

and she used it to explain to herself why I wouldn’t be going in for the church

as a priest as she’d not so secretly desired. She certainly never countenanced

the idea that poetry could be another kind of priestly vocation and, being

devout and quite strait-laced, viewed such a notion as being close to

blasphemy.

Major

events were few and far between in London in the late forties and fifties. The

city was a bleak wasteland. Every other block in the street in which we lived

was a bombsite, and the whole city was to remain a malingering bombsite for

years during my childhood whilst a bankrupt England paid off its war debt to

its wartime benefactor and now demanding creditor, America.

events were few and far between in London in the late forties and fifties. The

city was a bleak wasteland. Every other block in the street in which we lived

was a bombsite, and the whole city was to remain a malingering bombsite for

years during my childhood whilst a bankrupt England paid off its war debt to

its wartime benefactor and now demanding creditor, America.

Highlights

were rare. There was the soaring and futuristic Skylon at the Festival of

Britain; there was the Big Dipper at Battersea Fun Fair; the Model Railway

Exhibition at the Horticultural Hall; Maskelyne and Devant’s Magic Show at the

Scala Theatre in Charlotte Street and the Crazy Gang at the Victoria Palace.

were rare. There was the soaring and futuristic Skylon at the Festival of

Britain; there was the Big Dipper at Battersea Fun Fair; the Model Railway

Exhibition at the Horticultural Hall; Maskelyne and Devant’s Magic Show at the

Scala Theatre in Charlotte Street and the Crazy Gang at the Victoria Palace.

There

must have been other high points in that flattened and flat decade, the

nineteen fifties, but those are the only ones that I remember and so hearing

Dylan Thomas’ reading was a peak event, if only because my father would go out

of his way to make anything remotely cultural seem special.

must have been other high points in that flattened and flat decade, the

nineteen fifties, but those are the only ones that I remember and so hearing

Dylan Thomas’ reading was a peak event, if only because my father would go out

of his way to make anything remotely cultural seem special.

My father

was Welsh and Thomas was Welsh and, without his ever saying much about it, my

father must, at some point, have infected me with some native pride. Neither

he, nor indeed Thomas, spoke any Welsh although both their fathers had. My

grandfather Joe, who made stained glass windows in Covent Garden, spoke it and,

as my father was fond of boasting, Welsh was Britain’s first language,

although, somewhat hypocritically, he’d never bothered to give the language the

time of day by learning much more than a syllable or two, although I do

remember his teaching me what he claimed had been the Druids’ motto, Y gywr

yn erbyn y bwd – the truth against the world. He’d remind me of it if I was

being less than direct, and he’d accompany his delivery of this ancient edict

with a forbidding stare.

was Welsh and Thomas was Welsh and, without his ever saying much about it, my

father must, at some point, have infected me with some native pride. Neither

he, nor indeed Thomas, spoke any Welsh although both their fathers had. My

grandfather Joe, who made stained glass windows in Covent Garden, spoke it and,

as my father was fond of boasting, Welsh was Britain’s first language,

although, somewhat hypocritically, he’d never bothered to give the language the

time of day by learning much more than a syllable or two, although I do

remember his teaching me what he claimed had been the Druids’ motto, Y gywr

yn erbyn y bwd – the truth against the world. He’d remind me of it if I was

being less than direct, and he’d accompany his delivery of this ancient edict

with a forbidding stare.

Although

he’d made the forthcoming occasion seem special my father could have had no

idea quite how seminal the reading was to prove. As a result of being bitten by

this “bug”, as my mother put it, I was shortly to collect all the recordings of

Dylan Thomas that I could lay my hands on. Recordings of Dylan’s reading tours,

had been made by two stalwart American girls lugging primitive and, in those

days, punitively heavy equipment in Dylan’s footsteps.

he’d made the forthcoming occasion seem special my father could have had no

idea quite how seminal the reading was to prove. As a result of being bitten by

this “bug”, as my mother put it, I was shortly to collect all the recordings of

Dylan Thomas that I could lay my hands on. Recordings of Dylan’s reading tours,

had been made by two stalwart American girls lugging primitive and, in those

days, punitively heavy equipment in Dylan’s footsteps.

The

recordings included not only Thomas reading his own work but also poems by

other authors whom Dylan had liked and admired and had chosen to read. There

were poems by Auden, Yeats and D. H. Lawrence; by Thomas Hardy, and Walter De

La Mare. Dylan read “The Three Bushes” by Yeats, “Whales Weep Not” by Lawrence,

“Broken Appointment” by Hardy, “At the Keyhole” and the comically touching,

‘The Bards’ by De La Mare about Wordsworth and Coleridge in old age.

recordings included not only Thomas reading his own work but also poems by

other authors whom Dylan had liked and admired and had chosen to read. There

were poems by Auden, Yeats and D. H. Lawrence; by Thomas Hardy, and Walter De

La Mare. Dylan read “The Three Bushes” by Yeats, “Whales Weep Not” by Lawrence,

“Broken Appointment” by Hardy, “At the Keyhole” and the comically touching,

‘The Bards’ by De La Mare about Wordsworth and Coleridge in old age.

Through

the miracle of this pioneering piece of recorded speech published by Caedmon

(named after Caedmon the seventh century monk who dreamt his poems and woke up

singing them) it seemed that all of these poetic spirits had been made

immortal. It was as if the recordings were able to punch holes in time.

the miracle of this pioneering piece of recorded speech published by Caedmon

(named after Caedmon the seventh century monk who dreamt his poems and woke up

singing them) it seemed that all of these poetic spirits had been made

immortal. It was as if the recordings were able to punch holes in time.

I was to

leave school under a slight cloud. I’d entered into a brief correspondence with

the junior branch of the Communist party on King Street, in Covent Garden –

more out of a mischievous curiosity than from any strong political commitment.

Communism during the Cold War was taboo. My schoolboy correspondence was

discovered through my mail having been opened and since in the late fifties

anti-Soviet propaganda and spy paranoia was all-pervasive and since Communist

Russia had succeeded Nazi Germany as “the enemy” it was thought ill-considered.

leave school under a slight cloud. I’d entered into a brief correspondence with

the junior branch of the Communist party on King Street, in Covent Garden –

more out of a mischievous curiosity than from any strong political commitment.

Communism during the Cold War was taboo. My schoolboy correspondence was

discovered through my mail having been opened and since in the late fifties

anti-Soviet propaganda and spy paranoia was all-pervasive and since Communist

Russia had succeeded Nazi Germany as “the enemy” it was thought ill-considered.

Out of

the blue, my father received a letter from the school authorities which

mentioned my Communist associations with disapproval and they suggested that I

was, in the housemaster’s words, “no longer benefiting from the elitist

education which the school prided itself on being able to offer”. Clearly, the

housemaster said, no purpose was to be served by my remaining there any

further.

the blue, my father received a letter from the school authorities which

mentioned my Communist associations with disapproval and they suggested that I

was, in the housemaster’s words, “no longer benefiting from the elitist

education which the school prided itself on being able to offer”. Clearly, the

housemaster said, no purpose was to be served by my remaining there any

further.

My father

was incandescent, and it was his cue for Dylan’s line about “the boys in summer

in their ruin” to be invoked, but I was happy to leave both school and home

and, after a brief spell in a Franciscan monastery in Dorset helping to look

after their bees, I took to the road.

was incandescent, and it was his cue for Dylan’s line about “the boys in summer

in their ruin” to be invoked, but I was happy to leave both school and home

and, after a brief spell in a Franciscan monastery in Dorset helping to look

after their bees, I took to the road.

I’d read

the poet W.H. Davies’ ‘Autobiography of a Super-Tramp’ and I fondly imagined,

along with this Welsh proto-Beat, (“What is life if full of care/There is no

time to stop and stare”) that, were you resourceful enough, you could survive

on little to nothing. For no reason other than the germinative Victoria and

Albert Museum reading, I’d set my sights on Swansea, thinking and hoping that

this might be somewhere to find a different kind of spiritual sustenance, given

the poet whom Swansea had spawned.

the poet W.H. Davies’ ‘Autobiography of a Super-Tramp’ and I fondly imagined,

along with this Welsh proto-Beat, (“What is life if full of care/There is no

time to stop and stare”) that, were you resourceful enough, you could survive

on little to nothing. For no reason other than the germinative Victoria and

Albert Museum reading, I’d set my sights on Swansea, thinking and hoping that

this might be somewhere to find a different kind of spiritual sustenance, given

the poet whom Swansea had spawned.

I had

another book that I took with me: ‘The Campers and Trampers Weekend Book’ by

Showell Styles which extolled the virtue of “just living for the next bend in

the road”. It was full of handy survival tips although I’d soon find that

living for the ‘next bend in the highways and by-ways’ wasn’t as romantic as

I’d been imagining in my teenage dreams.

another book that I took with me: ‘The Campers and Trampers Weekend Book’ by

Showell Styles which extolled the virtue of “just living for the next bend in

the road”. It was full of handy survival tips although I’d soon find that

living for the ‘next bend in the highways and by-ways’ wasn’t as romantic as

I’d been imagining in my teenage dreams.

I naively

thought that I’d be falling into a ready-made camaraderie of gentlemen of the

road, a collection of gypsy encampments even, straight out of George Borrow,

and that perhaps there’d be the ‘spikes’ that had housed the unemployed of

Orwell’s ‘Down and Out in Paris and London’ positioned at convenient places

along the route. But this was a fantasy; such places no longer existed

although there were a couple of Salvation Army Hostels en route and I’d

set off from a Rowton House at the Elephant and Castle where I’d holed up for a

bit.

thought that I’d be falling into a ready-made camaraderie of gentlemen of the

road, a collection of gypsy encampments even, straight out of George Borrow,

and that perhaps there’d be the ‘spikes’ that had housed the unemployed of

Orwell’s ‘Down and Out in Paris and London’ positioned at convenient places

along the route. But this was a fantasy; such places no longer existed

although there were a couple of Salvation Army Hostels en route and I’d

set off from a Rowton House at the Elephant and Castle where I’d holed up for a

bit.

I made it

to Swansea mainly by walking and hitching, and, after a tip from an elderly

vagrant in the centre of town, I found my way to a Crypt below St Paul’s Church

in St Helen’s Road, Swansea, where, just as this providential gentleman of the

road had indicated, “the Reverend Leon Atkin will see you right.”

to Swansea mainly by walking and hitching, and, after a tip from an elderly

vagrant in the centre of town, I found my way to a Crypt below St Paul’s Church

in St Helen’s Road, Swansea, where, just as this providential gentleman of the

road had indicated, “the Reverend Leon Atkin will see you right.”

The Crypt

turned out to contain an assortment of refugees: there was a man who’d kept a

collection of telescopes in a tent on Mumbles Bay but who had, inexplicably,

“to bring them in for the winter.” His huge brass tubes were accordingly piled

up in leather boxes beneath a Church trestle table upon which Leon Atkin would daily

place a great spread of food for the Crypt’s transient residents.

turned out to contain an assortment of refugees: there was a man who’d kept a

collection of telescopes in a tent on Mumbles Bay but who had, inexplicably,

“to bring them in for the winter.” His huge brass tubes were accordingly piled

up in leather boxes beneath a Church trestle table upon which Leon Atkin would daily

place a great spread of food for the Crypt’s transient residents.

In

addition to this roving astronomer, there was a pair of petty criminals who

were apparently wanted by the police for some nefarious dealings “in the

smoke”, i.e. up in London. There was a prickly bare-knuckle boxer whom

you had to be careful to skirt around especially when he was in his cups.

Others drifted in and out. There were unemployed casual laborers and those

simply unable to fend for themselves – people the French call les marginales.

addition to this roving astronomer, there was a pair of petty criminals who

were apparently wanted by the police for some nefarious dealings “in the

smoke”, i.e. up in London. There was a prickly bare-knuckle boxer whom

you had to be careful to skirt around especially when he was in his cups.

Others drifted in and out. There were unemployed casual laborers and those

simply unable to fend for themselves – people the French call les marginales.

As far as

I could gather, thanks to the benignly anarchic sense of community established

by Leon, you could come and go as you pleased. When this white-maned and burly

figure appeared in the Crypt’s combined dormitory and living space, as he did daily,

he’d greet everyone warmly and make sure that they had enough to eat and were

supplied with proper bedding from the vestry where there were about forty camp

beds. Each morning Leon would seize hold of a huge industrial-sized coal

scuttle and fill it up from the bunker outside, then he’d ensure that the stove

was generously topped up and that the radiators in the Crypt were in good

working order, slapping them approvingly if they were.

I could gather, thanks to the benignly anarchic sense of community established

by Leon, you could come and go as you pleased. When this white-maned and burly

figure appeared in the Crypt’s combined dormitory and living space, as he did daily,

he’d greet everyone warmly and make sure that they had enough to eat and were

supplied with proper bedding from the vestry where there were about forty camp

beds. Each morning Leon would seize hold of a huge industrial-sized coal

scuttle and fill it up from the bunker outside, then he’d ensure that the stove

was generously topped up and that the radiators in the Crypt were in good

working order, slapping them approvingly if they were.

All were

invited, in a casual fashion, to attend Leon’s church upstairs, in the main

body of the building, but no one was ever expected to. Board and lodging was

free and came with no strings attached. It was the closest thing to

unconditional love that I’d ever experienced and it was always understated.

Leon gave off a kind of quiet, selfless radiance. There was no subtext, just a

feeling of benign transcendence; grace even.

invited, in a casual fashion, to attend Leon’s church upstairs, in the main

body of the building, but no one was ever expected to. Board and lodging was

free and came with no strings attached. It was the closest thing to

unconditional love that I’d ever experienced and it was always understated.

Leon gave off a kind of quiet, selfless radiance. There was no subtext, just a

feeling of benign transcendence; grace even.

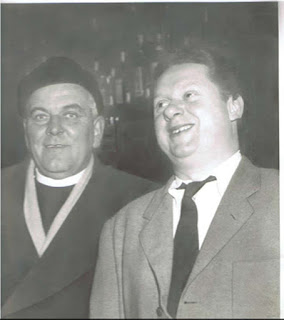

When I

got to know him and when I told him that I’d seen Dylan Thomas reading a few

years before and that I’d come to Swansea hoping to find people who knew him,

Leon’s smile broadened and he told me that he’d known Dylan well, “since he was

a lad”, and he missed him sorely, although, “The only time I saw Dylan in a

church was when his coffin was taken in for the funeral service”.

got to know him and when I told him that I’d seen Dylan Thomas reading a few

years before and that I’d come to Swansea hoping to find people who knew him,

Leon’s smile broadened and he told me that he’d known Dylan well, “since he was

a lad”, and he missed him sorely, although, “The only time I saw Dylan in a

church was when his coffin was taken in for the funeral service”.

“Like to

hear a story about him?” Leon enquired. I nodded enthusiastically, “You

ever hear of the Blackshirts?” I said that I had. ”Well, they tried to hold a

rally here, in the Plaza Cinema in ’34. Dylan and I went to it, along

with Dylan’s communist friend Bert Trick, and did we give them what for? We

did. We did,” He twinkled in anticipation of reliving the story.

hear a story about him?” Leon enquired. I nodded enthusiastically, “You

ever hear of the Blackshirts?” I said that I had. ”Well, they tried to hold a

rally here, in the Plaza Cinema in ’34. Dylan and I went to it, along

with Dylan’s communist friend Bert Trick, and did we give them what for? We

did. We did,” He twinkled in anticipation of reliving the story.

“The

British Union of Fascists they called themselves and the leader of the

Blackshirts was an Englishman called Sir Oswald Mosley. He was a fierce man for

attacking the Jews was this Mosley – Sir Oswald if you please – and all

of Swansea knew of him in advance and of his horrid foulness, you see?” I

nodded.

British Union of Fascists they called themselves and the leader of the

Blackshirts was an Englishman called Sir Oswald Mosley. He was a fierce man for

attacking the Jews was this Mosley – Sir Oswald if you please – and all

of Swansea knew of him in advance and of his horrid foulness, you see?” I

nodded.

“Now” –

Leon leant forward conspiratorially – “their modus operandi was to

invite questions from the audience which were to be written down and then

they’d pass them up to this Mosley creature for him to answer.

Leon leant forward conspiratorially – “their modus operandi was to

invite questions from the audience which were to be written down and then

they’d pass them up to this Mosley creature for him to answer.

“I wrote

down, “I work for a Jew. Do you think I should change my employer?”

down, “I work for a Jew. Do you think I should change my employer?”

“Well, at

this Mosley curled his thin lip and expressed disgust that anyone should work

for a Jew, and then he said that “surely the questioner would be certain to

find someone more reliable to work for, amongst Swansea’s Gentiles?” and then

this Mosley looked about him and he said to the audience, “Now, who asked this?

My advice to you is that you should find a new employer.”

this Mosley curled his thin lip and expressed disgust that anyone should work

for a Jew, and then he said that “surely the questioner would be certain to

find someone more reliable to work for, amongst Swansea’s Gentiles?” and then

this Mosley looked about him and he said to the audience, “Now, who asked this?

My advice to you is that you should find a new employer.”

“They’d

always ask this, see? ‘Who asked this question?’ and if was a question that

they didn’t like then their thugs and their bully boys would escort the

questioner outside and they’d more than likely duff him up, but this time, of

course, it was their undoing because I stood up and, of course, when I stood up

then I exposed my clerical collar.”

always ask this, see? ‘Who asked this question?’ and if was a question that

they didn’t like then their thugs and their bully boys would escort the

questioner outside and they’d more than likely duff him up, but this time, of

course, it was their undoing because I stood up and, of course, when I stood up

then I exposed my clerical collar.”

At this

Leon chuckled, “Thus revealing who it was that I worked for. The penny dropped.

Quite loudly. The audience got it. ‘That’s Reverend Leon!’ they cried.

All hell broke loose. The Plaza held three thousand people. Three thousand

people up in arms!

Leon chuckled, “Thus revealing who it was that I worked for. The penny dropped.

Quite loudly. The audience got it. ‘That’s Reverend Leon!’ they cried.

All hell broke loose. The Plaza held three thousand people. Three thousand

people up in arms!

“Well,

they had to squirrel Mosley out through the back door, didn’t they? He was

ranting and squawking “Blasphemy! Blasphemy!” and then the audience weighed in.

They attacked the Blackshirts. Dylan and Bert and I, we were all pretty handy

with our fists.” Leon looked up at me, and then added, slightly apologetically,

“To do good, you know, in this life you must sometimes use your fists. Bit

shocking but there we are. ‘What weapon has the lion but himself?’ Know that

line? It’s John Keats.

they had to squirrel Mosley out through the back door, didn’t they? He was

ranting and squawking “Blasphemy! Blasphemy!” and then the audience weighed in.

They attacked the Blackshirts. Dylan and Bert and I, we were all pretty handy

with our fists.” Leon looked up at me, and then added, slightly apologetically,

“To do good, you know, in this life you must sometimes use your fists. Bit

shocking but there we are. ‘What weapon has the lion but himself?’ Know that

line? It’s John Keats.

“Oh yes,”

he continued, “Dylan was spot on about the Blackshirts. He’d talk about their

‘curdled patriotism’ – that was his phrase – and then he’d describe that

scrawny old demagogue, Mosley, as suffering ‘From an elephantiasis of the

soul’. Quite a juxtaposition that, eh?” and Leon laughed in a great rumbling

peal as he recollected “the great Plaza Cinema rout! Yes. Just down the

road from here, you know. It’s there still. It survived the bombing, but Mosley

hasn’t though. He’s completely discredited now.”

he continued, “Dylan was spot on about the Blackshirts. He’d talk about their

‘curdled patriotism’ – that was his phrase – and then he’d describe that

scrawny old demagogue, Mosley, as suffering ‘From an elephantiasis of the

soul’. Quite a juxtaposition that, eh?” and Leon laughed in a great rumbling

peal as he recollected “the great Plaza Cinema rout! Yes. Just down the

road from here, you know. It’s there still. It survived the bombing, but Mosley

hasn’t though. He’s completely discredited now.”

Leon

Atkin described himself as a “minister of the Social Gospel.” He’d started the

refuge in the nineteen thirties, and in the bitter winter of 1947 his Crypt

became a friendly oasis for dozens of men who might otherwise have died. On

every Friday evening for decades Leon would visit every public house in Swansea

to collect money for the hostel and to enable Swansea’s children to enjoy a Guy

Fawkes’ night with a stupendous firework display on the beach, and they’d also

be taken by him in three huge parties to the circus.

Atkin described himself as a “minister of the Social Gospel.” He’d started the

refuge in the nineteen thirties, and in the bitter winter of 1947 his Crypt

became a friendly oasis for dozens of men who might otherwise have died. On

every Friday evening for decades Leon would visit every public house in Swansea

to collect money for the hostel and to enable Swansea’s children to enjoy a Guy

Fawkes’ night with a stupendous firework display on the beach, and they’d also

be taken by him in three huge parties to the circus.

Disillusioned

with political parties and regarding them as being inept in their ability to

deal with the underprivileged, Leon was to stand as a ‘People’s Party’

candidate and he heroically polled over two thousand votes.

with political parties and regarding them as being inept in their ability to

deal with the underprivileged, Leon was to stand as a ‘People’s Party’

candidate and he heroically polled over two thousand votes.

When

Dylan was alive, Dylan would always make a point of seeing Leon, referring to

him as “my priest”, and when Leon was asked by David Thomas, the local Swansea

historian, for his memories of Dylan, it was always Dylan’s spiritual virtues

that were in the forefront of Leon’s recollection:

Dylan was alive, Dylan would always make a point of seeing Leon, referring to

him as “my priest”, and when Leon was asked by David Thomas, the local Swansea

historian, for his memories of Dylan, it was always Dylan’s spiritual virtues

that were in the forefront of Leon’s recollection:

“He

[Dylan Thomas] lived, I suppose, more on faith than most parsons ever have

tried to do. And no one could ever accuse him of daring to submit his talent to

commercial interest. In fact, there were times when he looked like a tramp, and

I suppose he didn’t eat much more than a tramp. He always struck me as a man

whose soul was so much alive that he suffered. He suffered a lot, I think. But

every action he seemed to make was, according to my unorthodox view, a

religious action. It was an attempt to evaluate and appreciate and express

beauty and something that was lovely… He was a perfectionist… poor old Dylan,

he did just explode… you could almost say that he died in childbirth.”

[Dylan Thomas] lived, I suppose, more on faith than most parsons ever have

tried to do. And no one could ever accuse him of daring to submit his talent to

commercial interest. In fact, there were times when he looked like a tramp, and

I suppose he didn’t eat much more than a tramp. He always struck me as a man

whose soul was so much alive that he suffered. He suffered a lot, I think. But

every action he seemed to make was, according to my unorthodox view, a

religious action. It was an attempt to evaluate and appreciate and express

beauty and something that was lovely… He was a perfectionist… poor old Dylan,

he did just explode… you could almost say that he died in childbirth.”

Leon had

much more in common with the early, and resolutely pacifist, Christian church

rather than with the established church and, despite their both being quick

with their fists, he and Dylan were in fact staunch pacifists. Dylan was not

averse to firing off letters to the Swansea and West Wales Guardian in

which he railed against “the obscene hypocrisy of those war-mongers who

venerate Christ’s name and void their contagious rheum upon the first principle

of his Gospel.”

much more in common with the early, and resolutely pacifist, Christian church

rather than with the established church and, despite their both being quick

with their fists, he and Dylan were in fact staunch pacifists. Dylan was not

averse to firing off letters to the Swansea and West Wales Guardian in

which he railed against “the obscene hypocrisy of those war-mongers who

venerate Christ’s name and void their contagious rheum upon the first principle

of his Gospel.”

Dylan’s

radicalism is overlooked but Caitlin, his wife, once observed that the sight of

a uniform made him “physically sick” and in the same year that Leon, Dylan and

Bert Trick made Mosley’s Blackshirts a laughing stock and caused the Blackshirt

fascists to be banned from holding meetings in Neath, Llanelli, and Cardiff as

well as in Swansea, Dylan was writing in ‘New Verse’:

radicalism is overlooked but Caitlin, his wife, once observed that the sight of

a uniform made him “physically sick” and in the same year that Leon, Dylan and

Bert Trick made Mosley’s Blackshirts a laughing stock and caused the Blackshirt

fascists to be banned from holding meetings in Neath, Llanelli, and Cardiff as

well as in Swansea, Dylan was writing in ‘New Verse’:

“I take

my stand with any revolutionary body that asserts it to be the right of all men

to share, equally and impartially, every production of man from man and from

the sources of production at man’s disposal, for only through such an

essentially revolutionary body can there be the possibility of a communal art.”

my stand with any revolutionary body that asserts it to be the right of all men

to share, equally and impartially, every production of man from man and from

the sources of production at man’s disposal, for only through such an

essentially revolutionary body can there be the possibility of a communal art.”

The two

film scripts Dylan produced, though never filmed, also reveal his radical

concerns: The Doctor and the Devils was based on the adventures of the

body-snatchers, Burke and Hare, and showed how there is one law for the poor

and another for the rich; and Rebecca’s Daughters, based on the

toll-gate riots in Wales in 1843, exposed governments only bringing in reforms

when they were fearful of revolution.

film scripts Dylan produced, though never filmed, also reveal his radical

concerns: The Doctor and the Devils was based on the adventures of the

body-snatchers, Burke and Hare, and showed how there is one law for the poor

and another for the rich; and Rebecca’s Daughters, based on the

toll-gate riots in Wales in 1843, exposed governments only bringing in reforms

when they were fearful of revolution.

At the

time Dylan wrote his revolutionary manifesto for ‘New Verse’ a quarter of the

population of Swansea was out of work. In January 1934 Dylan wrote to his

friend Trevor Tregaskis Hughes, a short story writer from Swansea who worked

for British Rail at Euston Station, that “society to adjust itself has to break

itself; society… has grown up rotten with its capitalist child, and only revolutionary

socialism can clean it up”. He concluded, “Capitalism is a system made for a

time of scarcity.”

time Dylan wrote his revolutionary manifesto for ‘New Verse’ a quarter of the

population of Swansea was out of work. In January 1934 Dylan wrote to his

friend Trevor Tregaskis Hughes, a short story writer from Swansea who worked

for British Rail at Euston Station, that “society to adjust itself has to break

itself; society… has grown up rotten with its capitalist child, and only revolutionary

socialism can clean it up”. He concluded, “Capitalism is a system made for a

time of scarcity.”

In

November 1933 when Dylan was just 19, he was writing to Pamela Hansford Johnson

of “an outgrown and decaying system” in which “light is being turned into

darkness by the capitalists and industrialists… There is only one thing you and

I, who are of this generation, must look forward to, must work for and pray for

and, because, as we fondly hope, we are poets and voicers not only of our

personal selves but of our social selves, we must pray for it all the more

vehemently. It is the Revolution.”

November 1933 when Dylan was just 19, he was writing to Pamela Hansford Johnson

of “an outgrown and decaying system” in which “light is being turned into

darkness by the capitalists and industrialists… There is only one thing you and

I, who are of this generation, must look forward to, must work for and pray for

and, because, as we fondly hope, we are poets and voicers not only of our

personal selves but of our social selves, we must pray for it all the more

vehemently. It is the Revolution.”

Dylan

promises her that, when he’s outlined the political facts to her in greater

detail, she’ll want to “don your scarlet tie…” as he puts it, and then he adds,

“The precious seeds of revolution must not be wasted”.

promises her that, when he’s outlined the political facts to her in greater

detail, she’ll want to “don your scarlet tie…” as he puts it, and then he adds,

“The precious seeds of revolution must not be wasted”.

Dylan

would later extol what he came to call ‘Functional Anarchy’ (and indeed his

great friend Vernon Watkins said of him, “None has ever worn more brilliantly

the mask of anarchy” and his revolutionary ideals were influencing his

poetic output.

would later extol what he came to call ‘Functional Anarchy’ (and indeed his

great friend Vernon Watkins said of him, “None has ever worn more brilliantly

the mask of anarchy” and his revolutionary ideals were influencing his

poetic output.

“Remember

the procession of the old-young men,” Dylan Thomas would write of his pressing

social concerns and he would choose to write of them in what was, for him, an

unusually plain and accessible style:

the procession of the old-young men,” Dylan Thomas would write of his pressing

social concerns and he would choose to write of them in what was, for him, an

unusually plain and accessible style:

“From

dole queue to corner and back again,

From the

pinched, packed streets to the peak of slag

In the

bite of the winters with shovel and bag,

With a

drooping fag [cigarette] and a turned up collar,

Stamping

for the cold at the ill lit corner

Dragging

through the squalor with their hearts like lead

Staring

at the hunger and the shut pit-head

Nothing

in their pockets, nothing home to eat.

Lagging

from the slagheap to the pinched, packed street.

Remember

the procession of the old-young men,

It shall

never happen again.”

dole queue to corner and back again,

From the

pinched, packed streets to the peak of slag

In the

bite of the winters with shovel and bag,

With a

drooping fag [cigarette] and a turned up collar,

Stamping

for the cold at the ill lit corner

Dragging

through the squalor with their hearts like lead

Staring

at the hunger and the shut pit-head

Nothing

in their pockets, nothing home to eat.

Lagging

from the slagheap to the pinched, packed street.

Remember

the procession of the old-young men,

It shall

never happen again.”

After the

Reichstag fire, Hitler’s false flag operation, and the Vienna massacre which

followed it, Dylan’s poem ‘My world is pyramid’ would appear in New Verse in

December 1934 and in it he mourns the death of the hopes embodied in the

socialism of ‘Red Vienna’ and Dylan describes the city’s being ravaged by

vengeful Nazis as a crucifixion. It’s a poetic version of Picasso’s Guernica,

and his “Red in an Austrian volley,” contains the lines:

Reichstag fire, Hitler’s false flag operation, and the Vienna massacre which

followed it, Dylan’s poem ‘My world is pyramid’ would appear in New Verse in

December 1934 and in it he mourns the death of the hopes embodied in the

socialism of ‘Red Vienna’ and Dylan describes the city’s being ravaged by

vengeful Nazis as a crucifixion. It’s a poetic version of Picasso’s Guernica,

and his “Red in an Austrian volley,” contains the lines:

“I hear,

through dead men’s drums, the riddled lads,

Strewing

their bowels from a hill of bones,

Cry Eloi

to the guns…”

through dead men’s drums, the riddled lads,

Strewing

their bowels from a hill of bones,

Cry Eloi

to the guns…”

The

persistent caricature of Dylan (created in large part by the American media’s

response to him on his final US tour) as an apolitical self-destructive

bohemian drunk was misguided and when, in one of the first books to appear in

which he was mentioned, Dylan’s work was described as “apolitical” Dylan wrote

challengingly to its author, Henry Treece, to say,

persistent caricature of Dylan (created in large part by the American media’s

response to him on his final US tour) as an apolitical self-destructive

bohemian drunk was misguided and when, in one of the first books to appear in

which he was mentioned, Dylan’s work was described as “apolitical” Dylan wrote

challengingly to its author, Henry Treece, to say,

“Surely

it is evasive to say my poetry has no social awareness – no evidence of contact

with society; actually, ‘seeking kinship’ with everything… is exactly what I do

do”.

it is evasive to say my poetry has no social awareness – no evidence of contact

with society; actually, ‘seeking kinship’ with everything… is exactly what I do

do”.

Dylan was

to make his opinion of Treece’s book even more clear when a friend asked him to

inscribe a copy for him, and Dylan wrote in it ‘to hell with this stinking

book’.

to make his opinion of Treece’s book even more clear when a friend asked him to

inscribe a copy for him, and Dylan wrote in it ‘to hell with this stinking

book’.

One day

during my stay in the Crypt, Leon told me that he’d had a word with Dylan’s

closest friend, Vernon Watkins, and said that he’d persuaded Vernon to agree to

see me for lunch to talk about Dylan. “He was interested to know you’d heard

Dylan.”

during my stay in the Crypt, Leon told me that he’d had a word with Dylan’s

closest friend, Vernon Watkins, and said that he’d persuaded Vernon to agree to

see me for lunch to talk about Dylan. “He was interested to know you’d heard

Dylan.”

Leon

prepared me for the meeting by saying, “You have to be a bit careful. He’s very

religious is Vernon. He once leapt from a window in Cambridge to see if angels

would save him. Unfortunately, he was met by a sudden rush of gravity. Made a

full recovery though. Likes tennis very much, does Vernon. Tennis and the sea.

prepared me for the meeting by saying, “You have to be a bit careful. He’s very

religious is Vernon. He once leapt from a window in Cambridge to see if angels

would save him. Unfortunately, he was met by a sudden rush of gravity. Made a

full recovery though. Likes tennis very much, does Vernon. Tennis and the sea.

“But

you’d be interested because Dylan would always show Vernon his poems before

he’d show them to anyone else. Trusted him. Vernon has a tendency to quote

Blake all the time, “prayer is the study of art.” That’s the sort of thing he

comes out with. Had a breakdown once and got God.”

you’d be interested because Dylan would always show Vernon his poems before

he’d show them to anyone else. Trusted him. Vernon has a tendency to quote

Blake all the time, “prayer is the study of art.” That’s the sort of thing he

comes out with. Had a breakdown once and got God.”

This was

slightly disturbing, but Leon quickly corrected the impression he’d given by

saying that although Vernon had been “playing the mad hatter for a bit” he was

now “quite stable” adding, “you have to be really, don’t you, if you’re a bank

clerk.”

slightly disturbing, but Leon quickly corrected the impression he’d given by

saying that although Vernon had been “playing the mad hatter for a bit” he was

now “quite stable” adding, “you have to be really, don’t you, if you’re a bank

clerk.”

When the

time of the appointment which Leon kindly made for me had arrived, Leon picked

me up from the Crypt and led me across St Helen’s Road towards the rendezvous.

Detecting my adolescent apprehension (I was then just seventeen) he put his

hand on my shoulder and said reassuringly, “No need to be nervous. It’s an

article of faith with Vernon that he never thinks badly of anyone. You’ll be in

compassionate hands.”

time of the appointment which Leon kindly made for me had arrived, Leon picked

me up from the Crypt and led me across St Helen’s Road towards the rendezvous.

Detecting my adolescent apprehension (I was then just seventeen) he put his

hand on my shoulder and said reassuringly, “No need to be nervous. It’s an

article of faith with Vernon that he never thinks badly of anyone. You’ll be in

compassionate hands.”

|

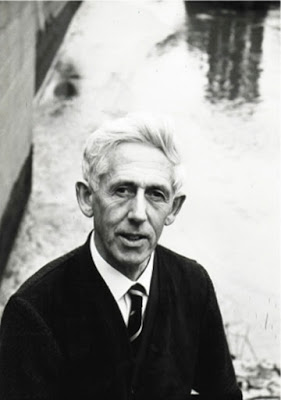

| Vernon Watkins |

He led me

into a tiny Italian restaurant next to the branch of Lloyds bank where Vernon

Watkins had worked for most of his life and where he was now the oldest serving

cashier. I got the impression that he ate here every day. Vernon was a shy,

elf-like man with pointed ears, at once jerkily spry and then quite immobile

like a lizard.

into a tiny Italian restaurant next to the branch of Lloyds bank where Vernon

Watkins had worked for most of his life and where he was now the oldest serving

cashier. I got the impression that he ate here every day. Vernon was a shy,

elf-like man with pointed ears, at once jerkily spry and then quite immobile

like a lizard.

He told

me that he had been under the spell of Yeats’s poetry all his life and that

he’d met Yeats and that he’d then written a poem about him into which he put

all the things that Yeats had said. Yeats had told him, Vernon said, that all

poems were “a piece of luck.”

me that he had been under the spell of Yeats’s poetry all his life and that

he’d met Yeats and that he’d then written a poem about him into which he put

all the things that Yeats had said. Yeats had told him, Vernon said, that all

poems were “a piece of luck.”

I asked

Vernon how Dylan had thought of his own poems and he said that Dylan had called

his own poems “statements on the way to the grave.” There was a doleful pause.

His remembering this seemed to trigger him off emotionally and his eyes welled

up. I wasn’t quite sure how to react. I think it was the first time I’d seen a

grown man weep.

Vernon how Dylan had thought of his own poems and he said that Dylan had called

his own poems “statements on the way to the grave.” There was a doleful pause.

His remembering this seemed to trigger him off emotionally and his eyes welled

up. I wasn’t quite sure how to react. I think it was the first time I’d seen a

grown man weep.

It had

only been seven years, in fact, since Dylan had died and while Vernon was

obviously pleased to talk enthusiastically about Dylan’s work, Dylan’s being

snatched away so dramatically and so many thousands of miles away at the age of

just 39 obviously still grieved him dreadfully. At what I imagined to be a

welter of unspoken memories pumping through his head he’d suddenly look

transfixed; hollow eyed and shattered. Then he’d press a napkin to his eyes,

dab his face and recover. He went on quietly:

only been seven years, in fact, since Dylan had died and while Vernon was

obviously pleased to talk enthusiastically about Dylan’s work, Dylan’s being

snatched away so dramatically and so many thousands of miles away at the age of

just 39 obviously still grieved him dreadfully. At what I imagined to be a

welter of unspoken memories pumping through his head he’d suddenly look

transfixed; hollow eyed and shattered. Then he’d press a napkin to his eyes,

dab his face and recover. He went on quietly:

“Dead

poets can be your contemporaries you know, that’s if the whole of the past is a

simultaneous experience, and it is. In which case…” He studied me closely,

“Dylan’s right here now, you see. He’s sat at this table. Not dead.” And then

he repeated it, quite insistently, as if it was a phenomenon that he often

experienced, “Not dead.”

poets can be your contemporaries you know, that’s if the whole of the past is a

simultaneous experience, and it is. In which case…” He studied me closely,

“Dylan’s right here now, you see. He’s sat at this table. Not dead.” And then

he repeated it, quite insistently, as if it was a phenomenon that he often

experienced, “Not dead.”

All of a

sudden we seemed to be having a kind of impromptu séance until he emerged from

it and was able to concentrate on his spaghetti and then on his lychees.

sudden we seemed to be having a kind of impromptu séance until he emerged from

it and was able to concentrate on his spaghetti and then on his lychees.

He was

like a slightly damaged schoolmaster, looking at you quite abstractly one

moment as if you weren’t there, and then examining you closely on your

knowledge of all the poets in Elysium; on all his personal familiars, on

Swinburne, on Milton, on Hopkins, and now on Thomas – all of whom he clearly

had intense relationships with. A kind of poets’ club, unconstrained by time;

all united in poetic ecstasies on Mount Parnassus.

like a slightly damaged schoolmaster, looking at you quite abstractly one

moment as if you weren’t there, and then examining you closely on your

knowledge of all the poets in Elysium; on all his personal familiars, on

Swinburne, on Milton, on Hopkins, and now on Thomas – all of whom he clearly

had intense relationships with. A kind of poets’ club, unconstrained by time;

all united in poetic ecstasies on Mount Parnassus.

Although

Vernon obviously kept some daunting imaginary company, I steeled myself and

passed him a poem that I’d written about the old man from the Gower Peninsula

and his rusting brass telescopes who was living in Leon’s Crypt. Vernon

unfolded it carefully, scrutinized it and then folded it back up and passed it

back without a word.

Vernon obviously kept some daunting imaginary company, I steeled myself and

passed him a poem that I’d written about the old man from the Gower Peninsula

and his rusting brass telescopes who was living in Leon’s Crypt. Vernon

unfolded it carefully, scrutinized it and then folded it back up and passed it

back without a word.

He ate

another lychee, mixing it with a half teaspoonful of vanilla ice cream. He then