SOME SURPRISES

A NAACP founder and future Communist who was always pro-Zionist

A civil rights leader who testified as to the good character of Ariel

Sharon

Sharon

The supposed article by Martin Luther King Jr. saying that to attack

Zionism was to attack Jews.

Zionism was to attack Jews.

Jesse Jackson’s increasingly meek statements on Israel

Malcolm X and a Trotskyite party

The remarkable Stokely Carmichael

***********************************************

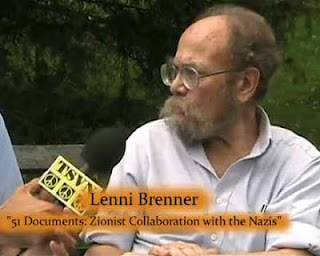

by Lenni Brenner

Zionist

Deals with Nazis and Fascists (part 1) Lenni Brenner

Deals with Nazis and Fascists (part 1) Lenni Brenner

If you asked today’s American college students when the civil rights

movement began, most would say “when Rosa Parks disobeyed a bus driver’s order

to give her seat to a white.” She was arrested on December 1, 1955. On December

5th, after her trial and the first day of the Black bus boycott, a meeting in

the Mt. Zion AME Church organized the Montgomery Improvement Association to

lead the struggle. Martin Luther King Jr. was elected its president. In 1957,

after strategy differences with King, Parks left Montgomery. She worked in

Detroit as a seamstress. In 1965, Democratic Representative John Conyers hired

her as his Detroit office secretary. She retired in 1988.

movement began, most would say “when Rosa Parks disobeyed a bus driver’s order

to give her seat to a white.” She was arrested on December 1, 1955. On December

5th, after her trial and the first day of the Black bus boycott, a meeting in

the Mt. Zion AME Church organized the Montgomery Improvement Association to

lead the struggle. Martin Luther King Jr. was elected its president. In 1957,

after strategy differences with King, Parks left Montgomery. She worked in

Detroit as a seamstress. In 1965, Democratic Representative John Conyers hired

her as his Detroit office secretary. She retired in 1988.

Americans easily understand the Montgomery Improvement Association’s

establishment in the Mt. Zion Church. Most Black Americans were religious. They

identified with the Hebrew slaves fleeing Egypt for “the promised land.” But,

beyond specialists in Black-Jewish relations, Parks’ subsequent employment by

by Conyers, a severe critic of Israel, and the later politics of the civil

rights movement is unknown to today’s public. Therefore this article will focus

on the evolution of America’s Black rights leaders and movements attitudes

towards Zionism, from the founding of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People in 1909, thru to 1994, when apartheid South

Africa, Israel’s open ally, vanished into history.

establishment in the Mt. Zion Church. Most Black Americans were religious. They

identified with the Hebrew slaves fleeing Egypt for “the promised land.” But,

beyond specialists in Black-Jewish relations, Parks’ subsequent employment by

by Conyers, a severe critic of Israel, and the later politics of the civil

rights movement is unknown to today’s public. Therefore this article will focus

on the evolution of America’s Black rights leaders and movements attitudes

towards Zionism, from the founding of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People in 1909, thru to 1994, when apartheid South

Africa, Israel’s open ally, vanished into history.

The Black Struggle from 1909 to WWII

When Parks was arrested, she was the secretary of the Montgomery chapter

of the NAACP. The national NAACP had only one Black, W.E.B. Du Bois, on its

first executive board in 1909. His politics and the NAACP’s evolved, eventually

in different ways, but he was always pro-Zionist.

of the NAACP. The national NAACP had only one Black, W.E.B. Du Bois, on its

first executive board in 1909. His politics and the NAACP’s evolved, eventually

in different ways, but he was always pro-Zionist.

“The African movement means to us what the Zionist movement must mean to

the Jews, the centralization of race effort and the recognition of a racial

fount.” [1]

the Jews, the centralization of race effort and the recognition of a racial

fount.” [1]

In its early years the NAACP organized occasional protest marches but

its primary arena soon became the courts. Post WW I, its place in the streets

was taken by Marcus Garvey’s ‘back to Africa’ Universal Negro Improvement

Association. Asked if he was imitating Benito Mussolini, he replied that

Mussolini was imitating him. But men in military formations were needed in an

era of anti-Black riots.

its primary arena soon became the courts. Post WW I, its place in the streets

was taken by Marcus Garvey’s ‘back to Africa’ Universal Negro Improvement

Association. Asked if he was imitating Benito Mussolini, he replied that

Mussolini was imitating him. But men in military formations were needed in an

era of anti-Black riots.

The UNIA grew to massive size until 1922, when Garvey was arrested for

mail fraud re money collected for his Black Star Line, which would ultimately

ship followers to Africa. Convicted in 1923, imprisoned in 1925, he was

deported to Jamaica in 1927. Garvey always equated the UNIA to Zionism, even

after blaming Jewish NAACP leaders for his prosecution.

mail fraud re money collected for his Black Star Line, which would ultimately

ship followers to Africa. Convicted in 1923, imprisoned in 1925, he was

deported to Jamaica in 1927. Garvey always equated the UNIA to Zionism, even

after blaming Jewish NAACP leaders for his prosecution.

Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks came to power in Russia in 1917 and

established the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, based on ethnic equality.

The Communist Party here made Black rights a top priority and attracted the

attention of Black intellectuals. After Lenin died in 1924, party secretary

Joseph Stalin converted the USSR into a personal dictatorship and the CPUSA

took his commands to be holy writ. Stalin and Communist parties everywhere,

including Palestine, opposed Zionism, but it was not an issue in their

involvement in the Black struggle.

established the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, based on ethnic equality.

The Communist Party here made Black rights a top priority and attracted the

attention of Black intellectuals. After Lenin died in 1924, party secretary

Joseph Stalin converted the USSR into a personal dictatorship and the CPUSA

took his commands to be holy writ. Stalin and Communist parties everywhere,

including Palestine, opposed Zionism, but it was not an issue in their

involvement in the Black struggle.

In 1928, the CPUSA called for a Black republic in the areas of the

American south where they were the majority. This attracted some Blacks, but

more important was the CP’s legal defense of the “Scottsboro boys,” nine young

Blacks convicted in Alabama in 1931 of raping two white women and sentenced to

death. The CP’s International Labor Defense took the case to the Supreme Court

which declared that defendants are entitled to effective counsel and that no

one may be de facto excluded from juries because of their race. White racist

rage against “Communists” and “Jewish lawyers” served to establish the

credibility of both among Blacks.

American south where they were the majority. This attracted some Blacks, but

more important was the CP’s legal defense of the “Scottsboro boys,” nine young

Blacks convicted in Alabama in 1931 of raping two white women and sentenced to

death. The CP’s International Labor Defense took the case to the Supreme Court

which declared that defendants are entitled to effective counsel and that no

one may be de facto excluded from juries because of their race. White racist

rage against “Communists” and “Jewish lawyers” served to establish the

credibility of both among Blacks.

In July 1930, Wallace D. Fard Muhammad founded the Nation of Islam in

Detroit. Among other things, it called for an independent Black state in

America. In 1933 he established a security guard called the Fruit of Islam to

defend the NOI and other Blacks against white racists.

Detroit. Among other things, it called for an independent Black state in

America. In 1933 he established a security guard called the Fruit of Islam to

defend the NOI and other Blacks against white racists.

Fard Muhammad left Detroit in 1934 and was never seen again. Before

departing he conferred leadership of the NOI on one of his earliest followers,

Elijah Poole, who changed his name to Elijah Muhammad. He preached that Wallace

Fard Muhammad was Islam’s Mahdi and Christianity’s Messiah. The Nation and FOI

were a small but visible presence in Black communities until the early 1950s,

when Malcolm X, who had converted while in prison for burglary, became Elijah

Muhammad’s chief lieutenant. Under Malcolm’s leadership the NOI became a mass

movement and the FOI grew in every Black community.

departing he conferred leadership of the NOI on one of his earliest followers,

Elijah Poole, who changed his name to Elijah Muhammad. He preached that Wallace

Fard Muhammad was Islam’s Mahdi and Christianity’s Messiah. The Nation and FOI

were a small but visible presence in Black communities until the early 1950s,

when Malcolm X, who had converted while in prison for burglary, became Elijah

Muhammad’s chief lieutenant. Under Malcolm’s leadership the NOI became a mass

movement and the FOI grew in every Black community.

It took the 1929 Depression, under a Republican President, to get

northern Blacks to vote for a Democrat, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in 1932, in hope

of improved economic conditions, but they had few illusions about their new

party. It ruled the legally racially segregated “solid south” and many northern

states where landlords and employers could discriminate or not, at their

option. There were no Black Democratic convention delegates until 1940.

northern Blacks to vote for a Democrat, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in 1932, in hope

of improved economic conditions, but they had few illusions about their new

party. It ruled the legally racially segregated “solid south” and many northern

states where landlords and employers could discriminate or not, at their

option. There were no Black Democratic convention delegates until 1940.

In 1934, Stalin anticipated a second world war with Britain, France, the

U.S. and the Soviets against Hitler. Unofficially, so as not to embarrass him,

the CP supported Roosevelt, putting it in tandem with Black voters. It was

central in organizing the Congress of Industrial Organizations, a rival to the

almost universally racist American Federation of Labor. Hundreds of thousands

of workers, many Black, joined CP-led unions. By 1939 the CP grew to 90,000

members, many Jewish or Black. Singer Paul Robeson, while not formally a CP

member, was royally treated in the Soviet Union and helped make the CP a major

force in the Black community.

U.S. and the Soviets against Hitler. Unofficially, so as not to embarrass him,

the CP supported Roosevelt, putting it in tandem with Black voters. It was

central in organizing the Congress of Industrial Organizations, a rival to the

almost universally racist American Federation of Labor. Hundreds of thousands

of workers, many Black, joined CP-led unions. By 1939 the CP grew to 90,000

members, many Jewish or Black. Singer Paul Robeson, while not formally a CP

member, was royally treated in the Soviet Union and helped make the CP a major

force in the Black community.

In 1938, Trinidad-born C.L.R. James, author of The Black Jacobins:

Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, came to the U.S. and

joined the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party. In 1939, under his influence,

the SWP declared that, if America’s Blacks wanted their own state in the south,

they would support the demand. The SWP was very small, but James’ book made him

well known to Black intellectuals, worldwide.

Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, came to the U.S. and

joined the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party. In 1939, under his influence,

the SWP declared that, if America’s Blacks wanted their own state in the south,

they would support the demand. The SWP was very small, but James’ book made him

well known to Black intellectuals, worldwide.

In 1939, after Britain and France signed the Munich pact with Hitler,

Stalin reversed himself and made the Hitler-Stalin pact. Thousands of Jews quit

the CP in disgust, but Bayard Rustin, a gay Black Quaker member of the Young

Communist League since 1936, stayed on. In 1941 the YCL assigned him to fight

against U.S. military segregation, then called off the campaign when the Nazis

invaded the Soviet Union. He quit in disgust and joined A. Philip Randolph

(1889 – 1979), president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, in calling

for a Black march on Washington against racial discrimination in war industries

and segregation in the military. The march was cancelled after Roosevelt issued

Executive Order 8802, banning war industry discrimination. The military

remained segregated, but the Executive Order was seen by many Blacks as a

partial victory.

Stalin reversed himself and made the Hitler-Stalin pact. Thousands of Jews quit

the CP in disgust, but Bayard Rustin, a gay Black Quaker member of the Young

Communist League since 1936, stayed on. In 1941 the YCL assigned him to fight

against U.S. military segregation, then called off the campaign when the Nazis

invaded the Soviet Union. He quit in disgust and joined A. Philip Randolph

(1889 – 1979), president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, in calling

for a Black march on Washington against racial discrimination in war industries

and segregation in the military. The march was cancelled after Roosevelt issued

Executive Order 8802, banning war industry discrimination. The military

remained segregated, but the Executive Order was seen by many Blacks as a

partial victory.

Rustin went to prison in 1944 for violating the WWII draft law. He could

have accepted a religious pacifist civilian work assignment, but chose prison,

feeling that his political opposition to war was more important than his

religious concerns.

have accepted a religious pacifist civilian work assignment, but chose prison,

feeling that his political opposition to war was more important than his

religious concerns.

The Cold War Era

With Hitler’s defeat, Democratic President Harry Truman faced a very

different enemy, foreign and domestic. The USSR was seen by many Blacks as for

their rights. Many thousands of Blacks were in CP-led unions. In 1947, Randolph

formed the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the

League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience. Truman had two concerns. If the U.S.

faced off militarily with any Communist foe, it would try to get Blacks in the

segregated military to mutiny, and he was hoping to get elected in 1948.

different enemy, foreign and domestic. The USSR was seen by many Blacks as for

their rights. Many thousands of Blacks were in CP-led unions. In 1947, Randolph

formed the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the

League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience. Truman had two concerns. If the U.S.

faced off militarily with any Communist foe, it would try to get Blacks in the

segregated military to mutiny, and he was hoping to get elected in 1948.

Vice President Truman became President when Roosevelt died in 1945. In

1948, one of his opponents was Henry Wallace, his predecessor as Roosevelt’s

Vice President (1941–1945). During anti-Black riots in Detroit in 1943, Wallace

declared that America couldn’t “fight to crush Nazi brutality abroad and

condone race riots at home.” Such politics were too left for Roosevelt and

he chose Senator Truman, front man for the notoriously corrupt Kansas City,

Missouri Democratic “machine,” to run with him in 1944. Every poll predicted

Truman’s defeat. If he lost enough Black votes to Wallace he was certain to

lose. So, on July 26, 1948, he abolished military racial segregation via

Executive Order 9981.

1948, one of his opponents was Henry Wallace, his predecessor as Roosevelt’s

Vice President (1941–1945). During anti-Black riots in Detroit in 1943, Wallace

declared that America couldn’t “fight to crush Nazi brutality abroad and

condone race riots at home.” Such politics were too left for Roosevelt and

he chose Senator Truman, front man for the notoriously corrupt Kansas City,

Missouri Democratic “machine,” to run with him in 1944. Every poll predicted

Truman’s defeat. If he lost enough Black votes to Wallace he was certain to

lose. So, on July 26, 1948, he abolished military racial segregation via

Executive Order 9981.

Wallace got only 2.4 percent of the national vote, but even after 9981

and a civil rights plank in the Democratic Party platform, the first in its

history, he received one third of the Black vote. Prominent Blacks supported

him including heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, singer Lena Horne, Robeson

and Du Bois. This led to the NAACP terminating Du Bois’ employment, but Zionism

wasn’t an issue in the rupture. The NAACP’s leaders were for Truman, who raced

Stalin to be the first to recognize the new Israeli state.

and a civil rights plank in the Democratic Party platform, the first in its

history, he received one third of the Black vote. Prominent Blacks supported

him including heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, singer Lena Horne, Robeson

and Du Bois. This led to the NAACP terminating Du Bois’ employment, but Zionism

wasn’t an issue in the rupture. The NAACP’s leaders were for Truman, who raced

Stalin to be the first to recognize the new Israeli state.

Wallace opposed the “cold war” and was running as the candidate of the

Progressive Party, created for the occasion by the CP. It maintained Lenin’s

anti-Zionist line until 1947, when Moscow suddenly declared its support for the

creation of Israel. The scholarly consensus is that Stalin wanted Britain,

Palestine’s Mandatory ruler, out of the Middle East. None of London’s Arab satraps

were interested in rebelling against their overlord and Stalin thought Zionist

success in kicking the British out would, somehow, force Britain’s Arab puppets

to try to do likewise.

Progressive Party, created for the occasion by the CP. It maintained Lenin’s

anti-Zionist line until 1947, when Moscow suddenly declared its support for the

creation of Israel. The scholarly consensus is that Stalin wanted Britain,

Palestine’s Mandatory ruler, out of the Middle East. None of London’s Arab satraps

were interested in rebelling against their overlord and Stalin thought Zionist

success in kicking the British out would, somehow, force Britain’s Arab puppets

to try to do likewise.

Until the late 40s, most Jewish men were blue collar workers. In the

30s, almost all Jewish union leaders opposed Zionism. When their bosses gave

donations to Zionist charities they felt that the money should have gone to

their members as wages. This changed dramatically after the Holocaust. A

nationalist wave swept through American Jewry. In Manhattan, thousands of Jews

and others marched and danced around the New York Times tower when its

electronic sign announced the creation of Israel. That demonstration was

organized by the CP and Black CPers were among the dancers.

30s, almost all Jewish union leaders opposed Zionism. When their bosses gave

donations to Zionist charities they felt that the money should have gone to

their members as wages. This changed dramatically after the Holocaust. A

nationalist wave swept through American Jewry. In Manhattan, thousands of Jews

and others marched and danced around the New York Times tower when its

electronic sign announced the creation of Israel. That demonstration was

organized by the CP and Black CPers were among the dancers.

There were two reasons why Truman overruled his “the Arabs got the oil”

oriented State Department and recognized the new state in 1948. In her book,

Harry S. Truman, his daughter Margaret related how “On October 6,1947, Bob

Hannegan,” the Democratic National Chairman,

oriented State Department and recognized the new state in 1948. In her book,

Harry S. Truman, his daughter Margaret related how “On October 6,1947, Bob

Hannegan,” the Democratic National Chairman,

“almost made a speech, pointing out how many Jews were major

contributors to the Democratic Party‘s campaign fund and were expecting the

United States to support the Zionists’ position on Palestine.” [2]

contributors to the Democratic Party‘s campaign fund and were expecting the

United States to support the Zionists’ position on Palestine.” [2]

The other reason was the Progressive Party’s strength among Jews and

Blacks in New York, the home state of Thomas Dewey, his pro-Zionist Republican

opponent. Truman feared that, unless he backed Zionism, rich Jews would fund

Dewey, Jewish workers would vote Progressive and he would lose the state. In

fact Truman did lose it but, to everyone’s amazement, won the national

election.

Blacks in New York, the home state of Thomas Dewey, his pro-Zionist Republican

opponent. Truman feared that, unless he backed Zionism, rich Jews would fund

Dewey, Jewish workers would vote Progressive and he would lose the state. In

fact Truman did lose it but, to everyone’s amazement, won the national

election.

Two years later, in 1950, Du Bois ran for the U.S. Senate as the

candidate of the American Labor Party, the Progressive Party’s New York

affiliate, and received almost 210,000 votes, and 12.8 per cent of Harlem’s

count.

candidate of the American Labor Party, the Progressive Party’s New York

affiliate, and received almost 210,000 votes, and 12.8 per cent of Harlem’s

count.

With Stalin it was always gyrations. His own pro-Zionist politics

generated enthusiasm for Israel among Soviet Jews which he equated with

disloyalty to him. In November 1948 he began a purge of “cosmopolitans,” almost

always with Jewish names or with their Jewish birth name in brackets next to

their later Russian name. On January 13, 1953, a group of doctors was accused

of being agents of a Zionist conspiracy to poison him and other Soviet leaders.

He died on March 5, 1953 and the new Soviet leadership exonerated the doctors

in a March 31 decree.

generated enthusiasm for Israel among Soviet Jews which he equated with

disloyalty to him. In November 1948 he began a purge of “cosmopolitans,” almost

always with Jewish names or with their Jewish birth name in brackets next to

their later Russian name. On January 13, 1953, a group of doctors was accused

of being agents of a Zionist conspiracy to poison him and other Soviet leaders.

He died on March 5, 1953 and the new Soviet leadership exonerated the doctors

in a March 31 decree.

Many Jews left the CPUSA, usually with their Times Tower politics and

pro-civil rights feelings intact. Those still loyal after 1953 simply used the

exoneration to wash away Stalin’s anti-Semitism and their zeal for him in that

period. Thereafter the CP supported the Soviet Union’s alliances with

Palestinian movements and Arab regimes, but it always opposed the call for a

democratic secular binational state. Party members and CP-led unions continued

to play important roles in the civil rights movement.

pro-civil rights feelings intact. Those still loyal after 1953 simply used the

exoneration to wash away Stalin’s anti-Semitism and their zeal for him in that

period. Thereafter the CP supported the Soviet Union’s alliances with

Palestinian movements and Arab regimes, but it always opposed the call for a

democratic secular binational state. Party members and CP-led unions continued

to play important roles in the civil rights movement.

Although Black voters backed pro-Zionist candidates, Israel wasn’t a

Black election issue in 1948. But on September 17, Sweden’s Count Folke

Bernadotte, the U.N. mediator in the Arab-Israeli conflict, was assassinated by

the Lohamei Herut Israel, Fighters for the Freedom of Israel (aka the Stern

gang), and Ralph Bunche, a Black American diplomat, took his place. He worked

out the 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan,

and Syria, establishing the armistice line between Israel and Jordan, now known

as the Green Line.

Black election issue in 1948. But on September 17, Sweden’s Count Folke

Bernadotte, the U.N. mediator in the Arab-Israeli conflict, was assassinated by

the Lohamei Herut Israel, Fighters for the Freedom of Israel (aka the Stern

gang), and Ralph Bunche, a Black American diplomat, took his place. He worked

out the 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan,

and Syria, establishing the armistice line between Israel and Jordan, now known

as the Green Line.

Most educated Blacks saw Bunche’s Armistice as sanctification of

Israel’s existence, especially so after 1950, when Bunche won the Noble Peace

Prize. This pro-Zionist spin was later reinforced when Bunche participated in

the 1963 March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery march that led to the

passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Israel’s existence, especially so after 1950, when Bunche won the Noble Peace

Prize. This pro-Zionist spin was later reinforced when Bunche participated in

the 1963 March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery march that led to the

passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

This same period also saw a rival left involvement in the civil rights

movement that produced what comes off today as amazing secular prophesy. In

1946-48, Daniel Guerin, a French Trotskyist, visited the southern U.S. In

Negroes on the March, copyright 1951, he assessed the NAACP:

movement that produced what comes off today as amazing secular prophesy. In

1946-48, Daniel Guerin, a French Trotskyist, visited the southern U.S. In

Negroes on the March, copyright 1951, he assessed the NAACP:

“In Mobile, Ala., an important industrial city, the NAACP branch

numbered 2,000 members when I was there, but I could not find a single worker

among them. One of the few places where I saw a branch with a relatively

proletarian composition was Montgomery, Ala.; the reason for this happy

exception was that the branch secretary was also a trade union

official….

numbered 2,000 members when I was there, but I could not find a single worker

among them. One of the few places where I saw a branch with a relatively

proletarian composition was Montgomery, Ala.; the reason for this happy

exception was that the branch secretary was also a trade union

official….

A living example of this evolution was presented to me by E.D. Nixon of

Montgomery, Ala., a vigorous colored union militant who was the leading spirit

in his city both of the local union of Sleeping Car Porters and the local

branch of the NAACP. What a difference from the other branches of the

Association, which are controlled by dentists, pastors and undertakers!”

[3]

Montgomery, Ala., a vigorous colored union militant who was the leading spirit

in his city both of the local union of Sleeping Car Porters and the local

branch of the NAACP. What a difference from the other branches of the

Association, which are controlled by dentists, pastors and undertakers!”

[3]

Leftist presence in the civil rights movement automatically meant FBI

spying. In June 1952, a CP informer brought Stanley Levison, a New York lawyer

and realtor, to the FBI’s attention. He was supposed to be a secret major CP

financier since the end of WWII. In 1955 he, Rustin and others set up In

Friendship to send money to southern Black activists.

spying. In June 1952, a CP informer brought Stanley Levison, a New York lawyer

and realtor, to the FBI’s attention. He was supposed to be a secret major CP

financier since the end of WWII. In 1955 he, Rustin and others set up In

Friendship to send money to southern Black activists.

Rustin introduced Levison to King in 1956 and he soon became King’s good

right hand. He set up the MIA’s first mail-solicitations for funds, and helped

King get the contract for his first book, Stride Towards Freedom, and wrote

parts of it. On September 20, 1958, King was stabbed by Izola Curry, a mad

Black woman, while promoting the book, and Levison became central to the

financing of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference while he

recovered.

right hand. He set up the MIA’s first mail-solicitations for funds, and helped

King get the contract for his first book, Stride Towards Freedom, and wrote

parts of it. On September 20, 1958, King was stabbed by Izola Curry, a mad

Black woman, while promoting the book, and Levison became central to the

financing of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference while he

recovered.

Levison drifted away from the CP before he met King. But he refused an

FBI request that he inform on the party and took the 5th Amendment when called

before a Senate committee. That made the Kennedy brothers and FBI Director J.

Edgar Hoover think that might he still might be a covert CPer. On June 22,

1963, President John Kennedy told King that he should drop Levison. He wouldn’t

abandon his confidant and, on October 10, 1963, Attorney General Robert

Kennedy, violating the 1st Amendment’s guarantees of freedom of religion and

speech, authorized wiretapping King. The FBI soon bugged his hotel rooms,

taping his extra-marital affairs. Eventually they sent the tapes to King,

hoping that they would drive him to suicide. [4] Spying continued until his

1968 assassination.

FBI request that he inform on the party and took the 5th Amendment when called

before a Senate committee. That made the Kennedy brothers and FBI Director J.

Edgar Hoover think that might he still might be a covert CPer. On June 22,

1963, President John Kennedy told King that he should drop Levison. He wouldn’t

abandon his confidant and, on October 10, 1963, Attorney General Robert

Kennedy, violating the 1st Amendment’s guarantees of freedom of religion and

speech, authorized wiretapping King. The FBI soon bugged his hotel rooms,

taping his extra-marital affairs. Eventually they sent the tapes to King,

hoping that they would drive him to suicide. [4] Spying continued until his

1968 assassination.

In reality, Levison had shifted his allegiance to the Zionist American

Jewish Congress and ran its Upper West Side Manhattan branch. This is

understandable, given his CP involvement during its Times Tower phase. Rabbi

Stephen Wise (1874–1949), founder of the American Jewish Congress in 1918, had

been a NAACP national board member since 1914, but many scholars, including

pro-Zionists, consider his Nazi era behavior disgraceful. According to Saul

Friedlander, “In the spring of 1941, Rabbi Wise had decided to impose a

complete embargo on all aid sent to Jews in occupied countries, in compliance

with the U.S. government’s economic boycott of the Axis powers.” [5] On

December 2, 1942, after reports of the slaughter in the Ukraine reached the

West, he wrote a letter to “Dear Boss,” Franklin Roosevelt, asking for a

meeting and informing him that “I have had cables and underground advices for

some months, telling of these things. I succeeded, together with the heads of

other Jewish organizations, in keeping them out of the press.” [6]

Jewish Congress and ran its Upper West Side Manhattan branch. This is

understandable, given his CP involvement during its Times Tower phase. Rabbi

Stephen Wise (1874–1949), founder of the American Jewish Congress in 1918, had

been a NAACP national board member since 1914, but many scholars, including

pro-Zionists, consider his Nazi era behavior disgraceful. According to Saul

Friedlander, “In the spring of 1941, Rabbi Wise had decided to impose a

complete embargo on all aid sent to Jews in occupied countries, in compliance

with the U.S. government’s economic boycott of the Axis powers.” [5] On

December 2, 1942, after reports of the slaughter in the Ukraine reached the

West, he wrote a letter to “Dear Boss,” Franklin Roosevelt, asking for a

meeting and informing him that “I have had cables and underground advices for

some months, telling of these things. I succeeded, together with the heads of

other Jewish organizations, in keeping them out of the press.” [6]

When Peter Bergson, a rival Zionist, organized a “They Shall Never Die”

pageant to mobilize pressure on Roosevelt to rescue Jews, the AJC kept it out

of auditoriums wherever it could. [7] Du Bois and Randolph signed Bergson’s

newspaper ads and Walter White, then the NAACP Director, spoke at his 1943

Emergency Conference to Save the Jewish People of Europe.

pageant to mobilize pressure on Roosevelt to rescue Jews, the AJC kept it out

of auditoriums wherever it could. [7] Du Bois and Randolph signed Bergson’s

newspaper ads and Walter White, then the NAACP Director, spoke at his 1943

Emergency Conference to Save the Jewish People of Europe.

There is no evidence that Levison knew this when he joined AJC, or that

he was its agent in the civil rights movement. On the contrary, he was King’s

‘agent’ in getting support from the Jewish establishment. King knew that few

southern Jews joined the civil rights movement, but declared that “the national

Jewish bodies have been most helpful.” [8]

he was its agent in the civil rights movement. On the contrary, he was King’s

‘agent’ in getting support from the Jewish establishment. King knew that few

southern Jews joined the civil rights movement, but declared that “the national

Jewish bodies have been most helpful.” [8]

The night before his murder, he famously proclaimed that he had “been to

the mountaintop…. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with

you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the

promised land.” In fact he had actually been to Palestine.

the mountaintop…. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with

you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the

promised land.” In fact he had actually been to Palestine.

In 1959, under the influence of Rustin and the Quakers, King went to

Mohandas Gandhi’s Indian birthplace to study satyagraha, Gandhi’s resistance to

tyranny through mass civil disobedience. He returned via Jordan and visited

Jericho and Jerusalem‘s “old city.” It was then impossible to go to through the

Mandelbaum Gate between the Israeli and Jordanian sectors of Jerusalem, and he

returned home by way of Egypt and Greece, but the visit and the fact that he

couldn’t go through the checkpoint remained prominent in his thinking. Indeed

he referred to his traveling the road from Jericho to Jerusalem – where a

Biblical Hebrew was rescued by a good Samaritan, after other Jews ignored his

misery – in his last, immortal, speech.

Mohandas Gandhi’s Indian birthplace to study satyagraha, Gandhi’s resistance to

tyranny through mass civil disobedience. He returned via Jordan and visited

Jericho and Jerusalem‘s “old city.” It was then impossible to go to through the

Mandelbaum Gate between the Israeli and Jordanian sectors of Jerusalem, and he

returned home by way of Egypt and Greece, but the visit and the fact that he

couldn’t go through the checkpoint remained prominent in his thinking. Indeed

he referred to his traveling the road from Jericho to Jerusalem – where a

Biblical Hebrew was rescued by a good Samaritan, after other Jews ignored his

misery – in his last, immortal, speech.

In 1961 W.E.B. Du Bois joined the American Communist Party, became a

citizen of Ghana and, still pro-Zionist, died there in 1963, only days before

King’s celebrated “I have a dream” speech. King was the greatest American

orator since Lincoln, but Rustin put together the speakers list for the massive

August 28, 1963 March on Washington. King spoke immediately after Joachim Prinz

(1902-1988), President of the AJC, 1958–1966:

citizen of Ghana and, still pro-Zionist, died there in 1963, only days before

King’s celebrated “I have a dream” speech. King was the greatest American

orator since Lincoln, but Rustin put together the speakers list for the massive

August 28, 1963 March on Washington. King spoke immediately after Joachim Prinz

(1902-1988), President of the AJC, 1958–1966:

“When I was the rabbi of the Jewish community in Berlin under the Hitler

regime, I learned many things. The most important thing that I learned… was

that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problems. The most urgent…

and the most tragic problem is silence.” [9]

regime, I learned many things. The most important thing that I learned… was

that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problems. The most urgent…

and the most tragic problem is silence.” [9]

In reality he had been an eager collaborator with Nazism. In 1937, in

America, he wrote about Germany. His article described the Zionist mood in

1933:

America, he wrote about Germany. His article described the Zionist mood in

1933:

“The government announced very solemnly that there was no country in the

world which tried to solve the Jewish problem as seriously as did Germany.

Solution of the Jewish question? It was our Zionist dream! We never denied the

existence of the Jewish question! Dissimilation? It was our own appeal! … In

a statement notable for its pride and dignity, we called for a conference.”

[10]

world which tried to solve the Jewish problem as seriously as did Germany.

Solution of the Jewish question? It was our Zionist dream! We never denied the

existence of the Jewish question! Dissimilation? It was our own appeal! … In

a statement notable for its pride and dignity, we called for a conference.”

[10]

On February 8, 1981, I interviewed him.

Brenner: “What made you think that you could represent the Jews in

dealing with the Nazi government?”

dealing with the Nazi government?”

Prinz: “Oh, we thought, in our discussions with intellectuals in the SS

movement, that the time would come when they would say, ‘Yes, you live in

Germany, you are Jewish people, you are different from us, but we will not kill

you, we will permit you to live your own cultural life, and develop your own

national capacities and dreams.’ We thought, at the beginning of the Hitler

regime that such a very frank discussion was possible. We found among the SS

intellectuals, some people were ready for such a talk. But of course such a

talk never took place because the radical element in the Nazi movement won

out.” [11]

movement, that the time would come when they would say, ‘Yes, you live in

Germany, you are Jewish people, you are different from us, but we will not kill

you, we will permit you to live your own cultural life, and develop your own

national capacities and dreams.’ We thought, at the beginning of the Hitler

regime that such a very frank discussion was possible. We found among the SS

intellectuals, some people were ready for such a talk. But of course such a

talk never took place because the radical element in the Nazi movement won

out.” [11]

How did a wannabe collaborator with Hitler come to speak with King? As I

was leaving, after the taped interview, he told me that “When I got to America,

everything I believed in Germany sounded crazy to me.” I’ve never doubted his

honesty. The 1963 rabbi was very different from the 1933 rabbi, and Rustin and

King knew nothing about that rabbi. They, like most Jews and gentiles of that

era, knew little of Zionism’s history.

was leaving, after the taped interview, he told me that “When I got to America,

everything I believed in Germany sounded crazy to me.” I’ve never doubted his

honesty. The 1963 rabbi was very different from the 1933 rabbi, and Rustin and

King knew nothing about that rabbi. They, like most Jews and gentiles of that

era, knew little of Zionism’s history.

Although the March was massive, Malcolm X called it a “farce.” On

October 11, 1963 Malcolm spoke outdoors to thousands at the University of

California’s Berkeley campus. The NOI’s representative had nothing good to say

about the racially integrationist civil rights movement. But after the rally,

with the microphone off, two men went up to the podium. I heard one say, in

accented English, “Minister Malcolm, we think your talk was very good. But we

are from Iran, a Muslim country. There is nothing about race in the Koran or

Islam.” Malcolm looked at them, without moving or saying a word, for over a

minute, until a U.C. official took his arm and led him off the podium.

October 11, 1963 Malcolm spoke outdoors to thousands at the University of

California’s Berkeley campus. The NOI’s representative had nothing good to say

about the racially integrationist civil rights movement. But after the rally,

with the microphone off, two men went up to the podium. I heard one say, in

accented English, “Minister Malcolm, we think your talk was very good. But we

are from Iran, a Muslim country. There is nothing about race in the Koran or

Islam.” Malcolm looked at them, without moving or saying a word, for over a

minute, until a U.C. official took his arm and led him off the podium.

On November 22, President Kennedy was assassinated. On December 1,

Malcolm was asked about it and declared it “chickens coming home to roost” and

Elijah Muhammad ordered him silent for three months. During that period Malcolm

heard rumors about Muhammad’s extramarital affairs with young secretaries. On

March 8, 1964, he announced his break from the NOI, claiming Muhammad confirmed

the rumors. He converted to Sunni Islam, and set up the Organization of

Afro-American Unity, a secular Black nationalist movement.

Malcolm was asked about it and declared it “chickens coming home to roost” and

Elijah Muhammad ordered him silent for three months. During that period Malcolm

heard rumors about Muhammad’s extramarital affairs with young secretaries. On

March 8, 1964, he announced his break from the NOI, claiming Muhammad confirmed

the rumors. He converted to Sunni Islam, and set up the Organization of

Afro-American Unity, a secular Black nationalist movement.

On March 26, he met King at a Senate debate on the Civil Rights bill

outlawing unequal voter registration requirements, racial segregation in

schools, workplaces and public accommodations. They were photographed warmly

smiling and shaking hands. [12]

outlawing unequal voter registration requirements, racial segregation in

schools, workplaces and public accommodations. They were photographed warmly

smiling and shaking hands. [12]

In April he went to Mecca, saw those Iranians were correct, visited

several Arab and Black African countries and returned to the U.S., eager to

work with all races for worldwide human rights. The SWP asked him to speak at

its New York Militant Forum and he did so three times. He and the SWP discussed

having its Young Socialist Alliance organize a national college tour for him.

Then, on February 21, 1965, he was assassinated by members of the NOI at a

public OAAU meeting.

several Arab and Black African countries and returned to the U.S., eager to

work with all races for worldwide human rights. The SWP asked him to speak at

its New York Militant Forum and he did so three times. He and the SWP discussed

having its Young Socialist Alliance organize a national college tour for him.

Then, on February 21, 1965, he was assassinated by members of the NOI at a

public OAAU meeting.

America’s Blacks were outraged. The Harlem NOI mosque was torched and

NOI members were attacked in other places. Tens of thousands viewed his body

before his funeral. Rustin and Andrew Young from SCLC, John Lewis from the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, were among many civil rights leaders

at the televised wake. Actor Ossie Davis delivered an acclaimed eulogy for

“our shining black prince.” King telegrammed Betty Shabazz,

expressing sadness over “the shocking and tragic assassination of your

husband. While we did not always see eye to eye on methods to solve the race

problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt that he had a great

ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem.”

[13]

NOI members were attacked in other places. Tens of thousands viewed his body

before his funeral. Rustin and Andrew Young from SCLC, John Lewis from the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, were among many civil rights leaders

at the televised wake. Actor Ossie Davis delivered an acclaimed eulogy for

“our shining black prince.” King telegrammed Betty Shabazz,

expressing sadness over “the shocking and tragic assassination of your

husband. While we did not always see eye to eye on methods to solve the race

problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt that he had a great

ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem.”

[13]

After his death, the SWP’s Pathfinder Press published many of Malcolm’s

speeches and their evaluations of his development. They saw his strengths and

weaknesses:

speeches and their evaluations of his development. They saw his strengths and

weaknesses:

“At a press conference held on the day of his return to New York…. he

was also asked if he still thought Negroes should return to Africa…. Malcolm

X replied that after speaking to African leaders he was convinced that ‘If

Black men become involved in a philosophical, cultural and psychological

migration back to Africa, they will benefit greatly in this country.’ He

compared this to the benefits that Jews had derived from their identification

with Israel.”

was also asked if he still thought Negroes should return to Africa…. Malcolm

X replied that after speaking to African leaders he was convinced that ‘If

Black men become involved in a philosophical, cultural and psychological

migration back to Africa, they will benefit greatly in this country.’ He

compared this to the benefits that Jews had derived from their identification

with Israel.”

Editor George Breitman cited “overgenerous remarks Malcolm made about

Prince Feisal, who had shown Malcolm extraordinary courtesies in an emotionally

tense period during his trip to Mecca…. Malcolm did fail, on occasion, to

differentiate sufficiently between revolutionary and non revolutionary African,

Arab and Asian leaders.”

Prince Feisal, who had shown Malcolm extraordinary courtesies in an emotionally

tense period during his trip to Mecca…. Malcolm did fail, on occasion, to

differentiate sufficiently between revolutionary and non revolutionary African,

Arab and Asian leaders.”

But Breitman was correct. “The Last Year of Malcolm X” was indeed “The

Evolution of a Revolutionary.” [14] His trip to Mecca converted him into an

intense personal cosmopolitan and he realized that the SWP, a central element

in the anti-Vietnam war movement, had a lot to teach him re the political side

of that world view.

Evolution of a Revolutionary.” [14] His trip to Mecca converted him into an

intense personal cosmopolitan and he realized that the SWP, a central element

in the anti-Vietnam war movement, had a lot to teach him re the political side

of that world view.

Martin Luther King, Black Power, Black Panthers and Zionism

That leftward evolution didn’t stop with Malcolm. Growing out of a

February 1, 1960 Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth’s sit-in, the Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) played a central

role in the sit-ins, freedom rides and racially integrated voter registration

drives over the next years. Its Chairman, John Lewis, prepared to make the most

radical speech at the 1963 Washington march, including

February 1, 1960 Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth’s sit-in, the Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) played a central

role in the sit-ins, freedom rides and racially integrated voter registration

drives over the next years. Its Chairman, John Lewis, prepared to make the most

radical speech at the 1963 Washington march, including

“Kennedy is trying to take the revolution out of the streets and put it

in the courts. Listen Mr. Kennedy, the black masses are on the march for jobs

and for freedom, and we must say to the politicians that there won’t be a

‘cooling-off period.'” [15]

in the courts. Listen Mr. Kennedy, the black masses are on the march for jobs

and for freedom, and we must say to the politicians that there won’t be a

‘cooling-off period.'” [15]

The Kennedy administration put pressure on Rustin and this statement was

deleted from his speech but it reflected SNCC’s ever growing radicalism.

deleted from his speech but it reflected SNCC’s ever growing radicalism.

On the West Coast, Huey Newton heard me speak during the 1963 Cuban

missile crisis. On October 16, 1964, he introduced himself to me in Oakland,

California, in jail. Over four days we spent two hours discussing America, the

civil rights movement, Marxism and Vietnam, but didn’t discuss Zionism.

However, his Black Panther Party, founded on October 15, 1966, was anti-Zionist

and worked with left Jews and other whites inside the Peace and Freedom Party.

They called themselves Panthers from the ballot logo of SNCC’s Alabama Lowndes

County Freedom Organization, in 1966 known for “Black Power” and

anti-Zionism.

missile crisis. On October 16, 1964, he introduced himself to me in Oakland,

California, in jail. Over four days we spent two hours discussing America, the

civil rights movement, Marxism and Vietnam, but didn’t discuss Zionism.

However, his Black Panther Party, founded on October 15, 1966, was anti-Zionist

and worked with left Jews and other whites inside the Peace and Freedom Party.

They called themselves Panthers from the ballot logo of SNCC’s Alabama Lowndes

County Freedom Organization, in 1966 known for “Black Power” and

anti-Zionism.

It was Trinidad-born Stokely Carmichael, SNCC’s chair after Lewis, who

converted it into a Black organization and put “Black Power” into America’s

political lexicon in a June 16, 1966 speech in Greenwood, Mississippi, but he

always said he wasn’t the one who converted SNCC to anti-Zionism.

converted it into a Black organization and put “Black Power” into America’s

political lexicon in a June 16, 1966 speech in Greenwood, Mississippi, but he

always said he wasn’t the one who converted SNCC to anti-Zionism.

Born in 1941, he came to the New York at 11, after his mother proved

that she was born in the Panama Canal Zone when it was governed by the U.S. He

graduated from the world’s best high school. In his posthumous book, Ready For

Revolution, he told us that

that she was born in the Panama Canal Zone when it was governed by the U.S. He

graduated from the world’s best high school. In his posthumous book, Ready For

Revolution, he told us that

“At Bronx Science, I attended study camps with the Young Socialists and

Young Communist groups. Here I learned to sing ‘Hava Nagella’ and to dance the

hora. During the fifties, these young-left groups were unquestioningly

pro-Zionist. Stalin had given arms to Zionist factions in 1948, and Israel was

said to be progressive. End of story. There was no discussion at all of the

rights of the Palestinian people. None.” [16]

Young Communist groups. Here I learned to sing ‘Hava Nagella’ and to dance the

hora. During the fifties, these young-left groups were unquestioningly

pro-Zionist. Stalin had given arms to Zionist factions in 1948, and Israel was

said to be progressive. End of story. There was no discussion at all of the

rights of the Palestinian people. None.” [16]

His transition to anti-Zionism “was due almost entirely to the work of

one courageous activist sister.” To protect her from retaliation, he never

named her, but scholars say it was Ethel Minor, SNCC’s communications director.

After college,

one courageous activist sister.” To protect her from retaliation, he never

named her, but scholars say it was Ethel Minor, SNCC’s communications director.

After college,

“She met Palestinians…. She began to investigate the issue…. she

followed Malcolm into the Organization of Afro-American Unity. After his

assassination, the sister joined SNCC, where she organized a study group on the

question…. We found, to my surprise, that a great deal of the most incisive

and persuasive critical writing was by Jewish writers.” [17]

followed Malcolm into the Organization of Afro-American Unity. After his

assassination, the sister joined SNCC, where she organized a study group on the

question…. We found, to my surprise, that a great deal of the most incisive

and persuasive critical writing was by Jewish writers.” [17]

His biggest shock “was discovering the close military, economic, and

political alliance between the Israeli government and the racist apartheid

regime in South Africa.” [18]

political alliance between the Israeli government and the racist apartheid

regime in South Africa.” [18]

He related how “war was declared on SNCC” when the press reported a SNCC

anti-Zionist position paper:

anti-Zionist position paper:

“No other civil rights organization had a position on the Middle East,

and there were clear reasons for that. A good deal of their financial support

came from mainstream liberals, quite often from progressive elements of the

Jewish community…. So obviously there would be a price to pay…. But as Dr.

King said, ‘There comes a time when silence is tantamount to consent.’”

[19]

and there were clear reasons for that. A good deal of their financial support

came from mainstream liberals, quite often from progressive elements of the

Jewish community…. So obviously there would be a price to pay…. But as Dr.

King said, ‘There comes a time when silence is tantamount to consent.’”

[19]

King said that in 1967, re the Vietnam war. But in 1966 he was among the

civil rights leaders who denounced the notion of Black power, calling it “an

unfortunate choice of words.” [20] And he only agreed to speak at an April 15,

1967 anti-war rally at the U.N. if Carmichael wasn’t allowed to speak. The

organizers accepted his condition but then invited Carmichael, who spoke and

led a marching group carrying Vietcong flags. By then King was so anti-war

that, according to Murray Friedman’s 1995 What Went Wrong: The Creation and

Collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance, they went to Harry Belafonte’s home,

where the three “exchanged views on future plans.” [21] We don’t know more

about what they discussed, but Friedman and subsequent scholars understood that

future joint public appearances would have served to further legitimatize

Carmichael’s anti-Zionism, regardless of King’s personal opinion re

Israel.

civil rights leaders who denounced the notion of Black power, calling it “an

unfortunate choice of words.” [20] And he only agreed to speak at an April 15,

1967 anti-war rally at the U.N. if Carmichael wasn’t allowed to speak. The

organizers accepted his condition but then invited Carmichael, who spoke and

led a marching group carrying Vietcong flags. By then King was so anti-war

that, according to Murray Friedman’s 1995 What Went Wrong: The Creation and

Collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance, they went to Harry Belafonte’s home,

where the three “exchanged views on future plans.” [21] We don’t know more

about what they discussed, but Friedman and subsequent scholars understood that

future joint public appearances would have served to further legitimatize

Carmichael’s anti-Zionism, regardless of King’s personal opinion re

Israel.

“Black Power” made Carmichael so famous that, three decades later, the

Times reported his cancer diagnosis. This generated a 1996 letter from

Anti-Defamation League National Director Abraham Foxman:

Times reported his cancer diagnosis. This generated a 1996 letter from

Anti-Defamation League National Director Abraham Foxman:

“Re your laudatory news article on Kwame Toure, formerly Stokely

Carmichael (March 1): While working for civil rights is admirable, there is

another side to Mr. Toure’s career that the article did not convey. Mr. Toure

is an unabashed racial separatist and anti-Semite who often uses the slogan

‘the only good Zionist is a dead Zionist.’ His visits to college campuses have

been followed by acts of anti-Semitism and violence.” [22]

Carmichael (March 1): While working for civil rights is admirable, there is

another side to Mr. Toure’s career that the article did not convey. Mr. Toure

is an unabashed racial separatist and anti-Semite who often uses the slogan

‘the only good Zionist is a dead Zionist.’ His visits to college campuses have

been followed by acts of anti-Semitism and violence.” [22]

I wrote the paper a letter, accompanied by an article by Carmichael. The

Times called me. “Thank you very much for your letter.” It ran on March

16:

Times called me. “Thank you very much for your letter.” It ran on March

16:

“As a Jewish leftist who worked with Mr. Toure against the Iraq war, I

insist that he is not anti-Semitic. Mr. Toure’s nuanced position was expressed

in the May 1991 Anti-War Activist newsletter…. ‘Africans must transform the

anti-war movement to an anti-capitalist and anti-Zionist movement…. The

Zionists tried to chastise [Nelson] Mandela for his support for the P.L.O….

They control our community’s politicians. Look how they work harder for Israel

than for Azania-South Africa! We must properly distinguish between Judaism and

Zionism.’”

insist that he is not anti-Semitic. Mr. Toure’s nuanced position was expressed

in the May 1991 Anti-War Activist newsletter…. ‘Africans must transform the

anti-war movement to an anti-capitalist and anti-Zionist movement…. The

Zionists tried to chastise [Nelson] Mandela for his support for the P.L.O….

They control our community’s politicians. Look how they work harder for Israel

than for Azania-South Africa! We must properly distinguish between Judaism and

Zionism.’”

Mr. Toure’s hatred of Zionism, not Judaism or Jews is justified. Nathan

Perlmutter, Mr. Foxman’s predecessor at the Anti-Defamation League, has written

about why the organization would not join the group Trans-Africa in its

demonstration against apartheid:

Perlmutter, Mr. Foxman’s predecessor at the Anti-Defamation League, has written

about why the organization would not join the group Trans-Africa in its

demonstration against apartheid:

‘I cannot ignore the fact that the [African National] Congress’s

literature is anti-Israel, highly sympathetic to the P.L.O. cause and tolerate

of cooperation with the South African Communist Party. The lesson for us as

Jews is not to engage our emotions in indignation about evil empires like South

Africa. I think we too have a responsibility to determine whether or not that

which stands in line to replace a current regime is better for the Jews or

worse for the Jews’.” [23]

literature is anti-Israel, highly sympathetic to the P.L.O. cause and tolerate

of cooperation with the South African Communist Party. The lesson for us as

Jews is not to engage our emotions in indignation about evil empires like South

Africa. I think we too have a responsibility to determine whether or not that

which stands in line to replace a current regime is better for the Jews or

worse for the Jews’.” [23]

Did the Times caller’s “thank you” speak for its editors? No, but he

certainly spoke for many of its readers, relieved that a civil rights icon

hadn’t become anti-Semitic. In any case, the Times 1998 obit, “Stokely

Carmichael, Rights Leader Who Coined ‘Black Power,’ Dies at 57,” heaped

criticism on him, including King’s “an unfortunate choice of words,” and threw

in a few praises: “Tall, slim, handsome…. Carmichael was arrested so often as

a nonviolent volunteer that he lost count after 32…. a spellbinding orator,”

but the obit said nothing re his anti-Zionism. [24]

certainly spoke for many of its readers, relieved that a civil rights icon

hadn’t become anti-Semitic. In any case, the Times 1998 obit, “Stokely

Carmichael, Rights Leader Who Coined ‘Black Power,’ Dies at 57,” heaped

criticism on him, including King’s “an unfortunate choice of words,” and threw

in a few praises: “Tall, slim, handsome…. Carmichael was arrested so often as

a nonviolent volunteer that he lost count after 32…. a spellbinding orator,”

but the obit said nothing re his anti-Zionism. [24]

The Times may not have known of the Belafonte meeting. It certainly

didn’t know of their last meeting. In 1968, the Washington Post warned King

that Carmichael would turn the Poor People’s Campaign into rioting. But, in

2003, Ready For Revolution told us that

didn’t know of their last meeting. In 1968, the Washington Post warned King

that Carmichael would turn the Poor People’s Campaign into rioting. But, in

2003, Ready For Revolution told us that

“When Dr. King came into D.C., I went to see him. Of course I assured

him that I and SNCC would never do anything to… jeopardize the campaign. He

said, ‘Stokely, you don’t need to tell me that. I know you.’ I told him that

Washington SNCC would organize the local community, the street people and youth

gangs – to make sure they were cool. He said he’d appreciate that…. As I was

leaving, he held onto my hand, looking worried. ‘Stokely, please be extra

careful now. Avoid any unnecessary risks. Promise me.’ I recall laughing….

King repeated his warning…. Very soon I’d have reason to remember his mood at

our last meeting.” [25]

him that I and SNCC would never do anything to… jeopardize the campaign. He

said, ‘Stokely, you don’t need to tell me that. I know you.’ I told him that

Washington SNCC would organize the local community, the street people and youth

gangs – to make sure they were cool. He said he’d appreciate that…. As I was

leaving, he held onto my hand, looking worried. ‘Stokely, please be extra

careful now. Avoid any unnecessary risks. Promise me.’ I recall laughing….

King repeated his warning…. Very soon I’d have reason to remember his mood at

our last meeting.” [25]

Attorney General Eric Holder spoke at SNCC’s 50th year reunion in 2010.

Knowing that Israel’s alliance with apartheid until its end is known to many

Blacks, Holder didn’t utter a word against Carmichael.

Knowing that Israel’s alliance with apartheid until its end is known to many

Blacks, Holder didn’t utter a word against Carmichael.

In 1967, Nobel Peace Prize winner King signed a Times ad just before the

June “six-day war,” calling on the U.S. to back Israel. But, according to

Friedman,

June “six-day war,” calling on the U.S. to back Israel. But, according to

Friedman,

“In a conversation with Levison and his other New York advisers the

following day, King admitted to being confused. He had never actually seen the

ad before it appeared, he told them. When he did, he was not happy with it. He

felt it was unbalanced and pro-Israel, although he observed that it would

probably help with the Jewish community…. his advisers, even the Jewish ones,

suggested in effect that King carry water on both shoulders. Since war settles

nothing, as Levison put it, King could adapt a peace position without taking

sides. While agreeing that the territorial integrity of Israel and its right to

be a homeland were incontestable, King should urge a peace position without

taking sides. King should urge that all other questions be settled by

negotiations. Such a position, said Levison, would serve to keep the Arab

friendship and the Israeli friendship. King agreed to it.”

following day, King admitted to being confused. He had never actually seen the

ad before it appeared, he told them. When he did, he was not happy with it. He

felt it was unbalanced and pro-Israel, although he observed that it would

probably help with the Jewish community…. his advisers, even the Jewish ones,

suggested in effect that King carry water on both shoulders. Since war settles

nothing, as Levison put it, King could adapt a peace position without taking

sides. While agreeing that the territorial integrity of Israel and its right to

be a homeland were incontestable, King should urge a peace position without

taking sides. King should urge that all other questions be settled by

negotiations. Such a position, said Levison, would serve to keep the Arab

friendship and the Israeli friendship. King agreed to it.”

A month later he proposed “a pilgrimage of blacks and whites to the Holy

Land.” He worried “that the Arab world, and probably Africa and Asia too, would

interpret the action as endorsing everything that Israel had done and he did

have doubts.” Andrew Young “chipped in that he felt it important that King

develop a strong point of view and personal contact with the Middle East

situation since the Arab position had never had a hearing in this country,

Levison agreed.”

Land.” He worried “that the Arab world, and probably Africa and Asia too, would

interpret the action as endorsing everything that Israel had done and he did

have doubts.” Andrew Young “chipped in that he felt it important that King

develop a strong point of view and personal contact with the Middle East

situation since the Arab position had never had a hearing in this country,

Levison agreed.”

Months later King wrote “a four-page letter to the president of the

American Jewish Committee.” He had spoken at a Chicago New Politics convention.

“Jewish agencies asked King to disavow the malevolent language” after he left.

“He indicated that had he stayed he would have reiterated the SCLC stand…

Israel’s right to exist as a state was incontestable.” [26]

American Jewish Committee.” He had spoken at a Chicago New Politics convention.

“Jewish agencies asked King to disavow the malevolent language” after he left.

“He indicated that had he stayed he would have reiterated the SCLC stand…

Israel’s right to exist as a state was incontestable.” [26]

King’s public statements pleased Zionists, and rabbi Abraham Heschel was

on the podium when King gave his powerful April 4, 1967 New York Riverside

Church anti-Vietnam war speech. But rabbi Marc Schneier’s Shared Dreams: Martin

Luther King, Jr. & The Jewish Community, tells us that King’s oration

created a problem for

on the podium when King gave his powerful April 4, 1967 New York Riverside

Church anti-Vietnam war speech. But rabbi Marc Schneier’s Shared Dreams: Martin

Luther King, Jr. & The Jewish Community, tells us that King’s oration

created a problem for

“major Jewish organizations. Though most disliked the war, they were

extremely cautious in their public opposition to it, since President Johnson

had warned them that any anti-war stands from them would jeopardize American

support for Israel.”

extremely cautious in their public opposition to it, since President Johnson

had warned them that any anti-war stands from them would jeopardize American

support for Israel.”

Schneier writes that

“Johnson liked having things his way. If you disagreed with him, he was

likely to find a sore point to which he could apply the pressure until you

complied with his wishes. For Jews, Israel was that sore point.

likely to find a sore point to which he could apply the pressure until you

complied with his wishes. For Jews, Israel was that sore point.

Never saying it outright, Johnson strongly implied to several key

Congressional and Jewish leaders that Jewish opposition to the war could

trigger cuts in American military and economic aid to Israel. It was a trump

card.” [27]

Congressional and Jewish leaders that Jewish opposition to the war could

trigger cuts in American military and economic aid to Israel. It was a trump

card.” [27]

King’s April 4, 1968 assassination came at a crossroad in his relations

with Washington and American Zionism. He was publicly pro-Israel but met with

Carmichael against Johnson’s war and for King’s Poor Peoples Campaign, as the

Zionist establishment silently moved from him towards Johnson. They didn’t

identify with his Poor People’s Campaign aimed at bringing poor Blacks, Whites,

Indians and Hispanics to Washington. The establishment wasn’t helping him in

Memphis, Tennessee when he died supporting Black sanitation workers, striking

for higher wages and racially equal treatment. “The most important thing that I

learned… was that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problems. The

most urgent… and the most tragic problem is silence.” That’s what Prinz said

in 1963, but they were silent about that strike.

with Washington and American Zionism. He was publicly pro-Israel but met with

Carmichael against Johnson’s war and for King’s Poor Peoples Campaign, as the

Zionist establishment silently moved from him towards Johnson. They didn’t

identify with his Poor People’s Campaign aimed at bringing poor Blacks, Whites,

Indians and Hispanics to Washington. The establishment wasn’t helping him in

Memphis, Tennessee when he died supporting Black sanitation workers, striking

for higher wages and racially equal treatment. “The most important thing that I

learned… was that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problems. The

most urgent… and the most tragic problem is silence.” That’s what Prinz said

in 1963, but they were silent about that strike.

The murder generated Black riots across the U.S. and Johnson, who loved

listening to tapes of King’s sex, had to declare him a martyr. Since then the

Zionist establishment has loudly publicized its marching with him in 1963, even

while, as Zionist John Rothman reports, “For some Jews, Nixon’s support for

Israel was the litmus test. Yitzhak Rabin actively campaigned for him in 1972,

when Nixon got 37 percent of the Jewish vote, up from 19 percent in 1968.”

[28]

listening to tapes of King’s sex, had to declare him a martyr. Since then the

Zionist establishment has loudly publicized its marching with him in 1963, even

while, as Zionist John Rothman reports, “For some Jews, Nixon’s support for

Israel was the litmus test. Yitzhak Rabin actively campaigned for him in 1972,

when Nixon got 37 percent of the Jewish vote, up from 19 percent in 1968.”

[28]

‘King loved Israel, Israel loved him’ propaganda has reached enormous

proportions. Israel has an official ML King day and forest. Schneier, chair of

the World Jewish Congress’s American Section, tells of “an article that

appeared in the Saturday Review two months after the [1967] war ended.”

According to Schneier, King wrote:

proportions. Israel has an official ML King day and forest. Schneier, chair of

the World Jewish Congress’s American Section, tells of “an article that

appeared in the Saturday Review two months after the [1967] war ended.”

According to Schneier, King wrote:

“You declare, my friend, that you do not hate the Jews, you are merely

‘anti-Zionist.’ And I say, let the truth ring forth from the high mountain

tops, let it echo through the valleys of God’s green earth.When people

criticize Zionism, they mean the Jews — this is God’s own truth. Anti-Semitism

… has been and remains a blot on the soul of mankind. In this we are in full

agreement. So know also this: anti-Zionist is inherently anti-Semitic, and ever

will be so.” [29]

‘anti-Zionist.’ And I say, let the truth ring forth from the high mountain

tops, let it echo through the valleys of God’s green earth.When people

criticize Zionism, they mean the Jews — this is God’s own truth. Anti-Semitism

… has been and remains a blot on the soul of mankind. In this we are in full

agreement. So know also this: anti-Zionist is inherently anti-Semitic, and ever

will be so.” [29]

Schneier’s gives his source as “King, ‘Letter to an Anti-Zionist

Friend,’ Saturday Review, 47 (August 1967), 76. Reprinted in King, This I

Believe: Selections from the Writings of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York,

1971), 234-235.” [30]

Friend,’ Saturday Review, 47 (August 1967), 76. Reprinted in King, This I

Believe: Selections from the Writings of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York,

1971), 234-235.” [30]

Except that this writer and Harlem’s Schomberg Library couldn’t locate

the Letter or “This I Believe.” At my request, The Journal of Palestine Studies

and the Library of Congress also sought and couldn’t discover them. On March

15, at a public meeting in New York’s Queens University, I asked Schneier to

locate the Letter for me. “Contact my office.” I emailed his Foundation for Ethnic

Understanding, waited, then phoned: “We got your email. We’re not supposed to

talk to you.”

the Letter or “This I Believe.” At my request, The Journal of Palestine Studies

and the Library of Congress also sought and couldn’t discover them. On March

15, at a public meeting in New York’s Queens University, I asked Schneier to

locate the Letter for me. “Contact my office.” I emailed his Foundation for Ethnic

Understanding, waited, then phoned: “We got your email. We’re not supposed to

talk to you.”

Off the record, Hoover had told some Congress Representatives and others

about Levison and King’s sex life. After King’s April 1968 assassination, a

journalist revealed that Robert Kennedy, then running in Democratic primaries

to replace Johnson, had authorized wiretapping King, but there wasn’t much

public focus on this. Then, on June 5, Kennedy was shot by Sirhan Sirhan, a

Palestinian Christian.

about Levison and King’s sex life. After King’s April 1968 assassination, a

journalist revealed that Robert Kennedy, then running in Democratic primaries

to replace Johnson, had authorized wiretapping King, but there wasn’t much

public focus on this. Then, on June 5, Kennedy was shot by Sirhan Sirhan, a

Palestinian Christian.

Except for the usual conspiracy buffs, his jailers and today’s scholars

agree that he did it on his own. But the assassination drew the public’s

attention away from the tapping of King, and turned Kennedy into a Democratic

martyr. With time, details of the wiretapping emerged, but today perhaps the

best example of the party’s hypocrisy is its simultaneous iconic treatment of

King and the two villains who spied on him.

agree that he did it on his own. But the assassination drew the public’s

attention away from the tapping of King, and turned Kennedy into a Democratic

martyr. With time, details of the wiretapping emerged, but today perhaps the