The Bund, the General Jewish Workers Union of Russia, Lithuania and Poland is not a word or name that is mentioned in most Zionist households. Most Jewish kids grow up completely oblivious to their existence. But if you are a Zionist anorak, and have read something about the origins of the movement you support (& very few have!) then you understand that there was no bitterer foe of Zionism than the Bund. If you read, for example, the biography of Ben Gurion (Shabtai Teveth – The Burning Ground – 1886-1948) you will see that the Bund was always the main enemy of the Zionists in Poland where most East European Jews lived.

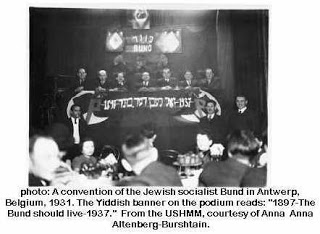

Formed in 1897 in Lithuania the Bund helped form the Russian Social Democratic Party, which spawned the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks. But from the time of its formation, the Bund grew to have more members than the rest of the RSDLP put together, at least until it walked out in 1903 over the question of autonomy.

There is no need to revisit those old debates about whether the Bund had the right to represent all Jewish workers, regardless of whether they wished to be associated with the Bund (which many early Jewish communists did not). They are irrelevant to today.

What cannot be denied is that the Bund stood for all the things – brotherhood & sisterhood of all workers, for a socialist society where the earth’s resources are shared in common, the common fight against fascism and dictatorship – that Zionism rejected. The Bund represented the growing Jewish working class whereas Zionism, with their bourgeois morning suits at their first Congress, sought the friendship of the Czar’s Ministers and every anti-Semitic aristocrat in Europe.

The Bund led the self-defence of the Jews in the Pale of Settlement, to which the Jews were confined by Czarist Russia. The Czarist regime, under Nicholas II in particular, sponsored and subsidised the Black Hundreds pogromists and sought consciously to divide Russian workers and peasants from their Jewish counterparts.

Because of the attacks by the Czarist regime, Jewish workers rapidly became politicised, far more so than their non-Jewish neighbours. Some 50% of all arrests of revolutionaries were Jewish and thus was born the myth that Bolshevism was a Jewish creation. It was this that sparked off Hitler’s hatred of the Jews – that they had inspired Bolshevism – not the other way around.

It was therefore a great surprise when I received a round robin announcing that a new film of the Bund in Israel by Eran Torbiner had been produced. Although I knew that a few members of the Bund had settled in Israel after the holocaust, I didn’t realise that they had kept their organisation intact.

Members of the Bund in Israel to this day consider themselves either anti-Zionist or non-Zionist. To them the Bund’s universalism and ideas of joint struggles between all workers, stand in sharp contrast to the particularism and exclusivism of Zionism. Indeed this has helped hold the group together, but as Torbiner shows in his film and as the Ha’aretz article depicts, most of the members are in their ‘80s and ‘90s. What we are witnessing is a piece of history that will soon be no more. If only for that we should be grateful for this film.

This film and the ideas behind it give the lie to those who suggest that Israel and Zionism are the product of some mysterious ‘Jewishness’. That racism against Arabs and Palestinians is inherent in being Jewish. A film like this can give an understanding of the crimes that Zionism has committed against Jews, let alone Palestinians. Whereas being Jewish was seen as being progressive and radical up to the early 1950’s, today the term ‘Jewish’ is synonymous with imperialism, neo-conservatism, invasion, bombing of civilians, false accusations of racism, economic privilege and overt anti-Muslim racism. Who recalls that one of only two Communist MPs elected in Britain, was Phil Piratin for Mile End in the East End post-1945?

Zionism has literally buried a whole swathe of Jewish history beneath its reactionary nationalism and its Jewish anti-Semitism (because the worst anti-Semites today are Zionists).

This film is about rediscovering that past and it is to be hoped that it will be shown in a large number of towns and that groups involved in Palestine solidarity will also put on showings. It also has a relevance to today. As Eran Torbiner wrote to me in response to a query of mine:

“As a socialist I’m also anti-Zionist and support the boycott from within. Part of the Bundists in my film are totally Anti Zionists, and others prefer to identify themselves as Non Zionist. You will feel and see it in the film. I’ll be happy of course if you will find the film useful for political events.’

This isn’t just a cultural artifact but helps people see that Israel is the product, not of something peculair to Jews and Jewish racial traits, but capitalism and its colonialist and imperialist offshoots. Zionism’s success was in turning Jews from being seen as the oppressed into the oppressor – but at what cost? See this film.

Tony Greenstein

Film on the Bund in Israel

Dear comrades and friends,

On May Day 2006 I was invited to celebrate with the members of the ‘Bund’ in Israel, I took my video camera and thought it will be a one-time occasion but it became a five and half year political and personal journey.

Unlike my previous films (‘Matzpen’ and ‘Madrid before Hanita’, about the volunteers to the International Brigades in Spain), my requests for financial support from funding bodies and broadcasters were rejected.

Despite this, I knew I had to continue filming, researching and editing. Finally, today, through the support of some friends, modest financial support from Yiddish and research institutes and many loans I succeeded in completing the film.

I’m happy to say that the last survivors of the ‘Bund’ like it very much and I’m very proud of it.

Attached is a link to the opening of the film: (see also below)

Technical note:

The length of the film is 48 minutes, it’s with English and Hebrew subtitles (The languages in the film are Hebrew and Yiddish) and it’s in PAL, The Broadcasting system in Europe and Israel. Those of you from North America will be able to watch it on your computers.

I’m offering you to order this DVD for 100 NIS / 20€ / $30) which includes shipping. Supporting the film by ordering more than one copy or paying a higher price would be greatly appreciated.

You can send payment by credit card using www.paypal.com (click on “send money”) my account is [email protected] or if you prefer you can send a cheque to my address. I’ll send you the DVD immediately. Please forward this e-mail to friends who might be interested.

In solidarity

Eran Torbiner

Shulamit 8

Tel-Aviv 64371

Israel

Published 29 July 2011 (Hebrew)

Attending the recent 60th anniversary celebration of the Israeli branch of the secular, socialist Bund organization was like taking a shortcut to a lost past, into a preserve detached from local time.

It’s best to start from the end: from the recent 60th anniversary celebrations of the Israeli Bund and its Yiddish-language journal Lebns Fragn (Life Questions ). This story needs to begin at the end, even though the end is not happy and has no point or moral. But it is the end, if only temporary, of a story that began in a Vilna attic in 1897 and is fading out in a building at the corner of Kalischer and Nahalat Binyamin Streets in Tel Aviv. There in Tel Aviv, on May 25, the absolutely last members of the Bund – the General Jewish Workers’ Alliance – gathered to mark 60 years. At its peak, before World War II, the organization had tens of thousands of members and supporters, mainly in Poland but also in other countries. The last remnants of the Bund, most of them in the ninth decade of their lives, still make an effort to meet here, in the Arbeyter-Ring (Workers’ Alliance ) hall, every two weeks. At those meetings, they sit around tables set for a meal, listen with deep concentration to a live choir and to a talk and speak almost always in Yiddish and about Yiddish.

It’s not by chance that this entirely secular gathering resembles a quorum congregating in a beit midrash (house of study ) on the anniversary of the death of a righteous man. The Bund may have no God, but it does have its saints, and the passage of time has also sanctified the past: Indeed, the Bundists constantly evoke its memories. Maybe that’s why a religiously observant Jew wearing a skullcap was able to infiltrate the 60th anniversary celebrations of the Israeli branch of the group – because few of the militant socialist secular Bundists are still with us. In any event, their principal representative in this hall is Yitzhak Luden, a red-headed youngster despite his 87 years and encroaching white hair.

Outside, it’s a regular Wednesday morning. The textile carts of Nahalat Binyamin – the gentrified shopping area adjacent to the Carmel market in the old city center – cause traffic jams and provoke drivers to honk and curse, but inside the Bund House a festive quiet prevails, and worldwide congratulations for the editor of its journal resonate.

This is a moment of deep satisfaction and uplifting of the spirit, which will disperse clouds of anxiety – at least until the next meeting in two weeks. I myself gave a talk here a few months back, a fact that I note here not (only ) to brag about, but for the sake of full disclosure: I know this audience well.

Climbing the stairs of the building on Kalischer Street is like taking a shortcut to a lost past, and the windowless, neon-lit hall feels like a preserve detached from Israeli time. I strain to close the generation gap and walk among the rearguard of the defeated, against this place, whose members used to march in military parades with the arrogant feeling of the victorious. True, the way to the past is full of obstacles and dangerous, and it’s natural for languages to become extinct every day. Still, I cling to these people, who adamantly safeguard the “language that was exiled to doom,” in the words of the poet Avoth Yeshurun.

So I was surprised, a few months ago, to discover among the local Bundists, a young man (he’s 40, but age is a relative concept ) filming the proceedings with great interest. “That’s Eran Torbiner,” people whispered to me.

Afterward, when we were introduced, I understood that he too is interested in various kinds of veterans: In 2003 he made a film about the now-defunct Israeli anti-Zionist organization Matzpen, and in 2006 he made “Madrid Before Hanita,” a documentary about Jews in Palestine who volunteered in the International Brigade that fought on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War.

In making the latter movie, Torbiner seized the last moment at which it was possible to talk to the volunteers before they all passed away. Sinilarly, he started to shoot his latest film, “Bundaiim” (“Bundists” ) five years ago, and since then many of the interviewees have died. But he does not belong to those who lament the loss of Yiddish; he looks mainly at the socialist side of the Bund. His new film, lovely and elegiac, opens with the May Day ceremony in 2006 and the singing of the “Internationale” in Yiddish.

“My first connection with them was because of the Yiddish,” he says. “They reminded me of my grandparents, who arrived here at a relatively late age and used to sit with their friends in parks in Bat Yam, speak Yiddish and look after the grandson. I heard them, I felt them. But that is not a reason to make a film. The reason is the Bund’s political ideas. Afterward, when I met the Bundists for interviews, I fell in love with them.’

“My subject, in almost all my films,” Torbiner continues, “is deep and true socialism, of the kind I found in the Bund’s writings. All the people I interviewed for this film are first of all socialists. They speak socialist-ese, and only afterward Yiddish. Socialism comes first for them, even before the Jewish national identity. That is a legitimate and respectable identity, but it is not connected to the primary goal. That goal is for all human beings to be equal, worthy and decent.;

“In ‘Matzpen’ and ‘Madrid before Hanita,’ I made films about a minority within a minority. This time the subject constitutes a very central stream: In 1930s Poland, the Bund was a very significant presence on the Jewish street. The majority of that country’s three million Jews did not speak Hebrew and were not Zionists. They spoke Yiddish. That was my grandfather’s mother tongue; he was a leather worker, a simple laborer. The Bund was not out to forge an elitist socialism of avant-garde groups. These people understood that it was necessary to appeal to the people in their language: Yiddish.”

A distinctive federation

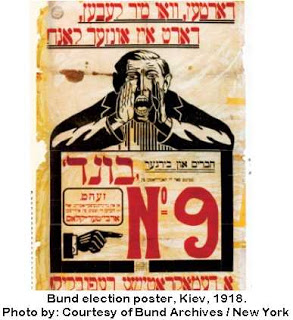

This was precisely the motivation for the founding in 1897 of the Bund in Vilna, part of the Jewish Pale of Settlement in czarist Russia, where some 40 percent of the world’s Jews lived. The Bund is shorthand for Der Algemeyner Yiddisher Arbeyter Bund in Lite, Polyn un Rusland (literally, General Union of Jewish Workers in Lithuania, Poland and Russia ). Its aim was encapsulated in its declaration – namely to create “a distinctive Jewish federation of workers, which will lead and educate the Jewish proletariat in its battle for economic, civil and political liberation.”

The Bund was revolutionary in every sense with regard to its responses to czarist rule, the class war and Jewish secularism. In its early years the organization oscillated between a socialist vision and Jewish nationalism, and tended toward socialism in its pure form. Vladimir Medem, one of the Bund’s first ideologues, formulated its neutral stance: “We are not against assimilation, we are against the pursuit of assimilation, against assimilation as a goal.”

But in 1903 the organization, which supported Jewish autonomy, withdrew from the congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Party.

“Two great ideas are incorporated in the solution put forward by the Austrian Social-Democrats for the national problem,” the Bund organ Der Yiddisher Arbeyter (The Jewish Worker ) wrote in December 1899. “The first is that all the nations are equal and that the proletariat desires its national culture, language and literature to continue to develop. The second idea: to draw a distinction between nation and land; that not only a people that has a territory can demand national rights. Instead of the old rule – ‘the people and its land’ – we advocate ‘the people and its culture.'”

Ultimately, after disputes and division – the nationalists to the right, the socialists to the left – the Bund articulated the concept that there was no contradiction: In its vision, each entity would be an equal member of the family of nations. Underlying this approach was the proposition that there are no nations of greater or lesser worth – in other words, the seminal Jewish principle, “You chose us from among all the nations,” was discarded.

Unwaveringly secularist in its beliefs, the Bund also relinquished the idea of the Holy Land and the sacred tongue. Its language was Yiddish, spoken by millions of Jews throughout the Pale. This was also the source of the organization’s four principles: socialism, secularism, Yiddish and doyikayt or “localness.” The latter concept was encapsulated in the Bund slogan: “There, where we live, that is our country.”

“Unwaveringly secularist in its beliefs,

the Bund also relinquished the idea of

the Holy Land and the sacred tongue. ”

After the Bolshevik Revolution, the Bund too underwent a revolution: The organization and its ideas were outlawed in the Soviet Union, while in independent Poland, established in 1919, the Bund for the first time became legal – more or less. It immediately launched vigorous activity among Polish Jewry – organizing its trade unions, struggling for the rights of the workers and also educating them, including women in the framework of the progressive Organization of Female Jewish Workers. But its main focus was on youth, the future generation of the largest and most vital Jewish public.

In cooperation with other, like-minded organizations, the Bund established the Central Yiddish School Organization (TSYSHO ), whose aim was to be the “antithesis to the Jewish religious educational tradition,” and instead to use a secular and socialist approach. The authors of the new history books that TSYSHO put out and used (all of them in Yiddish, as were those about other subjects ) tried “to integrate Jewish history and general history, to stir identification with national heroes without being dragged into nationalism,” according to historian Yaad Biran, who researched the subject for his master’s thesis. Thus, a Bund history textbook describes King Solomon in these words: “What did the king normally do? Either he waged wars and suppressed other peoples, or he waged war and suppressed his people.”

The Bund sought to implement the most modern educational ideas in the Medem Sanatorium, an institution which it built in a resort town outside Warsaw. Yitzhak Luden, a pupil there, wrote: “At the bottom line, its educational concept was based on an ideological principle: to be a healthful Jewish educational institution that will make the child healthy in body and mind and serve as an exemplary model for a democratic, egalitarian ‘republic of children’ and be administered by the children themselves.”

Hearts and minds

The Bund also excelled in combating anti-Semitism in Poland, organizing what it called “self-defense,” as well as strikes and mass demonstrations and protests against a law that restricted kosher slaughter. True, the Bund preferred to cooperate with non-Jewish socialist parties – such as the Polish Socialist Party or the minority Ukrainian and Belarus socialist parties in Poland – but the impression among the Jewish public still was that the Bund represented it. Thus, in 1938 this radical group garnered 40 percent of the Jewish votes in the elections to the councils of the big cities in Poland. “The Jews felt that someone was doing battle on their behalf,” Luden says. “They found an attentive ear in the Bund and shared a common language with it.”

“in 1938 this radical group garnered 40 percent

of the Jewish votes in the elections to the councils

of the big cities in Poland.”

Despite the harsh plight of Polish Jewry, particularly from the mid-1930s, the Bund’s future looked rosy. “I was a yeshiva student in Warsaw,” says Aharon Shapira, 92, a veteran of the organization now living in Carmiel, who is also interviewed in Torbiner’s film. “My parents’ home was very poor and I had to go to work. There I discovered a new and exciting world and I became a Bundist and socialist in body and mind.”

Shapira explains that he joined the Arkady group, which was part of the Bund and made a special effort to attract yeshiva students: “That was the future: democracy and Jewish autonomy. We fought for a better tomorrow. Thanks to the Bund I became an authentic person. Religion was then losing its strength. There were many religious people in Poland, yes, but the young generation was beginning to be liberated from religion and be educated for a life of freedom.”

One stubborn obstacle confronted the Bund: Zionism. Like the Bund, the modern Zionist movement was also born in 1897 and offered solutions to the same problem, but the two groups hated each other like Jacob and Esau.

“The Zionist idea – to bring about Jewish emigration and establish a national home in Palestine – was actually far more radical than the Bundist notion of Jewish autonomy in Eastern Europe,” researcher Biran notes. “Thus Zionism, like other national-liberation movements, preferred a romanticized conception of the past, according to which it would create a new common denominator for the Jews. In order to negate the present, Zionism had to internalize anti-Semitic stereotypes: to criticize the deteriorating life of Eastern European Jews and offer this Diaspora-style redemption. The danger was that romanticized nationalism was liable to deteriorate into fascism – because, if we are good and special, we have the right to take action in defense of our wonderful identity.”

Of course, the rivalry between the Bund and Zionism was not only ideological; it was also a struggle for the hearts and minds of the Jewish public. Even if Polish Jews could not, or did not want to immigrate en masse to Palestine, they were not indifferent to the possibility of realizing the dream of “next year in Jerusalem.”

‘Everyone’s victory’

At the ceremony marking the 60th anniversary of the Bund’s activity in Israel, historian Prof. Danny Gutwein called for the merging of the two movements. Filmmaker Torbiner, speaking before the screening of his new movie, vehemently objected to this idea.

“It is impossible to integrate them, because Zionism proposes an exclusivist solution and the Bund proposes equality,” Torbiner explains. “The victory of the Bund is everyone’s victory, whereas the victory of Zionism is the victory of itself and the defeat of the others.”

Wiktor Alter, a Bund leader in the interwar period, visited this country in 1924 and returned to Poland with a detailed report, which was published in book form as “The Truth about Palestine” (a play on the essay of the Zionist harbinger Ahad Ha’am, “Truth from the Land of Israel” ). Clearly Alter was out to besmirch the Jewish community in Palestine, but his book nevertheless offers crucial insights, some still relevant, such as his view that the Arab question is the most important issue in this part of the world.

At the time of Alter’s visit, Palestine’s population was 85 percent Arab and 11 percent Jewish, and he was astonished and outraged by the Zionist desire to become a majority and rule over the Arabs. In regard to socialism, too, Alter believed that the impoverished country did not offer the economic conditions necessary for a revolution – even the kibbutzim only looked after their own, he wrote. Inevitably, he explained, when those communities will be faced with the question of “whether it is more important to create 20 moshavot (colonies ) or to forge a strong workers’ movement” – they will choose the first option.

Alter was naturally also critical of the negation of Yiddish. “How can a person discard the satisfaction of the self that resides in his mother tongue?” he asked, and added, “They want to forget their old milieu completely; what’s important is to create a new person from themselves.”

Within a short time, he summed up: “Palestine will become an ordinary Diaspora” – for “the only true salvation in regard to the Jewish question is socialism.”

Bourgeois socialism

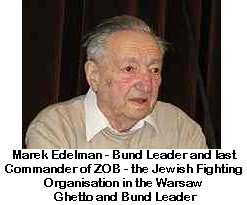

As everyone knows, the Bundist hope of bringing salvation to the Jewish people by means of socialism was soon dashed. Beginning in September 1939, the organization was persecuted by the Nazis and the Soviets alike. Leaders Alter and Henryk Erlich, who fled to the Soviet Union, were incarcerated and died there; other leading figures remained in Poland and took part in uprisings (Marek Edelman in the Warsaw Ghetto, for example ). Most of the organization’s supporters perished in the Holocaust.

“What happened to the Bund?” Aharon Shapira reiterates in an angry, or perhaps sad, tone, during our conversation. “The same thing that happened to all the other Jews. They were all murdered. Both the Bundists and the Zionists. The Zionist Mordechai Anielwicz perished along with the Bundist Avraham Blum. Whoever was in Palestine was spared, thanks to Field Marshal Montgomery’s defeat of Rommel.”

The Holocaust survivors (less than 10 percent of prewar Polish Jewry ) who tried to rehabilitate Jewish life in Poland failed abjectly. The pogroms of 1946 were a boon to Zionist propaganda and spurred large numbers of Jews to flee the country to DP camps on the way to Palestine. The Bundists tried to cling to Poland, but in 1948 the new communist government again outlawed the organization.

The Bund was vanquished, Zionism was triumphant; Israel came into being in the wake of the Holocaust. But was the victor also in the right?

“Zionism was always built from catastrophes,” Luden says. And Torbiner adds,

The lesson that’s drawn in Israel from the Holocaust is that we cannot trust anyone and we have to be strong. Because we are the ‘ultimate’ persecuted people, we are permitted to do everything. That is more or less what [Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu said to the U.S. Congress not long ago, and drew wild applause. My lesson, in the wake of the Bund, is a message of partnership. The Nazis were stopped by the Allies, not by the Zionist movement, and it was not the Jewish people but the whole world that lost out in the Holocaust.”

If the masses – the future hope of the Bund – had not been murdered in the Holocaust, would the organization’s vision been realized? Prof. Avraham Novershtern, a scholar of Yiddish culture at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who is himself descended from a Bundist family, is skeptical: “The claim that the Holocaust is to blame for the destruction of the Bund is a half-truth. After all, many Bundists went to America or other places where they were not affected directly by the Holocaust, yet the Bund did not have continuity there.

“There was a systemic failure in the Bund which the Holocaust exacerbated,” Novershtern says, “but this situation had existed earlier. The failure has to do with the realization of utopia: What would ensure the Jewish people’s existence in the socialist future, when everyone is equal? The Bund, too, was fed by catastrophes. That is, as long as there was distress in Poland, it could propose joint action to improve the situation. But the likelihood is that if Poland had been cleansed of its anti-Semitic poison and had developed into a liberal country, the result would have been a process of integration and assimilation, as occurred in the free countries of immigration.

“After the situation of the Jews became better, the Bund no longer had ‘living space.’ I remember the meetings in honor of it, in Buenos Aires. The participants, all of them bourgeoisie, in suits and ties, sang the Bund anthem, which begins with the words, ‘Brothers and sisters in toil and want.’ In that regard they were no different from the members of Mapai [the forerunner of today’s Israel Labor Party], who sang the ‘Internationale.’

“In the eyes of the Bund,” Novershtern continues, “the common denominator was Yiddish, with all the culture that entails. But it’s been proved that language cannot be a national ‘cement’ for a minority – certainly not in a socialist society. Nor is there place in such a society for Jewish secularism, which can exist in the Diaspora for only one generation. And it goes without saying that the Bund did not create a version of Jewish socialism of the kind that is based on the vision of the prophets, for example.”

Closed club

For many of the Bundists who survived the Holocaust, there was no longer a possibility of a Jewish-secular-socialist future. A case in point is Aharon Shapira, who believed optimistically before the war that his own move from traditional Judaism to the Bund reflected a mass movement, but became an inveterate pessimist.

“After the war there was a plague of religion,” he says today. “The Almighty was victorious again. The same Almighty who watched as six million Jews were murdered nevertheless became the master once again. Go figure how the world works.”

Despite this, Luden says, “After the Holocaust and the state’s establishment the Bund recognized that Israel is a positive element, as a place of haven for the Jews.”

Accordingly, and perhaps because there was no other choice, he and his comrades came to this country. Arriving in their wake was Issachar Artuski, from Paris, the editor of the Bund journal Undzer Shtime (Our Voice ). In 1966, he recalled that the organization’s congress in Brussels in 1949 decided “to accede to the request of the members in Israel to establish a Bund organization there. Because I belonged to the ‘pro-Israel’ Bundists, it was suggested that I should lead activities there. I accepted this proposal with mixed feelings. I decided to go for a year, as a tourist, but when I arrived here, in 1950, I immediately plunged into the work and have stayed on to this day.”

The Israeli Bund, a mutual aid association, was established in May 1951. It put out its own monthly magazine, Lebns Fragn, and set up a Yiddish library, a choir and a drama circle. The Bund also tried to pursue educational activities, organizing children’s summer camps and even a Yiddish after-school program.

“One of the Bund’s qualities is the familial character that developed among its members – a kind of brotherhood of the persecuted,” Novershtern notes. “But that hampered the effort to increase its membership beyond the prewar Bundists. They were unable to recruit new supporters or members of the second generation. The Bund remained primarily a movement of people from Poland, who continued their activity out of inertia and nostalgia.”

“You cannot judge them,” Biran declares. “In the political circumstances of nascent Israel, it’s a miracle that the Bund even managed to exist here. Suddenly, after the wave of immigration of many of them from Poland in 1957, there seemed to be a chance. The Bund ran in the Knesset elections [of 1959], but did not get enough votes to get in. They really wanted to connect with the Israeli reality, but were aware of the situation.”

Artuski summed this up in an article in Lebns Fragn, in 1966: “We feel a permanent lack of intellectual forces in spokespersons, lecturers, journalists, suitable activists … We lack Hebrew-speaking members and also the financial means to operate among the youth, even though disappointment with and opposition to the Zionist parties is also widespread among the young generation.”

The impression is that the Israeli Bund was a closed club, correct in its analysis of certain phenomena, but irrelevant in terms of the new reality.

Torbiner: “Those people were indeed right and also mutually supportive, but relevant to Israel as well. When I made the film about Matzpen, I was astonished to discover that in 1963, its activists were writing critical articles about the Histadrut [labor federation] and about Israel’s isolation and its disastrous consequences. Well, you could find those things in Lebns Fragn already in the 1950s – for example, [people writing] that there will be no peace without a solution of the refugee problem, and [asking] ‘who can feel the tragedy of the problem better than we Jews?’ Or a 1967 article that says, ‘Holding on to the territories will not solve any problem. We will not achieve peace with the Arab states and we will not live tranquilly alongside the Arab states. We will be a country of occupiers and for that reason we will cease to be a democratic state.’ The Bund even supported the struggle of the Mizrahim [Jews of Middle Eastern and North African origin] in Wadi Salib in Haifa,” when residents of the slum district rioted in 1959.

Still, if these struggles were important to them – why did they write about them for a minority readership in Yiddish rather than in Hebrew, for the broad public?

Biran: “The use of Yiddish is often criticized. It is said to be a secret patronizing language of Ashkenazim, whereas Hebrew reflects equality in this country. But the opposite is true: Zionism suppressed all the languages here, in order to forge the ‘new Jew.'”

Torbiner: “People die, and so do languages. It’s a painful but natural process. The tragedy is the way it is happening in Israel. Zionism wanted to create a heroic Jew, and today we can see the result. He is an occupier, is violent and does not see the ‘Other.’ It’s the same with regard to Yiddish, the Palestinians and the Mizrahim.”

But does Yiddish without socialism interest you? Sholem Aleichem, for example?

Torbiner:

“These days Ghassan Kanafani” – a Palestinian writer who was assassinated by a car bomb in Beirut in 1972 – “interests me more than Sholem Aleichem.”

Opposition alternative

David Ben-Gurion did not mention the Bund when he said, famously, “without Herut and without Maki,” referring to his disdain for the right-wing Revisionists and the left-wing Communists in the Knesset – but disregard is more lethal than objection. The Bund, no less than Maki and Herut, was an opposition to Mapai-style Zionism. In some cases the Bund’s criticism resembles that of the Zionist left, as in this article by Yitzhak Luden in Lebns Fragn from May: “We can see clearly that Israel is drifting away from the path of democracy. Domestically it is being led on a neo-fascist road by the racist and McCarthyist laws of Yisrael Beiteinu, and externally it is being led into a political tsunami by Benjamin Netanyahu.”

But the Bund is not a Zionist organization and has remained outside the camp throughout its existence in Israel, because of its unwavering stance of being an alternative to Zionism. In Torbiner’s “Bundists,” the grandmothers and grandfathers, whose Yiddish accent ostensibly softens their image, are filled with sound and fury when they talk about capitalism and Zionism. “I am not a Zionist – far from it,” a declaration uttered by the radio announcer Michael Ben Avraham (Veinappel ) resonates through the film.

“From the Bund I learned the principle of ‘localness,'” Torbiner says. “I was born here, I am an Israeli and this is my place. Therefore I am fighting for its character.”

Biran, who like Shapira before him, is a former yeshiva student, adds, “The Bund offers a possibility of a different Jewish identity in terms of culture, secularity and equality which I have not found anywhere else. Identifying with it makes it possible for me to be a Jew without apologizing or bringing in God, and to be national without resorting to romanticized myths.”

The Bund alternative is not widely attractive because its ideas are complex: Most socialists are not interested in Yiddish, and Yiddishism is not a synonym for socialism. Perhaps this is why “Bundists.” hasn’t found an audience.

Torbiner: “I started making the film in 2006 and have barely just completed it. It was hard and suffocating, both because people don’t understand what I am talking about and because I got no significant funding. Even Channel 1 [state television], which is the natural and logical platform for this film, did not give it backing. I was enriched in terms of meeting special people – but became destitute.”

After a time, we returned, finally, to Kalischer Street and to the image of the solitary old synagogues in young Tel Aviv, and to the secularity of the 1980s and 1990s. Today some of the city’s synagogues are coming back to life, thanks to the movement of newly pious Tel Avivians. Maybe the Bund House will also be brought back to life by young people – of a different sort, of course.

In Torbiner’s film, Aharon Shapira states, “The Jewish people I knew is extinct, but the socialist idea will be resurgent and will triumph.” At the end of our conversation, he also quotes Isaac Bashevis Singer’s remark in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, that Yiddish has not yet uttered its last word. In regard to Israel and the socialism in it, Shapira holds out few hopes – as we saw, he has not been optimistic since 1945. Nevertheless, before we part it is important for him to articulate the whole Israeli-Bundist doctrine, and perhaps the most urgent message, in a nutshell, and he declares: “I only hope I live to see peace.” W