than any other – the Boycott. Terrorism,

suicide bombing, demagogy – holds no terror for the Israeli state compared with

the Boycott. Why? It can be summed up in a single word – ‘Delegitimisation’.

One of the many talking heads and policy wonks who are employed on Israel’s

behalf, Brigadier General (Ret.) Michael Herzog, a senior fellow of the Jewish

People Policy Institute explained:

‘What is delegitimization and what separates it from legitimate criticism?

At its heart, it is the rejection of Israel’s legitimacy as the nation-state of

the Jewish people. … This campaign usually begins with legitimate criticism,

which is then expanded to include the portrayal of Israel as an inherently

immoral entity due to its birth, essence, and character.

‘Israel is indeed strong, but it is

small and to a great extent dependent upon its international legitimacy. A

significant increase of its delgitimization may isolate it, erode its

deterrence and its freedom to act in its own defense, harm its economy, and

expose it to legal assault. The delegitimators hold before their eyes the image

of South Africa, which despite its military and economic might finally caved

under the accumulating pressure of years of sanctions and delegitimization. As

early as the 2001 Durban Conference, 1500 non-governmental organizations termed

Israel an “apartheid state” and called for its “complete isolation.”

…Don’t Underestimate the Delegitimization of Israel.’

Israel and Zionism’s defenders generously

inform us that we can oppose one or other of Israel’s policies, but if we connect

the dots and discern a pattern and as a consequence of that conclude that there

is something special and different about the Israeli state and the way it

defines itself as a Jewish state rather than a state of its own citizens, then

what we are doing is ‘anti-Semitic’.

|

| Skinheads in Sweden Confronted by anti-Fascists |

Of course the reality is that this is no more

anti-Semitic than opposition to Apartheid in South Africa was an example of

being ‘anti-White’ which some of the more stupid defenders of Afrikaanerdom

attempted. What Israel’s protagonists

are doing is to create a racial state based on religion as the signifier, the

marker that defines the borders and boundaries.

Those borders are, of course its indigenous population and a challenge

to that is a challenge to Israel’s ‘legitimacy’. Israel’s legitimacy includes the right to

dispossess the Palestinians in the name of its own identity, to expel them and

to deny them any political or civil rights.

There are, though, secondary

victims of this legitimacy. Firstly conversions to Judaism performed by Conservative

or Reform rabbis, or indeed Conservative or Reform Jews who are the children of

such converts, are not recognised by the Orthodox Rabbinate as Jews, though the

Israeli state recognises conversions performed outside Israel for the purpose

of the Law of Return, they cannot marry, divorce or be buried in a cemetery for

Jews controlled by the Orthodox Rabbinate . Jews in Israel who are not Jews according to

the halachic (the oral Jewish law as laid down in the Talmud) definition, i.e.

children of a Jewish mother, are in a mixed category of mixed race Jews. This is effectively the equivalent of the Nazi

‘mixed race’ (Mischlinge).

The question

of ‘Who is a Jew’ has become the eternal insoluble question for Israel’s

politicians and judiciary. It is as

impossible to answer as the question of who was an Aryan in Nazi Germany or a

White in South Africa (where there was a category of ‘honorary Whites’ for those

such as the Japanese). It is impossible

to define a ‘pure’ race when there is no scientific basis to race in the first

place, which is why in Germany, the definition of Aryan was in the negative,

i.e. not a Jew or a lesser racial

category, and the definition of who was a Jew rested on whether one’s

grandparents practiced Judaism in 1870.

To those who

doubt that Israel has attempted to create a new, racial category of Jew one

only needs to look at the identity card that every Israeli posseses. It has a category for citizen and separate

ones for nationality and religion. Many Jews

put down ‘none’ for religion but ‘Jew’ as nationality. Zionism’s aim was always to transform a

religious people into a nation/race. [Akiva Orr, The UnJewish State, Ithaca Press, 1983, p.100]

The

definition of Israel as a Jewish State is crucial to all of this.

It marks out those who will receive privileges such as access to leasing

most ‘national’ land (93% of the total Israeli land) and various other

benefits. The current March 2015 General

Election is being called around this question.

The Israeli Labour Party and much of the Zionist mainstream oppose

making this explicit but there is wall to wall consensus in the Zionist movement

behind the notion that Israel is a

Jewish state.

The racial

category of ‘Jew’ is not based on a biological definition but on the mythical construction

of the ‘Jewish people.’ Hence when it

comes to white Europeans or even Indian Jews then the Israeli Jewish race can

incorporate them, as tiers within the ‘Jewish people’. For example the Bnei Menaishe are a group of

around 5,000 Indians who claim to be ‘lost Jews’. Because they profess their devotion to the

Israeli state, despite the fact that their belief is a total myth, two thousand

have been brought to Israel. The Rabbis,

normally so vigilant when it comes to converting non-Jews, have issued the

necessary rulings and Israel’s Jewish population is in consequence enhanced. ‘Lost’Indian Jews come to Israel despite skepticism over ties to faith Ha’aretz

20.10.13

Boycott challenges the core legitimacy and

ultimately the identity of Israel and that is why it is feared. Not so much for its economic impact, which at

the present time is limited, but because of its political impact.

This is why a key part of the Zionist

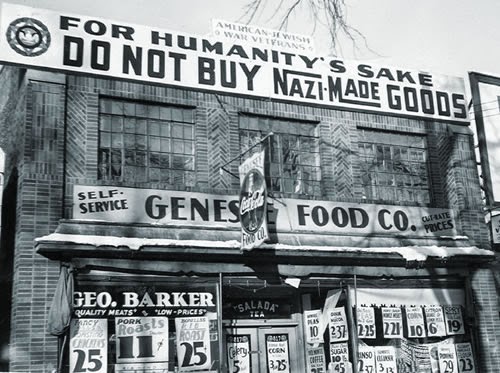

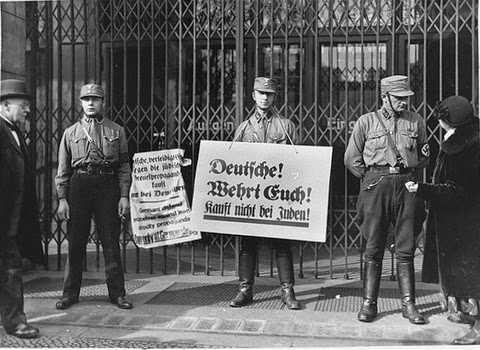

fightback is to label the Boycott of Israel as ‘anti-Semitic’. The comparison made is with the Nazi

so-called boycott of Jewish shops in Germany on 1st April 1933. In fact the SA

stormtroopers weren’t campaigning for a boycott of Jewish shops, they were

enforcing an armed siege of Jewish shops.

There was no element of persuasion as opposed to physical coercion in

what they did.

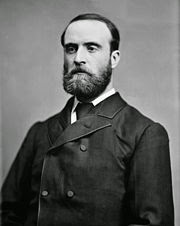

The Zionists, who always use the example of

the Nazi ‘boycott’ of Jewish shops never every make any mention of the

International Jewish Boycott of Nazi Germany because that would destroy their

case. It would also bring to the fore

the record of the Zionist movement itself during the Nazi era when they

concluded a trade agreement, Ha’avara with Nazi Germany, which broke the

International Boycott that could have removed Hitler from power. [see Edwin Black, Ha’avara – The Transfer Agreement,

Brookline Books, 1999] No less than 60%

of the capital investment in the Jewish Palestinian economy between 1933 and

1939 came from Nazi Germany [David

Rosenthall, Chaim Arlosoroff 65 Years After his Assassination, Jewish

Frontier, May-June 1998, p. 28, New York. http://www.ameinu.net/publicationfiles/Vol.LXV,No.3.pdf]

Below is a potted history of the Boycott movement, which demonstrates that

it was a vital non-violent movement in support of the oppressed – from Ireland

and the West Indies to South Africa and now Israel.

Tony Greenstein

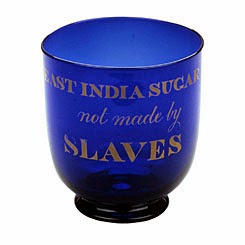

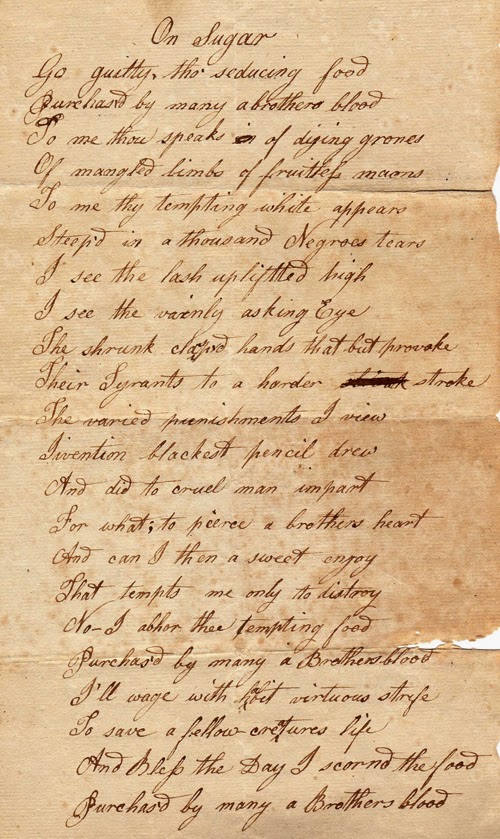

The Boycott of Slave Grown Sugar

“By

encouraging as much as possible the introduction of the products of free

labour, and refusing to use any articles which have been cultivated by slaves,

the women of Great Britain may do more for the suppression of the inhuman slave

trade, than all the ships of war that have ever ranged the coasts of

Africa…does not the price of every pound of slave-grown sugar, and of every

yard of slave-grown cotton, purchased for a British home, become a positive

premium on cruelty – a direct encouragement to those, who buy and sell human

beings – who tear the wife from the husband, and the child from the parent –

who steal the infant out of the cradle, and flog the mother with a cart-whip?”

(‘To the Women of Great Britain – on the Disuse of Slave Produce Pamphlet’, Birmingham

and West Bromwich Anti-Slavery Society, 1849, accessed via JSTOR)

|

| Tyler Family Papers – Poem on Slavery |

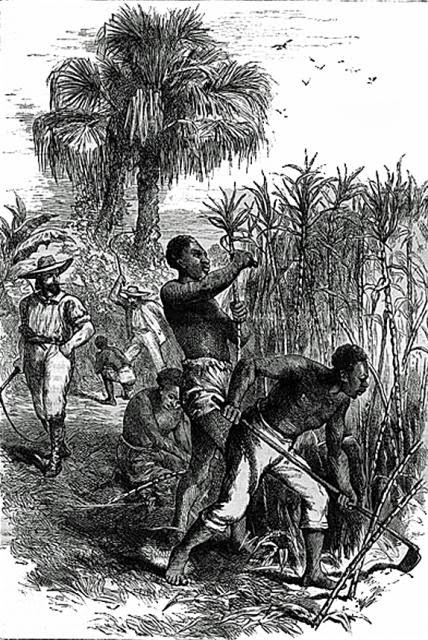

took action by sidestepping Parliament entirely and calling for

a boycott on Britain’s largest import, slave-grown

sugar. The Transatlantic Slave Trade flourished because a market existed for

produce created using enslaved labour:- rum, cotton, tobacco,

coffee and particularly sugar. The abolitionists understood that

profits from the sugar they used in tea or cakes kept the Slave Trade

running.

If economic pressure could be put on slave-dependent industries, then

this might hasten the end of the trade. An anti-sugar pamphlet

by William Fox was published in 1791; it ran to 25 editions and sold 70,000

copies in four months. Spurred on by pamphlets and posters, by 1792, about

400,000 people in Britain were boycotting slave-grown sugar. Some people

managed without, others used sugar from the East Indies, where it was produced by free labour.

|

| Silohouettes of Elizabeth Heyrick |

Grocers reported sugar sales dropping by over a third, in several parts of

the country, over just a few months. During a two-year period, the sale of

sugar from India increased ten-fold (see Adam Hochschild: Bury the chains).

James Wright, a Quaker and merchant of Haverhill, Suffolk, advertised in the

General Evening Post on March 6th, 1792, to his customers that he would no

longer be selling sugar. He declared:

“…..Being Impressed with a sense of the unparalleled suffering of

our fellow creatures, the African slaves in the West India Islands…..with an

apprehension, that while I am dealer in that article, which appears to be

principal support of the slave trade, I am encouraging slavery, I take this

method of informing my customer that I mean to discontinue selling the

article of sugar when I have disposed of the stock I have on hand, till I

can procure it through channels less contaminated, more unconnected with

slavery, less polluted with human blood……”

(A full copy of this article can be read here)

|

| Slave-grown sugar in the West Indies |

The boycott was revived in the 1820s, as the English movement pushed

for the total abolition of slavery in the British colonies. Abolitionists also

campaigned for people to stop purchasing at shops that sold sugar produced

using enslaved labour and some traders used notices

– similar to the fair trade notices of today – to let customers know that their

sugar did not involve slave-labour.

These campaigns were primarily supported by the female anti-slavery

associations, who distributed thousands of pamphlets and leaflets door-to-door,

in an effort to persuade British consumers not to buy West Indian sugar.

English ceramic manufacturers responded by making sugar bowls

and tea sets inscribed with anti-slavery slogans.

Although the effect may not have been crippling to the industry, it brought

together abolitionists in common cause and, at a time when only a small

fraction of the population could vote, citizens (particularly women) foundthe power to act when Parliament did not.

Quaker abolitionist Sarah Pugh in 1841, “need an abstinence baptism.”

Speaking at the third annual meeting of the American Free Produce Association,

Pugh claimed many abolitionists were stained by the “taint of slavery” through

their continued consumption of goods produced by slave labor.

abolitionists urged consumers to boycott slave-labor products such as sugar,

indigo, rice, and cotton. For Pugh and other like-minded abolitionists,

the boycott was about moral consistency: to be an abolitionist meant refusing

to benefit from slave labor. Still other abolitionists focused on the

enormous wealth vested in slaves and in slave-labor goods, arguing that a

boycott of slave-labor goods would strike at the economic root of African

slavery.

the Quaker reformation. The Seven Years’ War had led many colonial

Quakers to view the political crisis as a moral crisis caused by Friends’

continued support of slavery. Citing the golden rule, Quakers like John

Woolman now claimed slavery violated Christian principles of universal

brotherhood.

describing slaves and the proceeds of their labor as “prize goods” that had

been seized by force as an act of war. Slaves were captured and held for

the purpose of stealing their labor, all for the profit of their masters.

Both purchasing and using slave-labor goods, Woolman and other Quakers argued,

were contrary to Quaker precepts.

until the 1780s when abolitionists connected Britons’ dependence on slave-grown

sugar to debates about the international slave trade.

sugar 2.png

bill in the spring of 1791, abolitionists urged British consumers to join a

national boycott of slave-grown sugar. In support of the boycott, Baptist

printer William Fox wrote An Address to the People of Great Britain on the

Utility of Refraining from the Use of West India Sugar and Rum. Fox

calculated that if just one family consuming five pounds of sugar per week

abstained from sugar, that family could save the life of one slave.

produce nearly 130,000 copies of his pamphlet, which went through 26

editions. Another 120,000 copies were printed by other publishers in the

United States and Great Britain between 1791 and 1792, surpassing Thomas Paine’s

Rights of Man as the most widely distributed pamphlet of the eighteenth

century. In addition to Fox’s tract, dozens of other anti-slavery and

anti-sugar pamphlets were produced.

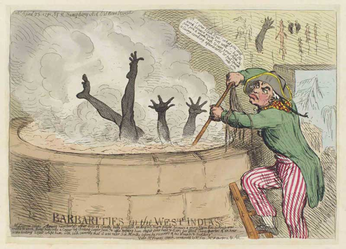

were among the most popular sites for consumption of slave-grown sugar.

The tea table was already viewed askance by many critics who saw it as a site

“for tea and scandal.” The table also represented privilege, leisure,

unchecked consumption, and gossip.

tables and reject sugar stained with “the blood of their fellow

creatures.” One writer claimed the physical conditions of colonial

slavery produced sugar contaminated not only by slaves’ blood but also sweat,

lice, and jiggers. In his print, “Barbarities in the West Indias,”

caricaturist James Gillray invoked the horror of cannibalism, suggesting that

slaves were boiled in pots of sugar cane juice. These graphic images were

intended to create a sense of disgust and revulsion in those who consumed

sugar. These appeals also played on what was seen as women’s innate sense

of compassion.

at the height of the boycott. By mid-1792, however, the boycott stalled as

the French Revolution turned violent. Horrified conservatives in Britain

distanced themselves from grassroots protests such as signing petitions and

boycotting sugar. Support for the boycott vanished.

abolish the international slave trade. Great Britain abolished the slave

trade in 1807; the United States abolished the trade in 1808.

products after 1808. New York Quaker Elias Hicks wrote Observations on

the Slavery of Africans and Their Descendants, and on the Use of the Produce of

Their Labour in 1811. Like Woolman sixty years earlier, Hicks

described slave-labor goods as “prize goods.” The produce of the slave’s

labor, according to Hicks, was “the highest grade of prize goods, next to his

person.”

momentum of the 1790s until 1824 when British Quaker Elizabeth Heyrick suggested

a more radical solution: the immediate, uncompensated abolition of

slavery. Removing the market for slave-labor goods, she argued, was the

first step in the immediate abolition of slavery.

In doing so, they challenged leading male abolitionists who continued to

support gradual, compensated (for slaveholders) abolition of slavery. But

when female abolitionists threatened to withhold financial support from the

national antislavery society, male abolitionists relented. In 1833,

Parliament passed the Emancipation Act, which was amended five years later,

ending the interim apprenticeship plan and granting slaves full freedom.

influenced by Heyrick, including Quaker abolitionists James and Lucretia Mott,

organized free-produce societies. In 1833 the American Anti-Slavery

Society and the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS) included

free-produce resolutions in their founding documents.

often failed to address the very real challenges of supply and variety which

confronted shop owners and consumers. Lydia White, for example, was a

member of the PFASS; her free-labor store in Philadelphia struggled to maintain

an attractive, steady supply of goods for customers.

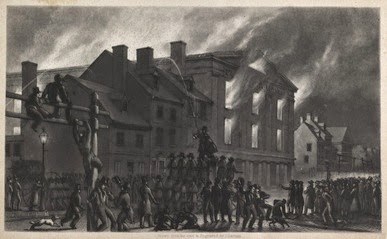

abolitionists organized the Requited Labor Convention in 1838. The

convention coincided with other abolitionist meetings, including the second

annual Anti-Slavery Convention of Women, in Philadelphia at the newly

constructed Pennsylvania Hall. Those meetings ended abruptly when

anti-abolitionist mobs burned the hall.

established the American Free Produce Association (AFPA), the first national

organization dedicated to the promotion and production of free-labor

goods. Along with the British India Society (BIS), established in 1839,

British and American abolitionists looked forward to increased production of

free-labor cotton, sugar, and other goods.

support. Prominent abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison criticized

the free-produce movement. Initially a supporter of the slave-labor

boycott, Garrison had come to believe the boycott was impossible to enforce and

a distraction from other, more practical tactics. In Britain, the BIS

lost political support and was absorbed into the Anti-Corn Law League. At

the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840, divisions among American and British

abolitionists who were quarreling over strategies and leadership eclipsed the

boycott.

continued through the American Civil War, retaining support from women,

Quakers, and black abolitionists. Boycotting slave labor was a radical

statement of abolitionist consistency and racial identification and the women

of the PFASS emphasized the morality of free produce.

goods while also focusing on the economics of the slave-labor boycott. In

an attempt to increase the supply and quality of free-labor goods, George W.

Taylor and other Quakers established the Free Produce Association of Friends of

Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1845. Taylor also operated a free-produce

store.

of slave and free labor. In 1850, for example, Henry Highland Garnet, an

African American abolitionist toured Great Britain, promoting free

produce. He also worked with American Quaker Benjamin Coates on a plan to

establish a free-labor colony in Africa.

asserted the importance of consistency in abolitionist work and the value of a

moral economy. That they continued to make these arguments in spite of

bitter criticism from even their fellow abolitionists is evidence of their

incredible resilience and their commitment to the slaves’ cause.

is Assistant Professor of Museum Studies at Baylor University, Waco,

Texas. http://www.ultimatehistoryproject.com/blood-stained-goods.html

|

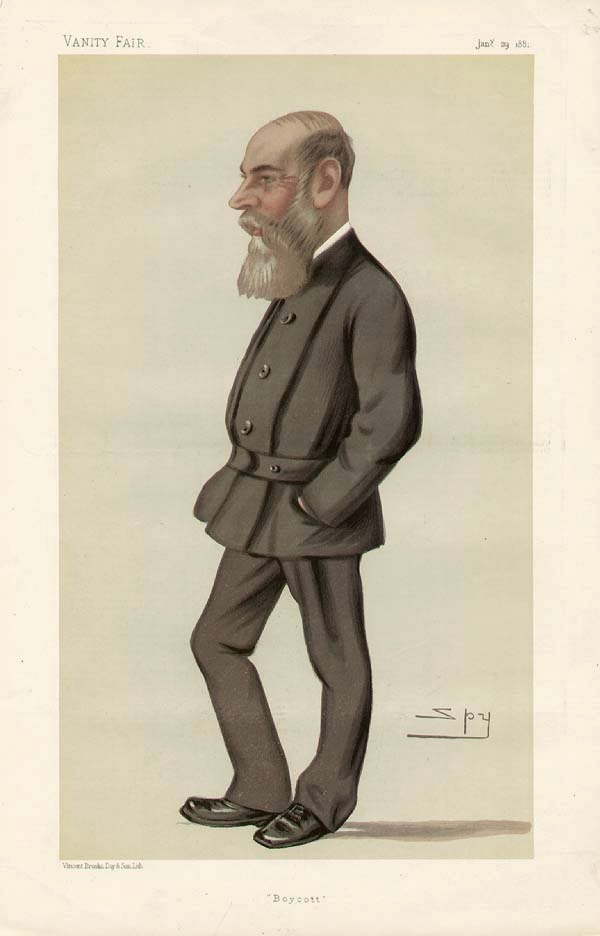

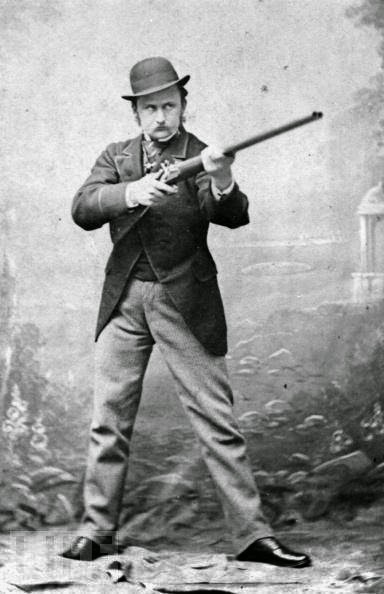

| Captain Boycott |

Northern Ireland of the 1880’s was

mostly owned by relatively rich landowners, many of whom were of English

descent and Protestants, while the land was worked by tenant farmers, mainly

Irish and Catholic. As predictably happens whenever one group controls

the assets and there are numerous asset-less workers, the tenants were

often exploited. In the 1870’s, there had been a depression, so farm prices

dropped, as well as a famine. Many farmers were unable to pay their rent.

estates in County Mayo in Northwest Ireland. His landlord’s agent was

Captain Charles Boycott. An Englishman, Boycott had a tenant farm

himself. As agent, his main job was collecting rent from Lord Erne’s

tenant farmers.

They felt their rent was too high; that they had no rights to improvements they

made to the land they worked. They felt the situation unfair, demanding

at the least a reduction in rent following years of low prices for their produce

and a lengthy famine. The Irish Land League was formed in 1879, campaigning for

the three F’s: Fair rent, Fixity of tenure, and Free sale. For the

next few years, the Land War ensued throughout Ireland.

refusing to pay rent unless the landlord agreed to a rent reduction. This

tactic succeeded in getting a 25% rent reduction from a Catholic Bishop in one

of the first protests. But Lord Erne was made of sterner stuff. He

refused his tenants’ demands for lower rent and had Boycott evict the

non-paying tenants.

turned violent; Irish revolts had been repeatedly crushed by England’s superior

force; agrarian violence in the Land War resulted in many deaths, harsher

criminal penalties, and eventually disbandment by force of the Irish Land

League. However, this time, the Irish adopted a new tactic.

Stuart Parnell, the Irish Land League President. gave a speech. During it,

Parnell asked: “What do you do with a tenant who bids for a farm from

which his neighbor has been evicted?” The crowd had some answers.

“Kill him,” “Shoot him,” “Refuse him whiskey!”

Parnell replied:

“I wish to point out to you a very much

better way – a more Christian and charitable

way, which will give the lost man an opportunity of repenting.

“When a man takes a farm from which

another has been evicted, Shun him in the streets of the town, you must

shun him in the shop, you must shun him in the fairgreen and in the

marketplace, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting

him in a moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of his country as if he

were the leper of old, you must show your detestation of the crime he has

committed”.

repeatedly failed. The new tactic—shunning, refusing to do business with

them at all—was first tried against Lord Erne and Captain Boycott.

Erne’s crops and isolated Boycott. People refused to speak to him; no one

would do business with him; washerwoman refused his laundry; the mail carrier

refused to deliver his mail. Boycott claimed the mail carrier—a mere

boy!—had been threatened with violence if mail service continued. Even

shop owners in a nearby village refused to serve him.

when the London Times published Captain Boycott’s letter complaining about his

situation. The English newspapers sent correspondents to Ireland.

The English papers viewed the situation as Irish Nationalists victimizing

a dutiful servant of a Peer of the Realm.

events, as supported by later witnesses, question whether the tenants’ actions

were violence free as Parnell’s speech urged. The sheriffs trying to

evict Lord Erne’s tenants, for example, swore they were pelted by stones and

dung. Thrown by women no less.

protestant Orangeman traveled to Lord Erne’s estate; to protect them, the crown

deployed an entire troop regiment and more than 1,000 Royal Irish Constabulary.

Approximately £10,000 was spent to harvest £500 worth of crops.

proved successful (depending on your point of view one must say) in at least a

few respects:

1880.

“boycott” not as a proper name but to describe a tactic of protest. The

verb “boycott” entered the English, Dutch, and other lexicons.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandh arrived in London to study law.

learn, eventually becoming a barrister. Ghandi refined the non-violent protest

technique of a “boycott” and used it extensively. It succoredIndia’s independence from the British Empire.

Famous personalities from the entertainment world have met in Hollywood in

order to sign a petition to President Roosevelt, which asks for the economic

boycott of Nazi Germany. From left to right: Melvyn Douglas, James Cagney, Edward

G. Robinson (seated), Gale Sondergaard, Mrs. Melvyn Douglas, Henry Fonda and

Gloria Stuart (standing).

to rush in and attack these men. Moments later, thousands of angry citizens

swarmed the men and chased them until they finally locked themselves in a

bathroom in a train station and had to be rescued by police. – See more at:

The Boycott of Nazi Germany

|

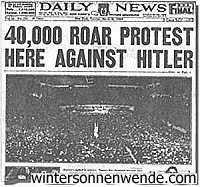

| mass rally in the United States against Hitler |

As soon as Hitler became Chancellor of Germany on January 30th

1939, world Jewry and the international

labour and trade union movement began organising a Boycott of Nazi Germany. The Germany economy was already in dire

straits.

leadership that on March 25th 1933 Goering summoned the leaders of the three

major German Jewish organisations Julius Brodnitz (CV), Max Naumann (Union of

National German Jews) and Heinrich Stahl (President, Berlin Jewish Community)

to a meeting. They were ordered to go to London and New York in order to put an

end to the stories about the persecution of Germany’s Jews and to have the

Boycott of German goods called off. [Black, p. 37,

The Transfer Agreement, Brooklyn Books, Massachusetts, 1999.]

The Zionist Federation of Germany (ZVfD) had not been invited to the

meeting because ‘Zionism in Germany was a

mere Jewish fringe movement.’ [Edwin Black, Ha’avara – The Transfer

Agreement, Brookline Books, London, 1999, p. 35.] The

ZVfD nonetheless found out about the meeting and managed to secure an

invitation for their President, Kurt Blumenfeld.

|

| The mammoth demonstration of 100,000 at Madison Square Gardens |

have a mammoth boycott rally in New York’s Madison Square Gardens on March 27th

called off. 55,000 would attend.[ Black, p.42]

The leaders of Germany’ Jewish community maintained that they were

helpless to prevent a boycott of Nazi Germany and that they had no influence

over Jewish actions in Great Britain or America. However

|

| SA Siege of Jewish Shops |

declaring that the German Zionist Federation was uniquely capable of conferring

with Jewish leaders in other countries… Once uttered, the words forever changed

the relationship between the Nazis and the Zionists. ‘ [Edwin Black, p.36.]

at the 25th March meeting, the Jewish and Zionist groups had feuded

but that the Zionists had agreed to use their influence to stop the newspaper

accounts of the atrocities and attacks on German Jews.[

Black, p. 52, citing minutes of the meeting of the German Cabinet of 29.3.33.]

|

| US Actors call for a Boycott of Nazi Germany including Edward G. Robinson, Henry Fonda, Gale Sondergaard, James Cagney, Melvyn Douglas, |

April 1st the International League Against Anti-Semitism declared a

permanent Boycott. On April 2nd

there was a mass protest by Jewish and Christian clergy. On April 3rd 70,000 Greek Jews

gathered in a mass protest and in Panama fifteen leading Jewish firms cancelled

all orders with Germany. On April 4th

there were Jewish protests in Bombay. In Upper Silesia, which Hitler later

annexed and where Auschwitz was situated, anti-German boycott violence was so

extensive that the German Foreign Ministry threatened to complain to the League

of Nations. In Britain the police in London and Manchester threatened to

prosecute storeowners displaying Boycott posters. [Black,

pp.104-5.] The Daily Herald

estimated that the fur boycott alone would cost Germany $100 million annually.

and Bnai Brith opposed a Boycott. On

March 19th their European equivalents held a conference in Paris

which decided that a Boycott was ‘not

only premature but likely to be useless and even harmful.’ [Black, p.12.] The Jewish bourgeoisie feared a Boycott more

than the Hitler regime.

there had been ‘an extraordinary slump

due to anti-Nazi trade reprisals.’ which the Munich Chamber of Commerce

confirmed on May 7. On May 8th

the German Economics Minister, Hjalmar Schacht threatened to stop paying

interest on American loans and then to default entirely on its foreign debt. [Edwin

Black, p. 116].

Foreign Minister von Neurath expressed concern over the boycott movement…. Clearly the boycott had

generated considerable fear in Berlin about its potential for severely

disrupting the government’s economic policies.’ [Nicosia, Zionism and

anti-Semitism in Nazi Germany, pp. 83-4. Cambridge University Press, 2008].

By mid-April England had supplanted

Germany as the largest exporter to Denmark and Norway. Sales to Finland were drastically down. Total German exports were 10% down in

April. For June the export surplus was

down by 68% compared to May. For the

entire first half of 1933 exports were down 51% and to other European countries

by at least 23%. Exports to France

decreased by 25%. ‘That six month loss would have been greater except that the

anti-Nazi boycott had not really commenced until late March.’ [Black, p.223.]

In Egypt the boycott was especially marked with a drop of $0.5 million

weekly. “Egypt was enforcing a virtually hermetic blockade.”They were also

down 22% to America compared with 1932 levels. [Black, pp.265,

273.] This was despite the Zionist and Jewish

leadership’s opposition.[ Black, p. 273 citing

NYT 1.8.33.]

disseminated atrocity propaganda faced the death penalty and began drawing the

obvious conclusion that the only way to stop the atrocity propaganda was to

stop the atrocities. [Black pp.223-4 citing US Ambassador

in Germany (Dodd) to Acting Secretary of State 28.7.33.]

travel were major foreign currency earners ‘but anti-Nazi boycotting virtually

bankrupted the industry.’ [Black, p.264.] Foreign endowments to German universities

declined by 95%. The wine industry, in

which Jews had been prominent, was also facing catastrophe. The directors of

the Dresden Bank resorted to asking for help from foreign banks. The Societe Generale replied pointing out

that Jews had been driven from their professions and that they preferred to trade elsewhere. [Black

pp. 264-6.] German banks were finding it difficult to

obtain even small loans from foreign banks ‘ authoritative opinion is that Hitlerism will come to a sanguinary end

before the New Year’ . [Black p.267 citing

Jewish Chronicle 11.8.33]

May 10th a massive demonstration was held, beginning in Madison

Square Gardens. [Holocaust Encyclopedia, http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/media_ph.php?MediaId=3549] Stephen Wise was the main speaker. Over

100,000 Jews and trade unionists took part.

In Britain, on July 20, despite the opposition of the Jewish

Establishment, the largest demonstration ever in support of a Boycott in

Britain took place, an estimated 50,000 people.

The Board of Deputies vehemently opposed a Boycott of Nazi Germany and

leading Zionist figures such as Herbert Samuel, former High Commissioner in

Palestine, heeded the pleas of the German Zionists to oppose the Boycott. In Britain, as in the USA, ‘the biggest obstacle to a united protest

and boycott movement was the coterie of leaders standing at the helm of the

Jewish community. [Black pp.62, 192].

supported the march. The TUC instructed

its affiliates and Co-operative societies to support the Boycott. [Black,

pp. 15,33, 180.] although

‘it became difficult to mobilise when

protest and boycott were incongruously disowned by Jewish leaders themselves.’

[Black, p. 208

citing Jewish Chronicle 28.7.33. ‘Our Leaders:

A Mockery of Democracy.’]

On 23rd July Neville Laski announced at the Board meeting

that he would, for the first time ever, be attending the next Zionist

Congress. The Jewish establishment had

committed itself to a Zionist solution of the German Jewish crisis. The Board voted 110-27 against the boycott

campaign. ‘This was a reprieve for the

Third Reich, a letup in the anti-German offensive…. (it) could not have come at a more decisive

moment.’ [Black

pp. 209, 210-213 citing Jewish Chronicle 28.7.33.]

Britain ‘raucous mass demonstrations

started in Manchester and swept through Newcastle, Leeds, Birmingham and

Glasgow. The protests culminated in an

overflow rally May 16 at London’s Queen Hall.’

When one Jewish shopkeeper was found with German stock, a thousand

angry protestors surrounded the store

and mounted police had to be called in. [Black, pp. 180,

184 citing Jewish Chronicle 26 May, 5th, 19th, 9th

June 1933, NYT 23, 28 July 1933.] Even the Archbishop of Liverpool urged

Catholics to join the Boycott!

held. The auction was a complete failure

as $3m of furs were withdrawn from sale. Such was the devastation facing their

industry that in June the fur industry was authorised to proclaim: ‘Jews in the

fur trade are welcome in Leipzig.’ [Black, p.181.] The

German diamond industry, which employed 5,000 workers, faced total collapse as

Antwerp’s mostly Jewish diamond merchants refused to deal with Germany. [Black, pp. 129-131, 181.]

already dangerously low. Germany simply

could not afford further export reductions.’ Without exports ‘there would be economic death.’[Black,

p. 24 Francis Nicosia, Germany and the

Palestine Question 1933-39, unpublished Ph. D.]

Jewish leaders went to New York and did their best to play down reports of

anti-Semitic violence. Despite their

leaders’ pusillanimity,

Germany’s Jews were doing all they could to bring the Nazi’s anti-Semitic

persecution to wider public attention.

some mere scraps of paper smuggled out of Germany – argued forcibly for the

truth. One eloquent message delivered to

Rabbi Wise said simply, “Do not believe the denials, Nor the Jewish denials.” [Stephen

Wise Challenging Years, the Autobiography

of Stephen Wise, Putnam, 1949, pp. 240-41.]

The

Boycott was extremely popular internationally.

It had been adopted by the labour movement in the United States. William Green, President of the American

Federation of Labor promised support which could, if it materialised, make the

Boycott almost completely effective. The

American Jewish masses were determined to go ahead with the Boycott campaign

regardless of the opposition of the Jewish and Zionist elite. [Black

pp. 43-4.] The Jewish War

Veterans on March 18th unanimously adopted a resolution supporting

Boycott. [NYT 22.3.33., 25.3.33., Jewish Chronicle

24.3.33.]

especially in Great Britain. Placards proclaiming BOYCOTT GERMAN GOODS spread

infectiously throughout London, and were now in the windows of the most

exclusive West End shops. [Edwin Black, p. 34.]

In Poland too, Boycott was popular and

the Jews of Vilna and Warsaw launched their own campaign. The Nazis were ‘astonished’, given the record of Polish

anti-Semitism, that the persecution of German Jews had given birth to a widely

supported Boycott movement. In Holland

and France similar movements were developing. During

May 1933 the Boycott movement spread further and wider. In Gibraltar one thousand Jewish merchants

vowed to boycott all German merchandise. The German Foreign Office was flooded

with letters from German firms expressing alarm over the intensity of

anti-German feelings abroad. [Nicosia, The Third

Reich & the Palestine Question,IB Tauris, London, 1985, p.36].

boycott. We have been and are doing all

in our power to allay agitation.’ [Black, pp.13,

63, citing NYT 31.3.33.] Yet Adler was in receipt of a letter of 3

April 1933 from a friend and German Jewish refugee, ‘Lionel’ in Paris detailing

the murders and atrocities against German Jews.

The letter pleaded with him ‘not

(to) take the slightest notice of assurances… whether they come from Jewish or

non-Jewish sources, from within Germany or from without.’ Germany’s Jews could not breathe a word of

support ‘because they would pay for such

information with their lives.’ He

called for a boycott of all German goods.

But Adler was unmoved.

in Palestine the Boycott was strongly supported ‘in spite of Zionist leadership.’

The German consul, Heinrich Wolff

warned that the momentum for a Boycott was growing. [Nicosia,

The Third Reich, p.38.]

However Wolff believed that Palestine was the key to destroying the

Boycott movement. [Nicosia, The Third Reich, p.41.] The Gestapo’s agent in Jerusalem wrote that ‘The London Boycott Conference was torpedoed

from Tel Aviv because the head of the Transfer in Palestine, in close contact with the consulate in

Jerusalem, sent cables to London [David Yisraeli,

‘The Third Reich and the Transfer Agreement,’ Journal of Contemporary History, vol. VI, 1971, p.132. Nicosia,

Zionism and anti-Semitism in Nazi Germany, p.109.]

the anti-Nazi movement, the Jewish press fell into line and became silent, not

least about atrocities committed against German Jews. In the first few days of April alone thousands

of orders for German goods in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem were cancelled. The ‘socialist’ Zionists of Mapai on the

other hand stepped up their campaign against Boycott on May 18th. On Kol Israel radio they proclaimed that ‘Screaming slogans calling for a boycott… are

a crime’ referring to a recent arson attack on the German consulate.

of Haim Arlosoroff on to destroy the Boycott. [Black, pp.122-3,

144, 159.] Arlosoroff, the Jewish

Agency’s unofficial Foreign Minister was the traitor behind Ha’avara, the Zionist-Nazi

trade agreement and because of this it was widely rumoured that he would be

assassinated. On June 16 the Revisionist

paper Hazit Haam issued what was

widely seen as a death threat. On the

very same day Arlosoroff was assassinated. [Black, pp.

151-153.]

US Administration were also keen to stop a Boycott, arguing that ‘Hitler now represents the element of

moderation in the Nazi Party’ and a Boycott Campaign would undermine his

position! [Black p.19.] The Administration had failed completely to

condemn the Nazi’s anti-Semitism. [Black p. 281.]

Hitler’s first Economics Minister and President of the Reichsbank, was

particularly concerned with the Boycott and when Julius Streicher suggested

that German firms dismiss their Jewish overseas representatives Schacht

explained the damage this was already causing to German trade pointing to how

Bosch had lost the whole of its South American market. [Hilberg,

p. 35, The Destruction of the European Jews, Quadrangle Books, Chicago, 2003].

9th June the German Zionist Federation [ZVfD], the Jewish Agency and

The Palestine Land Development Company began negotiations with the Nazi

government regarding Ha’avara (the Transfer Agreement). On August 10th 1933 agreement was reached.

[Edwin Black, pp. 249-50]. The 1933 Zionist Congress

didn’t dare approve it and waited until the 1935 Lucerne Congress. ‘Ha’avara

was a Zionist, that is, a Jewish, idea and initiative, not a Nazi one.’ [Nicosia

Anti-Semitism, p. 82]

were set up – Paltreu in Berlin overseen by the ZVfD and Ha’avara Ltd. in Tel

Aviv. German Jews deposited their money

in frozen marks (sperrmarks) in a

special account in Germany controlled by Paltreu. Ha’avara in Palestine placed orders for

German equipment and manufactures which were paid out of the frozen

account. Thus German exports increased,

paid for with German marks. Often little more than 20% of the proceeds was paid

to the immigrants whose money it was.

On August 31st the Nazis leaked the complete text of the

Transfer Agreement and the Decree of August 28th. [Black p.335] Pandemonium broke out and Berl Locker of the

Zionist Executive was forced into ‘lying

about the Executive’s involvement” and declared that ‘the executive of the ZO had nothing to do with the negotiations which

led to an agreement with the German government.’ [Lenni Brenner, Zionism in

the Age of the Dictators, Croom Helm, 1982, p. 64 citing Jewish Daily Bulletin,

29.8.33. p.4 see also Black pp. 314-5]

This pretence could not, however, be maintained for long. The Zionist Organisation was forced to

confirm its accuracy. The ZO declared

that the transfer agreement was the sole way of bringing into Palestine a

maximum of German Jewish capital. [Zionist Organisation defends Ha’avara, Jewish Chronicle,

13.12.35.] Zionist activists spoke of ‘saving the

wealth’ and ‘rescuing the capital from Nazi Germany.’ Black, pp. 257-258]

Following on from the Zionist Congress in Prague the 2nd

World Jewish Conference convened in Geneva from September 6th. Although it later became little more than an

appendage of the Zionist Organisation, at that time the WJC still retained a

measure of independence and its rank and file, who belonged to hundreds of

affiliated Jewish organisations, were overwhelmingly hostile to Ha’avara.

ally of Wise, supported Ha’avara in the debate of September 7th. He accused its opponents of playing into the

hands of the anti-Zionists! [Black, p.355.] The proposed

resolution called for the Boycott to be co-ordinated by a Central Jewish

Committee. But if that was the case,

then ‘a secondary boycott would

ultimately extend to the Zionist Organisation itself.’ [Black

p. 357.] Wise and Goldman took fright and when Wise

read out the resolution, the final sentence calling for enforcement via a

Central Jewish Committee, had been erased.

‘Wise, Goldmann, and the others on

the resolutions committee could not carry through. Not if it meant war with Zionism…’ The resolution’s enforcement was turned over

to the Paris-based Committee of Jewish Delegations, a Zionist body. ‘The

boycott would be led by leaders who in fact opposed it…. Wild applause erupted

as the audience cheered the emotional moment, never comprehending that it was

an ovation for failure.’ [Black, pp. 359-361.]

accounted for 60% of total capital investment in Jewish Palestine. [David

Rosenthall, Chaim Arlosoroff 65 Years After his Assassination, Jewish Frontier, May-June

1998, p. 28, New York. accessed 28.1.15].

In 1937 over 31m RM was transferred. [Nicosia,

The Third Reich, p.213.] Ha’avara

enabled over RM 100 million of German goods to be exported from Germany to the

Yishuv. [Nicosia, The Third Reich, p. 213, Hilberg fn9. p.

139.] In 1937 and 1938, as a

result of the Arab revolt, Jewish emigration to Palestine slowed down and

Ha’avara was no longer seen as effective. [Nicosia,

TRPQ p.212]. Ha’avara achieved the Nazis’ objective, which was that it ‘pierced

(d) a stake through the heart of the Jewish-led anti-Nazi boycott.’ [Black, p. 86.] ‘Without the world-wide effort to topple the

Third Reich, Hitler would have never agreed to the Transfer Agreement.’ [Black

pp.xxiii, 198].

throughout the Middle East and Cyprus, as the Palestinian market had become

saturated. The ZO set up the Near and

Middle East Commercial Company to sell Nazi Germany’s wares. Jewish Palestine had become Nazi Germany’s

export agents for the region. [Black p. 374.] After Krystalnacht the momentum was even

stronger for a Boycott campaign. Even

the American-German camp was no longer hostile.

Many companies lost 20-30% of their trade. ‘For

the first time the boycott movement gained many adherents among retailers,

distributors and importers.’ In

Holland one of the largest Dutch trading companies, Stockies en Zoonen in

Amsterdam, which represented Krupps, Ford and BMW ended all its contracts with

German companies. Only the Zionists

remained committed to trading with Nazi Germany. [Hilberg,

pp. 40-1.]

The Boycott was the only weapon with

which to prevent violence against Germany’s Jews and anti-Jewish

legislation. It ‘forced the Third Reich to vigilantly restrain anti-Jewish violence in

Germany since each incident helped intensify the anti-Nazi movement.’ [Black,

pp. 250, 372.]

April 1st 1933 the SA storm troopers organised a siege of Jewish

shops. The reaction of the representatives of the capitalists in the German

cabinet to the SA siege of Jewish shops was one of horror. Von Neurath, the Foreign Minister resigned,

retracting his resignation only after receiving assurances.[

Black p.59.] On 31st

March German stocks suffered badly with Die Trust falling 10% and Siemens

12%. This led Hitler eventually to agree

to a ‘pause’ in the SA siege of Jewish shops late on April 1st and a

‘brief moratorium’. The calling off of

the physical protests had been the achievement of the anti-Nazi Boycott

movement. [Black p.65.]

Executive in London admitted that the Boycott actions ‘have surely caused the

anti-Jewish boycott to be limited to one day’ [Black p.106]

whilst confessing that he and his friends ‘have attempted to energetically counter the so-called Gruelpropaganda [atrocity stories].’ [Black,

p. 106.] As Jacob Leschinsky

reported from Berlin, ‘The Hitler regime

flares up with anger because it has been forced through fear of foreign public

opinion to forego a mass slaughter.’[Black pp.12-13.]

Institutions, including Histadrut, the Manufacturer’s Association and other

Zionist groups, met to discuss how best to co-ordinate opposition to the

Boycott. ‘Breaking the boycott was the

only way to save the Jewish wealth of Germany.’ [Black pp. 130, 188, 191] Yet despite the sabotage of the Zionist

leadership popular Jewish support for a Boycott did not diminish. Goebbels at the annual NSDAP conference

described the boycott as ‘causing us much concern. It hangs over us like a cloud.’’ [Black

p.269.]

Berl Locker of Poalei Zion and Baruch Vladeck, editor of the Yiddish daily Forward and Chairman of the Jewish Labor

Committee, Vladeck described how ‘The whole organized labor movement and the

progressive world are waging a fight against Hitler through the boycott. The Transfer Agreement scabs on that fight.’ Vladeck

contended that ‘The main purpose of the

Transfer is not to rescue the Jews from Germany but to strengthen various

institutions in Palestine.’ Vladeck

termed Palestine ‘the official scab agent

against the boycott in the Near-East’ because ‘without the worldwide effort to topple the Third Reich, Hitler would

have never agreed to the Transfer Agreement.’ [Lenni Brenner, pp. 92-93, 51 Documents: Zionist Collaboration with the Nazis’, Barricade

Books, 1972.]

the Jewish Agency ‘saw their mission as obstructing anti-Nazi protest in

America and Europe, especially an economic boycott.’ [Black p.19.]

Deputies meeting, Dr Israel Feldman told of how

form of the products of German factories and German employment. We say that that is aiding and comforting one

of the most savage oppressions even in Jewish history… It is a distressing

reflection that into the Yishuv there flowed, last year, total imports from

Germany totalling about one and two-thirds million pounds…The boycott offered

Jews the first real weapon they have ever had… Ha’avara dashes that weapon from

their hands…. Ha’avara has actually exerted itself… to promote an increase of

the purchase of German products in Palestine.’

Germany survive once the Boycott became global…’ This was a reference to

Poland. The Investor’s Review reported

that ‘authoritative opinion is that

Hitlerism will come to a sanguinary end before the New Year.’ [Black, p.

266-267 citing ‘Hitler hard up’ Jewish Chronicle 11.8.33.]

safeguarded, stabilized and if necessary reinforced. Hence, the Nazi party and

the Zionist Organization shared a common stake in the recovery of Germany. If the Hitler economy fell, both sides would

be ruined.’ [Black, p. 253.] In return for signing the agreement the Zionists would halt the worldwide Jewish-led anti-Nazi

boycott that threatened to topple the Hitler regime in its first year…. The

leaders of Germany realized that the anti-Hitler boycott was threatening to

kill the Third Reich in its infancy, either through utter bankruptcy or by

promoting an imminent invasion of Germany…’ [Black pp.xix, 110, 130.]

the Third Reich.’ The Reichsbank had

only RM 280m in gold and foreign-exchange reserves, less than half that of

1932. In the first quarter of 1933

Germany’s export surplus was down from RM 94 million to RM 44 million. Edwin

Black asks whether Ha’avara ‘precluded

any chance of the anti-Nazi crusade succeeding.’ [Black, pp. xiii, 181-2.]

July 20 Lord Melchett and Samuel Untermeyer of the American League for the

Defense of Jewish Rights held the World Jewish Economic Conference to

co-ordinate the international Boycott.

Untermeyer was the only Jewish leader to vigorously advocate a

Boycott: ‘to millions of Jews and non-Jews alike, Untermeyer was the hero of the

hour.[

Black p.273.]

Stephen Wise, who became the most prominent Zionist leader

in the USA, was hostile. [Black p. 207 citing Jewish Chronicle 21

& 28 July 1933.]

Joining the Boycott now was ‘undesirable

and dangerous.’ People should wait

until the Second AJC on August 18th.

The WEJC slogan was ‘Germany will

crack this winter’.

returned to the United States on August 6th determined to quell

Wise’s opposition to the Boycott. ‘You cannot put out a fire… by just looking

on.’ He spoke of the 95% of WJC members who supported Boycott, apart that

is from the few timid souls who led them.

He called on the AJC’s ranks to ‘instruct

these false leaders in no uncertain terms as to the stand they must take… or

resign their offices.’ Untermeyer spoke of one particular leader, ‘the kingpin of mischief-makers’ whose

support for Boycott depends on the audience he is addressing. But on

August 14th, Wise was sufficiently stung by Untermeyer’s criticism

to declare his support for the Boycott when addressing the Prague Jewish

community. [Black, pp. 276-7]

two World Jewish Economic Conferences, rallies and demonstrations, the Boycott

was uncoordinated. But it was still

having a dramatic effect on the German economy as Jews, trade unionists and

many million others instinctively avoided purchasing German goods. This despite the lack of an activist

campaign, such as a refusal by dockers to handle German goods.

non-Jews were involved in the boycott and campaign, the Jews themselves were

taking advantage of the campaign to increase their profits and trade.

the Boycott of Israel with the Nazi Siege of Jewish shops (akin to Israel’s

siege of Gaza) on April 1st 1933. The

real comparison is with the Boycott of German goods. After the Nazi Party took office, eleven of

the world’s leading musicians, led by Toscanini and Fritz Reiner, announced a

boycott of German cultural events. [Black p. 61.] In Paris filmgoers cheered a band of Jewish

youth who disrupted a German film. The Nazi and Zionist responses to a Boycott

campaign was almost identical. Just as

the Zionist movement has threatened legal action against those who organise a

Boycott of Israel, so the German embassy in Latvia ‘sought court restraint for

Jewish student groups urging a boycott of German films.’ [Black, pp. 180, 183

citing Jewish Chronicle 5 May 1933 and NYT 11.6.33, 17.6.33].

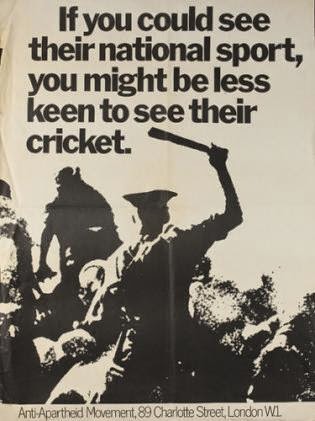

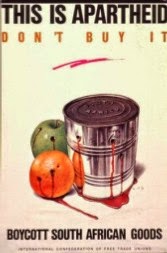

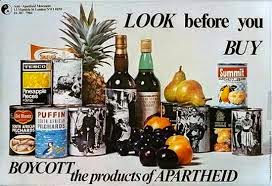

The Boycott of South African Apartheid

In June 1959, a small meeting took place in Finsbury Town Hall in London to mark South African Freedom Day and to launch the ‘Boycott Movement.’ Speakers included Julius Nyerere from Tanzania and Father Huddleston.

Early Beginnings

From such modest beginnings the AAM was formed. The first organisers set themselves the task of co-ordinating a month of boycott in March, 1960. Mobilising meetings and conferences were called and locally-based boycott committees set up across the country. The Labour and Liberal Parties gave their backing as did the Trade Union Congress (TUC) and the Co-operative Movement. The first council, the famous port city of Liverpool, came out in support of the campaign by itself deciding to boycott all South African goods.

It was an imaginative and effective campaign. The organisers were able to build on earlier efforts of solidarity with the freedom struggle in South Africa reaching back to Sol Platje’s visit to Britain in 1910 when he addressed literally hundreds of meetings across the country. But above all it provided a simple but effective way in which the growing revulsion in Britain to the tyranny of racial injustice in South Africa could express itself.

It was against the background of thousands of individuals and organisations actively campaigning for the boycott during the first month of action in March 1960 that the Sharpeville massacre occurred – to be followed shortly by the declaration of the state of emergency and the banning of the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan African Congress (PAC). The impact was immediate. It expressed itself in numerous protest actions both spontaneous and organised. It made Britain’s relations with South Africa a major domestic political issue where it has remained, despite ebbs and flows of interest, ever since. Most significantly of all it convinced those who had set up the Boycott Movement of the necessity for it to take on a permanent and comprehensive role as the AAM.

It is difficult to trace a history of 30 years’ in a few paragraphs especially given the tremendous variety and scope of the AAM’s campaigning activities. Although launched as the Boycott Movement it soon found itself shouldering a range of other campaigns. The most significant in those early days were the ‘Arms Embargo’ and the ‘Rivonia Trial.’ It was also during this early period that it looked beyond the borders of South Africa and began campaigning on the regional dimensions of the apartheid crisis. The pamphlet The Unholy Alliancemarked the start of campaigns against Portuguese colonialism and racist Rhodesia which became a more and more important element in the life of the AAM right up to Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980 and of course continue today with a very different content when we mobilise in solidarity with the Front Line States.

There have been many turning points over the past three decades, for instance the great rally in 1963 when the leader of the Labour Party, Harold Wilson, declared that a future Labour Government would impose an Arms Embargo against South Africa – only to be bitterly disappointed by Labour’s record in government on Southern Africa and in particular Rhodesia. There were the two International Conferences initiated by the AAM on sanctions in 1964 and Namibia in 1966. which demonstrated that the AAM was much more than a protest organisation in that it had a key role to play in de’ eloping international policy or Southern Africa.

There were the excitement and challenges as a result of the collapse of Portuguese colonialism in Africa and consequent independence for Mozambique and Angola in 1975. This fundamental shift in the balance of forces in the region created new prospects for the liberation struggle in Zimbabwe and Namibia, and in South Africa itself but also new campaigning tasks for the AAM as South Africa launched its policies of aggression and destabilisation against the Front Line States.

Hard Times

But, there were hard times too. Whilst the Soweto massacre of 1976 shocked public opinion, the AAM proved unable to arouse it in such a way as to compel any fundamental change in British policy. In the end, and only after the cold-blooded murder of Steve Biko and the banning of the South African Student Organisation (SASO) and other Black consciousness organisations did Britain finally agree to a mandatory Arms Embargo in November 1977 but then singularly failed to ensure that it was effectively implemented. Likewise as the struggle intensified in Zimbabwe it was never possible to generate such a powerful solidarity movement, either in Britain or internationally, that it could be a really decisive force on the side of the liberation movement. And the same can be said of Namibia in the sense that it took 11 years from the adoption of the United Nations plan for the independence of Namibia in 1978 to the beginning of its implementation. And then it started with the carnage of SWAPO guerrillas by South African forces operating under the authority of the United Nations.

By November, 1985 with South Africa increasingly ungovernable and support for sanctions reaching unprecedented levels up to 150,000 people tried to march on to Trafalgar Square for a huge rally addressed by Oliver Tambo and Jesse Jackson. And with the Thatcher administration as adamant as ever in its opposition to sanctions 250 000 gathered on Clapham Common in June 1986, within a fortnight of the publication of the Commonwealth Eminent Persons’ Group Report and the declaration of the state of emergency to demand sanctions at the huge AAM/Artists Against Apartheid Freedom Festival. And even these massive mobilisations were crowned by the ‘Nelson Mandela Freedom At 70’ campaign in 1988.

Sechaba, June 1989

Anti-Apartheid Movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), originally known as the Boycott Movement, was a British organization that was at the centre of the international movement opposing South Africa’s system of apartheid and supporting South Africa’s non-whites.

A consumer boycott organization

Expansion and renaming

Early successes

Commonwealth membership

Olympic participation

Abdul Minty, who took over from Rosalynde Ainslie as the AAM’s Hon. Secretary in 1962, also represented the South African Sports Association, a non-racial body set up in South Africa by Dennis Brutus. In the same year, he presented a letter to the International Olympic Committee meeting in Baden-Baden, Germany about racism in South African sports. The result was a ruling that suspended South Africa from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.[1] South Africa was finally expelled from the Olympics in 1970.

Economic sanctions campaign

In November 1962, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 1761, a non-binding resolution establishing the United Nations Special Committee against Apartheid and called for imposing economic and other sanctions on South Africa. All Western nations refused to join the committee as members. This boycott of a committee, the first such boycott, happened because it was created by the same General Assembly resolution that called for economic and other sanctions on South Africa, which at the time the West strongly opposed.

Making sanctions an election issue

Rejection by the West

Academic boycott campaign

Cooperation with the United Nations

Boycott Israeli Apartheid

|

| The Boycott that Israel and the Zionist movement fears |

If there’s one thing that the Zionists hate it is a description of Israel as an Apartheid state. Yet the evidence is very clear. It is true that Israel does not legally apply the petty apartheid of South Africa and Rhodesia (the ‘no Blacks or dogs’ posters) but the effect of Israeli Apartheid is no less pernicious.