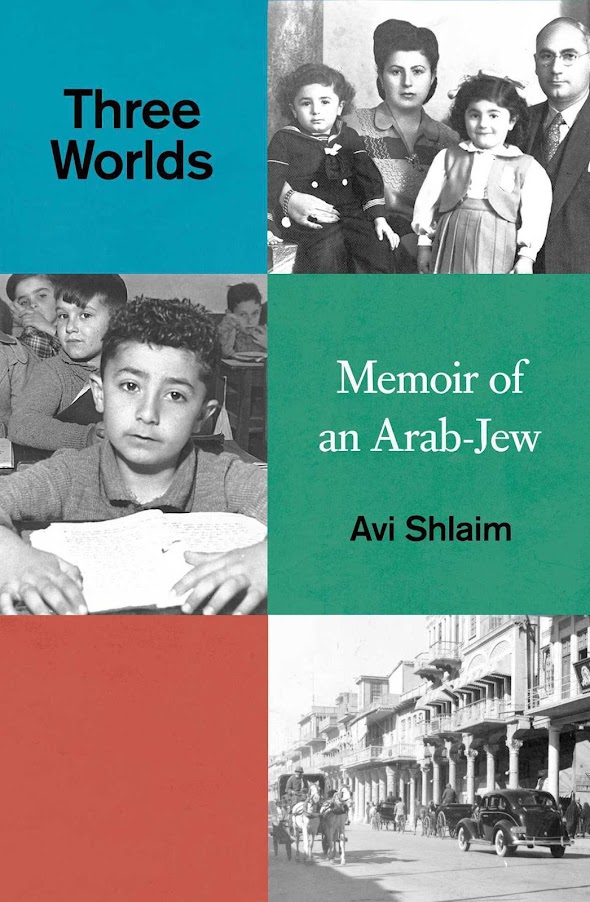

How Israel and Zionism Destroyed the World’s Oldest Jewish Community in Iraq

One World, London, 2023

Witness – The Last Jew of Babylon – 15 Jul 07 – Part 1

Avi Shlaim is Emeritus Professor of International Relations at St Anthony’s College, Oxford. He is also an Iraqi Jew who emigrated at the age of five to Israel before coming to England. It is a tale of 3 worlds – life in Iraq as an Arab Jew, in Israel as an alienated de-Arabised Jew and in England as a refugee from the Jewish ‘homeland.’ It is also, on a personal level, the story of how Zionism destroyed a Jewish community which was over 2,500 years old, in order to provide a working class for the ‘Jewish’ state to replace the Palestinian refugees.

Baruch Nadel, a journalist on Israel’s largest selling newspaper Yediot Aharanot, summed up the situation when he wrote that:

‘Zionism, not having saved the Jews of Europe found itself after the Second World War without a useful objective. To give a moral justification to the existence of their country, the Zionists looked for a way to “save” other Jews, regardless of their wishes. The only Jews with whom this would be possible were the Jews of the Arab world’. (Marion Woolfson, p. 198)

baruch nadel

The Jewish Chronicle’s idea of a review is a full-frontal attack with all the usual distortions!

The book is an intensely personal story that is symbolic of a far wider tragedy, the impact of Zionism on Iraq’s Jewish community.

Zionism was a movement that dedicated itself to one overriding goal since its founding at the end of the 19th century, the creation and perpetuation of a Jewish nation/race via the creation of a Jewish state. Shlaim describes how

We in the Jewish community had much more in common linguistically and culturally with our Iraq compatriots than with our European co-religionists. We did not feel any affinity with the Zionist movement and we experienced no inner impulse to abandon our homeland to go and live in Israel.

Witness – The Last Jew of Babylon – 15 Jul 07 – Part 2

Shlaim writes of how

Relations that were shaped over hundreds of years were erased in a few hours…. A history of more than 2,000 years is liquidated in less than 2,000 hours…. The interaction of two forces – Zionism and Arab nationalism – forced us to leave our homeland and transformed our lives beyond recognition.

This tragedy was personified in the figure of Shlaim’s father, Yusuf. A rich and prosperous merchant in Baghdad, on first name terms with the ruling elite, his Jewish identity was ethnic cultural not Zionist nationalist. In Israel Yusuf was reduced to poverty, jobless and living off his wife, Saida’s earnings as a telephonist in the town hall.

Avi Shlaim

Shlaim recalls when, in 1963, his Uncle Isaac, who was living in London, travelled to Israel. Isaac was ‘utterly shocked by the deterioration in the fortunes of the whole family’.

His mother, who had owned a luxury villa by the Tigris River in Baghdad, now lived in a tiny one-room bungalow in Ramat Gan. He remembered his uncles Jacob, Sha’ul and Joseph as prosperous merchants and men of considerable social stature in Baghdad. Now he saw for himself how drastically they had gone down in the world.

Zionism was not a ‘home-grown product but a foreign ideology propagated by emissaries from Palestine.’ Shlaim describes his mother’s ‘emphatic’ reaction when he asked her whether they had had any Zionist friends in Iraq: ‘No! Zionism is an Ashkenazi thing. It had nothing to do with us.’

When the Zionist Committee was given permission to function by the British, the local Jewish leaders met with the High Commissioner to express their opposition. ‘The Zionists were unable to enlist the support of any influential Jewish leaders.’

The largest, richest Jewish community in the Arab world, over 125,000, fled Iraq in the space of less than one year as five bombs (Naim Giladi in Ben Gurion’s Scandals says there were six) exploded in places frequented by Jews. It was the bombs which triggered the stampede.

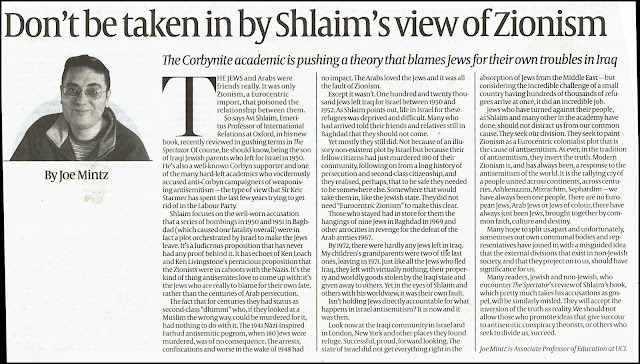

The Great Synagogue of Baghdad

On 21 July 1950, three months after the first bomb, the Shlaim family, except for his father who came over later, moved to Israel. The reason according to Saida, was that life had become too dangerous for Jews in Iraq and the bombs compounded this sense of insecurity.

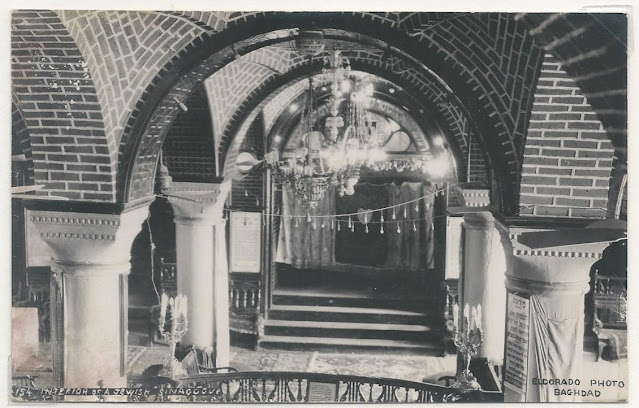

Shlaim describes Iraq’s Jews during the Ottoman era as the ‘most integrated into local society, the most Arabised in culture and the most prosperous.’ He describes his own childhood as ‘privileged and pampered.’ Among his parents’ friends was Jamal Baban, Minister of Justice and the wife of the Prime Minister, Tawfiq al-Suweidi.

By 1880 there were 55 synagogues in Baghdad. During the British occupation they controlled 75% of its imports. In 1935 the Baghdad Chamber of Commerce consisted of 9 Jews, 4 Muslims and 2 Britons.

By the end of 1951 all but 6,000 Jews had left in Operation Nehemiah and Ezra. When they arrived in Israel they were sprayed with DDT like animals as they got off the plane. Ben Gurion referred to them as ‘savage hordes’ and Foreign Minister Abba Eban remarked that

The goal must be to instil in them a Western spirit and not let them drag us into an unnatural Orient.

In October 1960 Ben Gurion declared that Jews in Muslim countries had ‘lived in a society that was backward, corrupt, uneducated and lacking in independence and self respect.’ He warned that ‘there is the danger that the coming generation may transform Israel into a Levantine state.’ This contemptuous racism towards Arab Jews later translated into victory for Menachem Begin’s Likud in 1977 and the eclipse of what had been Mapai (the Israeli Labor Party).

Iraq’s Jews were pauperised overnight. Bankers, lawyers and other professionals were reduced to begging for casual work. Saida described how, with the passage of time, Baghdad looked more and more like a ‘lost Eden.’

Iraqi Jewish refugees in a Ma’abara (transit camp), April 1951

Living at first in tents, they were dispersed mainly to development towns and collective settlements on the borders of Israel, there to guard against ‘infiltrators’ – Palestinian refugees trying to return. They had no say in where they went. It was the defence establishment which decided on the location of the collective settlements and development towns. Shlaim describes how

Books were kept with the names of those who left without permission and the lists were sent to labour exchanges to deny the escapees employment and housing. The police were asked to set up checkpoints and not to allow them to pass. Such draconian measures belied Israel’s claim to be a free and egalitarian society.

The Zionist movement saw a Jewish state in Palestine as a colonial outpost in the Middle East. In the words of the founder of Political Zionism, Theodor Herzl,

‘We should there form a portion of a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.’

theodor herzl

Zionism was founded on a contempt for the Jewish diaspora that rivalled that of the anti-Semites. Zionism began by accepting that Jews did not belong in the countries where they lived. It agreed with the anti-Semites that ‘exile’ had produced asocial characteristics in the Jews which in turn had led to anti-Semitism.

Zionism literally despised the Jewish Diaspora which it held responsible for all the ills Jews had suffered from, including the Holocaust. According to Jacob Klatzkin, the Jews were

a people disfigured in both body and soul – in a word, of a horror… some sort of outlandish creature… in any case, not a pure national type… some sort of oddity among the peoples going by the name of Jew

Such was the vehemence of these denunciation that Joachim Doron was moved to describe how:

rather than take up arms against the enemies of the Jews, Zionism attacked the ‘enemy within’, the Diaspora Jew himself and subjected him to a hail of criticism…. Indeed a perusal of Zionist sources reveals criticism so scathing that the generation that witnessed Auschwitz has difficulty comprehending them. [Journal of Israeli History 8, Classic Zionism].

joachim doron

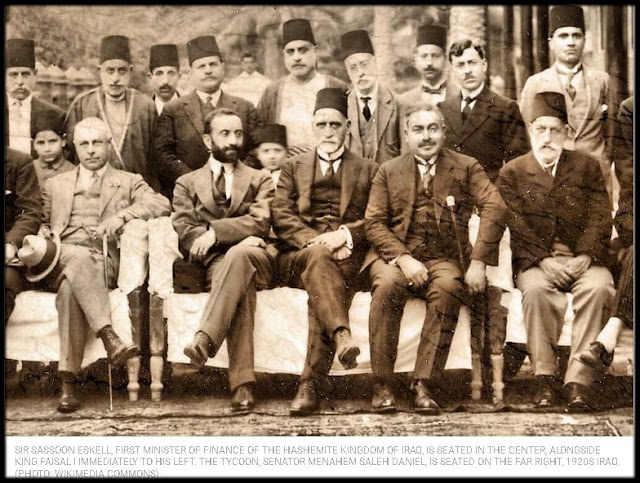

King Faisal I with Sir Sassoon Eskell, the Jewish first Minister of Finance, on an official tour of duty in Baghdad

The Ashkenazi leaders of Israel were determined that the Arab Jews must forget their roots and culture. They were to be shamed and made to forget where they had come from. Shlaim described how, if he was to identify one key factor that shaped his relationship to Israeli society, it would be an inferiority complex.

Shlaim describes how mortified he was as a child one day when his father approached him in a playground with other children and began talking to him in Arabic, forcing him to respond. Shlaim wrote that:

As an impressionable young boy I picked up and internalised the beliefs and biases of my new environment. I wanted to turn my back on my Arab heritage… Speaking Arabic did not sit well with the new identity I was adopting.

His sister Dalia refused to speak Arabic, even at home, ‘because she regarded it as the language of the despised Diaspora.’

The first lesson in the moulding of the Arab Jews was for them to discard Arabic. Hebrew was the language with which they would become acculturated and assimilated to Israel’s western-style culture. In the 1920s and 1930s a similar battle had been waged against Yiddish – another diaspora language. In the 1940s Ramat Gan became a battle ground in the country’s language war. A Yiddish language press was blown up by Hebrew language fanatics.

Shlaim describes how the sense of alienation he felt as a child translated into poor performance at school where he was shy and withdrawn, refusing to participate in and keeping silent.

I internalised the inferior status that I thought society had assigned to me and I behaved accordingly…. I felt out of place on account of being a Sephardi, an Oriental, a Jew from the East, a Mizrahi.

Shlaim describes one incident in his class where the teacher ordered him to remove his necklace and ring. Wearing jewellery, especially by men, did not accord with Zionism’s austere ideology. ‘It was a deeply humiliating experience… This was my equivalent of being sprayed with DDT.’ Yet despite this he passed his national exam.

Shlaim and many other Arab/Misrahi Jews faced the condescending racism of their Ashkenazi peers. Education Minister, Israeli Labor’s Zalman Aran, believed that poor performance in school reflected low native intelligence rather than external socio-economic factors. In 1959 Mizrahi children constituted 50% of their age group but only 18.8% of those attending academic secondary schools.

The curriculum was also Zionised. History was

more related to the project of nation building than to the disinterested pursuit of the truth…. The rich cultural heritage of the Arab-Jews was not just ignored, it was erased.

Jewish history was the history of Jewish suffering, what Salo Baron called the ‘lachrymose conception of Jewish history.’

At Israeli universities there is a department of history and a department of Jewish history devoted to rewriting history according to nationalist imperatives. At this time the Holocaust did not figure prominently and this situation pertained until the Eichmann trial.

Once the Holocaust became part of Israel’s war of propaganda then holocaust history too began to be rewritten to accord with the Zionist narrative. The heroism of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

was appropriated by Israeli propagandists to portray other Diaspora Jews as passive and weak in contrast to Israel’s ‘new-Jews.

As I show in Zionism During the Holocaust, the Zionist fighters in Warsaw fought despite the instructions of their own youth movements in Palestine to escape and come to Palestine. The real fight they were told was against the Arabs not the Nazis.

Yemenite immigrants gather for a photo at Rosh Ha’ayin

The 1950s was the era of Israeli Labor governments. During this time thousands of babies were stolen from Yemenite women to be given to Western Jews whilst the mothers were told that their babies had died.

Shlaim argues that anti-Semitism and anti-British feelings became intertwined as Iraq’s Jews were seen by Arab nationalists, as British agents.

On April 1 1941an anti-British coup by four senior army officers, the Golden Square, caused the royal family and regent Abdul Illah to flee to Transjordan. Rashid Ali al-Gaylani an ardent nationalist was appointed as Prime Minister and it was immediately decided to send an artillery force to lay siege to the RAF base in Habbaniya. Not until the end of May did the British regained control.

Immediately after, on June 1, as British soldiers waited at the gates of Baghdad, a pogrom broke out against Iraq’s Jews. Up to 189 were killed, hundreds injured and 10 women were raped. Shlaim suggests that keeping the troops outside Baghdad was ‘a fatal miscalculation’ but was it a miscalculation or something more sinister?

British historian Tony Rocca, in an investigation for the Sunday Times, found that Sir Kinahan Cornwallis, Britain’s ambassador, denied the Army’s requests to put down the anti-Jewish mobs and ‘while the Farhud raged, Cornwallis went back to his residence and played a game of bridge.” Marion Woolfson in Prophets in Babylon asked whether Cornwallis deliberately used the Jews of Baghdad as a foil for anti-British sentiment. Recounting ‘Farhud’ that ended 2,400 years of Iraqi Jewry

Shlaim describes how his mother, Saida, learnt that the British had deliberately not sent their troops into Baghdad and that

the secret motive of the British was to turn the Jews into scapegoats for the national humiliation that they themselves had inflicted on the Iraq army and the Iraqi people.

Yemenite Jews in camps

To the Zionists the Farhud is proof of the enmity of Iraq’s Arabs for their Jewish brethren. Yet it is a fact that hundreds of Jews were saved by their Moslem neighbours before troops were sent in by the Regent to clear the mobs. Shlaim quotes the case of one Muslim woman who stood in front of her neighbour’s gate with her Colonel husband’s loaded rifle, threatening to shoot anyone who came near them.

Compared to the horrendous massacres that were taking place in Europe at around the same time, when thousands of Jews were being killed in pogroms, what happened in Iraq was minor and one-off by comparison. Today Zionism has forgiven what happened in Europe since its main enemy is in the Middle East not Europe, with the neocon fiction about a ‘Judeo-Christian’ heritage.

To the Zionists this was proof that Arab society was anti-Semitic. According to the Zionist narrative ‘It was a turning point in the history of the Jews in Iraq.’ Yet if that is so, why did Iraq’s Jews take such ‘persuading’ to leave in 1950-1? Shlaim is clearly correct when he says that anti-Semitism was on the increase but that nonetheless ‘it was more of a foreign import than a home-grown product.’

Many Iraqis looked to the Nazis in the 30s and 40s because the Nazis were the enemy of their enemy, not because they supported Hitler’s doctrines of racial supremacy. Arabs too were Untermenschen. It was Britain not Germany that was occupying their country.

However anti-fascism was also strong among Iraqis. As Orit Bashkin observed, ‘during the years 1941-1952, most of the influential Iraqi intellectuals were identified with Socialist and Communist goals.’ It was the Left, that was ‘the most resolute opponent of Nazism and Fascism.’ [Iraqi Shadows, Iraqi Lights, Arab Responses to Fascism and Nazism, Ed. Israel Gershoni, 2014]

Shlaim says that it was ‘as supporters of the British that the Jews of Baghdad were murdered and looted.’ This is undoubtedly true but I have my doubts whether it was ‘an innocent celebration of a Jewish festival (which) became the spark for a barbaric pogrom.’ Shlaim says that the Jews were dressed up in their finery during the festival of Shavuot and that they were mistaken for celebrating the return of the British and royal family. Other reports suggest that a Jewish delegation had gone to the airport to welcome the Regent back.

Far from there being a pattern of attacks against Iraqi Jews, as the Zionists argue, there had been no such attack for centuries. The Iraqi Jewish leaders saw the Farhud as ‘an aberration’

In the wake of the Nakba and because a steady number of Jews were leaving Iraq illegally, the Iraqi parliament on 9 March 1950 passed a Denaturalisation Law which allowed Iraqi Jews to relinquish their citizenship and emigrate. At first very few Jews registered and even those who did were hedging their bets. On the first day after the law passed, just 3 people registered. But then the first bomb went off outside the American Cultural Centre and Library on March 19. Yet by April 7 just 126 Jews had registered. Then on April 8 a grenade was thrown at the Dar al-Bayda, a Jewish owned coffee shop. Four Jews were injured and the next day 3,400 Jews turned up to register.

It was widely suspected that the Israeli government had come to an agreement with Nuri e-Said that in exchange for Iraq’s Jews being allowed to emigrate, Iraq could keep their assets. An advocate of such an agreement was Mordechai ben Porat, the leader of the Iraqi Zionists and later a member of the Knesset.

By the end of 1950 90,000 Jews had registered to leave. On 14 January 1951 a hand grenade was thrown into the courtyard of the Masuda Shemtov synagogue. Three Jews were killed and 25 were injured. By the beginning of March 1951 105,400 Jews had registered to leave. But then Prime Minister Nuri e-Said introduced a law by which all Jewish assets were frozen and then confiscated and shops were closed and sealed by the police.

A couple more bombs were thrown at Jewish owned enterprises and by the end of 1951 over 120,000 Jews had registered to leave.

Chapter 7 Baghdad Bombshell, takes up the story that the Zionist movement in Iraq, decided to ‘encourage’ those Jews who were unwilling to emigrate to Israel of their own accord by exploding bombs in places Jews frequented. This was first broken by Haolem Hazeh andIsrael’s Black Panthers and then taken up by authors David Hirst, Marion Woolfson, Abbas Shiblak and Naim Giladi,

The Zionists have denied any role in the setting off of bombs in Baghdad but they have not explained why they were hiding caches of weapons that could have equipped an infantry company. As Israeli historian and journalist Tom Segev wrote:

It is significant the rumor arose at all, and that it was persistently repeated, even by Iraqi Jews. Obviously the idea was not unthinkable.’ [Tom Segev, The First Israelis’]

When Iraq hanged Yusuf Basri and Shalom Salih Shalom for having taken part in the bombing campaign, Israel mounted a campaign of support for them among Iraqi Jews. As a classified document to Foreign Minister Moshe Sharrett admitted, Iraqi immigrants in the transit camps greeted the hangings with the attitude ‘That is God’s revenge on the movement that brought us to such depths.’

It is indisputable that the bombs played a major part in the emigration of the Jewish community. The question is whether or not the Zionist underground played any part. Shlaim’s research suggests that 3 of the bombs were the work of the Zionists in the person of Yusuf Basri, who was arrested on 10 June 1951. Traces of TNT were found in his car. Basri’s controller was an Israeli intelligence agent, Max Binnet. In all 12 arms caches were uncovered.

Shlaim uncovered in the course of his research vital new evidence of Zionist involvement in the bombing campaign in the form of a new witness Yaacov Karkoukli, who served several prison sentences in Iraq for his involvement in Zionist activities.

Karkoukli was a fanatical Zionist who agreed with the bombing campaign and supplied new and important information as to who was responsible. Shlaim concludes that the bomb at the Dar al-Beyda on 8 April 1950 was carried out by the right-wing Iraqi nationalist party Istiqlal and the others by the Zionists or, in the case of the Masuda Shemtov bombing, at their instigation by bribing an Iraqi policeman, Salem al-Quraishi to have it carried out by one Salih al-Haidari’.

Shlaim asked Karkoukli whether that meant that Zionist activists had deliberately set off the bombs to which he replied in the affirmative. Karkoukli also confirmed that the Israeli government had given tacit consent to the confiscation of the property of Iraq’s Jews, mentioning that Israel intended to use this to offset claims by Palestinian refugees.

Shlaim also uncovered an Iraqi Police Report into the bombing obtaining one page of a 258 page document. Shlaim writes that

this report constitutes undeniable proof of Zionist involvement in the terrorist attacks that helped terminate the two and a half millennia of Jewish presence in Babylon.

The report pointed to the involvement of Zionist agents in the bombing, coupled with the fact that Zionist activist Yusef Basri led the Iraqi police from one arms cache to another.

The Zionist movement in Iraq had both opportunity, means and motive to carry out the bombing campaign. We know from the Lavon Affair shortly after, in which Israeli agents had been caught planting bombs in Egypt, that Israel had no compunction about committing terrorist acts in neighbouring countries. They did this despite the fact that it would inevitably rebound on Egypt’s large Jewish community and cause hostility and suspicion against them.

Zionism rewrote the history of Arab Jews so that the ‘Jewish’ state became the climax of their dreams, rescuing them from centuries of pogroms and discrimination. Accordingly the Arab Jews eagerly came to Israel in order to achieve their liberation.

This narrative is a post-facto self-serving justification. The Jews of the Arab world had lived in relative peace and harmony with their fellows. The Arab East had been a place of refuge for Jews fleeing from the Spanish Inquisition. Maimonedes, the greatest of Jewish philosophers, had sought refuge in Egypt as Saladdin’s personal physician. Jewish-Moslem relations in Spain had been harmonious in comparison with the Christian attacks on them.

To listen to Zionist and neocon propagandists you would be forgiven for thinking that the Holocaust had occurred in Arabia not Europe. That is why at the 2015 World Zionist Congress Netanyahu blamed the Mufti of Jerusalem for inspiring Hitler to perpetrate the Holocaust.

The story of how it was the Muslims who fought with the Jews against the Crusaders at the Battles of Hatin and Haifa and how Saladdin’s capture of Jerusalem enabled the Jews who had been expelled to return has been erased from Zionism’s historical memory. Even Zionist historian Bernard Lewis had to admit that ‘There is nothing in Islamic history to parallel the Spanish expulsion and Inquisition, the Russian pogroms, or the Nazi Holocaust.’

It has suited the needs of the Israeli state to rewrite the history of Arab relations with the Jews as one of enmity and persecution. However it wasn’t enmity between Jew and Arab that explains the Israeli-Arab conflict but the imposition by British colonialism of Zionism on the Middle East and Palestine. It is this that explains the deterioration of relations between Arab Jews and their non-Jewish neighbours.

Above all it was the expulsion of the Palestinians in 1948 and the defeat of the Arab armies that caused the deterioration in relations between Jew and Arab in the Arab countries. As a Jewish State Israel purported to represent Jews the world over, including those living in the Arab countries. Jews in many of these countries were singled out as a client intermediary group, creating suspicion and hostility..

Zionism made it impossible for Jewish communities to survive in the Arab world. Not only did Israel expel ¾ million Palestinians in 1948 but they did it in the name of all Jews. Not surprisingly many Iraqis questioned the loyalty of Iraq’s Jews. When UN Resolution 181 was passed in November 1947 the General Council of Iraq’s Jews sent the UN a telegram opposing the creation of a Jewish state.

Shlaim describes how a ‘powerful popular wave of hostility towards both Israel and the Jews living in their midst swept through the Arab world’ after the defeat and expulsion of the Palestinians. Britain’s unpopular ruler, Nuri e-Said, ‘actively whipped up popular hysteria and suspicion against the Jews.’ Zionism was outlawed and this marked the start of the official persecution of the Jews. Shlaim describes how his mother ‘singled out the birth of Israel as the decisive point in the crisis of Iraqi Jews.’

If Israel and the UK were at war imagine how Jews here would be treated. One only has to look at how the United States treated its Japanese citizens during WW2 after the attack on Pearl Harbour to understand that the hostility between Israel and the Arab countries was bound to impact adversely on the Jews of those countries.

The final part of the book concerns the decision of his mother to send her son to England to continue his education. On 7 September 1961 Shlaim set sail from Haifa to Marseilles and he was accepted as a pupil at the Jewish Free School in London.

It was now that Shlaim began to blossom academically. He describes how ‘considerable glamour and kudos’ attached at that time to being an Israeli yet because he was an ‘Israeli of the wrong kind’ he was left in something of a quandary as his different identities collided.

Shlaim described how Jewish history that was taught at JFS focussed on persecution and martyrdom whereas Israeli history emphasised heroism and redemption: ‘the history we were taught at school was scarcely distinguishable from Zionist propaganda.’ One suspects that the same curriculum is still being followed today.

Shlaim concludes from the experiences of his family that

there was another category of victims of the Zionist project: the Jews of the Arab lands…. Unlike Europe Iraq did not have a ‘Jewish problem’…. Zionism changed all that. By endowing Judaism with a territorial dimension… it accentuated the difference between Jews and Muslims in Arab spaces… Zionism not only turned the Palestinians into refugees; it turned the Jews of the East into strangers in their own land. In 1947-49 it was not only the land of Palestine that was partitioned but also the past.

Shlaim who is now a supporter of a one democratic state solution notes how this would also renew the relevance of the Arab Jew. In his concluding remarks Shlaim notes how ‘apartheid in the twenty-first century is simply not sustainable.’

If I have one criticism of this book it is that we need a Dramatis Personae of all the friends and family who make an appearance. At times I found it difficult to follow the many different stories.

Tony Greenstein