camp. However this piece provides insight into the unique savagery of the barbarities of fascism and its factories of death.

|

| Birkenau-Auschwitz in January 1945 after the Soviets had captured it |

Auschwitz wasn’t officially known of as

an extermination or death camp, as opposed to a concentration camp, until April

1944 with the writing of the Auschwitz Protocols. However British Intelligence was aware of the

activities of Auschwitz far earlier owing to decryption of Nazi signals. At Bletchley Park, the SS code had

been broken early in the war including communications with the extermination

camps. During the summer of 1941 Order

Police reports of mass shootings in Occupied Russia were deciphered.

Terrible Secret shows, there was no interest, either by the West or the Zionists

in uncovering the secret of Auschwitz. That was why it remained undiscovered.

We should not be deterred from understanding what happened in the Holocaust and why, simply because today the Zionist movement, the Israeli state and the Western capitalist states exploit what happened over 70 years ago in order to justify Israel’s racist obscenities. Zionism, with its creation of a state based on race, defames the memory of those who died, Jewish and non-Jewish, in Auschwitz and Birkenau. That however is never a reason to deny that the Holocaust took place. The Zionists create holocaust denial through their exploitation of the memory of the millions who died. Indeed they deliberately create the false ideology of holocaust denial in order to ‘prove’ that the anti-Semitism which they create is still alive.

|

| The famous and cynical slogan ‘Work Makes You Free’ which was above Nazi concentration camps – the same idea was adopted by Ian Duncan Smith when cutting social security benefits in Britain |

extensive and there may, at first, seem to be little point in publishing yet

another memoir of one of its former inmates, all the more so when the memoir is

brief and adds no new facts to those already well-known to the world. But it is

the person and perspective of the author which give the memoir below some claim

to our attention. The author was the Ukrainian Marxist Roman Rosdolsky

(1898-1967), who was arrested by the Gestapo in Cracow in 1942 for aiding Jews.

Rosdolsky had been one of the founders and leading theoreticians of the

Communist Party of Western Ukraine, but he left the party in opposition to

Stalinism in the late 1920s. He remained true to the principles of

revolutionary Marxism for the rest of his life. Since the 1930s he devoted

himself to scholarship, producing a number of important studies in German and

Polish on the agrarian history of East Central Europe and on the history and

interpretation of Marxism. Part of the latter series was his very famous work

on The Making of Marx’s Capital (Pluto Press, 1981).

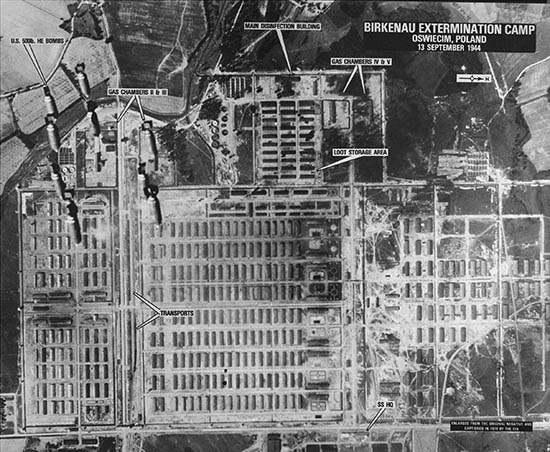

|

| Aerial reconnaissance of Birkenau |

originally published in the Ukrainian emigre socialist journal Oborona in 1956

and reprinted by another Ukrainian socialist journal, Diialoh, in 1984. This is

its first appearance in translation.

History, University of Alberta).

“death museum at Auschwitz” in your periodical. Permit me to use the

occasion of your remarks to share with Oborona’s readers some memoirs

concerning my own stay in the camp at Auschwitz.

you paraphrase was mistaken only in one point: Auschwitz was not only a

“death camp” but also an enormous forced-labor camp, with numerous

subsidiary camps spread over considerable territory; on the average it held

some 80,000 slaves of the German Reich. It was a sui generis “state within

a state,” with a whole series of industrial, mining, and even agricultural

enterprises. Its goal was to extract as much labor as possible from the

prisoners working there, while spending as little as possible on feeding them.

In this sense the entire camp was also an enormous “death factory” in

which–especially in its first years of existence (1940-42)–the average

prisoner did not remain alive longer than three or four months.

Auschwitz until early 1943, that is, at the time when the regime in the central

camp, Auschwitz proper, where there were 15,000 prisoners on the average, had

begun to relax. This relaxation was shown, above all, in that after May of 1943

the so-called Kapos, Blockaltester, and Stubendienste no longer had the right

to kill with impunity prisoners subordinate to them; before then, such murders

were everyday business. The Kapos, etc., were prisoners, generally professional

criminals, appointed by the camp authorities to head work teams and keep charge

over the barracks in which we lived. This “reform” was mainly motivated

by the labor shortage which the Third Reich was beginning to feel; the

Hitlerites decided to “economize” on human material that was still

fit to work. True, even in the first months of 1943 they still sent all

cripples, old people, typhus convalescents, and people with swollen legs or no

teeth to the crematorium. I myself was in the camp “hospital” and

lived through two large-scale “sortings” in which Hitlerite doctors

combed through the patients, sending several hundred to the gas chamber. But by

the middle of 1943 this particular horror had passed for us, i.e., for the

so-called Aryans (non-Jews), and we could report sick and go to the hospital

without risking death. To the unfortunate Jews, however, and only to them, this

reform did not apply. Still, some months later, we witnessed a horrific

spectacle as a dozen or so trucks pulled into the camp and took hundreds of

people from the hospital, clad only in their shirts, to the gas chamber.

|

| women huddled in their bunk after Auschwitz had been captured |

Auschwitz, which–I repeat–during 1943-44 began to become more and more like

ordinary Nazi labor camps such as Dachau, Oranienburg, and Buchenwald. But

three kilometers from us was a huge subsidiary camp, Birkenau (in Polish:

Brzezinki), where living and working conditions were a hundred percent worse

than our own; it had gas chambers and six crematoria in which people were

killed with poison gas and the corpses burned day and night. Here the gates of

Hitler’s hell were thrown wide open.

|

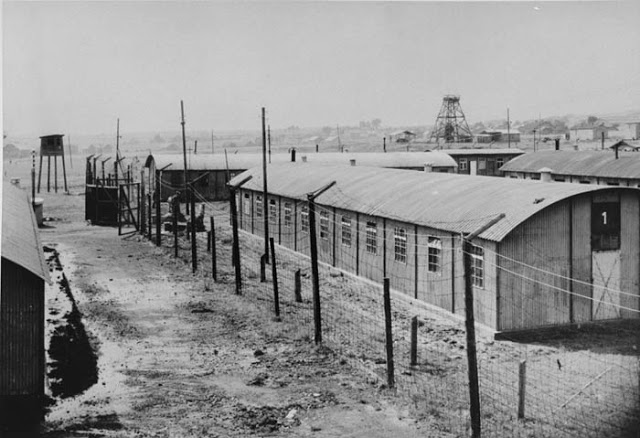

| Trzebinia sub-camp of Auschwitz |

Birkenau had “finished off” 16,000 select Soviet POWs: Red Army

officers, politruki, Communists, intellectuals. Of that entire transport only

fifty persons survived. Here, too, several dozen thousand

“recalcitrant” Poles met their Golgotha. And this was a gigantic

cemetery for the Jewish population of almost all of continental Europe.

1944, transports would arrive at Birkenau with thousands of Jews from Poland,

Slovakia, Bohemia, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Greece. Only a

small portion of them–specialists of all sorts–were chosen to work in our

camp and Birkenau. The rest, and all women and children, were immediately

dispatched to the gas. It was such an everyday occurrence and we grew so

accustomed to it that we began to note as extraordinary those days when there

were no Jewish transports and no flames shot up from the chimneys of the

crematoria.

this. Unfortunately, not just from conversations with other prisoners in

Auschwitz and Birkenau; I was forced to witness it. From spring 1943 until

autumn 1944 I worked as a carpenter on the second floor of a huge factory,

Deutsche Ausrustungswerke, which stood halfway between the main camp and

Birkenau. The large factory windows looked out over Birkenau. From them we saw,

maybe a hundred paces from us, the end of the railroad tracks leading to

Birkenau as well as, and above all, the chimneys of the crematoria. We could

have no doubt about what went on beyond the gates of Birkenau’s hell. There’s no

point in going into all we experienced and how we grew old inside during that

year and a half. I’ll just describe the most terrible period, the so-called

“Hungarian action” of the summer of 1944.

in, day out thereafter, four or five long trainloads of Hungarian Jews would

pull into the tracks before our windows. They were unloaded in a hurry, and any

bundles anyone had were taken away. Then SS-men came and divided the new

arrivals into two groups, separating the men from the women and children. They

chased them all off to the “showers,” that is, to the gas chambers.

Immediately afterwards a special work team went through the bundles, removing

food and clothing and searching for money and gold. The barracks of this work team

were separated from our factory only by a wooden fence. The team was made up of

several dozen young women prisoners, each wearing a red kerchief on her head.

They were allowed to eat whatever perishable food they found in the bundles.

This dreadful work team was generally referred to as “Canada.”

“Canada’s” yard was already piled high with bundles. We were always

tormented by hunger, and the bolder prisoners among us began to steal these

bundles from behind the fence. At the same time the smoke began to billow from

all six crematoria. And this was not all. Just next to Birkenau, to the right

of us, lay a birch forest (hence the name Brzezinki/Birkenau). A huge fire

began to blaze in the woods, the flames alternating with thick, yellowish-grey

smoke. A few days later we found out what was happening: the crematoria were

unable to handle thousands of corpses, so a deep pit was dug in the Birkenau

woods to burn the unfortunate victims. Some time at the end of May our factory

received an order to supply Birkenau with a dozen or so iron-tipped hooks four

meters long. At the head of the order, which I read with my own eyes, it said:

Ungarische Aktion.

“iron curtain” they design and produce bombs that can destroy and

pulverize just as many living people in the span of one minute. But the Third

Reich did not yet know the blessings of modern technology.

life of our work team? Imagine: rows of work tables, at which stand our

carpenters, sad as can be and “blacker than the black earth”–mainly

French Jews and Poles. No one speaks. All eyes are focused on the woods of

Birkenau and the crematoria. Only now and again someone laughs bitterly,

hysterically, and then wipes tears from his cheeks. It was impossible to open

the window, since the air was completely permeated by the intolerable, stifling

odor of burnt flesh. “Ich rieche, rieche Menschenfleisch (I smell, I smell

human flesh),” my friend Ludwig, an Austrian, tells me, using the words of

a witch from one of Grimm’s fairy tales. Only the witch smelled in the air the

scent of two children, and we smelled the odor of burned corpses, thousands of

corpses.

astonishingly tough. Day after day we went to our factory, stared at the bloody

incandescence of the Birkenau woods, and none of us went insane, none of us

took our own lives. Yet could we have entertained any hope of evading death in

the gas chamber? After all, we were witnesses to one of the greatest crimes in

human history! One of our carpenters said to me: “Today it’s them [the

Hungarian Jews], tomorrow it’s us [the Jewish specialists in the camp], and the

day after it’s you [all the non-Jews].” And this resolution of the matter

struck us all as the only rational one from the Hitlerites’ standpoint, the

only possible one. How else to be rid of the witnesses to their crime? Only one

faint hope flickered in some of our hearts: that the collapse of the Third

Reich would catch those beasts by surprise before they could accomplish their

plans and that at the last minute fear of retribution would stay their hands.

But during the entire month of August, we ourselves had to dig a great pit in

the central camp, just like the one that had been dug in the Birkenau woods.

Officially it was called a Luftschutzkeller (air-raid cellar), but there was

not one prisoner in the whole camp who was fooled by this name.

came to an end unexpectedly. In the first days of September I was included in a

transport of Polish and Soviet prisoners being sent from Auschwitz to

Ravensbruck, near Berlin. When they herded us into the wagons, we still kept

thinking that they were going to transport us to Birkenau, to the gas chambers.

But our train moved west and the glow from the crematoria disappeared from

sight. We began to breathe fresh, unpoisoned air. And though we knew that death

lies in wait for all prisoners in Hitler’s camps, we were none the less as

happy as children, because we had been snatched from the hell of Auschwitz.

old wounds? Let me just recall one small episode. It was in the camp, on

Sunday, after lunch. A group of prisoners were lying on their bunks and talking

about the end of the war, which they expected was approaching. A young Pole,

Kazik, turned to an older prisoner, whom everyone called “the

professor,” and asked him: “Professor, what will happen to Auschwitz

after the war?”

professor,” said Kazik. “No one here will get out alive.”

professor. “But, still, the living should not abandon hope [words of the

Polish poet Juliusz Stowacki]! And as for Auschwitz itself, the new Poland will

build a great museum here and for years delegations from all of Europe will

visit it. On every stone, on every path, they’ll lay a wreath: because each

inch of this earth is soaked with blood. And later, when the barracks collapse,

when the roads are overgrown with grass and when they have forgotten about us,

there will be new and even worse wars, and even worse bestialities. Because

humanity stands before two possibilities: either it comes up with a better

social order or it perishes in barbarism and cannibalism.”

repeating the words already spoken by the socialist thinker Friedrich Engels 80

years ago. I had heard them several times before the war. But in the bunks of

Auschwitz they sounded more real and more correct than ever in the past. And

who today, after all the Auschwitzes, Kolymas, and atom bombs, can doubt the

truth of these words?

of Auschwitz and Birkenau.” Monthly Review, Jan. 1988, p. 33+. Academic

OneFile,

go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do? Accessed 12 Apr. 2017.