70 years ago, the Nazis launched their infamous pogrom against the Jews of Germany, killing dozens of people and burning hundreds of synagogues and smashing the glass of Jewish shops. Contrary to myth, this was not at all popular among ordinary Germans or even the more middle-class elements of the Nazi Party.

Even Herman Goering was angry at this SA organised pogrom since it was German insurance companies who picked up the bill! Goering imposed a ‘fine’ of 1 Billion Reichmarks on the Jewish community. The pretext for Krystalnacht was the assasination in Paris of Ernst vom Rath, an official at the German Embassy (ironically he was anti-Nazi) by Herschel Grynszpan, a Jewish youth who had fled to France from Germany (& was later captured in the invasion of France but may well have lived out the war). He killed vom Rath in revenge for the treatment of his parents and many other Ost Juden who had been deported or rather dumped over the Polish border.

One of the persistent arguments of anti-Semites who purport to support the Palestinians, is that any mention of the Nazi holocaust is playing into the hands of the Zionists. As Gilad Atzmon wrote to me on 23.6.2005:

‘I do not have any doubt that our notion of the H will change radically in the near future. Too many discrepancies. and as I said, the only active scholarship is in the hands of the revisionists. The funny bit is that only left Jews are defending the Zio-Anglo-American’s H narrative.’

Note the ‘Zio-Anglo-American’s H narrative’ i.e the extermination of millions of Jews and millions of others too. But this is a ‘narrative’ which, according to Atzmon can only benefit the Zionists and it is ‘only left Jews’ who tell it apparently! And of course if the only active scholarship is by revisionists and there are ‘too many discrepancies’ [Atzmon being an expert in these matters!] then the conclusion is obvious. Maybe there was no Holocaust.

I mention this because Canon Paul Ostreicher, whose record on anti-racism – in support of refugees, against Apartheid and with Amnesty International – is second to none. He wrote an excellent article for the Guardian on November 4th which drew all the right parallels between Zionist attitudes to Palestinians and Nazi attitudes to the Jews. Following on from the predictable Zionist attacks, I wrote a letter which was published in the Guardian today.

Tony Greenstein

guardian.co.uk,

Tuesday November 4

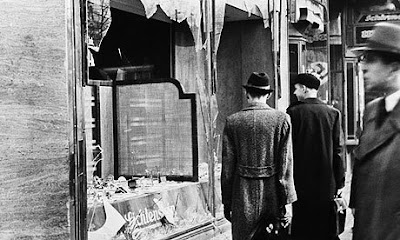

A vandalised shop in Berlin on November 17 1938. Businesses and properties owned by Jews were target of vicious Nazi mobs during the night of vandalism that is known as ‘Kristallnacht’.

Berliners went wild that day, 19 years ago. The impossible had happened. The Wall had come down. It was November 9 1989. I wasn’t there. But I was there on that same date in 1938, 70 years ago. Germans went wild on that day, too. They let loose an orgy of destruction. The synagogues were set ablaze. Jewish shops were smashed up and pillaged. Jewish men were rounded up, beaten up, some to death, many sent to concentration camps. What eventually followed was unthinkable. The streets that night were strewn with broken glass. The Germans called it Kristallnacht, the night not of broken glass but broken crystal, to symbolise the “ill-gotten Jewish riches” Germans would now take from them. Never mind the many Jewish poor. Never mind that Jews such as my grandparents were Germans as deeply patriotic as any of their neighbours.

My Christian father, born to Jewish parents, was in 1938 forbidden, as all Jews were, to continue working as a doctor. From a small provincial town we fled to Berlin with one aim, common to thousands of Jews at that time, to find asylum anywhere beyond the reach of Hitler. An only child, six years old, I was given refuge by kindly non-Jewish friends. Life in their basement flat bore no horrors for me. I simply wondered why I was not allowed to go to school.

My parents had gone underground. My non-Jewish mother had resisted the pressure to divorce her husband and quit a marriage defined by the Nazis as rassenschande, racial disgrace. My father, hoping not to be picked up on the street, as many were, trudged from consulate to consulate, wearing the miniatures of his two iron crosses won in the first world war. Ruefully he said: “In 1918, as a German officer, I fled from the French. Twenty years later, I am fleeing from the Germans.”

Now a visa was priceless. The state had confiscated our bank account. We could not bribe our way to safety. With that visa, Nazi Germany could say good riddance. If Kristallnacht had a definable purpose, beyond its pure explosion of hate, it was to make the Jews go away. But, except for the few who had somehow rescued great wealth, the world did not want them.

The day of the great pogrom started much like any other. But a rare treat was in store. My mother came to take me for a walk. As a non-Jew she was not directly threatened. Berlin was bathed in autumn sunshine. We walked to the Tauentzienstrasse, Berlin’s Regent Street. For me, the big city was full of wonder – until terror struck. Trucks pulled up at exact intervals. Jack-booted men wielding wooden clubs ran up and down the street and began to smash the windows of the Jewish-owned department stores. My mother grabbed hold of me. We fled. I was soon back in a safe place. My parents left Berlin before the day was out and were hidden in Leipzig by a sympathetic member of the Nazi party. In times of crisis, people are not always what they seem to be.

The search for asylum became more desperate. It took us another three months. Many were not so lucky. Nations met at Evian on Lake Geneva to discuss the plight of Germany’s Jews but shrank from their responsibility. No effective policy emerged. At least the Australian delegate was frank: “We have no race problem and we don’t want to import one.” He and many others around the world bought into Hitler’s fanciful racial doctrine. Antisemitism was not just a German aberration. “Why should we import a problem the Germans are so keen to get rid of?” By early 1939, Britain felt “we have done our bit”. President Roosevelt firmly refused to increase the American quota.

Our choice narrowed down to Venezuela and New Zealand. The New Zealand government’s attitude was like that of its neighbour. Jewish applicants were told explicitly: “We do not think you will integrate into our society. If you insist on applying, expect a refusal.” My father did insist. The barriers were high. Either you had a job to come to, at a time of high unemployment, or you had to produce two wealthy guarantors and in addition bring with you, at today’s values, £2,000 per head. We were only able to take that hurdle thanks to the generosity of a remarkable Frenchman, a friend of a distant relative. This was the sort of money most refugees could not possibly raise. At a total of 1,000 German, Austrian and Czech Jews, the New Zealand government drew the line. We were lucky. My grandmother, who hoped to follow us, was not. It was too late. She did not survive the Holocaust. Like many others, she chose suicide rather than the cattle-truck journey to Auschwitz. Britain, thanks to a group of persistent lobbyists, at the last moment agreed to take a substantial number of Jewish children. Most were never to see their parents again. Their contribution to British life was significant, now that the stories of the kindertransport are being told.

I tell my story on this anniversary not just for its historic and personal interest, but because it brings into sharp focus the far from humane attitude of Britain, the European Union and many other rich countries to the asylum seekers of today. True, there are now international conventions that did not exist in 1938, but they are seldom obeyed in spirit or in letter. The German sentiment “send them away” has given way in Britain and in many other parts of Europe to “send them back”, sometimes to more persecution and even death. Lessons from history are seldom learned.

Dr Peter Selby, president of the National Council of Independent Monitoring Boards, has written with justifiable anger of his experience of Britain’s immigration removal centres at ports and airports, which are prisons in all but name. We lock up children, separated from their parents, hold detainees for indefinite periods, and many are made ill by the experience. Those who advocate tougher immigration policies, such as Frank Field’s Migration Watch, are accountable, writes Selby, for the coercive instruments – the destitution and detention – that are already being used and will be used even more to enforce it. This is not quite our 1938, but the parallels are deeply disquieting.

An even sadder consequence of this story of anti-Jewish inhumanity is that many of the survivors who fled to Palestine did so at the expense of the local people, the Palestinians, half of whom were driven into exile and their villages destroyed. Their children and children’s children live in the refugee camps that now constitute one aspect of the Israeli-Palestinian impasse that embitters Islam and threatens world peace: all that a consequence of Nazi terror and indirectly of the Christian world’s persecution of the Jewish people over many centuries.

With fear bred into every Jewish bone, it is tragic that today many Israelis say of the Palestinians, as once the Germans said of them: “The only solution is to send them away.”

However understandable this reaction may be, to do so, or even to contemplate it, is a denial of all that is good in Judaism. To create another victim people is to sow the seeds of another holocaust. When, in the 1930s, the Right Rev George Bell, Bishop of Chichester, pleaded in vain for active British support for the German opposition to Hitler, many accused him of being anti-German. The opposite was true. He did not tar all Germans with the Nazi brush. Today, those of us who offer our solidarity to the minority of Israelis working – in great isolation – for justice for the Palestinian people, are often accused of being antisemitic. The opposite is true. It is a tragic parallel.

November 9 is deeply etched into German history. On that day in 1918 the Kaiser abdicated. Germany had lost the first world war. Five years later to the day, Hitler’s followers were shot down in the streets of Munich. The Nazis, year by year, celebrated their martyrs. Then came 1938: Kristallnacht. Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial and other memorials in many German towns and villages, where once the synagogue stood, are mute reminders of what began that day. But the significance and the shame of that day stretches far beyond those who set the synagogues alight. Who, we need to ask, are the victims now, both near and far, and what is our response?

• Canon Dr Paul Oestreicher is a former chair of Amnesty International UK

Letters November 5th

Canon Paul Oestreicher’s moving account of his childhood experiences in Nazi Germany (The legacy of Kristallnacht, G2, November 4) is spoilt by his suggestion of a “tragic parallel” between that event and Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians. While the recent spate of attacks by Jewish settlers on their West Bank Arab neighbours is contemptible, it does not remotely constitute a modern-day Kristallnacht. Even during the bloodiest periods of both intafadas there were no state-sponsored mass riots; no Arabs were randomly beaten in the streets; mosque windows were not smashed, nor was Arab property burnt to the ground.

If Oestreicher wants to detect echoes of nazism within the Middle East, perhaps he should start with the Hamas charter, which seeks the destruction of Israel. Indeed the virulence of its antisemitism suggests that at least some of the Hamas leadership nurture genocidal ambitions towards Jews. While over a million Arabs live in Israel proper, the Arab and Muslim worlds have become increasingly Judenfrei.

Sidney Jacobs, Exeter

Letters 10th November

The lessons of Kristallnacht for the modern Middle East

Sidney Jacob’s denial (Letters, November 5) of the comparison that Paul Oestreicher draws (The legacy of Kristallnacht, (November 4) is a knee-jerk reaction that seeks to portray Nazi Germany’s attitude to the Jews as a unique, one-off occurrence. Unfortunately there are only too many parallels that can be drawn in the period 1933-39.

When Jewish mobs shouted “death to the Arabs” in Acre a few weeks ago, that was certainly reminiscent of pogroms in Europe. When slogans such as “Arabs to the gas chambers” are daubed on the separation wall, the parallels are also clear. When Israeli military and police stand by while Arabs peasants tending their olive groves are assaulted by settlers, and when even international observers are injured, then that brings to mind a similar refusal by authorities in Germany to uphold the law and protect their Jewish inhabitants.

The lesson of Kristallnacht is surely that any group of people, given the right set of circumstances, can become transformed from oppressed to oppressor. Settler colonialism in Israel-Palestine has reduced the Palestinians to a sub-human status. A majority of Israeli Jews in opinion polls have repeatedly made clear that they don’t wish to live next door to an Arab and would prefer Israel’s own Palestinian citizens to emigrate.

The only part of Paul Oestreicher’s article I disagree with is his suggestion that the vast majority of Germans took part in Kristallnacht. It was a state organised, SA pogrom, orchestrated by the gauleiter of Berlin, Josef Goebbels. It was deeply unpopular with ordinary Germans, as Ian Kershaw’s Hitler Myth makes clear, but by 1938 the ordinary population had been cowed by the Gestapo and the concentration camp apparatus of Nazi Germany.

Tony Greenstein

Brighton