Iraq crisis: How SaudiArabia helped Isis take over the north of the country

an interesting article analysing the Saudi ruling family’s baleful influence on

recent developments in the Middle East, in particular its relationship to Isis.

article appeared in The Independent, whose coverage of the Middle East is by

far and away the best of any British daily paper. It has both Patrick Cockburn and the legendary

Robert Fisk.

Michael Adams, as Middle East contributors, has become increasingly susceptible

to Zionist media pressure.

A speech by an ex-MI6 boss hints at a plan going

back over a decade

back over a decade

|

| Fighters from the Isis group during a parade with a missile in Raqqa, Syria. |

Patrick Cockburn Sunday 13 July 2014

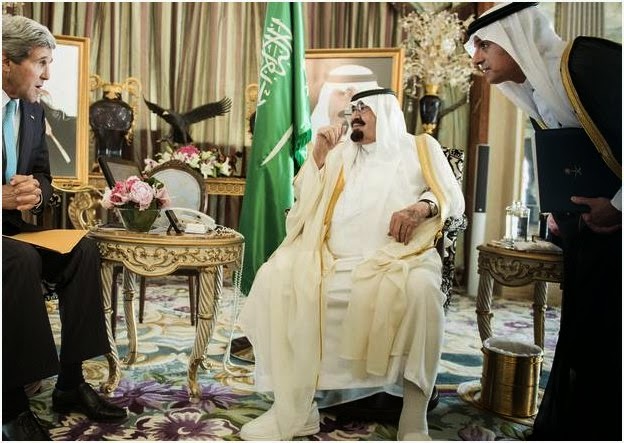

is Saudi Arabia complicit in the Isis takeover of much of northern Iraq, and is

it stoking an escalating Sunni-Shia conflict across the Islamic world? Some

time before 9/11, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, once the powerful Saudi ambassador

in Washington and head of Saudi intelligence until a few months ago, had a

revealing and ominous conversation with the head of the British Secret

Intelligence Service, MI6, Sir Richard Dearlove. Prince Bandar told him:

“The time is not far off in the Middle East, Richard, when it will be

literally ‘God help the Shia’. More than a billion Sunnis have simply had

enough of them.”

|

| Kerry and Binder Sultan, ex-Saudi Ambassador to the United States |

moment predicted by Prince Bandar may now have come for many Shia, with Saudi

Arabia playing an important role in bringing it about by supporting the

anti-Shia jihad in Iraq and Syria. Since the capture of Mosul by the Islamic

State of Iraq and the Levant (Isis) on 10 June, Shia women and children have

been killed in villages south of Kirkuk, and Shia air force cadets

machine-gunned and buried in mass graves near Tikrit.

Shia shrines and mosques have been blown up, and in the nearby Shia Turkoman city

of Tal Afar 4,000 houses have been taken over by Isis fighters as “spoils

of war”. Simply to be identified as Shia or a related sect, such as the

Alawites, in Sunni rebel-held parts of Iraq and Syria today, has become as

dangerous as being a Jew was in Nazi-controlled parts of Europe in 1940.

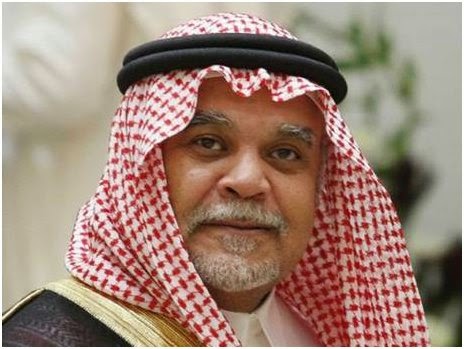

no doubt about the accuracy of the quote by Prince Bandar, secretary-general of

the Saudi National Security Council from 2005 and head of General Intelligence

between 2012 and 2014, the crucial two years when al-Qa’ida-type jihadis took

over the Sunni-armed opposition in Iraq and Syria. Speaking at the Royal United

Services Institute last week, Dearlove, who headed MI6 from 1999 to 2004,

emphasised the significance of Prince Bandar’s words, saying that they constituted

“a chilling comment that I remember very well indeed”.

|

| Prince Bandar bin Sultan |

not doubt that substantial and sustained funding from private donors in Saudi

Arabia and Qatar, to which the authorities may have turned a blind eye, has

played a central role in the Isis surge into Sunni areas of Iraq. He said:

“Such things simply do not happen spontaneously.” This sounds

realistic since the tribal and communal leadership in Sunni majority provinces

is much beholden to Saudi and Gulf paymasters, and would be unlikely to

cooperate with Isis without their consent.

of reckoning for the Shia by Prince Bandar, and the former head of MI6’s view

that Saudi Arabia is involved in the Isis-led Sunni rebellion, has attracted

surprisingly little attention. Coverage of Dearlove’s speech focused instead on

his main theme that the threat from Isis to the West is being exaggerated

because, unlike Bin Laden’s al-Qa’ida, it is absorbed in a new conflict that

“is essentially Muslim on Muslim”. Unfortunately, Christians in areas

captured by Isis are finding this is not true, as their churches are desecrated

and they are forced to flee. A difference between al-Qa’ida and Isis is that

the latter is much better organised; if it does attack Western targets the

results are likely to be devastating.

|

| Sir Richard Dearlove – ex-head of MI6 |

forecast by Prince Bandar, who was at the heart of Saudi security policy for

more than three decades, that the 100 million Shia in the Middle East face

disaster at the hands of the Sunni majority, will convince many Shia that they

are the victims of a Saudi-led campaign to crush them. “The Shia in

general are getting very frightened after what happened in northern Iraq,”

said an Iraqi commentator, who did not want his name published. Shia see the

threat as not only military but stemming from the expanded influence over

mainstream Sunni Islam of Wahhabism, the puritanical and intolerant version of

Islam espoused by Saudi Arabia that condemns Shia and other Islamic sects as

non-Muslim apostates and polytheists.

Iraq crisis: The rise of Isis

says that he has no inside knowledge obtained since he retired as head of MI6

10 years ago to become Master of Pembroke College in Cambridge. But, drawing on

past experience, he sees Saudi strategic thinking as being shaped by two

deep-seated beliefs or attitudes. First, they are convinced that there

“can be no legitimate or admissible challenge to the Islamic purity of

their Wahhabi credentials as guardians of Islam’s holiest shrines”. But,

perhaps more significantly given the deepening Sunni-Shia confrontation, the

Saudi belief that they possess a monopoly of Islamic truth leads them to be

“deeply attracted towards any militancy which can effectively challenge

Shia-dom“.

governments traditionally play down the connection between Saudi Arabia and its

Wahhabist faith, on the one hand, and jihadism, whether of the variety espoused

by Osama bin Laden and al-Qa’ida or by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s Isis. There is

nothing conspiratorial or secret about these links: 15 out of 19 of the 9/11

hijackers were Saudis, as was Bin Laden and most of the private donors who

funded the operation.

|

| Sunni Ahmed al-Rifai shrine near Tal Afar is bulldozed |

difference between al-Qa’ida and Isis can be overstated: when Bin Laden was

killed by United States forces in 2011, al-Baghdadi released a statement

eulogising him, and Isis pledged to launch 100 attacks in revenge for his

death.

has always been a second theme to Saudi policy towards al-Qa’ida type jihadis,

contradicting Prince Bandar’s approach and seeing jihadis as a mortal threat to

the Kingdom. Dearlove illustrates this attitude by relating how, soon after

9/11, he visited the Saudi capital Riyadh with Tony Blair.

remembers the then head of Saudi General Intelligence “literally shouting

at me across his office: ‘9/11 is a mere pinprick on the West. In the medium

term, it is nothing more than a series of personal tragedies. What these

terrorists want is to destroy the House of Saud and remake the Middle

East.'” In the event, Saudi Arabia adopted both policies, encouraging the

jihadis as a useful tool of Saudi anti-Shia influence abroad but suppressing

them at home as a threat to the status quo. It is this dual policy that has

fallen apart over the last year.

sympathy for anti-Shia “militancy” is identified in leaked US

official documents. The then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton wrote in

December 2009 in a cable released by Wikileaks that “Saudi Arabia remains

a critical financial support base for al-Qa’ida, the Taliban, LeT

[Lashkar-e-Taiba in Pakistan] and other terrorist groups.” She said that,

in so far as Saudi Arabia did act against al-Qa’ida, it was as a domestic

threat and not because of its activities abroad. This policy may now be

changing with the dismissal of Prince Bandar as head of intelligence this year.

But the change is very recent, still ambivalent and may be too late: it was

only last week that a Saudi prince said he would no longer fund a satellite

television station notorious for its anti-Shia bias based in Egypt.

problem for the Saudis is that their attempts since Bandar lost his job to

create an anti-Maliki and anti-Assad Sunni constituency which is simultaneously

against al-Qa’ida and its clones have failed.

seeking to weaken Maliki and Assad in the interest of a more moderate Sunni

faction, Saudi Arabia and its allies are in practice playing into the hands of

Isis which is swiftly gaining full control of the Sunni opposition in Syria and

Iraq. In Mosul, as happened previously in its Syrian capital Raqqa, potential

critics and opponents are disarmed, forced to swear allegiance to the new

caliphate and killed if they resist.

may have to pay a price for its alliance with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf

monarchies, which have always found Sunni jihadism more attractive than

democracy. A striking example of double standards by the western powers was the

Saudi-backed suppression of peaceful democratic protests by the Shia majority

in Bahrain in March 2011. Some 1,500 Saudi troops were sent across the causeway

to the island kingdom as the demonstrations were ended with great brutality and

Shia mosques and shrines were destroyed.

used by the US and Britain is that the Sunni al-Khalifa royal family in Bahrain

is pursuing dialogue and reform. But this excuse looked thin last week as

Bahrain expelled a top US diplomat, the assistant secretary of state for human

rights Tom Malinowksi, for meeting leaders of the main Shia opposition party

al-Wifaq. Mr Malinowski tweeted that the Bahrain government’s action was

“not about me but about undermining dialogue”.

leader al-Maliki Western powers and their regional allies have largely escaped

criticism for their role in reigniting the war in Iraq. Publicly and privately,

they have blamed the Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki for persecuting and

marginalising the Sunni minority, so provoking them into supporting the

Isis-led revolt. There is much truth in this, but it is by no means the whole

story. Maliki did enough to enrage the Sunni, partly because he wanted to

frighten Shia voters into supporting him in the 30 April election by claiming

to be the Shia community’s protector against Sunni counter-revolution.

all his gargantuan mistakes, Maliki’s failings are not the reason why the Iraqi

state is disintegrating. What destabilised Iraq from 2011 on was the revolt of

the Sunni in Syria and the takeover of that revolt by jihadis, who were often

sponsored by donors in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and United Arab Emirates.

Again and again Iraqi politicians warned that by not seeking to close down the

civil war in Syria, Western leaders were making it inevitable that the conflict

in Iraq would restart. “I guess they just didn’t believe us and were fixated

on getting rid of [President Bashar al-] Assad,” said an Iraqi leader in

Baghdad last week.

course, US and British politicians and diplomats would argue that they were in

no position to bring an end to the Syrian conflict. But this is misleading. By

insisting that peace negotiations must be about the departure of Assad from

power, something that was never going to happen since Assad held most of the

cities in the country and his troops were advancing, the US and Britain made

sure the war would continue.

beneficiary is Isis which over the last two weeks has been mopping up the last

opposition to its rule in eastern Syria. The Kurds in the north and the

official al-Qa’ida representative, Jabhat al-Nusra, are faltering under the

impact of Isis forces high in morale and using tanks and artillery captured

from the Iraqi army. It is also, without the rest of the world taking notice,

taking over many of the Syrian oil wells that it did not already control.

Al-Qubba Husseiniya mosque in Mosul explodes Saudi Arabia has created a

Frankenstein’s monster over which it is rapidly losing control. The same is

true of its allies such as Turkey which has been a vital back-base for Isis and

Jabhat al-Nusra by keeping the 510-mile-long Turkish-Syrian border open. As

Kurdish-held border crossings fall to Isis, Turkey will find it has a new

neighbour of extraordinary violence, and one deeply ungrateful for past favours

from the Turkish intelligence service.

Saudi Arabia, it may come to regret its support for the Sunni revolts in Syria

and Iraq as jihadi social media begins to speak of the House of Saud as its

next target. It is the unnamed head of Saudi General Intelligence quoted by

Dearlove after 9/11 who is turning out to have analysed the potential threat to

Saudi Arabia correctly and not Prince Bandar, which may explain why the latter

was sacked earlier this year.

this the only point on which Prince Bandar was dangerously mistaken. The rise

of Isis is bad news for the Shia of Iraq but it is worse news for the Sunni

whose leadership has been ceded to a pathologically bloodthirsty and intolerant

movement, a sort of Islamic Khmer Rouge, which has no aim but war without end.

caliphate rules a large, impoverished and isolated area from which people are

fleeing. Several million Sunni in and around Baghdad are vulnerable to attack

and 255 Sunni prisoners have already been massacred. In the long term, Isis

cannot win, but its mix of fanaticism and good organisation makes it difficult

to dislodge.

help the Shia,” said Prince Bandar, but, partly thanks to him, the

shattered Sunni communities of Iraq and Syria may need divine help even more

than the Shia.