|

| Erdogan denies proven oil links with Isis |

ISIS to the Kurds

Vladimir Putin that Turkey was actively complicit in buying oil from ISIS President

Erdogan challenged him to prove it and if he couldn’t to stand down.

|

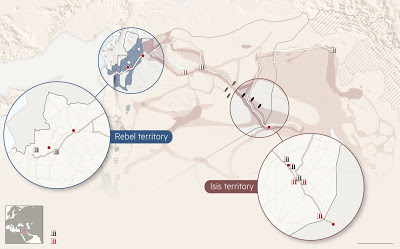

| The ISIS – Turkey oil route |

Putin could prove it.

will resign but the evidence is quite clear.

Below is the response of the Russian Government to the challenge thrown down by Erdogan.

|

| Erdogan keeps out the oil |

relationship hinted at by Russian leader after warplane was shot down is a

complex one, and includes links between senior Isis figures and Turkish

officials

|

| Bilal Erdogan – in charge of the oil trade with ISIS |

Since the earliest months of the Syrian war, Turkey has had more direct involvement and

more at stake than any of the regional states lined up against Bashar al-Assad.

Turkish borders have been the primary thoroughfare for fighters of all kinds

to enter Syria. Its

military bases have been used to distribute weapons and to train rebel

fighters. And its frontier towns and villages have taken in almost one million

refugees.

Turkey’s international airports have also been busy. Many, if not most, of

the estimated 15,000-20,000 foreign fighters to have joined Islamic State (Isis) have first flown into

Istanbul or Adana, or arrived by ferry along its Mediterranean coast.

The influx has offered fertile ground to allies of Assad who, well before a

Turkish jet shot down a Russian fighter on Tuesday, had claimed Turkey had

enabled or even supported Isis. Vladimir Putin’s

reference to Turkey as “accomplices of terrorists” is likely to resonate

even among some of Ankara’s backers.

|

| Protest in Parliament Square |

From

midway through 2012, when jihadis started to travel to Syria, their presence

was apparent at all points of the journey to the border: at Istanbul airport,

in the southern cities of Hatay and Gaziantep – both of which were staging

points – and in the border villages. Foreigners on their way to fight remained

fixtures on these routes until late in 2014 when, after continued pressure from

the EU states and the US, coordinated efforts were made to turn them back.

|

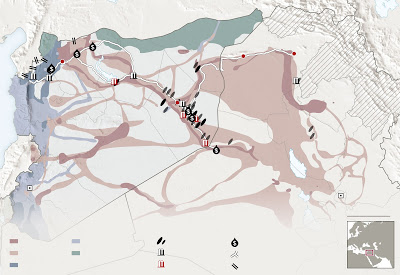

| Syrian oil map – the ourney of a barrel |

By then, Isis had become a dominant presence in parts of north and east

Syria. It had splintered non-ideological factions of the Syrian opposition as

well as Islamist groups, both of which had been backed by Turkey, and ensured

that whatever form of governance that emerged from Syria’s ruins would have

little to do with the revolution’s original goals.

|

| Turkey shot down Russian aircraft to protect oil supplies |

The steady stream of foreigners who passed through Hatay and Gaziantep made

little effort to remain discreet, gathering regularly in local hotels, coffee

shops and bus stations. European diplomats alarmed by the gathering threat

concluded that the Turkish leadership was sympathetic to conservative Islamists

travelling to fight Assad, who had, until his brutal response to

pro-democracy demonstrations in 2011, been a friend of the Turkish

president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. “After that he became an enemy,” said one

western official. “Erdoğan had tried to mentor Assad. But after the crackdown

[on demonstrations] he felt insulted by him. And we are where we are today.”

|

| ‘Commercial scale’ oil smuggling into Turkey becomes priority target of anti-ISIS strikes. “ |

As Syria unravelled, Turkey doubled down on its commitment to a range of

militant groups, while at the same time appearing to recognise that the jihadis

who had passed through their territory were hardly a benign threat. The change

in the dialogue with western officials was marked: security officials no longer

insisted on the extremists being called “those who abuse religion”. Labelling

them “terrorists” in official correspondence was no longer the problem it had

been.

Despite

that, links to some aspects of Isis continued to develop. Turkish businessmen

struck lucrative deals with Isis oil smugglers, adding at least $10m (£6.6m)

per week to the terror group’s coffers, and replacing the Syrian regime as its

main client. Over the past two years several senior Isis members have told the

Guardian that Turkey preferred to stay out of their way and rarely tackled them

directly.

Concerns continued to grow in intelligence circles that the links eclipsed

the mantra that “my enemy’s enemy is my friend” and could no longer be

explained away as an alliance of convenience. Those fears grew in May this year

after a US special forces

raid in eastern Syria, which killed the Isis official responsible for the

oil trade, Abu Sayyaf.

A trawl through Sayyaf’s compound uncovered hard drives that detailed

connections between senior Isis figures and some Turkish officials. Missives

were sent to Washington and London warning that the discovery had “urgent

policy implications”.

Shortly

after that, Turkey opened a new front against the Kurdish separatist group, the

PKK, with which it had fought an internecine war for close to 40 years. In

doing so, it allowed the US to begin using its Incirlik air base for operations

against Isis, pledging that it too would join the fray. Ever since, Turkey’s

jets have aimed their missiles almost exclusively at PKK targets inside its

borders and in Syria, where the YPG, a military ally of the PKK, has been the

only effective fighting force against Isis – while acting under the cover of US

fighter jets.

Senior Turkish officials have openly stated that the Kurds – the main US

ally in Syria – pose more of a threat than Isis to Turkey’s national interests.

Yet, through it all, Turkey, a Nato member, continues to be regarded as an ally

by Europe. The

US and Britain have become far less enamoured, but are unwilling to do much

about it. The worry in both capitals is that to do so would introduce yet

another variable into an already highly volatile region, where alliances,

strategies, and implications are constantly changing.

“Turkey thought they could control it all,” said one senior western

official. “But it got out of their hands. It has come back to bite them in the

heart of Ankara [a double suicide bombing in October that was claimed by Isis]

and it will haunt them for a long time.”

Turkey could cut off Islamic State’s supply lines. So why doesn’t it?

Western leaders could destroy Islamic State by calling on Erdoğan to end his

attacks on Kurdish forces in Syria and Turkey and allow them to fight Isis on

the ground

In the wake of the murderous attacks in Paris,

we can expect western heads of state to do what they always do in such

circumstances: declare total and unremitting war on those who brought it about.

They don’t actually mean it. They’ve had the means to uproot and destroy

Islamic State within their hands for over a year now. They’ve simply refused to

make use of it. In fact, as the world watched leaders making statements of

implacable resolve at the G20 summit in

Antalaya, these same leaders are hobnobbing with Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan,

a man whose tacit political, economic, and even military support contributed to

Isis’s ability to perpetrate the atrocities in Paris, not to mention an endless

stream of atrocities inside the Middle East.

How

could Isis be eliminated? In the region, everyone knows. All it would really

take would be to unleash the largely Kurdish forces of the YPG (Democratic

Union party) in Syria, and PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ party) guerillas in Iraq and

Turkey. These are, currently, the main forces actually fighting Isis on the

ground. They have proved extraordinarily

militarily effective and oppose every aspect of Isis’s reactionary

ideology.

But instead, YPG-controlled territory in Syria finds itself placed under a

total embargo by Turkey, and

PKK forces are under continual bombardment by the Turkish air force. Not only

has Erdoğan done almost everything he can to cripple the forces actually

fighting Isis; there is considerable evidence that his government has been at

least tacitly aiding Isis itself.

It might seem outrageous to suggest that a Nato member like Turkey would in

any way support an organisation that murders western civilians in cold blood.

That would be like a Nato member supporting al-Qaida. But in fact there is

reason to believe that Erdoğan’s government does support the

Syrian branch of al-Qaida (Jabhat al-Nusra) too, along with any number of

other rebel groups that share its conservative Islamist ideology. The Institute

for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University has compiled a long list

of evidence of Turkish support for Isis in Syria.

How

has Erdoğan got away with this? Mainly by claiming those fighting Isis are

‘terrorists’ themselves

And

then there are Erdoğan’s actual, stated positions. Back in August, the YPG,

fresh from their victories in Kobani and Gire

Spi, were poised to seize Jarablus, the last Isis-held town on the Turkish border that the terror

organisation had been using to resupply its capital in Raqqa with weapons,

materials, and recruits – Isis supply lines pass directly through Turkey.

Commentators predicted that with Jarablus gone, Raqqa would soon follow. Erdoğan reacted by

declaring Jarablus a “red line”: if the Kurds attacked, his forces would

intervene militarily – against the YPG. So Jarablus remains in terrorist hands

to this day, under de facto Turkish military protection.

How has Erdoğan got away with this? Mainly by claiming those fighting Isis

are “terrorists” themselves. It is true that the PKK did fight a sometimes ugly

guerilla war with Turkey in the 1990s, which resulted in it being placed on the

international terror list. For the last 10 years, however, it has completely

shifted strategy, renouncing separatism and adopting a strict policy of never

harming civilians. The PKK was responsible for rescuing thousands of Yazidi civilians

threatened with genocide by Isis in 2014, and its sister organisation, the YPG,

of protecting Christian communities in Syria as well. Their strategy focuses on

pursuing peace talks with the government, while encouraging local democratic

autonomy in Kurdish areas under the aegis of the HDP, originally a nationalist

political party, which has reinvented itself as a voice of a pan-Turkish

democratic left.

They have proved extraordinarily militarily effective and with their embrace

of grassroots democracy and women’s rights, oppose every aspect of Isis’

reactionary ideology. In June, HDP success at the

polls denied Erdoğan his parliamentary majority. Erdoğan’s response was

ingenious. He called for new elections,

declared he was “going to war” with Isis, made one token symbolic attack on

them and then proceeded to unleash the full force of his military against PKK

forces in Turkey and Iraq, while denouncing the HDP as “terrorist supporters”

for their association with them.

There followed a series of increasingly bloody terrorist bombings inside

Turkey – in the cities of Diyarbakir, Suruc, and, finally, Ankara – attacks

attributed to Isis but which, for some mysterious reason, only ever seemed to

target civilian activists

associated with the HDP. Victims have repeatedly reported police preventing ambulances evacuating the wounded,

or even opening fire on survivors with tear gas.

As

a result, the HDP gave up even holding political rallies in the weeks leading

up to new elections in November for fear of mass murder, and enough HDP voters

failed to show up at the polls that Erdoğan’s party secured a majority in

parliament.

The exact relationship between Erdoğan’s government and Isis may be subject

to debate; but of some things we can be relatively certain. Had Turkey placed

the same kind of absolute blockade on Isis territories as they did on

Kurdish-held parts of Syria, let alone shown the same sort of “benign neglect”

towards the PKK and YPG that they have been offering to Isis, that

blood-stained “caliphate” would long since have collapsed – and

arguably, the Paris attacks may never have happened. And if Turkey were to do

the same today, Isis would probably collapse in a matter of months. Yet, has a

single western leader called on Erdoğan to do this?

The next time you hear one of those politicians declaring the need to crack

down on civil liberties or immigrant rights because of the need for absolute

“war” against terrorism bear all this in mind. Their resolve is exactly as

“absolute” as it is politically convenient. Turkey, after all, is a “strategic

ally”. So after their declaration, they are likely to head off to share a

friendly cup of tea with the very man who makes it possible for Isis to

continue to exist.