Racist Violence is what a Jewish state means in practice – Settler Reign of Terror During Palestinian Olive Harvest Courtesy of Israeli Security Forces

Israel’s Bar Ilan University warns Jewish students they will have to share dorms with Palestinian students

There really is little need to comment on this headline because it speaks for itself. It is based on a report in Hebrew. It used to be the case that Bar Ilan, a religious university in Tel Aviv used to have separate dorms for Arab and Jewish students. However after the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin by a student of Bar Ilan, Yigal Amir, there had to be some changes.

Jewish students in most Israeli universities are given the option of whether or not to share their accommodation with Palestinian Israeli students. After all isn’t that what a Jewish State is about?

When Keir Starmer told the Times of Israel

‘I said it loud and clear — and meant it — that I support Zionism without qualification.”

what he meant was that he supported segregation and Jewish supremacy, because that is what Zionism means. And if you said that the Zionist idea of separating Jews and Palestinians was racist, I’m sure that Starmer would say that you were being ‘anti-Semitic’. Because an anti-Semite these days is now being redefined as an anti-racist. Bizarre isn’t it whilst actual racists like Steve Bannon and Richard Spencer are ‘supporters of the Jewish people’ and not anti-Semitic. That is what is mean by newspeak.

Is it racist to allow and permit segregation in education? Perish the thought. This is self-determination!

In another example of what a Jewish state means I have copied 3 stories below about the reign of terror against Palestinian farmers in the West Bank, especially during the olive growing season.

The article below describes the reign of terror that the illegal settlement of Yizhar wages against neighbouring Palestinian villages. Not only does the Israeli army not protect the Palestinians but it actively protects the attackers and fires tear gas grenades into the homes of those under attack.

This aiding and abetting Israeli settler terrorists is exactly what used to happen when Jews in Russia came under attack from pogromists. The Russian police only intervened when the Jews began to fight back against the anti-Semites. So it is with Israel today. Yet this is the situation that the execrable Starmer, fully backed by the pathetic Momentum and the even more pathetic John McDonnell supports when they classify anti-Zionism as ‘anti-Semitism’. Because that is what the fake ‘anti-Semitism’ campaign and now the EHRC Report is about.

The second article is a Ha’aretz leading article on the wave of terror directed at Palestinian farmers. It excoriates the Israeli Police for deliberately turning a blind eye to settler violence. Just 9% of cases result in any form of police prosecution or action.

The third article describes the attack on an elderly Palestinian farmer, aged 73. He had a large rock thrown at his head by 4 Jewish terrorists. The Zionist Police of course did nothing. This is the state of affairs in the ‘only democracy in the Middle East’.

Tony Greenstein

At the Foothills of an Israeli Settlement, Palestinians Are Used to Weekends of Terror

Five people wounded – that was the bloody toll of two assaults last weekend by settlers from Yitzhar and its neighboring outposts on Palestinian villagers in the West Bank. Guess which of the sides gets army protection

Mohammed Zaben and his father Imad, in a neck brace. “In the name of God, don’t throw stones at us,” they pleaded with the settlers, who kept up their barrage.

Mohammed Zaben and his father Imad, in a neck brace. “In the name of God, don’t throw stones at us,” they pleaded with the settlers, who kept up their barrage.

Published on 30.10.2020

The last row of houses in the village of Asira al-Qibliya, near Nablus in the West Bank, looks like a sort of fortress. Eight residential dwellings whose windows are protected with bars, courtesy of a European aid organization, their yards covered with a smattering of stones that have been thrown at them, encompassed by a fence, doors shuttered. The violent mountaintop settlement of Yitzhar next door has the people of this outlying region – not to say war zone – cringing with terror. The mobile homes of Shalhevet, one of nine unauthorized outposts that Yitzhar has spawned, are visible from the yard of the last house in Asira, looming ominously on a hilltop above the rest of the Palestinian village.

Across the way is an Israel Defense Forces base whose soldiers almost always show up together with the settler-ruffians, protecting them and sometimes also joining in the attacks on their Palestinian victims, firing live rounds into the air as well as stun grenades and tear gas. Next to Shalhevet’s trailers stands a round green structure. When there’s a light on inside, villagers say, they’re calm, but when it’s dark it’s a sign that yet another “price tag” action – some sort of retaliatory act – can be expected. Hence their name for the structure: the “price tag building.”

Occupants of that last row of homes in Asira know the drill: gather the children into one room, especially on weekends – “Friday-Saturday” is synonymous here with settler assaults – and turn up the volume of the television when they approach, so the frightened children won’t hear the barrage of stones the settlers let loose at their homes or the sounds of the soldiers’ stun grenades and shooting. Every night of the week a man from a different family stays awake to guard and to warn others if something is happening. That’s been the routine for almost 20 years. Last weekend, too.

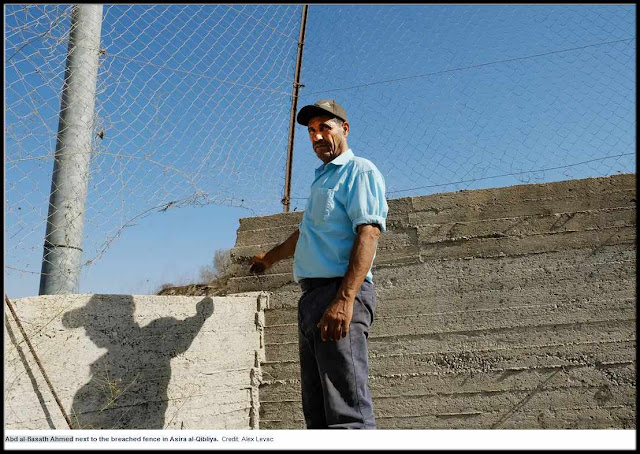

Abd al-Basath Ahmed is a hardscrabble construction worker of 50 and the father of seven children, one of them with special needs. Last Saturday, he was at home with his wife Maisa and the family while the neighbors, some of them his relatives, went out to harvest olives in their groves nearby. Ahmed’s house and that of one of his sons are the last two houses in Asira; a simple metal fence separates them from a valley below and the hill on the other side where Yitzhar is perched. The fence was torn this week, following the latest attack by the settlers.

At about 3:30 P.M. on Saturday, he told us when we visited this week, Ahmed’s nephew, who lives in the house behind his, called to say that he could see settlers descending from the mountain. Ahmed immediately looked outside. This time they were coming from the northeast, from the direction of Shalhevet. Ahmed spotted a group of 18 to 20 settler men, dressed in white – they always wear white, in honor of the Sabbath – marching down the slope of the hill toward the village. When they drew closer they put on masks, as they always do. They carried stones. Big ones, some of them folded up in their shirts. Ahmed’s impression was that they were an organized group, all apparently in their 20s.

Quickly he hustled the children and grandchildren into his house and went up to the roof with Maisa to see what lay in store. The raiders were busy breaching the metal fence outside his yard. Ahmed decided to go down to try to stop them, a stick in his hand. His fear was that the group would break into his house, and he was the only adult male left in the area; all the others were helping in the olive harvest.

The settlers tore open the fence, and one of them entered the yard. A hail of stones was unleashed by the others. Ahmed had nowhere to escape and no way of protecting himself. One stone struck his skull, another his left shoulder and a third slammed into his thigh, smashing the mobile phone in his pocket. The settlers didn’t utter a word, he recalled, only threw stones.

Israel’s Illegitimate ‘Demographic Balance’

Abd al-Basath Ahmed next to the breached fence in Asira al-Qibliya.Credit: Alex Levac

Settlers Hurled Rocks at the Palestinian Farmer’s Head. His Age Didn’t Deter Them

Ahmed is wearing stained work clothes, his face etched with weariness, as he talks to us. As blood streamed from his head, he says, the settlers retreated: They had had enough. But by then, the army had arrived from the hill across the way, from the all-seeing base overlooking the entire area. As usual, the mission of the soldiers, six in number this time, was to protect the assailants. They aimed stun grenades at Ahmed’s house, while acting as a buffer between it and the settlers and firing live ammunition in the air. The empty casings remained in his yard. Material evidence.

The soldiers were relatively restrained this time, Ahmed relates: Breaking with custom, they didn’t fire tear gas into the house. He terms this a “gesture.” He has a permanent kit to be used against tear gas, at home: rags soaked in a solution of baking soda. It helps, he says. They also have a fire extinguisher, for any contingency.

The settlers actually renewed their stone throwing when the soldiers showed up. Hiding behind the troops, they apparently felt safer, more protected. The soldiers didn’t lift a finger to stop them – they never do, Ahmed says. They ordered him to hide until a Palestinian ambulance arrived to take him for treatment. He sat in a corner of the yard, blood oozing from his head; Maisa tried to stanch the bleeding with a piece of cloth. In the meantime, seven more settlers showed up to join their friends. Ahmed waited an hour for the ambulance to arrive; the soldiers made no effort to assist or evacuate him.

The IDF Spokesperson’s Office issued the following response on Wednesday to Haaretz:

“Last Saturday, there was friction between Israelis and Palestinians in the village of Asira al-Qibliya, which involved the throwing of stones by both sides. An IDF force was dispatched to the scene to serve as a barrier between those disturbing the peace, in order to put an end to the incident, among other ways by means of crowd dispersal. As opposed to what has been claimed, the stun grenades that were in use were not directed at the house in the village.”

Ahmed was taken to Rafadiya Hospital in Nablus, where he received six stitches in his head and then was released.

Asira al-Qibliya.Credit: Alex Levac

A few months ago, when the Israeli Civil Administration removed a mobile home, deemed illegal in Yitzhar, the settlers’ attacks intensified, taking place daily over the course of a week. That was the outlet for their anger.

This situation has continued unabated since 2002. In some cases the settlers raid the village at night and damage residents’ cars – as they did in 2012, setting some vehicles on fire – but for the most part they attack the houses at the edge of the village stones, and don’t dare enter it.

In April, Ahmed’s brother planted a fig tree in the area between his house and the hill across the valley. Yitzhar’s security officer arrived immediately and ordered him to uproot the tree. He refused. The next morning he found the tree had been set on fire.

Two years ago, the same brother tried to file a complaint with the police after settlers torched his taxi. Following a humiliating wait of hours, he was told by the police that he hadn’t paid an old traffic ticket, and that unless he did so they would not accept his complaint. Since then, the family has stopped making complaints to the police about the attacks on them.

In some instances the settlers arrive only to provoke or frighten the villagers. They take up positions next to the metal fence near the houses and dance and sing. One way or another, there isn’t a quiet Saturday.

“And now another Shabbat is coming,” Ahmed told us with a bitter smile before we parted.

One of Imad Zaben’s sons, who asked his name not be used, his hand in a cast. Credit: Alex Levac

The yard of a house in another village, Burin, on the other side of Yitzhar. Imad Zaben, a blacksmith of 59, sits surrounded by his wife and children, wearing a neck brace following the spinal surgery he underwent three weeks ago.

Last Friday, the day before the attack on Asira al-Qibliya, wearing his brace, Zaben and his family – his wife, his brother and some children and grandchildren – were harvesting olives in the family grove about three kilometers from Yitzhar, in the valley below. Never had they encountered problems during the harvest; this time, too, the day began quietly.

But after a few uneventful hours, at around 12:30, stones began to rain down on them from above. Zaben’s son, Mohammed, 32, suffered a skull fracture when he was struck by a stone. Another son, 28 (who asked that his name not be used), suffered a broken arm; a stone fractured the arm of Zaben’s brother, Bashir, 64; and his nephew, Ahmed, 34, Bashir’s son, was also struck in the arm. All told, four members of one family were injured. Zaben, who was careful and very worried because of his back surgery, managed to emerge unscathed; his sons protected him bodily.

The rain of stones surprised them: Because the settlers throwing them were situated above them, just meters away, on the hill, initially, the Zaben family didn’t see them.

“In the name of God, don’t throw stones at us,” they pleaded with the settlers, who didn’t utter a word but kept up their barrage – as in Asira the following day.

Despite his head injury Mohammed rode off on the horse he had brought to the site, and the settlers started to flee, though not before throwing a few more stones. Other members of the family quickly got into their cars and hurried home. Mohammed was taken by ambulance to Rafadiya Hospital and from there was transferred to the intensive care unit in Istishari Hospital in Ramallah. He was discharged after three days.

The Zaben family won’t be returning to their grove this harvest season.

Editorial |

Settler Violence Against Palestinian Farmers Only Grows During Harvest Time

Destroyed olive tree in the village of Mreir, West Bank, January 24, 2019.Credit: Alex Levac

Not even the coronavirus pandemic, which has derailed the entire world, managed to stop the seasonal outbreak of settler violence during the olive harvest, or the odor of collaboration by Israeli law enforcement agencies that always accompanies it.

On the contrary, according to one of the leaders of the Palestinian activist organization Faz3a, which sends volunteers to the orchards to help Palestinian farmers, this year has seen a rise in the number of violent incidents and in the level of settler aggression. The Israeli organization Yesh Din: Volunteers for Human Rights has documented 25 incidents related to the harvest since the harvest season began. These range from stealing olives to burning or chopping down trees to violent assaults on the harvesters. To date, more than 400 trees have been cut down and around 50 have been torched.

The economic fallout from the pandemic has not spared the occupied territories. As a result, the olive harvest has become a primary source of income for many families. The lawless settlers who steal the olives and uproot the trees aren’t only vandalizing Palestinian property; they are also sabotaging the livelihoods of entire families at a very difficult time.

Ohad Hemo of Channel 12 Television News reported on settler violence during the harvest last week. A moment before he and his crew were attacked by criminals from the settlements, he filmed a masked settler telling a landowner from the Palestinian village of Burqa, “God gave us this land. I’m the son of Allah and you are his slave.” This ugly arrogance captures perfectly the sick mood that has been spreading through the settlements. The Jews are the lords of the land and the Palestinians are slaves, even when the Palestinians are the legal owners of that land.

Israeli Police Investigating Uprooting of Olive Trees in West Bank Village

Palestinian Farmers Lose Hundreds of Olive, Fig Trees to West Bank Vandals

Hundreds of Trees Destroyed in West Bank Palestinian Villages, Israeli Rights Groups Report

But the settlers would not be so successful in their oppression and theft were it not for the inaction of Israeli law enforcement agencies, which do almost nothing to bring criminals from the hilltop outposts to justice. According to Yesh Din’s figures, only nine percent of investigations into cases in which Israelis assaulted Palestinians or damaged their property in the West Bank from 2005 to 2019 ended in charges being filed against the suspects. Fully 82 percent of these cases were closed for reasons that attest to the police’s failure to investigate. And when it comes to investigations into vandalizing trees, the percentage of cases in which anyone is indicted is even lower.

These pogroms are taking place in the name of Israel as a whole, and Israel as a whole bears responsibility for them. The law enforcement agencies, and especially the Judea and Samaria District police, treat Palestinian complainants with abysmal contempt and fail to prosecute violent settlers even when their actions and their identities have been fully documented. In effect, the state is telling the lawbreakers that they can continue to commit crimes without let or hindrance. Israel has thereby revealed its great and hidden goal – pushing the Palestinians out of the occupied territories.

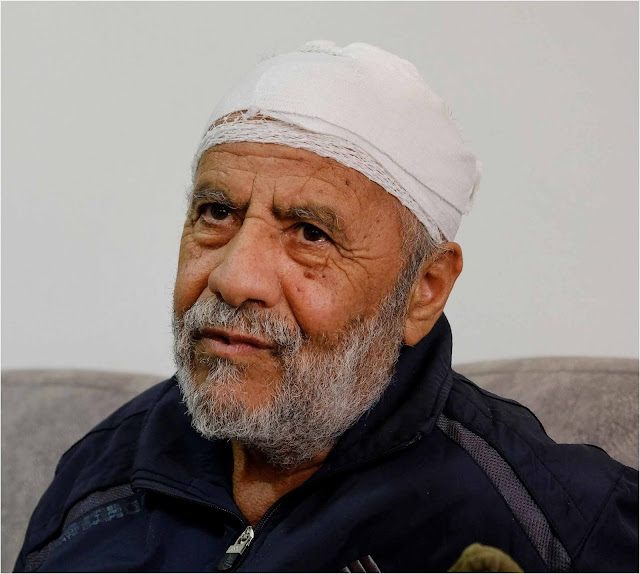

Settlers Hurled Rocks at the Palestinian Farmer’s Head. His Age Didn’t Deter Them

Settlers stoned and injured a 73-year-old Palestinian in his grove, others vandalized another farmer’s 200 trees. A journey during the season of harvest – which is also clearly the season of settler violence

At home on the outskirts of the West Bank village of Na’alin, an elderly farmer, Khalil Amira, is nursing a head wound he suffered when settlers stoned him while he harvested olives in his grove – in front of his daughter and grandchildren. About an hour’s drive south, in the village of Jab’a, two other aged farmers are lamenting the damage wrought to their olive trees by other thugs. And these are only three recent examples of the dozens of Palestinian harvesters who are being assaulted on their lands on an almost daily basis.

It’s autumn, with its clouds and its howling wind, as the old Israeli song goes, and it’s also the season of the olive harvest – and with it settlers who go on a rampage every year at this time, across the West Bank. It’s not autumn if there’s no olive harvest, and there’s no olive harvest without settler rampages. And the start of this season bodes ill.

Several weeks into the harvest, which began this year on October 5, the Yesh Din – Volunteers for Human Rights NGO has already documented 25 violent incidents, and no one apparently intends to put a stop to them. The police accept complaints and take down testimonies, but that seems to be the extent of their activity.

According to Yesh Din, between 2005 and 2019, only 9 percent of the complaints filed by Palestinians over Israelis’ violence against them ended with the alleged perpetrators being brought to trial. Fully 82 percent of the cases were closed, including nearly all of the complaints about the destruction of olive trees.

Amira is surrounded by family in his fine house in Na’alin, west of Ramallah. His head is bandaged, concealing 15 stitches; his family envelops him with concern and warmth. Since being wounded last week by a stone thrown at him by settlers, he’s returned to the hospital twice, because of possible intracranial bleeding. A working man of 73, Amira was employed for 20 years as a welder in the predominantly ultra-Orthodox city of Bnei Brak, in Israel; he also worked for years at Elco, an industrial conglomerate. His father left him, his two sisters and his six brothers 100 dunams (25 acres) of olive trees, which he has been cultivating since his retirement, after becoming ill with a heart ailment. He speaks Hebrew fluently, and he and his family are gracious hosts.

Khalil Amira at his home. Credit: Alex Levac

Amira’s access to his land was cut off in 2008 by the construction of the West Bank separation barrier – a fate that befell many Palestinian farmers. Part of his property was also expropriated for the establishment of a settlement called Hashmona’im, which is on the other side of the barrier, yet another annexation-type stunt. Recently, settlers ruined the two wells that were his on land adjacent to Hashmona’im. They would descend into one of the wells with a ladder and wash themselves in it, contaminating the water. The settlers also made a breach in the fence that encircles Hashmona’im and dumped garbage and construction debris on another part of his land – the evidence is still there. Amira filed a complaint with the Binyamin District police, and the dumping stopped for a time, but it resumed last February. It was clear that the perpetrators of the recent assault on him also set out from Hashmona’im, even if they were not necessarily residents of the settlement.

For 11 years, the farmer was unable to visit the land he owns, adjacent to the fence surrounding Hashmona’im – others were able to work it for him – until last fall, when he was able to harvest his olives with no interference. He wanted to do the same this year. The Israel Defense Forces allow him four days to pick olives – with advance coordination. Amira was supposed to start picking Monday last week, but because of a doctor’s appointment, he didn’t arrive until the following day.

- Palestinian Volunteers Help Olive Harvesters in Ways the Palestinian Authority Can’t

- ‘What Hell Feels Like’: Israel Demolished This Palestinian Family’s Hut. They Have Nowhere to Go

- Why Israelis Care About the Killing of an Autistic Palestinian, but Are Silent About Others

They set out early in the morning: Amira, his son Raad, 47, his daughter Halda, 35, and three young grandchildren. The IDF does not permit them to arrive at their lands by vehicle, so they had to walk about a kilometer from the gate in the separation fence. By about midday they had collected enough olives to fill a large sack. Raad hoisted a bag with half of the olives onto his shoulder and carried it to the gate, and then returned for the other half. Seeing that Raad was tired, his father told him he didn’t have to come back again.

At 2:30 P.M., Amira hid the tools he had used in the grove, before his departure. When he returned from the hiding place, he saw that his daughter and grandchildren had already left. On his way to the gate he saw his grandson’s knapsack on the ground. He picked it up and continued to walk, when suddenly he heard shouts.

In a nearby grove, he saw four masked young people throwing rocks at his nephew, Abd al-Haq, and his son, Yusuf, who were working there separately. Spotting Amira, the masked men began hurling rocks at him as well. The fact that he was elderly apparently made no impression on them. According to Amira, they had large rocks that they had brought with them. Otherwise, they were not armed and did not wield clubs. He tried to evade the onslaught but could not escape. At one point, he was struck on the left side of his head, and he collapsed to the ground. He doesn’t know how long he lay there, nor does he remember any more about the person who threw the rock that hit looked like.

“They didn’t look like people to me, but devils,” he tells us now.

Soldiers appeared out of nowhere and administered first aid. His wife and the three grandchildren, also arrived, and were distraught. Blood streamed from his head, and an army paramedic stanched the wound. The soldiers summoned an Israeli ambulance to meet them at Hashmona’im. Amira managed to walk with the aid of the soldiers, but the Druze guard at the settlement’s gate refused to allow any of them to enter.

“Your dogs attacked me and you guard them and don’t let me in?” Amira said to him angrily, in Arabic.

Mohammed Abu Subheiya.Credit: Alex Levac

An IDF jeep arrived and took him to the Nili checkpoint, where he was transferred to a Palestinian ambulance and taken to the Ramallah Governmental Hospital. There Amira was stitched up and held for three days to check for possible intracranial bleeding. After he was released at the end of the week, however, he started to suffer from headaches and vomiting. He returned to the hospital this past Sunday, was checked and released again. He was still experiencing headaches and continuing to throw up this week when we visited.

Amira tells us that he feels even more determined than he did before the incident. Of course he will return to his land, there’s no question, he asserts. It’s his property, no one is going to stop him. He has already filed a complaint with the police, and handed over an Israeli ID card that his nephew found at the site of the attack. It belongs to a Y.C., born in 2003, resident of Ganei Modi’in, a neighborhood in the ultra-Orthodox settlement of Modi’in Ilit.

Trees that were cut down in Mohammed Abu Subheiya’s grove. Credit: Alex Levac

Mohammed Abu Subheiya, 63, a father of eight, is waiting next to his house in Jaba, north of Hebron. For 24 years he worked in Ashdod for Ashtrom, an Israeli construction company. Lately he’s been working in construction in Israel with other employers.

In 1990, Abu Subheiya’s father planted 22 dunams of olive trees, which Abu Subheiya tends in his spare time.

We walk with him down a precipitous, rock-strewn trail to his plot of land, which lies in the valley that runs between Jaba and the settlement of Bat Ayin, which gained notoriety in 2002 when a terrorist underground was uncovered there. Some of the settlers there are newly religious, including some from the Bratslav Hasidic sect. Bat Ayin is where the assailants of the Jaba groves come from.

Abu Subheiya hadn’t visited his grove since early March, because of the coronavirus crisis, which forced him to remain in Israel and not go back and forth to the West Bank. At the beginning of October, the International Red Cross informed him that days had been set for him to harvest the trees in his grove, which lies in a danger zone because of the Bat Ayin settlers. Arriving there on October 4, he was stunned to see that only about half of the 48 trees he has here were still intact. The assailants had gone from tree to tree and sawed off the branches or uprooted the trunks completely. It will take five years for the damaged trees to recover and bear fruit again, he tells us.

We walk from one tree to the next, examining their battered branches, and reflect on the malice of people who are capable of wreaking such destruction upon the fruit of the earth and upon those who work the land. An aroma of sage wafts from bushes along the edges of the grove. Across the way, the mobile homes of Bat Ayin are perched on the slope of a hill. Abu Subheiya says that when the settlers approach his land he flees in fear. After the incident early this month, he too filed a complaint with the police, at the station in the ultra-Orthodox settlement of Betar Ilit; some officers even came to see his grove, but since then he has heard nothing from them. Nor will he. Five years ago, settlers spread a chemical substance on the ground that poisoned 13 of his oldest trees, whose jagged trunks still stand as a silent monument in the grove.

“They work very slowly,” he says of his attackers. “That’s their politics. To destroy slowly, every time somewhere else, so we will remain without olives.”

We descend the hill on the other side of the village, opposite Betar Ilit. The road leading to the olive groves was demolished by the Israeli Civil Administration six years ago, because this is Area C (under full Israeli control). Access now is possible only in a 4×4 vehicle.

Khaled Mashalla at the improvised parking lot.Credit: Alex Levac

“Why does a road bother anyone,” asks Abu Subheiya. “You want to take our land – take it. But why does a road bother anyone? We paved an asphalt road. They came and smashed it to bits.”

We are now making our way on foot to the grove belonging to Khaled Mashalla, 69, on the lower slope of the steep valley. The remains of the ruined road are still evident under the dirt. Only the section near the village was demolished, the rest was left paved as it was.

Last week, assailants came here, too, and uprooted dozens of trees; trunks and broken branches are strewn along the way. Mashalla estimates that he lost 220 trees. He’s an amiable, colorful man who works in the improvised parking lot at the Gevaot checkpoint for Palestinian laborers who cross into Israel, Together with his business partner, he takes 7 shekels ($2) protection money per car per day to guard it against theft. Plump and gleeful, he wears a tattered felt hat that he removes in a theatrical gesture to reveal his bald head. He and his brothers own 400 dunams of olive trees in the area.

The vandalism occurred on the night between Tuesday and Wednesday of last week. The Bedouin who live on the edge of the village called Mashalla to say that they saw headlights in his grove that night. The next afternoon, when he got there after working at the checkpoint, he couldn’t believe his eyes. Dozens of branches had been sawed off. When we visit, we see that the younger trees were spared. They had been wrapped in plastic tubing, to protect them from the gazelles.