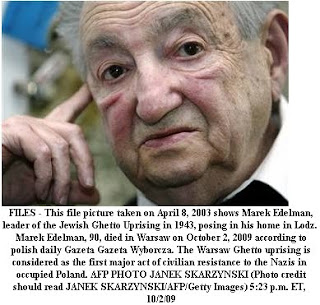

An interesting obituary for Marek Edelman in Ha’aretz by someone who is clearly a Revisionist Zionist but who nonetheless recognises the contribution of Marekt Edelman and the fact that he remained a determined opponent of Zionism to the last. Not for him the ‘negation of the Diaspora’ and other anti-Semitic notions. Tony Greenstein

Marek Edelman – The End of an Era

By Laurence Weinbaum

The death of Marek Edelman, on October 2, surely marks the end of an era. Although a handful of Warsaw Ghetto insurgents are still with us, Edelman was certainly the best known of them, and was the last surviving leader. He escaped through the sewers and returned to fight again in the abortive 1944 Warsaw Uprising. Edelman wrote one of the first accounts of the struggle of his comrades in the ghetto. Characterizing the Jewish resistance there, he said: “We fought simply not to allow the Germans alone to pick the time and place of our deaths.“

After the war, he settled in Lodz and studied medicine, determined to play a part in the building of a new Poland founded on socialist principles, in which Jews would enjoy civil rights and cultural autonomy. This was, of course, not to be. For Edelman, like others, Jews and non-Jews alike, who genuinely believed in the socialist cause and in human rights, the so-called “People’s Poland” proved a great disappointment. Over successive years, many voiced that disillusionment with their feet by leaving the country.

But Edelman remained in Poland, even when his immediate family chose to leave. “After all, someone has to stay here with all those who perished here,” he repeatedly declared.

One can decry that stubbornness or admire it, but there is no denying that in electing to live in Poland, he became a thorn in the side of the communist regime – and a symbol of the Polish-Jewish symbiosis that many believed had perished in the gas chambers of Treblinka and, immediately following the war, in the bloodstained streets of Kielce.

True to his Bundist roots, Edelman never made his peace with Zionism, and was often a bitter, even vitriolic, critic of the Jewish state and its policies. In August 2002, he wrote a letter in support of those whom he called “commanders of the Palestinian military, paramilitary and partisan operations – to all the soldiers of the Palestinian fighting organizations.” Although condemning the wave of suicide bombings that wracked Israel at the time, Edelman expressed solidarity with the Palestinian struggle. In so doing, the ghetto veteran furnished advocates of the Arab case with potent ammunition.

Edelman’s disenchantment with Israel arose out of his own sense of humanism. Above all, it was rooted in his belief in an ideology that has been relegated to the dustbin of history. Edelman was probably the last representative of a once-flourishing movement in Poland and throughout East Central Europe that believed in doikeit (Yiddish for “hereness”). Bundism rejected the idea that Jews should pick up and leave their native lands.

While neither religiously observant nor a Zionist, Edelman was a passionate Jew. Had he succumbed to the fleshpots of New York, Paris or Melbourne, perhaps his former ghetto comrades now living on kibbutz could have forgiven him. It was his decision to remain in the dilapidated city of Lodz, the former epicenter of the Shoah, that seemed so objectionable and even offensive – and an inexplicable, yet powerful negation of Zionist triumphalism.

Upon hearing of Edelman’s death, Tadeusz Pieronek, a Polish bishop known for his liberal views opined, “I respect him mostly for the fact that he stayed in this land, which made him fight so hard for his Jewish and Polish identity … He became a real witness; he was giving real testimony with his life.” Like many witnesses asked to describe events in which they had taken part, Edelman was an imperfect source of information. At times, his undisguised and intemperate distaste for his Jewish political rivals tainted the veracity of his testimony.

After the war, perhaps Edelman’s “finest hour” was in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, when he joined the precursor of Solidarity and later the mass movement itself. During that time, he displayed courage and outspokenness in the face of the repressive policies of the Communist regime. He was even once briefly subjected to house arrest.

In 1983 he was invited to take part in a showcase ceremony to mark the 40th anniversary of the ghetto uprising. He refused to participate in what he saw as a shameless and transparent attempt by Communist authorities to deflect international attention from its attempt to stifle opposition. To appear at the event, he claimed, “would be an act of cynicism and contempt” in a country “where social life is dominated throughout by humiliation and coercion.”

Edelman did, however, take part in the 1989 Round Table Talks that led to democratic rule and genuine national rebirth, and was elected to the Polish parliament, the Sejm.

Writing in Haaretz earlier this week, Moshe Arens, one of the commanding personages of the Revisionist Movement – for which Edelman, it must be said, had nothing but contempt – described his own failed attempts to secure an honorary degree for Edelman. “I ran into stubborn opposition … in Israel. He had received Poland’s highest honor, and at the 65th commemoration of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising he was awarded the French Legion of Honor medal. He died not having received the recognition from Israel that he so richly deserved.”

Perhaps that graceful and generous display of recognition by one octogenarian for another, though on the opposite side of the political fence, is a most fitting obituary for the complicated and cantankerous Polish cardiologist and ghetto fighter – and the best testimony to his greatness.

Dr. Laurence Weinbaum is chief editor of the Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, and co-author of a forthcoming book on the Jewish Military Union (ZZW) in the Warsaw Ghetto.