|

| Babi Yar – the ravine where over 30,000 Jews were murdered |

|

| Babi Yar |

|

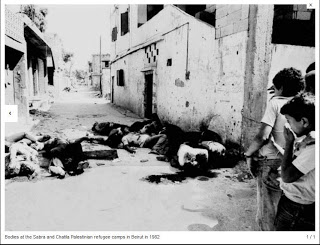

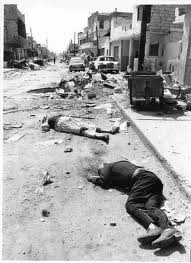

| the handiwork of Israel’s Phalangist allies |

Sabra & Chatilla – A Massacre from the Annals of Nazi and Fascist Barbarity

To those who say that at least Israel hasn’t opened up extermination camps for the Palestinians one must agree. It is however one of the few things they haven’t done. Sabra and Chatilla, a refugee camp in Beirut where some two thousand defenceless Palestinian refugees were murdered by fascist savages, with knives and guns, who committed the most unspeakable horrors, including castrating young boys, stands as a testament to Israeli civilisation. That the author of this massacre, Ariel Sharon, was forced to resign as Defence Minister and came back as Prime Minister is no shock.

It was the share policy of both the ‘socialist’ Zionists and Likud to form an alliance with the Phalangists, the party that was formed by an open admirer of Hitler Pierre Gemayel and named after Franco’s party of the same name (but different spelling).

Israel provided the cover and flares for the Phalangist murderers, having first secured the exist of the PLO fighters. One more crime of Yasser Arafat was abandoning his people to the tender mercies of the Zionists and therefore leaving those in the camps vulnerable to just such retribution, though even Arafat couldn’t have imagined just what would take place once Israel had entered Beirut.

Below is an account by an Israeli member of the Merkava tank batallion of just what happened in Sabra and Chatilla

Tony Greenstein

Thirty years since the massacre in Sabra and Shatila – a personal testimony

Translation from Hebrew: by Sol Salbe on Sunday, 23 September 2012 at 02:27 ·

[From the Marker Cafe section of the Haaretz Hebrew website]

Thirty years since the massacre in Sabra and Shatila – a personal testimony

For thirty years “S” ran around with this story inside him but he did not share it with a soul. He even refused to cooperate with the researchers for the film Waltz with Bashir, who mange to locate him in his current country of residence. When they told him that his friends had all given their account and mentioned his name, he said that he did not remember anything. He just did not want to talk about it, he felt that he did not have the strength to deal with the memory and did not see the film.

During the last Rosh Hashanah [Jewish New Year, 16-18 Sep 2012 -tr] he had a conversation with his wife about the holiday’s customs. The apple and honey, for a sweet new year, stirred the memory and then the dam broke loose and he told her everything. After that he found the courage to re-enact the whole scene in his mind and share it with some friends, myself included [The person who took it toThe Marker blog.] He wanted to publish it anonymously, “Maybe the virtual anonymity would hide the stain in my soul …”

S was a soldier in armoured corps. He was 19, a former yeshiva [Jewish seminary]student who left the yeshiva and gave up religion a few months before he was called up. The Sabra and Shatila massacre “gave me shell shock, resulting eventually in the end the army throwing me away from its ranks and my discharge,” he says today.

It was Friday afternoon. My company’s tanks from the Merkava tank battalion, which is based not far from Jericho, sat on a dirt road that surrounded Beirut Airport. An army truck delivered us the provisions for the holiday including honey, eggs and all kinds of products that we bartered with locals for quality hash. We used Israeli money in the supermarket to buy 7UP which wasn’t available in Israel, and lollies and Kent cigarettes which were all much cheaper than back home.

Bashir Gemayel had been assassinated two days earlier and we were told that we were being transferred to another sector. We had to drive the tanks because there was no time to bring the tank transporters. We also got told that in the high rise buildings nearby there were Palestinians on the verandas who fired on military vehicles travelling along the road.

Our tank mounted a small hill on the dirt track next to the field and all the provisions that we had stacked in the turret’s basket crashed onto the tank interior. The contents of the egg cartons and jars of honey stained our clothes but we had no time to change our uniforms because we were moving. About two hours later we reached the fence. It was a stone wall three metre high. The commanders were several hundred metres away on the fifth floor of an abandoned building. All the officers were there observing the camp.

An hour or two later, 70 Phalangist troops arrived. They wore smart ironed uniforms and shiny shoes. They had Israeli Galil rifles and brand new combat vests to make us enviable. We had the shortened version of the Galil and shrivelled vests. They were in groups of three, stamping their feet on the ground in some sort of a drill, while their commander was talking with a brigade, or a division, commander who was at the fifth floor vantage point.

It was getting dark and we continued to wait for instructions as to what to do. Those who needed to pee had to use the Merkava’s back door of the carriage. Everything in the tank had been closed in case some Palestinian sniper took a shot at us over the fence. Half an hour later an Israeli bulldozer turned up from somewhere. Our tanks were adjacent to the wall and we had to move them to give access to bulldozer. We were two Merkava tanks and a paratroopers’ halftrack which was parked next to us.

The Phalangists continued with their drills in groups of three while the bulldozer opened gaping hole in the wall. We could only see them through the tank’s periscope, we could not hear them. We left the back door of the tank open as it was pretty stifling with all the eggs, chalot and honey that were strewn all over the floor. Each step we took inside the tank seemed as though we were treading in mud, with yet another egg shell crashed.

After the bulldozer choofed off all the Phalangists lined up in threes for yet another series of drills. Then they entered the camp. We stayed in the tanks. Their commander asked our commander to fire flares over the camp because it was getting dark. Through the back door we started hearing gunshots and lots of screams, especially women’s, the crying of children, and in general lots of screaming.

Throughout the night, about every quarter of an hour, the APC next to us fired flares over the camp. The descended slowly in a blinding light, being slowed down by a small parachute. They put out a huge amount of light. When went out they fired the next one.

Not much happened among us, between one flare and another we fell asleep with our clothes still dribbling with honey and eggs. The tank driver fell asleep on his seat, the gun loader slept under the barrel, the commander crawled towards the back door and fell asleep on the tank’s floor, I was a gunner and I slept in my seat with my head resting on the gun’s sight. It bent my glasses and they felt weird.

In the morning we woke up and went outside. there was screaming coming in from all directions. We climbed on top of the tank and saw beyond the wall. At the doorways to the homes their there were all sorts of bodies lying at odd angles. Other soldiers began to yell and we talked among ourselves that they are killing everyone there and what are we meant to do …

Our company commander, a pilot course dropout who was totally immersed in daydreams, had no clue as to was happening around him. He went to talk to the commanders situated on the fifth floor. He came back and said that they can see it all and it’s not our role to interfere. It’s a local conflict between the Phalangists and the Palestinians. And in any case they have been reporting what they saw to the senior officers. And at that point there no instruction to take action. So we so we are to sit tight until we get an order.

It was noon and we started to clean and wash the tank. We washed some of our undershirts and hung them on a makeshift rope tied between two tanks. We had quite a lot of water in containers. The shouting and screaming from over the wall went on with us not knowing what to do.

Waiting for orders …

At lunch I heard my friend Oren. He stood on his tank and peered over the fence and yelled at the fifth floor, “It’s a massacre. They are killing everyone there.”

Still we received no instructions.

Then a young man escaped through a hole in the wall. He was about twenty years old, he seemed slightly older than me – I was 19. He was followed by a Phalangist replete with a new Galil and a new vest. The fellow stood behind me and grabbed me by the shoulders. He was barefoot, wearing shorts and an old torn singlet. He smelt of fear, a smell which was really repulsive and nauseating, something like a combination of vomit and stale sweat. He spoke to me and wept that the Phalangist wants to kill him and asked me for help. He yelled in English HELP HELP, and in Arabic, he murmured that the Phalangist has killed them all and now he wants to kill him and I should save him. I embarrassingly looked at the commander and asked him what to do. He smiled and winked at me and said, “Let them do the dirty work,” and signalled the Phalangist that he can drag the crying Palestinian from behind me. He grabbed the fellow by the scuff of his neck and took him for three-four steps. The youth continued to plead and looked at me and the Phalangist and begged us to take pity on him. The Phalangist shot him in the knee. The Palestinian began to scream in pain and dropped to his knees and screamed at us for help. The Phalangist shot another bullet in his abdomen and when he collapsed in front of him on the ground, his head almost touching the Phalangist’s shoes, he fired m another shot in his head and then everything went quiet.

I looked at it in shock. This was the first time I saw death so close-up. The Phalangist disappeared over the wall and back into the refugee camp.

Mercedes cars with press credentials began to arrive. Our commander declared that the area was a closed military zone and it is not open to anyone. I heard them arguing in Hebrew. It was a reporter for Time magazine. He said that they have gathered them all, children, the elderly and women, in a soccer field and were shooting them row by row and we ought to do something.

A commander from the fifth floor came down and started yelling at the reporter not to tell him what to do and it’s a military zone and that he should not be here. The reporter yelled back at him, that he has come over just now from the other side of the camp and on the other side let them come in, and everything was covered in blood and it was just horrible what was happening there.

We also began to uneasily ask uneasily what are we to do and what is going on and who are we waiting for . He said it was a holiday now and that the Chief of Staff, Rafael Eitan, with in contact with Prime Minister Begin by phone. And perhaps because of the New year holy day he didn’t to talk to Begin by phone so for time being there is no ruling and no instructions.

Again someone came in a Red Cross car and complained to the commander from the fifth floor that the Phalangists were shooting at everyone and not letting the Red Cross take care of the wounded. The commander said he had passes the information on and once a decision has been arrived at we would receive an order to move in. In the meantime it’s a Lebanese internal conflict.

Just before the following evening(!) We got told to go in. Most of the Phalangists had already left. We were told to park our tanks in front of one of the buildings there. Someone in a suit came to speak to the commander from the fifth floor. They told us that there was a Mossad agent in the camp and he will give us the signal.

We entered and in every doorway there were bodies, with dripping blood on the stairways. There was a terrible stench of corpses and fermenting blood. We went up to the first floor. The doors were open and every room there were bodies. There were bodies on the beds, on the floor and down the hallways. The corpses were on their back with bullet holes. Women with children and babies leaning on the doors. Every single one of them was dead. Some of the bodies seemed as if they were stabbed with a knife like a sword. Women bereft of clothing or with their dresses half torn, lying on the back with a bullet in the head.

We could not stay there and we went back to the tank. After dark we saw a flashing sign from one of the windows of the basement in the building opposite our parking spot. We passed the message on that we have seen the signal. Along came a jeep. A man got out of the building, hopped into the jeep and they drove off.

The next morning, the whole area was full of journalists. The smell was unbearable, and everywhere there were journalists and radio reporters speaking into their microphone. They sent us to the soccer field. There were rows upon rows of bodies wrapped and covered with blankets and rags. An army tractor dug a trench, shoved the bodies into it and covered them with dirt.

It reminded me of pictures of the Babi Yar massacre at Yad Vashem [Holocaust museum.]

And I do not remember anymore. The timing is all mixed up.

I was nauseous and vomited repeatedly. I wanted to go home and cried like a little kid.

They sent me home. Another friend of mine and I were taken by jeep to Rosh Hanikra [Lebanon-Israel border]. From there we hitched a ride to Nahariya. I do not remember anything from that time. We made it to Jerusalem after a drive of more than ten hours.

I went to my mother’s house. I thought that she would be happy to see that I was alive and did not die in the war. I sat there in the kitchen. She sat across from me and said nothing, like asking what I want and what I came for. After a few minutes of silence she asked me if I wanted a drink, and brought me some tap water in a disposable glass. I sat there for a few minutes more I did not know what to tell her and she looks at me and still did not know what she was meant to do. I really wanted her to hug me – perhaps the only time in my life I really wanted someone to hug me. After another fifteen minutes of silence I left her home and went to my sister’s place. My sister gave me new clothes and laundered my uniform.

I don’t know how long I slept. At night I had a nightmares and I could not close my eyes without seeing bodies fall on me. When I did fall asleep I dreamt that the pillow was a dead man whom I was lying on top of, and I got up sweating and screaming. Only during the day I managed to get some sleep with the window open. In the shade and darkness I just felt scared and sweating and could not sleep. I kept on vomiting and lost weight.

I had a friend in basic training who after basic training left the armoured corps and was transferred to Jerusalem. He told me that every time I come to Jerusalem to I should call him so we go out and talk. I called him. We met and he said that he had a nice sister whom he wanted me meet and invited me to his home for Shabbat.

During the day, I managed to function somehow but once I put on the uniform I began to sweat and get nauseous and vomit.

About two weeks later my commander managed to track me down at my sister’s. He convinced me to go back with him and that everything would be fine. I rode in his jeep from Jerusalem to Rosh Hanikra. Once we got to the border I got a bit of a shock, got out of the vehicle and started walking back to whence I came from. I did not want to talk to anyone, just wanted to cry and to be left alone. I screamed at anyone who came near me that I’d shoot them and shoot myself and I just wanted to be left alone.

Somehow I remember being in Jerusalem again my sister’s house. At the end of the week I went to my friend Tamir’s place. The food was really tasty and his sister never related to me the whole time I was there. She just totally ignored my presence. At night everyone went to bed and I stayed awake in bed. I slept on a mattress next to the kitchen, there was light from the moon and could not sleep.

Later – around 2am – his mother came into my bed naked. I will not go into embarrassing details but I was her gigolo for the next three years. After three months the military police tracked me down me and arrested me for desertion. They sent me to jail. I wanted to commit suicide but took my shoelaces and there was no way to commit suicide. After a few days in jail I was sent to trial. The judge asked me why I ran away I started crying, I started telling him about everything since Sabra and Shatila. He released me from prison immediately and instructed me to meet Mental Health Officer.

I went back to that woman’s house. Every few days I had to go for observations. They admitted me to the mental health unit for a week or so. They thought that I may try to kill myself. Again I went to the woman’s place for sex therapy. Again I went to the Mental Health Officer and then I again went back to her house for a month or two.

I slept during the day, and at night I wrote I kept losing weight and vomiting. From time to time I had nightmares but slowly, slowly they disappeared, especially when I slept on. If I woke up and saw the light of day, I could sleep again. If it was dark I would begin to see the dead walking around. All the bodies that were wrapped in rags would begin to move or jump. Suddenly I would wake up screaming and sweating. But if it was daylight I could fall asleep without a problem. The food at this woman’s place was excellent and I spent a good long time there. Her daughter found another boyfriend and left the house. Tamir was discharged from the army and emigrated to the United States. I remained with this woman.

After a few more weeks and meetings with the Mental Health Officer, I got told if I wanted to be discharged I would need to sign a form stating I can make no claims upon the army now or in the future. I was happy to sign and receive the discharge papers.

I did not give evidence to the Kahan Commission of Inquiry [into the Sabra and Shatila massacre]. For starters I was a deserter and then they probably thought I was crazy anyway, and my opinion did not count …

Not long after that I emigrated and I have been living abroad since 1988. I felt disappointed with way the army treats its own victims. I joined the army with Medical Profile 89 [Close to highest] and was discharged with Medical Profile 21 [Totally disabled]. In other words the change in my Medical Profile while I was in the care of the army, but they made me sign a form that I make no claims upon the army and made my release conditional on the signing of an illegal document, especially considering my poor mental state at the time. I’m happy I came out alive. But I’m sorry for all the soldiers – some of whom were my friends – who were killed in a senseless war.

Hebrew original:

Translated by Sol Salbe of the Middle East News Service –

The forgotten massacre

30 years after 1,700 Palestinians were killed at the Sabra and Chatila refugee camps, Robert Fisk revisits the killing fields

The memories remain, of course. The man who lost his family in an earlier massacre, only to watch the young men of Chatila lined up after the new killings and marched off to death. But – like the muck piled on the garbage tip amid the concrete hovels – the stench of injustice still pervades the camps where 1,700 Palestinians were butchered 30 years ago next week. No-one was tried and sentenced for a slaughter, which even an Israeli writer at the time compared to the killing of Yugoslavs by Nazi sympathisers in the Second World War. Sabra and Chatila are a memorial to criminals who evaded responsibility, who got away with it.

Khaled Abu Noor was in his teens, a would-be militiaman who had left the camp for the mountains before Israel’s Phalangist allies entered Sabra and Chatila. Did this give him a guilty conscience, that he was not there to fight the rapists and murderers? “What we all feel today is depression,” he said. “We demanded justice, international trials – but there was nothing. Not a single person was held responsible. No-one was put before justice. And so we had to suffer in the 1986 camps war (at the hands of Shia Lebanese) and so the Israelis could slaughter so many Palestinians in the 2008-9 Gaza war. If there had been trials for what happened here 30 years ago, the Gaza killings would not have happened.”

He has a point, of course. While presidents and prime ministers have lined up in Manhattan to mourn the dead of the 2001 international crimes against humanity at the World Trade Centre, not a single Western leader has dared to visit the dank and grubby Sabra and Chatila mass graves, shaded by a few scruffy trees and faded photographs of the dead. Nor, let it be said – in 30 years – has a single Arab leader bothered to visit the last resting place of at least 600 of the 1,700 victims. Arab potentates bleed in their hearts for the Palestinians but an airfare to Beirut might be a bit much these days – and which of them would want to offend the Israelis or the Americans?

It is an irony – but an important one, nonetheless – that the only nation to hold a serious official enquiry into the massacre, albeit flawed, was Israel. The Israeli army sent the killers into the camps and then watched – and did nothing – while the atrocity took place. A certain Israeli Lieutenant Avi Grabowsky gave the most telling evidence of this. The Kahan Commission held the then defence minister Ariel Sharon personally responsible, since he sent the ruthless anti-Palestinian Phalangists into the camps to “flush out terrorists” – “terrorists” who turned out to be as non-existent as Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction 21 years later.

Sharon lost his job but later became prime minister, until broken by a stroke which he survived – but which took from him even the power of speech. Elie Hobeika, the Lebanese Christian militia leader who led his murderers into the camp – after Sharon had told the Phalange that Palestinians had just assassinated their leader, Bashir Gemayel – was murdered years later in east Beirut. His enemies claimed the Syrians killed him, his friends blamed the Israelis; Hobeika, who had “gone across” to the Syrians, had just announced he would “tell all” about the Sabra and Chatila atrocity at a Belgian court, which wished to try Sharon.

Of course, those of us who entered the camps on the third and final day of the massacre – 18 September, 1982 – have our own memories. I recall the old man in pyjamas lying on his back on the main street with his innocent walking stick beside him, the two women and a baby shot next to a dead horse, the private house in which I sheltered from the killers with my colleague Loren Jenkins of The Washington Post – only to find a dead young woman lying in the courtyard beside us. Some of the women had been raped before their killing. The armies of flies, the smell of decomposition. These things one remembers.

Abu Maher is 65 – like Khaled Abu Noor, his family originally fled their homes in Safad in present-day Israel – and stayed in the camp throughout the massacre, at first disbelieving the women and children who urged him to run from his home. “A woman neighbour started screaming and I looked out and saw her shot dead and her daughter tried to run away and the killers chased her, saying “Kill her, kill her, don’t let her go!” She shouted to me and I could do nothing. But she escaped.”

Repeated trips back to the camp, year after year, have built up a narrative of astonishing detail. Investigations by Karsten Tveit of Norwegian radio and myself proved that many men, seen by Abu Maher being marched away alive after the initial massacre, were later handed by the Israelis back to the Phalangist killers – who held them prisoner for days in eastern Beirut and then, when they could not swap them for Christian hostages, executed them at mass graves.

And the arguments in favour of forgetfulness have been cruelly deployed. Why remember a few hundred Palestinians slaughtered when 25,000 have been killed in Syria in 19 months?

Supporters of Israel and critics of the Muslim world have written to me in the last couple of years, abusing me for referring repeatedly to the Sabra and Chatila massacre, as if my own eye-witness account of this atrocity has – like a war criminal – a statute of limitations. Given these reports of mine (compared to my accounts of Turkish oppression) one reader has written to me that “I would conclude that, in this case (Sabra and Chatila), you have an anti-Israeli bias. This is based solely on the disproportionate number of references you make to this atrocity…”

But can one make too many? Dr Bayan al-Hout, widow of the PLO’s former ambassador to Beirut, has written the most authoritative and detailed account of the Sabra and Chatila war crimes – for that is what they were – and concludes that in the years that followed, people feared to recall the event. “Then international groups started talking and enquiring. We must remember that all of us are responsible for what happened. And the victims are still scarred by these events – even those who are unborn will be scarred – and they need love.” In the conclusion to her book, Dr al-Hout asks some difficult – indeed, dangerous – questions: “Were the perpetrators the only ones responsible? Were the people who committed the crimes the only criminals? Were even those who issued the orders solely responsible? Who in truth is responsible?”

In other words, doesn’t Lebanon bear responsibility with the Phalangist Lebanese, Israel with the Israeli army, the West with its Israeli ally, the Arabs with their American ally? Dr al-Hout ends her investigation with a quotation from Rabbi Abraham Heschel who raged against the Vietnam war. “In a free society,” the Rabbi said, “some are guilty, but all are responsible.”

Timeline: Sabra and Chatila

14 September 1982

Lebanon’s Christian President-elect, Bashir Gemayel, is assassinated by a pro-Syrian militant but his loyalists blame the Palestinians.

16 September 1982

Lebanese Christian militiamen enter camps at Sabra and Chatila to carry out revenge attacks on Palestinian refugees, with occupying Israeli forces guarding the camps and firing flares to aid the attacks at night.

18 September 1982

After three days of rape, fighting and brutal executions, militias finally leave the camps with 1,700 dead.

Rob Hastings