You will no doubt be familiar with the familiar ‘security’ argument for ethnic cleansing and expulsions. It goes something like this.

You will no doubt be familiar with the familiar ‘security’ argument for ethnic cleansing and expulsions. It goes something like this.

First we give them a hard time, discriminate as a matter of course, pay less, impose different restrictions etc., then when they rebel and if, god forbid, they use violence, then we can describe them as terrorists. Mind, dear reader, I know what’s going through your head. But Israel uses violence all the time. How childish – the violence of the state never counts. It is only the violence of the oppressed that matters.

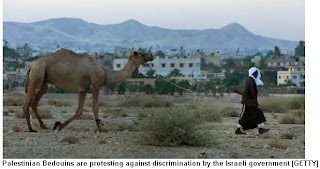

The problem of the Bedouin is that they have been very quiet, they haven’t resorted to violence etc. But that’s not a problem because it means they get little publicity and therefore Israel can expel, move, uproot them when they want.

Below are 2 articles on the Bedouin from different writers. It should be borne in mind that the Jewish National Fund, the Zionist entity which owns 13% and controls 93% of Israeli land, has been in the forefront of the ethnic cleansing of the Bedouin in the Negev and Israeli Arabs in the Galilee. This is the ‘charity’ that David Cameron and Gordon Brown were patrons of.

Tony Greenstein

Israel’s Negev ‘frontier’ By Ben White

On this year’s Land Day, tens of thousands of Palestinian citizens of Israel marched in Sakhnin, an Israeli city in the Lower Galilee, to protest against past and present systematic discrimination. But with the focus on Israel’s policies of land confiscation, there was significance in a second protest that day.

In the Negev (referred to as al-Naqab by Palestinian Bedouins), over 3,000 attended a rally at al-Araqib, an ‘unrecognised’ Palestinian Bedouin village whose lands are being targeted by the familiar partnership of the Israeli state and the Jewish National Fund.

The historical context for the crisis facing Palestinian Bedouins today is important, as the Israeli government and Zionist groups try to propagate the idea that the problems, so far as they exist, are ‘humanitarian’ or ‘cultural’.

Even the category of ‘Bedouin’ is historically and politically loaded, with many disputing what they see as an Israeli ‘divide and rule’ strategy towards the Palestinians.

Alienated and ‘unrecognised’

During the Nakba, the vast majority of the Palestinian Bedouins in the Negev – from a pre-1948 population of 65,000 to 100,000 – were expelled. Those who remained were forcibly concentrated by the Israeli military in an area known as the ‘siyag’ (closure).

The military regime experienced by Palestinian citizens until 1966 meant further piecemeal expulsions, expropriation of land, and restrictions on movement. Ultimately, only 19 out of 95 tribes remained. The defining dynamic between the Israeli state and its Palestinian minority has been the expropriation of Arab land and its transfer to state or Jewish ownership.

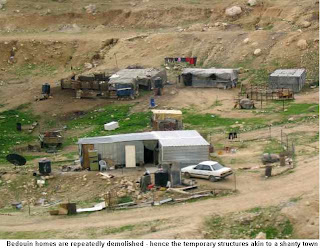

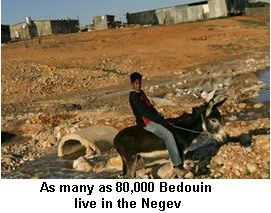

Israel refused to recognise the land rights of the Palestinian Bedouins, who today are alienated from almost all of their land through a complex combination of land law and planning boundaries. An estimated 70,000 to 80,000 Palestinian citizens in the Negev live in dozens of ‘unrecognised villages’ – communities that the state refuse to acknowledge exist despite the fact that some pre-date the establishment of Israel and others are the result of the Israeli military’s forced relocation drives.

These shanty towns are refused access to basic infrastructure. One approach the Israeli state has taken is to create, or ‘legalise’, a small number of towns and villages in the hope that more Palestinians will move into these areas.

Yet even this policy, often presented as a ‘humane’ response to ‘Bedouin’ needs, highlights a disparity: Jewish regional authorities and individual farms enjoy a massively lower population density compared to the space allotted by the state to Palestinian townships, which are ranked among the most deprived communities in the country.

‘Developing the Negev’

The Israeli government, meanwhile, along with agencies like the Jewish National Fund and Jewish Agency, are preoccupied with the idea of ‘developing the Negev’, and boosting its population.

In March, the ‘Negev 2010′ conference was held in Beir al-Saba’ (Beersheva), drawing hundreds of politicians and business people, with the focus being attracting 300,000 new residents to the area.

Speakers included Shimon Peres, the Israeli president, Silvan Shalom, the Negev and Galilee development minister, and Ariel Atias, the housing minister.

Last year, Shalom held a joint press conference with religious Zionist rabbis to outline plans for increasing the south’s population, with one of the rabbis stressing the need for a “Jewish majority” in the region.

Atias, for his part, has previously expressed his belief that it is “a national duty to prevent the spread” of Palestinian citizens. It is not, therefore, hard to read between the lines when Israeli policy makers and Zionist officials from organisations like the Jewish National Fund talk about ‘developing the Negev’.

Zionist frontier

The Negev is the location for classic, unfiltered Zionist frontier discourse.

The Jewish National Fund in the UK talks about supporting “the pioneers who are bringing the desert to life”, while an article in the Zionist magazine B’Nai B’Rith called the Negev “the closest thing to the tabula rasa many of Israel’s pre-state pioneers found when they first came to the Holy Land”. The idea of the ’empty’ land sits uncomfortably alongside another important emphasis – ‘protection’ or ‘redemption’.

As the Jewish National Fund’s US chief executive put it in January 2009, “if we don’t get 500,000 people to move to the Negev in the next five years, we’re going to lose it”. To who, he did not need to say. There were no illusions about the meaning of this discourse, and its consequences, at a February conference which brought together academics and experts specialising in issues facing the Bedouins of the Negev.

Through the seminars and discussions, one theme clearly came through: The relationship between the Palestinian Bedouins and the Israeli state was rapidly deteriorating. A number of the organisers of, and speakers at, ‘Rethinking the Paradigms: Negev Bedouin Research 2000+’ were themselves from the Negev, where overcrowding, home demolitions, and dispossession are features of everyday life for Palestinians. The conference was one of the first of its kind in the UK, sponsored by the British Academy and Exeter University’s Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies and Politics Department.

Excluded from discourse

Western media coverage of the structural discrimination and discriminatory land and housing policies experienced by Palestinian Bedouins has generally been poor.

In a discourse shaped by Zionist and Orientalist tropes, the Negev is a vast, wild, desert; a frontier to be civilised. The ‘Bedouin’, meanwhile, are either invisible or exotic savages, objects of benevolent philanthropy.

Furthermore, the international ‘peace process’ has meant that the question of Palestine has become the story of negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. Palestinian citizens of Israel have been left out, a situation exacerbated by the media mentality of ‘if it bleeds it leads’. Core issues facing Palestinian Bedouins – land control, zoning, bureaucratic and physical boundaries of exclusion – are not considered suitable fare.

This nonexistent or weak coverage is regrettable, particularly as Israel’s policies in the Negev towards the Palestinian Bedouin minority are highly illuminating for understanding the state’s position vis-à-vis the Palestinians in a more general sense.

Moreover, tension is building in the Negev over Israel’s continued apartheid-like policies. Palestinian Bedouins continue to resist the strategies of the Israeli state and Zionist agencies, through legal battles, and grassroots organisation, like the Regional Council for the Unrecognised Villages.

Perhaps one of the main kinds of resistance being offered by the Palestinians in the Negev is their determination to stay. This steadfastness is a direct refusal of a strategy of home demolitions, dispossession and Judaisation.

The recent protest in al-Araqib could only be a foretaste of things to come, as Palestinian Bedouins demand equality from a state seemingly unwilling to change.

Ben White is a freelance journalist and writer specialising in Palestine/Israel. His articles have appeared in publications like the Guardian’s ‘Comment is free’, New Statesman, Electronic Intifada, Middle East International, Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, and others. His first book, Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide, was published in 2009 by Pluto Press.

Israeli Activist On Trial For Supporting Bedouin

A thank you from Yeela Raanan of the RCUV (Regional Council of Unrecognized Villages.)

I was taken to court yesterday for sitting in a home in an unrecognized Bedouin village, as the bulldozer was at the wall – ready to demolish the house. The police carried me out of the home and arrested me, and a couple of years later – I was put on trial for “disrupting a policeman”.

We gathered – about 40 of us, half an hour before the trial time. We sat outside the courthouse: we were Jews and Arabs – this battle was not a battle of Jews against Arabs – but all of us against powerful injustice.

In the courthouse I sat on the seat designated for the accused. All seats in the room were occupied: my colleagues, my fellow human rights activists, leaders from the Bedouin community, and the man whose house had been demolished that day – all were there with me. Lawyer Gabi Laski presented preliminary pleas: “defense for justice”: How can the Government of Israel both claim that the Bedouins are not trespassers, and that the gov’t must recognize the villages, and at the same time demolish homes?! The statistics are that one in twelve families in the Bedouin community experiences a home demolition… And – how can the Knesset pass a law that pardons the people who acted in opposition to the evacuation from Gush Katif (a settlement in Gaza), on the basis that this evacuation was traumatic, but on the other hand, these home demolitions have been traumatic for the last 60 years, and still the government takes me to trial?

Lawyer Laski’s words, describing vividly the brutality in the policies against the Bedouin, bestowed dignity to the situation. Looking at my friends and partners to my way I felt as if they were silently crying out, “We are all with you on that seat. Laski is representing all of us. The Judge will be judging us all.”

Thanks to all of you: you who sent words of encouragement, you who are sharing the financial burden, to all of you who came… it made the situation one of shared burden and responsibility. I did not feel at all alone. I, and I believe all of us, came out much stronger from this attempt of the government to break our spirit.

The judge, Judge George Amorai, seems interested in the defense line that Laski is presenting. Both sides were requested to give in their arguments in writing and the next court hearing will be on Thursday, September 16th.

Two hours before my court hearing Nuri el-Uqbi stood trial for scores of bogus accusations by the police. The judge ruled against all of the bogus accusations.