I came across this article recently and decided to republish it. A legend has grown up that the only massacre during Israel’s War of Independence, the Naqba, was that of Deir Yassin, for which Ben-Gurion apologised whilst blaming on Menachem Begin.

In fact Deir Yassin was one of a number of massacres, such as Duweimah, Tantura, Saf Saf, Lydda-Ramleh and not the largest massacre either.

Tony Greenstein

The Massacres of 1948

Not Only Deir Yassin

By Guy Erlich, Ha’ir, 6 May 1992

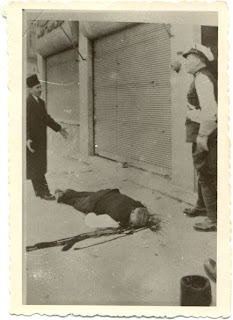

After Lydda gave up the fight, a group of stubborn Arab fighters barricaded themselves in the small mosque. The commander of the Palmach’s 3rd Battalion, Moshe Kalman, gave an order to fire a number of blasts towards the mosque. The soldiers who forced their way into the mosque were surprised to find no resistance. On the walls of the mosque they found the remains of the Arab fighters. A group of between twenty to fifty Arab inhabitants was brought to clean up the mosque and bury the remains. After they finished their work, they were also shot into the graves they dug.

The Jewish American journalist Dan Kurtzman, heard this testimony from Moshe Kalman, who has meanwhile died, while he was writing his book ‘In the Beginning 1948 (Bereshit 1948)’ about the War of Independence. As Kurtzman did not want to hurt the State of Israel, he did not include this testimony, but told this story to Israeli historian Aryeh Yitzhaki, when they met in the IDF archives, when Kurtzman was there working on his book. Kurtzman, who is now visiting Israel in connection with his new book (incidentally, these days a new edition of his older book is coming out), confirmed – after some hesitation – that he heard this testimony from Moshe Kalman.

Since its establishment, the State of Israel keeps a conspiracy of silence concerning massacres committed in the War of Independence. The only massacre acknowledged in official publications is that of Deir Yassin, perhaps because it was perpetrated by the IZL (Irgun). Books and press reports have referred to dozens of cases, but only partially and incompletely. Yitzhaki corroborates this impression: ‘I read all the documents in the IDF archives written about the War of Independence. In the course of years I became especially alert to anything concerning the massacres.’ Yitzhaki is a lecturer in the Bar Ilan University [Tel Aviv] in the Faculty of Eretz Yisrael Studies and is also senior lecturer in the field of military history in IDF courses for officers. In the sixties he served as director of the IDF archives within the framework of his IDF service in his capacity as historian.

Yitzhaki assembled all the testimonies and documents concerning the subject matter and waited for the right time to publish. “The time has come,” he says, “for a generation has passed, and it is now possible to face the ocean of lies in which we were brought up. In almost every conquered village in the War of Independence, acts were committed, which are defined as war crimes, such as indiscriminate killings, massacres and rapes. I believe that such things end by surfacing. The only question is how to face such evidence.”

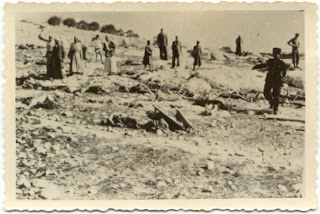

According to Yitzhaki, about ten major massacres were committed in the course of the War of Independence (i.e. more than fifty victims in each massacre) and about hundred smaller massacres (of individuals or small groups). According to him, these massacres had an enormous impact on the Arab population, by inducing their (departure) from the country.

Yitzhaki: “For many Israelis it was easier to find consolation in the lie, that the Arabs left the country under orders from their leaders. This is an absolute fabrication. The fundamental cause of their flight was their fear from Israeli retribution and this fear was not at all imaginary. From almost each report in the IDF archives concerning the conquest of Arab villages between May and July 1948 – when clashes with Arab villagers were the fiercest – a smell of massacre emanates. Sometimes the report tells about blatant massacres which were committed after the battle, sometimes the massacres are committed in the heat of battle and while the villages are “cleansed.” Some of my colleagues, such as Me’ir Pa’il, don’t consider such acts as massacres. In my opinion there is no other term for such acts than massacres. This was at the time the rule of the game. It was a dirty war on both sides. This phenomenon spread out in the field; there were no explicit orders to exterminate. In the first phase a village was usually subjected to heavy artillery from distance. Then soldiers would assault the village. After giving up resistance, the Arab fighters would withdraw while attempting to snipe at the advancing forces. Some would not flee and would remain in the village, mainly women and old people. In the course of cleansing we used to hit them. One was “tailing the fugitives,” as it used to be called (“mezanvim baborchim”). There was no established battle procedure as today, namely that when blowing up a house, one has first to check whether civilians are still inside. In a typical battle report about the conquest of a village we find: “We cleansed a village, shot in any direction where resistance was noticed. After the resistance ended, we also had to shoot people so that they would leave or who looked dangerous.”

The historian Uri Milstein, a myth-shatterer, corroborates Yitzhaki’s assessment regarding the massacres’ extent and goes even further. “If Yitzhaki claims that almost in every village there were murders, then I maintain that even before the establishment of the State, each battle ended with a massacre. In all Israel’s wars massacres were committed but I have no doubt that the War of Independence was the dirtiest of them all. All over the world, massacres constitute an integral part of the norm of war and it is in fact the fundamental basis of human conduct in a situation of battle. The idea behind a massacre is to inflict a shock on the enemy, to paralyze the enemy. In the War of Independence everybody massacred everybody, but most of the action happened between Jews and Palestinians.”

“If Yitzhaki claims that almost in every village there were murders, then I maintain that even before the establishment of the State, each battle ended with a massacre.”

Milstein adds: “In my opinion, the regular armies of Arab states were less barbaric than the Jews and the Palestinians. Until the entry into the battle of the Arab armies, the concept of taking prisoners was unknown. The regular armies, especially that of Jordan and Egypt, were the first in the region who did not kill prisoners, as a matter of principle. Not that they were exceptional, but they killed the least of all, relatively speaking. The Jordanian Legion even succeeded to stop Palestinians of massacring Jews in Gush Etzion, at least in a part of this area. The education in the Yishuv at that time had it that the Arabs would do anything to kill us and therefore we had to massacre them. A substantial part of the Jewish public was convinced that the most cherished wish of say, a nine-year old Arab child, was to exterminate us. This belief bordered on paranoia.”

A careful study reveals that until today over twenty massacres were publicly reported. The testimonies were not published in one collection, a fact which adds to this phenomenon another dimension. At least eight massacres were described by Benny Morris in his book “The Birth of the Palestine Refugee Problem.” Two cases were reported in Milstein’s books. Two cases are reported in the book of Palestinian historian Arif al-Arif. The rest were reported in novels, memories and the press. But it appears that at least eight more massacres were committed which are reported here for the first time. Two of them were discovered by Yitzhaki, three by Milstein, one case was revealed by Kurtzman and was presented in the introduction to this reportage. One case was brought to our knowledge by a kibbutz member who wishes to remain anonymous and one more case was revealed by Dov Yirmiya.

The testimonies concerning the massacres, revealed here for the first time by Yitzhaki, are kept in the IDF archives. Those who wish to study the documents in question confront a blank refusal. The director, Miki Kaufman: “If you are looking for what I believe you are looking for, then you can forget it. In any case, just keep in mind that we are reading over any documents before you are allowed to see them and we cull out material that you should not see.”

A person who already had to face this barrage is Benny Morris. He addressed himself to the State Archivist to get a report by the government-nominated Shapira Committee, on killings in the War of Independence, but his request was denied.

“The Archivist refused to let me see the report and I went then to the Supreme Court. According to the [State] Archives Law (1953), access is open to documents concerning [government] policies and political matters after 30 years and documents related to security matters after 50 years. As the report by the Shapira committee is a political document issued by the Ministry of Justice, it was to be accessible by the public. But after I entered my request to the State Archivist and to the courts, the State Prosecutor and the Archivist made me a trick. It appeared that by convening a special meeting of at least two Cabinet members – in this case Arens and Sharir – it was possible to extend indefinitely the classified status of any archived document by arguing that disclosure might endanger state security. The meeting was duly convened and the document was reclassified . . .”

But Yitzhaki kept the testimonies. The first case he presents happened in Tel Gezer. A soldier of the the Kiryati Brigade . . . testifies that his colleagues got hold of ten Arab men and two Arab women, a young one and an old one. All the men were murdered. The young woman was raped and her destiny was unknown. The old woman was murdered. Yitzhaki tells that he discovered the testimony in a specific folder containing testimonies from Guard Units (Kheil Mishmar) in the IDF archives. Later he also obtained an oral testimony about this event from a person who wished to remain anonymous.

Another case happened in Ashdod. Towards the end of August 1948, the Giv’ati Brigade executed the “Cleansing Campaign” (Mivtza Nikayon) in Ashdod’s dunes. This happened after the forced landing of an Israeli plane in the area and the killing of his eight passengers by locals. A company of mounted cavalry, jeeps and Giv’ati fighters went to comb the area. In the course of this action, and according to a conservative estimate, ten farmers (“fellahin”) were murdered. Yitzahki says that evidence about that can be found in the campaign chronicle of Giv’ati in the IDF archives and in the second chapter of the book on the Giv’ati Brigade.

“Apart from these cases,” says Yitzhaki, “there are more cases described in IDF’s archives, but I don’t want to disclose them at this stage. I will yet write a book.”

The historian Uri Milstein presented in his book series “The History of the War of Independence” a number of massacres. Three more cases came to his knowledge after he finished writing. One case happened in Ayn Zaytoon. According to Milstein two massacres happened there in addition to the case described by Netiva Ben Yehuda in her book “Within the Bounds” (mibe’ad la’avutot). Milstein possesses a testimony from a soldier named Aharon Yo’eli: “Three men from Safad came to Ayn Zaytoon, they took 23 Arabs, told them they were murderers and gangsters, took from them their watches and put them in their pockets, led them over the hills and killed them. This was the revenge of the Jews of Safad. I understood that our commanders were looking for additional killers to execute such jobs. Not everybody in Safad was a hassid [strictly observing Jew]. In my opinion this was not the execution of prisoners but the killing of Arab murderers. The rest were expelled in the direction of the Germak that same evening and to make them go fast, we shot at them.”

The second case was reported to Milstein by a soldier named Yitzhak Golan, as he referred to thirty prisoners who were brought to interrogation in Har Kna’an: “The men of the Intelligence Unit interrogated them and after the interrogation the question came up what to do with them. We were told to take them down to the Rosh Pina police station. On the way they attempted to escape so we shot at them. There was no alternative. The danger was that they might reach Safad and would tell there how few weapons and manpower we had. It is possible that they were killed chained. Next morning a platoon was sent to bury them.”

Another case happened in Caesarea. In February 1948 the Fourth Battalion of the Palmach forces, under the command of Josef Tabenkin, conquered Caesarea. According to Milstein, all those who did not escape from the village were killed. Milstein gleaned testimonies about this fact from fighters who participated in the conquest.

A member of Kibbutz Be’eri, who was assigned to the Guard Milices for a short time, reveals another unpublished case about the murder of an Arab soldier: “We were in the strong point in the Wadi Ara area, near Giv’at Ada. Not far away was a post of Palestinians who fired from time to time at us. One night we raided their post and brought back a prisoner for interrogation. One of the soldiers of the Guard Milices took the prisoner after interrogation, beheaded him and with a knife scalped the head. No one present tried to stop him. He then tied the skin to a high pole facing the Palestinian post to inspire a deadly fear among the Palestinians. This soldier was later brought to the battalion commander for trial.”

On 20 May 1948 the Karmeli Brigade conquered the village Kabri. Dov Yirmiya, who was a company commander in the 21st battalion, tells: “Kabri was conquered without a fight. Almost all inhabitants fled. One of the soldiers, Yehuda Reshef, who was together with his brother among the few escapees from the Yehi’am convoy, got hold of a few youngsters who did not escape, probably seven, ordered them to fill up some ditches dug as an obstacle and then lined them up and fired at them with a machine gun. A few died but some of the wounded succeeded to escape. The battalion commander did not react. Reshef was a brave fighter and as a rescapee from the Yehi’am convoy, enjoyed special status in the battalion. He advanced later to the grade of Brigadier General. He justified his action as an act of revenge.”

“When the action ended, we left, namely the battalion commander Dov Tschitchiss, Education Officer Tzadok Eshel, the driver and myself. We drove over fields to Nahariya. While driving we saw refugees escaping to the North. The battalion commander ordered the driver to stop and went with the driver and the Education Officer to chase an Arab who was escaping with a girl eight or nine years old. I heard shots and had scarcely the time to understand what happened. When they returned, the battalion commander declared: We killed them. I asked: The girl too? And he answered to me: No, no, we did not kill the girl.”

The Education Officer, Tzadok Eshel, has already forgotten about the episode. “In our Carmeli Brigade,” he said, “we did not commit massacres. I can tell you about the massacre that the IZL people did in Haifa. It was typical for the IZL and the LEHI, not to us. It was totally outside our way of thinking. There was the case of an officer who wanted to loot a village but they did not allow him.”

After hearing the testimony of Yermiya, Eshel changed his version: “Did I tell you about this case, no? . . . Probably I forgot . . . Yes, there was in fact one case where we drove in a jeep and an officer, I don’t remember who, but I don’t think it was the battalion commander, wanted to shoot down an Arab with a girl. I told him that if he will fire at them, I will shoot at him. When we returned to the jeep I felt good that I succeeded to stop such a thing.” Yirmiya, in his testimony mentions [however] shots, “I don’t at all remember that I was in the jeep. I was in the area. I tell you, you better leave these things. There were no such things.”