Community Security Trust Throws Its Weight Around

Britain’s Jewish Community

I have written a number of times about the Community Security Trust, a group allegedly devoted to protecting British Jews from anti-Semitism, that was set up by the Board of Deputies of British Jews. About how it manipulates and distorts statistics of anti-Semitic incidents for its own, Zionist, purposes. When 2 posts were sent to this blog, one from a fascist, claiming the Holocaust was a myth and the other, from a Zionist, wishing that I and my family had perished in the gas chambers, the CST only recorded the first post as anti-Semitic! When is an anti-semitic attack not anti-semitic? When it’s a Zionist who is being anti-Jewish

The CST’s primary function is to protect the Jewish community from anti-Zionists, especially Jewish anti-Zionists. It is used primarily to steward Zionist meetings and events and its goons have on more than one occasion attacked and assaulted anti-Zionists who have dared open their mouths. See for example CST Thugs Violently Eject 2 Jewish People from Zionist ‘Environmental’ Meeting, Community Security Thugs Bar Jewish Opponents of Gaza War from Liberal Judaism Meeting and The Community Security Trust – Policeman of the Jewish Community.

The CST targets the Left and works closely with the Metropolitan Police, which says all you need to know about its anti-racist credentials. The corrupt and institutionally racist Metropolitan Police actively promote the CST within the Jewish community over and above other organisations (see articles by Geoffrey Alderman below). This is nothing new for the Police, whose ‘community’ strategy has always meant promoting favoured groups within what it sees as minority ethnic communities, at the expense of those groups it can’t control.

It was therefore no surprise that the CST, along with other Zionist groups, via its spokesman Mark Gardener, attacked the University & College Union (UCU) for rejecting the European Union Monitoring Committee’s Working Definition on anti-Semitism. In fact this definition, drawn up originally by the European Jewish Congress and the American Jewish Committe, has been abandoned by the EUMC’s successor, the Fundamental Rights Agency and was itself the subject of arm twisting and naked blackmail.

The Working Definition is not only a useless definition in terms of collating statistics of anti-Semitic incidents, because it is subjective and therefore depends on individual interpretation, but because it conflates criticism of Israel and Zionism with attacks on Jews and anti-Semitism.

The CST is particularly dishonest about this because, as Tony Lerman shows below, the CST itself doesn’t itself adopt the MacPherson definition of racism when it comes to classifying anti-Semitic incidents, for the simple reason that MacPherson’s definition came out of Police racism and was applicable solely to that organisation. If anti-Semitism was simply in the eye of the beholder then any fool or charlatan could claim to be the victim and any statistics collected would be meaningless.

It is essential therefore, if statistics of anti-Semitic incidents are to have any value, that there be an objective basis to such a classification. When I sent the posts in question to the CST I made it clear that I considered both of them to be anti-Semitic. The CST disagreed. In their view Jews can never be anti-Semitic, even when they wish the Holocaust had been visited on other Jews. This is of course a political definition of anti-Semitism and one favourable to the Zionist movement, since Zionists are often the most anti-Semitic of all individuals.

The CST itself instead of using the EUMC uses the definition in the Race Relations Act 1976 and Equality Law 2010, to define racial harassment both on the basis of individual perception (i.e. a subjective defintion) and on what is reasonable to treat as a racist incident i.e. an objective definition.

What is even more hypocritical is that in the long years between the murder of Stephen Lawence and the MacPherson Inquiry, the Board of Deputies and CST weren’t in the slightest bit interested in the Stephen Lawrence campaign. How much money or support did the CST or the Board of Deputies give to the Campaign? What publicity did they provide etc? None is the answer. You will find no mention of the Stephen Lawrence campaign in the Jewish Chronicle or the outpourings of the Board and CST.

How many Zionists who now try to misuse the MacPherson definition of a racist incident, actually went to listen to the inquiry at Elephant & Castle to see young Black people full of hope that the Met would get its come-uppance? Again none. Like the parasites they are, the CST feeds upon a definition of racism against Black people, it wasn’t in the slightest bit interested in. Anti-semitism is in any case not an example of state racism and is therefore even less suited to the MacPherson definition.

The Chair of the CST’s Trustees is Gerald Ronson, who was imprisoned in the Guiness Trial Affair some years ago. He is a right-wing private capitalist, who owns the Heron Group, which was (and maybe still is) the largest private company in Britain. He is part of a mafia of right-wing Jewish businessmen in Britain who promote a far-right and overtly expansionist Zionism within the Jewish community (others such include Stanley Kalms of Dixons and Richard Desmond of the EDL supporting Daily Express/Star).

The CST, as Zionist dissident (but venomous right-winger Geoffrey Alderman (see Jewish Chronicle Columnist Geoffrey Alderman expresses his ‘pleasure’ at the murder of Vittorio Arrigoni, Italian and ISM Peace Activist) shows the CST as a pretty secretive and sinister organisation. It goes to great lengths to hide the names of those in charge of it, having managed to persuade the Charity Commission that uniquely its trustees should not be named on the CC website.

Researching charities and trusts for my own organisation, I was struck by a remarkable thing – how a large percentage if not an actual majority – of Jewish charities in this country give money to the CST. Why, I asked myself? And the answer seemed obvious. The CST has a vested interested in whipping up fears of ‘anti-Semitism’ where it doesn’t exist (Palestine solidarity) and ignoring it where it does exist (English Defence League and other fascist mobilisations see Zionist Federation & fascist EDL Join Hands in Supporting Israel’s Murder at Sea

The result is an organisation overflowing with cash, with some £3m at least in reserves, paying large salaries to a host of its senior officers. Never has ‘anti-racism’ been better paid with people like Mark Gardener and Dave Rich receiving salaries of over £150,000 pa, which are far higher than the equivalent salaries in the voluntary/third sector. So under the guise of fighting racism, we have an organisation which combines racism and high salaries for the few. When it appeals for money you can bet on the fact that it doesn’t advertise the fact that over £2m of its budget will be spent on salaries alone.

I am copying below therefore two articles by Alderman in the Jewish Chronicle and two articles by Tony Lerman, co-founder and former Director of the Institute of Jewish Policy Research, whose independence of mind led people like Stanley Kalms to call for his sacking.

·

By Geoffrey Alderman, June 10, 2011

A month ago today, the second most senior police officer in the Metropolitan Police, Deputy Commissioner Tim Godwin, chaired a meeting at New Scotland Yard. A source close to the Community Security Trust told me that the meeting had been held, and that, apart from Deputy Commissioner Godwin the only persons present were representatives of the CST and the Jewish Police Association.

According to the Met’s press office, the reason for the meeting was to deliberate on how these three bodies might work together “to achieve a secure and confident London Jewish community.” How curious, therefore, that while the CST had been invited, the Board of Deputies had not.

In my JC column of April 15, while acknowledging that the CST probably did valuable work providing security and security advice, and collecting and publishing security-related data, I asked whether it could justly claim to “represent” the Jewish community.

I asked this question in the context of its sizeable budget, the large salaries paid to certain of its employees, and the fact that the names of its trustees were hidden from public view.

Protected by the Home Office and the Met, it had, he said, got too big for its boots

This seemed to me a perfectly reasonable question to ask. When the JC published in response a letter of condemnation signed by no less than 27 communal grandees, including six vice-presidents of the Jewish Leadership Council, I knew that I had been right to ask the question, and that it had been the right question to ask.

But what I did not know when I researched and composed that article was that other members of British Jewry – rather less self-important individuals than the aforementioned 27 protesters – felt exactly as I did.

Take, for example, the Manchester-based rabbi who contacted me to say how deeply he resented the intrusion of the CST into the affairs of his community – he meant the CST’s insistence that he consult them when planning any communal event.

Take the south-of-England rabbi who phoned me to complain of the telling-off he had received from the CST because, without their consent, he and his lay leadership had agreed to permit a local non-Jewish group to meet on synagogue premises.

Or take the Charedi community activist who asked to meet me (which he did) in order to unburden himself of the deep cynicism with which he regarded the CST.

It had, in his view, got too big for its boots while basking in the privilege and protection it received from the Home Office and the Metropolitan Police.

Then there is Nochum Perlberger, the head of the Stamford Hill Shomrim – who provide civilian security patrols and whose efforts to counter crime and anti-social behaviour have had exceptional results. Mr Perlberger confessed to me that one of the conditions of their recognition by the police in Stoke Newington was that they liaise with the CST.

And last, but by no means least, take the Jewish Police Association.

Ethnically-based police associations are not everyone’s cup of tea. But Jewish members of the police service (which included my own maternal grandfather, incidentally) have special needs and, as professional crime-fighters, can make a unique contribution to cementing the relationship between the police and the UK’s Jewish citizens, many of whom come from backgrounds laden with suspicion of anyone wearing anything resembling a uniform.

So it was natural that Mr Perlberger and his friends should have turned to the JPA for advice when the Shomrim were being formed. It was equally natural that the JPA should want to liaise with Jewish schools, and introduce themselves to Jewish communities.

Natural, yes. But with the blessing of the CST? Hardly. As Rabbi Geoffrey Shisler, one of the JPA’s chaplains, put it to me, “there have been some tensions between the JPA and the CST in the past. However, a meeting was held recently between the Met and both those organisations, and it is hoped that they have now been smoothed out.”

Which brings us back to the meeting chaired by Deputy Commissioner Godwin on May 10.

My understanding is that this gathering was instigated by the CST, and that its purpose was to make it clear to the JPA that they must take no initiative without the CST’s knowledge and approval.

Is this what the 27 aforementioned communal bigwigs really meant when they referred to the Community Security Trust’s “meaningful representation”?

·

By Geoffrey Alderman, April 18, 2011

In the JC of March 11, there was an article by Dr Gilbert Kahn, who teaches political science at Kean University, in the United States. Professor Kahn had attended the annual fund-raising dinner of the Community Security Trust, and the purpose of his column was to lament the fact that British Jews felt obliged to pay – via the CST – for the physical protection that the British state should surely provide out of general taxation.

I want to ask some rather different questions.

What right does a completely private body that happens to call itself the CST have to involve itself in the safety and well-being of British Jews?

What right does it have to represent itself as being a representative body? On its website, the CST boasts that it “represents the Jewish community on a wide range of Police, governmental and policy-making bodies dealing with security and antisemitism.”

What right does it have to make such a claim? The website further explains that “the Police and government praise CST as a model of how a minority community should protect itself.”

That may be so but I want to ask whether we – you and I – should not have a quiet word in the ear of government and point out that the CST represents no one but itself and is mandated to espouse the views of none other than its own trustees.

Since what I am going to say is likely to raise more than a heckle here and a heckle there, I want to make it clear that I personally believe that the CST probably does valuable work in two related fields: providing security and security advice; and collecting and publishing security-related data.

I am aware that it operates in a third and inevitably murky dimension, namely that of a watching brief with regard to extremist organisations, possibly including the infiltration of such bodies.

Last year, in a volume of essays I edited by young historians of British Jewry (New Directions in Anglo-Jewish History) I was delighted to include a chapter written by Daniel Tilles on the anti-fascist campaign of the Board of Deputies, between 1936 and 1940.

Mr Tilles had been permitted access to hitherto closed files that revealed how the Board had operated a crude network of informers at that time.

The Board’s defence director, Mike Whine, was candid enough to confess to me that the Board had decided to open these historic files partly to send a very contemporary message: that British Jewry was not averse to such intelligence-gathering, and that groups currently touting an anti-Jewish agenda would do well to understand this fact.

Mr Whine, as well as being the current defence director of the Deputies is also an employee of the CST, in charge of government and international affairs. The CST also elects two deputies of its own. I see nothing problematic in these arrangements, but we must fully understand the corollary, namely that the CST itself has no “representative” basis whatsoever.

The CST grew out of the Community Security Organisation, which became independent of the Deputies in the 1980s.

It enjoys charitable status, so you can discover a certain amount of information about its structure and financing via the website of the Charity Commission.

In 2009 (the latest year for which accounts are available), it attracted more than £5 million in donations and boasted reserves of £3 million. It had 64 employees, one of whom received an annual emolument of between £150,000 and £160,000. Its total 2009 wage bill exceeded £2 million.

These are not small amounts; they contrast starkly with the services provided to the CST practically for nothing by the scores of volunteers who, under the badge of the CST, provide security for communal events up and down the land.

Who makes policy at the CST? The short answer is: its trustees, who appoint themselves. Under a dispensation granted by the Charity Commission, the names of the trustees are hidden from public view.

According to the Commission’s website there is only one trustee – Support Trustee Limited. But if you go to the Companies House website you can, for a small fee, download the names and contact addresses (and indeed dates of birth) of the directors of STL.

Perhaps these individuals could explain to us how, given the constitution and structure of the CST, it can honestly claim to “represent” the Anglo-Jewish community in any meaningful sense.

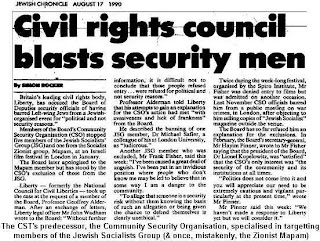

There’s been much wailing and gnashing of teeth from those sickened by the Universities and Colleges Union’s decision to ban use of the European Union Monitoring Centre’s ‘working definition’ of antisemitism. At the UCU’s annual congress in Harrogate a large majority supported Motion 70 that resolved:

1. that UCU will make no use of the EUMC definition (e.g. in educating members or dealing with internal complaints)

2. that UCU will dissociate itself from the EUMC definition in any public discussion on the matter in which UCU is involved

3. that UCU will campaign for open debate on campus concerning Israel’s past history and current policy, while continuing to combat all forms of racial or religious discrimination.

The stated reason for this decision?:

Congress believes that the EUMC definition confuses criticism of Israeli government policy and actions with genuine antisemitism, and is being used to silence debate about Israel and Palestine on campus.

Critics of the UCU’s decision are having none of this. Jeremy Newmark, chief executive of the Jewish Leadership Council said: ‘After today’s events I believe the UCU is institutionally racist’. His view was echoed by Jon Benjamin, the chief executive of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, who said ‘the UCU has . . . simply redefined “anti-Semitism” itself. . . The truth is apparent: whatever the motivations of its members, we believe UCU is an institutionally racist organization’. Martin Bright, the political editor of the Jewish Chronicle, tweeted: ‘opens gates to campus antisemitism’. Paul Usiskin, chair of Peace Now UK, said: ‘The UCU legitimises and perpetuates the evil of antisemitism.’ The Fair Play Campaign Group issued a statement that ended: ‘The truth is apparent: whatever the motivations of its members, we believe UCU is an institutionally racist organisation’. Ronnie Fraser, director of the Academic Friends of Israel, delivered an emotional speech opposing the motion. He said the union had crossed a red line, and ‘only antisemites would disassociate themselves from the EU Working Definition and vote in favor of the resolution’. John Mann MP, chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group Against Antisemitism, is taking the charge of ‘institutional antisemitism’ against the UCU so seriously that he has stated that the claim ‘should be investigated independently, ideally by the EHRC [Equality and Human Rights Commission]‘.

Despite these furious reactions, the motion does not say the UCU must now ignore instances of antisemitism. On the contrary, it acknowledges that there is a ‘genuine antisemitism’ that must be fought, and that the UCU must continue ‘to combat all forms of racial and religious discrimination’. But the critics make it clear that they don’t trust the UCU; that by making it impossible to call to account, on the basis of the EUMC’s ‘working definition’ of Israel-linked antisemitism, critics of Israel who are seen as crossing a line into antisemitic discourse, licence is effectively being given to antisemites in the UCU to express antisemitic sentiments.

It’s hard to believe that the EUMC ‘working definition’ is the only bulwark preventing the UCU from giving free rein to its alleged institutional antisemitism or, deliberately or otherwise, from encouraging and then turning a blind-eye to campus antisemitism. Yet this is undoubtedly what the union’s critics seem to be arguing, often in a language that borders on the apocalyptic. But to be fair on the critics, the language of some of those who have campaigned to distance the UCU from the EUMC ‘working definition’ is also pretty extreme and unbalanced.

And surely, therein lies the problem. Reading the live blogging from the congress, the speeches, recriminations, reactions and past reports on this long-running battle, which essentially began when the union initially voted on an academic boycott of Israeli universities back in 2005, the sense that much of this is taking place in a hothouse that has tenuous links to reality is rather powerful.

First, in the wider world of discussion about antisemitism, the notion that civilisation as we know it is about to come to an end because the UCU has distanced itself from the EUMC definition is quite absurd. It’s true that the status of the ‘working definition’ has changed significantly. The EUMC no longer exists and has been replaced by the EU’s Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), which seems to have more or less abandoned the ‘working definition’. The FRA appears not to believe that the definition is a useful working tool. An FRA official told Richard Kuper: ‘Since its development we are not aware of any public authority in the EU that applies it’. Moreover, ‘The FRA has no plans for any further development’ of the ‘Working Definition’, the official said. And in its latest publication on the topic (August 2010) it doesn’t even mention the ‘working definition’.

Nevertheless, if the FRA were intending to go further and reverse the current status of the definition among national and international agencies, whether governmental or non-governmental, as well as among antisemitism research institutes and monitoring bodies, it would almost certainly encounter an impossible task. For despite the fact that it was called the ‘working definition’ and that the contentious clauses exemplifying different ‘ways in which antisemitism manifests itself with regard to the state of Israel taking into account the overall context’ were not described as a priori antisemitic, the EUMC document has virtually become the definition for such organizations, with practically the status of a holy text. The US State Department treats it as gospel in its antisemitism reports. The influential All-Party Parliamentary Enquiry into Antisemitism urged the British government to adopt it formally. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) employs the definition. The European Forum on Antisemitism, founded in 2008 with participants from 15 European countries as well as the USA and Israel, but effectively a front organization for the American Jewish Committee, seems to exist primarily to promote use of the working definition. The Anti-Defamation League and the Simon Wiesenthal Centre back it, as does the European Jewish Congress and numerous official national Jewish representative bodies and Jewish communal defence groups. (Mark Gardner, communications director of the Community Security Trust, which describes itself as ‘protecting the Jewish community’ in the UK, mounted a vigorous defence of the working definition just days before the UCU vote.) Set against this phalanx of international support for the ‘working definition’, the UCU vote is but a mere pinprick.

And it’s a sad fact that the existence and extensive promotion of the ‘working definition’ has done as much as anything to legitimise the discourse of the ‘new antisemitism’, the notion that Israel has become the Jew among the nations and that therefore extreme criticism and anti-Zionism are a new version of the antisemitism that existed prior to the establishment of the state. Rather than make it easier to identify antisemitism, the promotion of the ‘working definition’ and the entrenchment of the concept of the ‘new antisemitism’ have so extended the range of expressions of what can be regarded as antisemitic that the word antisemitism has come close to losing all meaning. And it therefore makes agreement on what is and what is not antisemitic more fraught and more contentious. It’s a simple fact that until the early 1990s, before the idea of the ‘new antisemitism’ gained acceptance and before the ‘working definition’ was introduced, there was broad agreement on the nature of contemporary antisemitism. Today, scholars and commentators writing on current antisemitism are bitterly divided among themselves.

Second, the responses (quoted above) from Jewish community officials and representatives and other defenders of the ‘working definition’ show a complete lack of balance. If Ronnie Fraser is correct and only ‘antisemities’ would dissociate themselves from the ‘working definition’, this places a significant number of highly respected Jewish and non-Jewish academics working in the field of antisemitism research in the dock. And it would mean that the FRA officials, who have clearly sidelined the original EUMC document, are also antisemites. John Mann MP should thus be clamouring for these Jew-haters to be brought before the European Court of Human Rights, just as he wants the UCU to be investigated by the EHRC in the UK.

Typifying the tenor of these responses is the myth, succinctly articulated by the Board of Deputies chief executive Jon Benjamin, that it’s the UCU that is redefining antisemitism. In fact, it’s the EUMC that redefined antisemitism. What the UCU seems to have done is seek to revert back to the time when a common sense consensus about the nature of antisemitism existed. Even Mark Gardner, in his CST blog piece, acknowledges that there has been such agreement:

The “working definition” is not so necessary in Britain perhaps, where antisemitism is generally well understood and defined by politicians, courts, Police and Jews

(although he rather cheekily omits mention of academics, since it would undermine the tone of much of his piece, which casts certain academics as villains). As Richard Kuper writes in an updated analysis of the ‘working definition’ just published on openDemocracy, Benjamin, Fraser and others

[make] you wonder what happened before “the definition” was propagated in 2005 (when presumably no-one had a clue as to what antisemitism was, and without this particular document no-one now would have either).

Given that hardly any discussion of contemporary antisemitism takes place today without Israel, Zionism or anti-Zionism cropping up, it was probably unrealistic of the UCU anti-EUMC definition protagonists to think that we can all just return to the status quo ante. But it’s not a redefinition that’s required, rather a clarification of how certain forms of discourse on Israel can fall into the classic definition of antisemitism around which academics and researchers can reach agreement – and indeed we have such a clarification in the form of Dr Brian Klug’s article ‘The collective Jew: Israel and the new antisemitism’ (which he recently updated for his book Being Jewish and Doing Justice). And what’s interesting about Klug’s article is that it figures prominently in the EUMC’s report, Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002-2003, published in 2004, the report credited for being the impetus for the framing of the ‘working definition’. According to Mark Gardner and others:

The Monitoring Centre compiled the ‘working definition’ because this was a central recommendation of its own 345 page report ‘Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002-2003.’

A convenient story, but untrue. If the ‘working definition’ had really emerged from this report, it’s hardly likely to have diverged so radically from Klug’s formulation of a consensus definition of antisemitism that the report quotes from so favourably, but diverge it most certainly does.

The truth is that it was the first report on manifestations of antisemitism in the EU compiled by researchers at the Zentrum für Antisemitismusforschung (Centre for Research on Antisemitism) at the Berlin Technical University, completed in 2002 but never published by the EUMC, which led to the framing of the ‘working definition’. It was the Board of the EUMC that took the decision not to publish and a huge controversy erupted when the whole affair became public.

The official reason given by the Centre was that the methodology was flawed and its findings deemed to be biased. But it’s widely believed that the real reasons for the suppression of the report were somewhat different. Some members of the Board were unhappy that hostility to Israel was included and that the report laid the blame for much of the post-2000 upsurge in antisemitic incidents in Europe on young Muslims and pro-Palestinian perpetrators. Jewish members of the Board linked to the European Jewish Congress based in Paris were angry and leaked the report to the press, complaining that appeasement of Europe’s large Muslim population was behind the decision not to publish. The resulting bad publicity severely embarrassed the EUMC and its director, Beate Winkler, damaged its reputation and left Winkler in a state of depression.

Enter the American Jewish Committee in the form of its Director of International Affairs, Rabbi Andy Baker, who had been active in Europe for many years, making and maintaining connections with Jewish communities, Jewish leaders, national politicians, EU politicians and the Council of Europe, and taking a special interest in antisemitism. Baker knew Winkler and met with her in the aftermath of the controversy. He saw that she was weighed down by the criticism levelled at her and the EUMC and that she had no plan as to how to restore the organization’s reputation.

Baker’s diagnosis was that the problem arose because the EUMC had no definition of antisemitism that would satisfy Jewish leaders, activists and researchers and he proposed to Winkler that she move quickly to convene a meeting of such people from Jewish circles to draft such a definition. Baker was clear in his own mind that the essential element in such a definition would be singling out certain forms of criticism of Israel and Zionism as antisemitic. I doubt whether he told this to Winkler, who was persuaded of the value of the course of action Baker had proposed. But he knew that those invited to the meeting would need to be broadly sympathetic to the concept of the ‘new antisemitism’ and since Winkler was not well-versed in the names of people working in the area of antisemitism research, he was able to determine who attended.

I believe the initial meeting took place in summer 2003. In fact I got wind of it – and this was long before I learned the details I’ve just recounted, details told to me directly and triumphantly by Andy Baker in, if memory serves, 2005 – at the time from Pascale Charhon, who was then running CEJI (Centre Européen Juif d’Information), a Brussels-based body linked to the Anti-Defamation League. I believe that Charhon had been consulted by Baker on who to invite though was not privy to Baker’s particular agenda. She sounded me out as to whether I could attend an EUMC discussion on antisemitism, which was due to take place within a week or two. I said I would try to come (I was on vacation abroad at the time). But Andy Baker knew about my opposition to the concept of the ‘new antisemitism’ so, not suprisingly, I never received an invitation.

At this point, my story meshes with Richard Kuper’s account in his openDemocracy article, when he describes the meetings that then took place, from which those who were not sympathetic to the ‘new antisemitism’ thesis were excluded and at which the AJC itself, in the form of Kenneth Stern, the organization’s principal expert on antisemitism, took the leading role. I understand that a draft of the ‘working definition’ was circulated more widely before it was finally released and it may have been as a result of feedback then received that the formulations of Stern and his colleagues, which contained no qualifiers – so that, for example, ‘Holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the state of Israel’ would always be antisemitic – were altered to read ‘could’ be antisemitic, ‘taking into account the overall context’.

Andy Baker’s ‘personal’ initiative – but one that was fully in tune with the AJC’s increasingly hard-line, pro-Israel agenda, its aim to be a major player in Europe, influencing European action on antisemitism and appearing to command a leading ‘advisory’ role on the European Jewish stage in order to appeal to its domestic American Jewish constituency from whom the organization raises the many millions of dollars required to keep it afloat – has proved remarkably effective. I doubt very much whether he expected what he proposed to Beate Winkler as a fix for the EUMC and a feather in the cap of his organization to achieve the iconic status it now occupies.

But the truth is that, given the genesis of the ‘working definition’, which in my view was a scandal, the fulminations of the Jewish establishment, the CST, Engage, John Mann MP, the World Union of Jewish Students etc. over the UCU vote are farcical. Certainly, the UCU activists who pressed for the adoption of Motion 70 are not angelic philosophical types approaching this issue with nothing but defence of the purity of academic research in mind. They have a political agenda in relation to Israel-Palestine and they’re fighting for it and their tactics are not pretty. It’s not an agenda I share, but as Professor David Newman of Ben Gurion University, who spent a few years in the UK combating proposals to institute a boycott of Israeli academic, concluded, it’s a political fight that needs to be fought with political arguments, not with accusations of antisemitism.

The critics of the UCU decision don’t seem to understand this. They think nothing of accusing Jews who see things differently from them of being antisemitic. At one moment they tell us the ‘working definition’ is ‘the EU definition’ (which it isn’t and it never was). The next moment they tell us it’s only advisory and is a work in progress. They manipulate the findings of the report of the Macpherson inquiry into the killing of the black teenager Stephen Lawrence and falsely claim it decreed that only members of the group who experience racism can define what that racism consists of – so that anyone who denies Jews exclusive rights to define what is and what is not antisemitism – i.e. the UCU – is antisemitic.

If only the UCU vote did indeed signal the demise of the EUMC ‘working definition’. It would open up far more possibilities for rational discussion about the nature and danger of antisemitism today, discussion that would not be rendered moot by those who are determined to politicise the subject. But I’m not holding my breath.

How Feelings of Jewish Insecurity are Aggravated by the Community Security Trust

13/06/2011 Antony Lerman

I have always given credit to the Community Security Trust, the private charity that monitors and combats antisemitism in the UK, for its efforts to record expressions of antisemitism as diligently and rigorously as possible. Some accuse CST of deliberately exaggerating the numbers of antisemitic incidents – as if they were actually manufacturing reports from individuals and adding them to their lists – but I don’t believe for one second that this is the case. They go to considerable lengths to ensure that their statistics on manifestations of Jew-hatred are credible. And one very important testament to this is their polite but firm distancing of CST from the Macpherson Report’s recommendation that any racist incident must be recorded by police according to the categorization of it by the victim (I referred to this in a previous post Don’t Distort Macpherson Report’s Recommendations on Racism to Attack the UCU

The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry definition of a racist incident has significantly influenced societal interpretations of what does and does not constitute racism, with the victim’s perception assuming paramount importance. CST, however, ultimately defines incidents against Jews as being antisemitic only where it can be objectively shown to be the case, and this may not always match the victim’s perception as called for by the Lawrence Inquiry. CST takes a similar approach to the highly complex issue of antisemitic discourse.

But where I and others have differences with CST is over the interpretation of the data they collect and the manner in which they carry out their self-appointed mandate to act as the guardian of the security of the UK Jewish community. And I have always been especially concerned to establish that it is perfectly right for the CST to be subject to public scrutiny of its operations; that a reasoned critique of what it does coming from within the Jewish community is entirely legitimate and should not be seen as unacceptable.

So I was greatly heartened to read Geoffrey Alderman’s recent two columns in the Jewish Chronicle, on 18 April and 10 June, taking the CST to task by questioning whether it ‘represents’ the Jewish community and arguing for much greater transparency about its policy-making and operations. I can hardly say that Alderman and I see eye-to-eye on many things, but on this issue – one which I first began to raise 10 years ago – I think he has done us all an important service by airing his concerns in public.

Unsurprisingly, the CST did not like Alderman’s intervention and he was slapped down in a letter to the JC from 27 communal grandees. Reporting this in his second piece on 10 June, Alderman provided evidence from decidedly un-grandee-like members of the community supporting his concerns. These criticisms of the way the CST operates echo numerous comments community activists and professionals have made to me privately, insisting that they did not want their names to be made public if I ever wrote about the issue. Most had dual reasons for wanting to remain anonymous: first, because they feared that the CST could try to pressure their employers, or the organizations they worked for on a voluntary basis, to oust them; second, because they were aware that such a climate of fear of antisemitism exists that they did not want to be seen to be undermining efforts to combat antisemitism, even though they did not believe that the climate was justified.

Interestingly, Alderman is not alone in publicly expressing reservations about ‘communal policy’ on antisemitism. In a remarkable op-ed on 2 June in the JC, ‘Don’t let antisemitism take over our narrative’, Rabbi Jonathan Wittenberg conveyed his fundamental concerns:

‘Either you’re for us or you’re totally against us’ expresses an oversimplified, often bigoted world-view. It’s easy to brand others as antisemites, hard to engage at the borders between ourselves and those who don’t see the world as we do. . . . My point is that we shouldn’t make ‘the world hates us’ our motto.

Whether or not he was referring directly to CST as being largely responsible for encouraging this mindset, I don’t know. But you only have to read the response of the Chairman of the CST, Gerald Ronson, to Alderman’s questions and criticisms, which Ronson gave in a JC op-ed on 29 April, to realise that the size, reach and influence of CST makes it perfectly capable of being a prime mover behind the creation of a ‘the world hates us’ atmosphere in the community.

And now we have a further deeply thoughtful and searching critique of the whole notion of ‘security’ and the role of the CST in a superb article by Rabbi Howard Cooper just published in the latest issue of the Jewish Quarterly. In ‘What is our security?’ Rabbi Cooper tells two stories. The first, drawn from a story he was told as a child, exemplifies how a relentless quest for security can produce precisely the opposite because it can be hard to bear the reality that ‘security’ – what it is, what we need in order to achieve it, where it comes from, and what we feel threatens us – is an internal experience.

The second story is from real life and concerns a young Jewish woman who was organizing a children’s Channukah event at a provincial arts centre where she worked, but who developed doubts about going ahead after a woman in a hijab, recently arrived in the UK from the Middle East, asked her whether the event was open to everyone. She consulted the CST, but even though she says they were ‘measured and reassuring’, she felt constrained to cancel the event. Rabbi Cooper writes:

This story – and it is not a parable – filled me with an immense sadness. I knew that this enlightened young woman had a sound understanding of how we unconsciously project onto others disowned feelings from within ourselves, and then feel ourselves threatened by those very feelings. If even she had succumbed to collective Jewish unease about Muslims, what hope was there for our collective well-being in the UK, when the community is led by by those with a less-psychologically-informed and more outwardly belligerent approach to questions about security?

He continues:

We are driving ourselves mad because of a spurious fantasy: that there is something called ‘security’ that we can achieve and possess. But feelings of ‘insecurity’ are psychological, spiritual, existential – such feelings can’t be eliminated by more of this chimera we name ‘security’.

Such is our post-Shoah concern with security that the original meaning of security in Hebrew, ‘trust in what we cannot see’, has become precisely the opposite, ‘trust in the power of our own hands’. Has the Jewish tradition to articulate a moral vision now finally come down to ‘Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition’, what seems to be the fundamental ethos of the religious settlers in the West Bank, he asks.

Rabbi Cooper concludes:

Perhaps to experience ‘security’ we need a renewed faith in aspects of ourselves that we Jews used to attribute to the Holy One of Israel: a capacity for compassion and reverence towards other human beings, a capacity to discern forms of idolatry that offer false security, a capacity to transmute anger into a passion for justice, and an enduring capacity for truth-telling that holds the impossible tension between love of the Jewish people and a responsibility to the ‘other’, the stranger, the outsider, who may never love us but whose well-being is still our concern.

Not only moving, but sound advice. Especially important, and sorely needed today and at all times, is ‘truth-telling’, with telling truth to power a fundamental priority. Alderman, Wittenberg and Cooper have taken very significant steps in this direction. The grandees of the community, the self-appointed guardians of our ‘security’ and the mainstream religious establishment should immediately take note. They already have a lot to answer for.