Albania – the only Nazi-occupied country where the number of Jews increased

It’s not a story that’s oft told. It doesn’t really fit in with the myth of the Judeo-Christian civilization that is peddled today. When the fundamentalists of Pastor John Hagee’s Christians United for Israel are the Zionists’ primary political supporters today and when Islam is held to be the enemy of civilisation and the West’s main threat, it is inevitable that the history of the holocaust will itself be distorted.

Yet the facts are quite clear. Muslim Albania was the only country in Nazi occupied Europe where the number of Jews actually increased – from 200 to around 2,000. Yad Vashem, the main holocaust memorial propaganda institute in Israel, which is responsible for their literary output, has a whole wall devoted to the minor war criminal, the Mufti of Jerusalem as if to emphasise Palestinian and Muslim complicity in the holocaust. It has yet to honour as ‘righteous among the nations’ a single Arab, despite the fact that the number of Jews who died in Nazi/Vichy occupied North Africa was about 1% of the Jewish population, compared to 90%+ for Poland and the Baltic countries.

|

| Albanian Jews |

Below are a number of articles, including from Yad Vashem, that paint a different story to the holocaust narrative that is predominant today.

Albanians saved Jews from deportation in WWII

Predominantly Muslim Albanians saved almost 2,000 Jews from deportation to the concentration camps during World War II. The family of US author Johanna Jutta Neumann was among those rescued.

“The Albanians were fantastic – after the war, there were even more Jews there than before,” Johanna Jutta Neumann said. During World War II, the Hamburg-born Jewish woman found refuge with a Muslim family in Albania. Less than 200 Jews lived in the small southeastern European country with a population of less than a million people before the war – and about 2,000 Jews called Albania home after World War II.

Today, Neumann, 83, lives in Washington, DC. The German-Albanian Friendship Association invited her to Germany to present her book Via Albania, in which she describes her family’s escape from Hamburg to Italian-occupied Albania in the spring of 1938. The Albanian Embassy in Berlin issued visas to Jews until 1942; as a result, until the summer of 1943 many European Jews applied to Albania for what was no longer possible anywhere else: asylum.

|

| A matter of honor – Book cover of Umweg über Albanien the German translation of Via Albania Copyright: DAFG Verlag Via Albania was translated into German |

In Albania, it is customary to offer guests (“mikut”) loyalty and hospitality – and guarantee their safety. Once an Albanian has given a guest his word, his “besa,” he must live up to it. It was this very tradition that contributed to giving Jews from throughout Europe safe refuge between 1938 and 1945 in Albania, a country with a predominantly Muslim population. The majority of the Jewish refugees lived in Albania until the early 1990s. After the fall of the Communist regime, many Albanian Jews emigrated to the United States and Israel.

The Israeli Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem has so far honored 69 Albanians as “Righteous among Nations,” an honor bestowed on people who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. Some of them were specially honored in the travelling exhibition “Besa: A Code of Honor,” first shown in 2008 at the United Nations headquarters in New York and now touring German cities, including Dresden, Görlitz and Leipzig.

|

| ‘Hall of Names’ in the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial EPA/JIM HOLLANDER |

Albanians saved Neumann’s family from deportation and extermination. At first they lived in a hotel – only to get acquainted with Albanian hospitality. “We left the hotel after about three months and moved in with a Muslim family,” Neumann said, adding that the Jewish family experienced their first Ramadan and Bairam festivals. “It was wonderful. People treated us like their own family.”

A safe haven

The fascist occupiers tried to deport Jews from Albania, too, but the population refused to surrender the Jews living in their country. Even members of the Albanian government pitched in, providing Jewish families with forged documents.

Many Albanian farmers took in and hid Jews. Anna Cohen’s family fled Thessaloniki and found refuge in the village of Tre Vllaznit, near Vlora.

“I was born in Albania shortly after the war ended, and I was raised there,” said Cohen, a New York dentist who left Albania for the USA in 1992. “I always felt like an Albanian of Jewish heritage.”

Albania was the opposite of other eastern European countries under Nazi occupation where Jews were concerned – Albania became their safe haven, according to Kiel-based historian and Balkans expert Michael Schmidt-Neke.

Between 1938 and 1945, more than 70 percent of the Albanian population was Muslim, the remaining 30 percent was Orthodox or Catholic. The ratio led to a great deal of interreligious tolerance, Schmidt-Neke said. The willingness to help persecuted Jews ran across the social, religious and political spectrum, he said, adding, “There were people who worked with the communist resistance that saved Jews as well as those who cooperated with the occupiers while they hid Jews in their homes.”

“Where Religious Prejudice and Hate Did Not Exist”[1]

Jews in Albania

Yael Weinstock Mashbaum

Introduction

In our last newsletter we addressed Jews from the southeastern European countries of Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Greece. While we in no way exhausted the topic, this issue focuses on the Jewish community of Albania, as the situation for Jews in this country during the Holocaust, is unique and even optimistic.

Almost all Jews in Albania during the Second World War were saved from Hitler’s “Final Solution.” This is remarkable and a circumstance that cannot be found in any other occupied country in Europe. How did this happen? Why was Albania good to its Jews?

|

| Albania, 1941, Buena Tova Rubenovic, Archival Number 5571/4Albania, 1941, Buena Tova Rubenovic |

|

| Berat, Albania, A House where Jews were Hidden, Archival Number 3793/3 |

History of Jews in Albania

A Jewish presence existed in Albania since the second century C.E. when a wave of Romaniote Jews immigrated to the north of the country. At the end of the 14th century, Romaniote Jews from Greece immigrated to Albania, with their unique customs and traditions. At the end of the 15th century during the Spanish Inquisition, the Turkish Sultan invited the Jews to live under Moslem rule in the Ottoman Empire and this brought Sephardic Jews to Albania. Though life for Jews was not always perfect, it proved to be a safe haven for centuries. Jews continued to emigrate from Greece in the 18th and early 19th centuries, arriving in Albania, settling in Vlora. Until World War II, the Jews of Albania maintained contact with the Jews of Ioannina and Corfu in Greece, and relied on these larger and more established communities to periodically provide a rabbi, cantor, and mohel (person who performs ritual circumcision) for their religious needs.

Before the 1930s some two hundred Jews lived in Albania. With Hitler’s rise to power and an increase in antisemitic activities, Jews felt threatened in their own countries,and began migrating from their homes in western and central Europe. By the outbreak of World War II, between six hundred and 1,800 refugees had arrived in Albania, from Germany, Austria, Serbia, Greece, and Yugoslavia, on their way to the United States, South America, Turkey, and Palestine. On the whole, Albania did not discriminate against its Jews. Due to Albania’s liberal visa application process, Jews began coming from all over Europe, and once the United States closed its door to them in 1938 and the Italians invaded in 1939, they realized that they would have to stay in Albania for the duration of the war. They did not realize at the time how lucky it was to have ended up there.

Italian Occupation

|

| Italian Soldiers Entering Durazzo, Albania, April 1939, Archival Number FA119/94Italian Soldiers Entering Durazzo, Albania, April 1939 |

When the Italians arrived in Albania they announced some anti-Jewish rules but the restrictions were not nearly as harsh or severe as those in German occupied countries. Jews were allowed to celebrate holidays and did not need to hide their identity. In Albania proper, Jews were not required to wear a “J” or “Jew” on their clothes (see Jewish Badge). However, life was different in the annexed territories such as Kosovo, which was brought under Albanian control in 1941. The Germans demanded that the Jews of Pristina be handed over to them. The Italians refused, but eventually agreed to hand over prisoners. Among the prisoners were sixty Jews, who were then murdered. Jewish refugees from other parts of Yugoslavia who had reached Pristina were transported to the older areas of Albania, where they were housed in a camp at Kavaje. Eventually some two hundred refugees were in this camp. The conditions there were poor, but the inmates could leave the camp during the day. About one hundred Jewish men from Pristina, later joined by their families were taken to Berat. In Berat, many were aided and protected by local Albanians. Smaller numbers of Jewish refugees could also be found in other localities, including the capital Tirana. Eventually, many of these Jews were turned over to the Nazis, and four hundred were shipped to Bergen-Belsen.

German Occupation

In September 1943, after the change in Italy’s government, Albania came under German control. The Germans requested a list of Jews living in Albania, and the Albanian government refused, reassuring the Jews that they would be protected in their country. However, this did not remove all potential danger from the Jews of Albania.

All around them Jews were being deported to concentration and death camps. In fact, the Jews of Vlora were almost wiped out when the Nazis prepared a list and planned to arrest them. However, that night the partisans came down to the city and began singing and dancing as a symbolic gesture of defiance. The Germans decided to depart that night, saving the lives of the Jews of Vlora.

The Righteous of Albania

Albania, the only European country with a Muslim majority, committed itself to saving all of its Jewish inhabitants. Almost all Jews living within Albanian borders during the German occupation, those of Albanian origin and refugees alike, were saved, except members of a single family. Ultimately, there were more Jews in Albania at the end of the war than before.

|

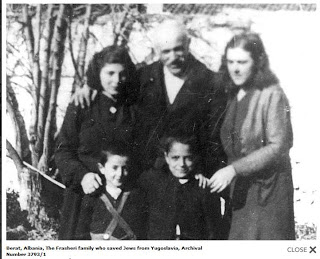

| Berat, Albania, The Frasheri family who saved Jews from Yugoslavia, Archival Number 3793/1Berat, Albania, The Frasheri family who saved Jews from Yugoslavia |

You can find more information on Albanians who have been recognized as Righteous Among the Nations, on the Yad Vashem website.

Teaching about Albania during the Holocaust

The story of Albanian Jews during the Holocaust is not complete without the story of the Albanians, both Muslim and Christian, who defied the Nazis and hid hundreds of Jews in their homes, preventing them from being murdered. This hospitality and heroism is worthy of discussion in the classroom.

In addition, many people are unfamiliar with the story of Albania during the Holocaust, and this country does not often arise when considering topics for educational purposes. However, teaching students about the geographic breadth that the Holocaust encompassed is important in helping them understand even further complexities about the period. It also expands their associations with the Holocaust, not limited to Germany, Poland, and concentration camps. On a lighter note, this is a happier story as the Jews were saved and people showed kindness and compassion to them. This is an excellent segue to the discussion of Righteous Among the Nations.

There are several resources that you may use in your classroom to develop this topic further:

Rescue in Albania by Harvey Sarner is a short book with a detailed look at the history of Albania and its Jews from the establishment of the community through the post-World War II era. I do not recommend assigning this book as reading, but an educator may lift pieces that relate to the topic at hand.

Yad Vashem’s exhibition called “Besa: A Code of Honor” discusses Muslim Albanians who rescued Jews during the Holocaust. Focusing on six Righteous Among the Nations, this online exhibit tells just a handful of stories of those who were saved and their rescuers.

The interview in this newsletter on the Romaniote Jews of Ioannina, Greece. Intertwined with photographs, this article with accompanying slides discusses the unique traditions of the Romaniote Jews, who also maintained a strong community in Albania.

Every place and every person tells their own story. Teaching the Holocaust from the perspective of countries in southeastern Europe undoubtedly teaches the complexities of the period. In the case of Albania, the situation was especially different than in any other country, both in the way Jews were treated and how they were welcomed in and saved. At a time when the world closed its doors, Albania extended its arm of hospitality. Even among the devastation and death, there were heroes and rescuers and this is important to teach as well.

[1] Quote by Herman Bernstein, the United States Ambassador to Albania, in 1934.

Jewish resistance in Albania

This article presents the unusual story of the very small Jewish community of Albania. The Jews of Albania were saved by the actions of the citizens of the country, mostly Moslems, who provided them with shelter and refuge.

The history of the Jewish community

The Jewish community of Albania existed within a Moslem country. The community was established in 1930, when several tens of Jews immigrated there from various Balkan countries. (Balkan is the historical, geographical name for the land which stretches across southeast Europe. This area is named for the Balkan Mountains which cross Bulgaria and Serbia). In the 1940’s another wave of Jewish refugees came from Greece, Macedonia, Croatia and Yugoslavia, in the wake of Nazi occupation. At the end of the war there were approximately 400 Jews in Albania, who were not permitted to leave since the country had become communist. In 1991, when the system of government changed, all 500 Albanian Jews made aliya to Israel.

During the Holocaust

In October 1940 parts of Albania were annexed to Italy. The Italians wanted to use its territory as a strategic base for the conquest of Greece. In September 1943, with the surrender of Italy, Albania was occupied by the Germans. After the Nazi occupation, the Jews of Albania found refuge in the homes of local families (most of them Moslems, and a few Christians) and with groups of partisans. Thanks to the solidarity evinced by their neighbors, all of the Albanian Jews were saved. Albanian Jewry was the only Jewish group in Europe whose numbers grew during the German occupation. Yad Vashem has recognized 63 Albanians as Righteous Among the Nations – a record number if one takes into account the number of Albanian inhabitants and the number of Jews who lived there. The fate of the Jews of Kosovo, part of Albania during WWII, was different. A company of S.S. operated there, their members recruited from among the local Albanians. The Jews were sent from there to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and to forced labor camps.

Albania and the Wannsee Conference report

In the report of the Wannsee Conference (a meeting which took place on January 20, 1942, where representatives of the Nazi government offices met in the Berlin suburb Wannsee), Albania appears on the list of countries whose Jews were destined for extermination in the Final Solution. The number of Jews listed in Albania was 200. This single line in the well-known document makes it clear that, in the German planning for the Jews, every Jewish community was included, every Jew to the last one.

Conclusion

During the war there were 803,000 inhabitants in Albania, of which 200 were Jews. Albania succeeded were other European countries failed. Most of the Jews who lived within her borders during the German occupation – several hundred Albanian Jews and Jewish refugees- were saved

Source: Balkan Holocausts, Steven Bauman – Yad Vashem website