Both Prussia and Israel were the product of a holocaust

Two years ago Uri Avnery, one of the few Zionists who you couldn’t describe as a racist, died. Avnery was a maverick Israeli who began his political life in Irgun, the fascist Revisionist Zionist militia and ended it as a fighter for peace.

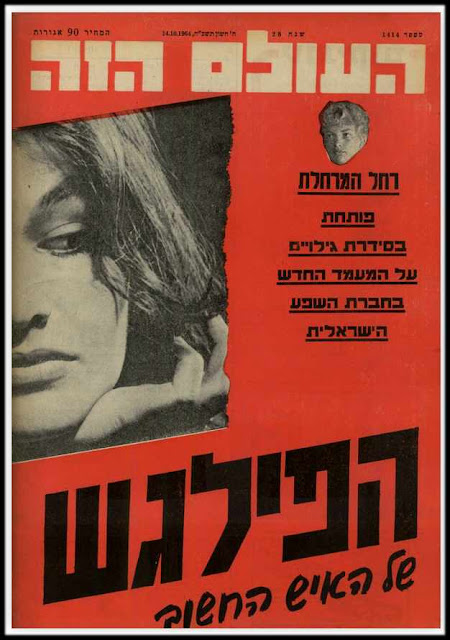

Avnery formed Gush Shalom, an Israeli peace group in 1993. He published for 40 years a muck raking magazine Haolam Hazeh that Ben Gurion hated so much that he refused to refer to it by name calling it ‘the filthy weekly’ or ‘the certain weekly’. Avnery was also a former member of the Knesset, serving three terms – 1965-1969, 1969-1973, 1979-1981, as well as being a prolific writer and columnist.

Avnery was lucky to survive a knife attack on him

When the PLO and Yasser Arafat were subject to a siege by the Israeli army in Beirut in 1982, Avnery crossed the armistice lines to meet him.Avnery is not the first person to draw attention to the comparison between Israel and Prussia. Both military states were by-words for the worship of the military and aggression. A good biography of Avnery is here.Take the test below and see how remarkable are the parallels between Israel and Prussia!

Tony Greenstein

Haolem Hazeh pictures Eichmann in the dock at Jerusalem

Uri Avnery12/12/09

A SHORT historical quiz: Which state:

(1) Arose after a holocaust in which a third of its people were destroyed?

(2) Drew from that holocaust the conclusion that only superior military forces could ensure its survival?

(3) Accorded the army a central role in its life, making it “an army that had a state, rather than a state that had an army”?

(4) Began by buying the land it took, and continued to expand by conquest and annexation?

(5) Endeavored by all possible means to attract new immigrants?

(6) Conducted a systematic policy of settlement in the occupied territories?

(7) Strove to push out the national minority by creeping ethnic cleansing?

For anyone who has not yet found the answer: it’s the state of Prussia.

But if some readers were tempted to believe that it all applies to the State of Israel – well, they are right, too. This description fits our state. The similarity between the two states is remarkable. True, the countries are geographically very different, and so are the historical periods, but the points of similarity can hardly be denied.

THE STATE that was respected and feared for 350 years as Prussia started with another name: Mark Brandenburg. (Mark: march, border area). This territory in the North-East of Germany was wrested from its Slavic inhabitants and was initially outside the boundaries of the German Reich. To this day, many of its place names (including Berlin neighborhoods, like Pankow) are clearly Slavic. It can be said: Prussia arose on the ruins of another people (some of whose descendants are still living there).

A typical Haolem Hazeh front cover

A historical curiosity: the land was first paid for in cash. The house of Hohenzollern, a noble family from South Germany, bought the territory of Brandenburg from the German Emperor for 400,000 Hungarian Gulden. I don’t know how that compares with the money paid by the Jewish National Fund for parts of Palestine before 1948.

The event that largely determined the entire history of Prussia up to World War II was a holocaust: the 30-years war. Throughout these years – 1618-1648 – practically all the armies of Europe fought each other on German soil, destroying everything in the process. The soldiers, many of them mercenaries, the scum of the earth, murdered and raped, pillaged and robbed, burnt entire towns and drove the pitiful survivors from their lands. In this war, a third of the German population was killed and two thirds of their villages destroyed. (Bertolt Brecht immortalized this holocaust in his play, “Mother Courage”.)

reading about the Eichmann trial in Haolem Hazeh

North Germany is a wide open plain. Its borders are unprotected by any ocean, mountain range or desert. The Prussian answer to the ravages of the holocaust was to erect an iron wall: a powerful regular army that would make up for the lack of seas and mountains and be ready to defend the state against all possible combinations of potential enemies.

At the beginning, the army was an essential instrument for the defense of the state’s very existence. In the course of time, it became the center of national life. What started out as the Prussian defense forces became an aggressive army of conquest that terrified all its neighbors. For some of the Prussian kings, the army was the main interest in life. For a time, the soldiers and their families constituted about a quarter of the Berlin population. An old Prussian saying goes: “Der Soldate / ist der beste Mann im Staate” – the soldier is the best man in the state. Adulation of the army became a cult, almost a religion.

A younger Avnery

PRUSSIA WAS never a “normal” state of a homogenous population living together throughout the centuries. By a sophisticated combination of military conquest, diplomacy and judicious marriages, its masters succeeded in annexing more and more territories to their core domain. These territories were not even contiguous, and some of them were very far from each other.

One of those was the area that came to give the state its name: Prussia. The original Prussia was located on the shores of the Baltic Sea, in areas that now belong to Poland and Russia. At first they were conquered by the Order of Teutonic Knights, a German religious-military order founded during the Crusades in Acre – the ruins of its main castle, Montfort (Starkenberg), still stand in Galilee. The German crusaders decided that instead of fighting the heathens in a faraway country, it made more sense to fight the neighboring pagans and rob them of their lands. In the course of time, the princes of Brandenburg succeeded in acquiring this territory and adopted its name for all their dominions. They also succeeded in upgrading their status and crowned themselves as kings.

The lack of homogeneity of the Prussian lands, composed as they were of diverse and unconnected areas, gave birth to the main Prussian creation: the “State”. This was the factor that was to unite all the different populations, each of which stuck to its local patriotism and traditions. The “State” – Der Staat – became a sacred being, transcending all other loyalties. Prussian philosophers saw the “State” as the incarnation of all the social virtues, the final triumph of human reason.

The Prussian state became proverbial. Demonized by its enemies, it was, however, exemplary in many ways – a well organized, orderly and law-abiding structure, its bureaucracy untainted by corruption. The Prussian official received a paltry salary, lived modestly and was intensely proud of his status. He detested ostentation. A hundred years ago Prussia already had a system of social insurance – long before other major countries dreamed of it. It was also exemplary in its religious tolerance. Frederick “the Great” declared that everyone should “find happiness in his own way”. Once he said that if Turks were to come and settle in Prussia, he would build mosques for them. Last week, 250 years later, the Swiss passed a referendum forbidding the building of minarets in their country.

PRUSSIA WAS a very poor country, lacking natural resources, minerals and good agricultural soil. It used its army to procure richer territories.

Because of the poverty, the population was thinly spread. The Prussian kings expended much effort in recruiting new immigrants. In 1731, when tens of thousands of Protestants in the Salzburg area (now part of Austria) were persecuted by their Catholic ruler, the King of Prussia invited them to his land. They came with their families and possessions in a mass foot march to East Prussia, traversing the full length of Germany. When the French Huguenots (Protestants) were slaughtered by their Catholic kings, the survivors were invited to Prussia and settled in Berlin, where they contributed greatly to the development of the country. Jews, too, were allowed to settle in Prussia in order to contribute to its prosperity, and the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn became one of the leading lights of the Prussian intelligentsia.

When Poland was divided in 1771 between Russia, Austria and Prussia, the Prussian state acquired a national minority problem. In the new territory there lived a large Polish population that stuck to its national identity and language. The Prussian response was a massive settlement campaign in these areas. This was a highly organized effort, planned right down to the minutest detail. The German settlers got a plot of land and many financial benefits. The Polish minority was oppressed and discriminated against in every possible way. The Prussian kings wanted to “Germanize” their acquired areas, much as the Israeli government wants to “Judaize” their occupied territories.

This Prussian effort had a direct impact on the Jewish colonization of Palestine. It served as an example for the father of Zionist settlement, Arthur Ruppin, and not by accident – he was born and grew up in the Polish area of Prussia.

IT IS impossible to exaggerate the influence of the Prussian model on the Zionist movement in almost all spheres of life.

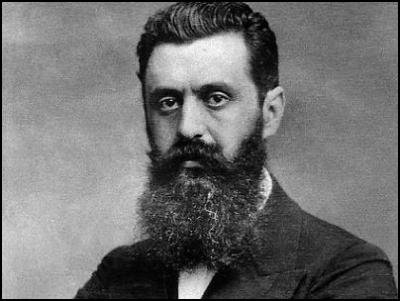

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl, the founder of the movement, was born in Budapest and lived most of his life in Vienna. He admired the new German Reich that was founded in 1871, when he was 11 years old. The King of Prussia – which constituted about half of the area of the Reich – was crowned as German emperor, and Prussia formed the new empire in its image. Herzl’s diaries are full of admiration for the German state. He courted Wilhelm II, King of Prussia and Emperor of Germany, who obliged by receiving him in a tent before the gate of Jerusalem. He wanted the Kaiser to become the patron of the Zionist enterprise, but Wilhelm remarked that, while Zionism itself was an excellent idea, it “could not be realized with Jews”.

Herzl was not the only one to imprint a Prussian-German pattern on the Zionist enterprise. In this he was overshadowed by Ruppin, who is known today to Israeli children mainly as a street name. But Ruppin had an immense impact on the Zionist enterprise, more than any other single person. He was the real leader of the Zionist immigrants in Palestine in their formative period, the years of the second and third Aliyah (immigration wave) in the first quarter of the 20th century. He was the spiritual father of Berl Katznelson, David Ben-Gurion and their generation, the founders of the Zionist Labor movement that became dominant in the Jewish society in Palestine, and later in Israel. It was he who practically invented the Kibbutz and the Moshav (cooperative settlement).

If so, why has he been almost eradicated from official memory? Because some sides of Ruppin are best forgotten. Before becoming a Zionist, he was an extreme Prussian-German nationalist. He was one of the fathers of the “scientific” racist creed and believed in the superiority of the Aryan race. Up to the end he occupied himself with measuring skulls and noses in order to provide support for assorted racist ideas. His partners and friends created the “science” that inspired Adolf Hitler and his disciples.

The Zionist movement would have been impossible were it not for the work of Heinrich Graetz, the historian who created the historical image of the Jews which we all learned at school. Graetz, who was also born in the Polish area of Prussia, was a pupil of the Prussian-German historians who “invented” the German nation, much as he “invented” the Jewish nation.

Perhaps the most important thing we inherited from Prussia was the sacred notion of the “State” (Medina in Hebrew) – an idea that dominates our entire life. Most countries are officially a “Republic” (France, for example), a “Kingdom” (Britain) or a “Federation” (Russia). The official name “State of Israel” is essentially Prussian.

WHEN I first brought up the similarity between Prussia and Israel (in a chapter dedicated to this theme in the Hebrew and German editions of my 1967 book, “Israel Without Zionists”) it might have looked like a baseless comparison. Today, the picture is clearer. Not only does the senior officers corps occupy a central place in all the spheres of our life, and not only is the huge military budget beyond any discussion, but our daily news is full of typically “Prussian” items. For example: it transpires that the salary of the Army Chief of Staff is double that of the Prime Minister. The Minister of Education has announced that henceforth schools will be assessed by the number of their pupils who volunteer for army combat units. That sounds familiar – in German.

After the fall of the Third Reich, the four occupying powers decided to break up Prussia and divide its territories between several German federal states, Poland and the USSR. That happened in February 1947 – only 15 months before the founding of the State of Israel.

Those who believe in the transmigration of souls can draw their own conclusions. It is certainly food for thought.

See also a similar essay by Uri Avnery The Settlers’ Prussia

The 30 year war saw the death of up to 8 million people

Ending the new Thirty Years war

New Statesman January 2016

Why the real history of the Peace of Westphalia in 17th-century Europe offers a model for bringing stability to the Middle East.

By Brendan Simms and Michael Axworthy and Patrick Milton

A man hangs upside down in a fire. Others are stabbed to death or tortured; their womenfolk offer valuables to save their lives – or try to flee. Elsewhere, women are assaulted and violated. In another image the branches of a tree are weighed down with hanging bodies, and a religious symbol is proffered to a victim as the last thing he will see on Earth. The caption describes the hanged men as “unhappy fruit”.

This could be Syria today: but it is Europe, in the mid-17th century, at the height of the Thirty Years War. The artist who recorded these horrors was Jacques Callot, who saw the French army invade and occupy Lorraine in 1633. He was perhaps the closest thing his time had to a photojournalist.

The Thirty Years War, within which the occupation of Lorraine was just a short episode, has been cited as a parallel in new discussions of the Middle East by a range of foreign policy practitioners, including Henry Kissinger and the president of the US Council on Foreign Relations, Richard Haass, academics such as Martin van Creveld and journalists such as Andreas Whittam Smith. Like the original Thirty Years War, which was in fact a series of separate but interconnected struggles, recent conflict in the Middle East has included fighting in Israel, the occupied territories and Lebanon, the long and bloody Iran-Iraq War, the two Gulf wars, and now civil wars in Iraq and Syria. As with the Thirty Years War, events in Iraq and Syria have been marked by sectarian conflict and intervention by peripheral states (and still more distant countries) fighting proxy wars. Both the Thirty Years War and the present Middle Eastern conflicts have been hugely costly in human life. The Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years War in 1648 has also featured in comment of late, usually along with the observation that recent events have brought about the collapse, at least in parts of the Middle East, of ideas of state sovereignty that supposedly originated with Westphalia.

Yet that is a myth, a serious and perhaps fatal misunderstanding of the Westphalian treaties. The provisions of the treaties in fact set up a structure for the legal settlement of disputes both within and beyond the German statelets that had been the focus of the conflict, and for the intervention of guarantor powers outside Germany to uphold the peace settlement. And, as we shall see, the real history of Westphalia has much to tell us in the present about the resolution and prevention of complex conflicts.

***

Germany is the prosperous heart of the continent today, but in the early 17th century the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation” was the disaster zone of Europe. It was politically fragmented, with the various princes, bishops, towns and the emperor himself all vying for influence, greatly complicated by religious differences between Roman Catholics and followers of various forms of Protestantism. The empire lay at the centre of Europe and was thus the point at which the great-power interests of nearly all the main protagonists in the international system intersected: the French, the Habsburgs, the Swedes, the Ottomans and even the English regarded the area as vital to their security. So Germany both invited intervention by its neighbours and spewed out instability into Europe when the empire erupted in a religious war in 1618 that lasted three decades.

Domestically, the root of the Thirty Years War, just as with many Middle Eastern conflicts today, lay in religious intolerance. The security of subjects governed by rulers of the opposing religious camp was often at risk of their governments’ attempts to enforce doctrinal uniformity. With the creation of cross-border confessional communities, as well as antagonisms both within and between the territorial states, rulers became increasingly willing to intervene on behalf of co-religionist subjects of other princes – another parallel with the contemporary Middle East.

Initial attempts to solve these problems failed. After a series of wars following the Reformation, a religious peace was concluded at the imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1555. This was a milestone in the development of confessional cohabitation, because it embodied, for the first time, a recognition of the importance of creating a legal-political framework to manage religious coexistence. Although the treaty helped foster peace for many years, it was nevertheless deficient. First, the princes granted each other toleration only between themselves, not among subjects within their territories. The “Right of Reformation”, or ius reformandi, gave princes the power to impose their confession on their subjects: a form of religious compulsion later encapsulated in the phrase cuius regio, eius religio (“the religion of the prince is the religion of the territory”).

Rulers became increasingly willing to intervene on behalf of co-religionist subjects of other princes

This was a state-centred solution; it ignored the concerns of the princes’ subjects apart from guaranteeing their right to emigrate. Partly designed to undercut interventionist impulses by consigning confessional affairs to an inviolable domestic sphere, the treaty text stated: “No Estate [territory] should protect and shield another Estate or its subjects against their government in any way.” Second, the state-centred settlement was increasingly unsatisfactory for most Protestant states, as it had inbuilt structural advantages for the Catholic side. Calvinism was not recognised and remained officially a heresy. Furthermore, the Catholic princes began to rely on majority voting to sideline Protestants at decision-making assemblies such as the Reichstag or Diet, which in effect was the German parliament. And the Catholic Church embarked on a major evangelising effort to reverse the effects of the Protestant Reformation through popular preaching – the Counter-Reformation, a prime mover for which was the Jesuit order. Taken together, these factors left Protestants feeling increasingly under pressure, and more radical Protestants were constantly trying to revise the settlement. The formation of hostile princely religious alliances – the Protestant Union in 1608 and the Catholic League in 1609 – was symptomatic of the general “war in sight” atmosphere characterising central Europe at the turn of the 17th century.

The resulting war was, just like the current Middle Eastern conflict, a set of interlocking political-religious struggles at local and regional levels. These provoked and enabled extensive external interference, which in turn exacerbated and prolonged the conflict. Non-state and sub-state actors played important roles in that epoch as they do now: corporate groupings of noble subjects (estates) and private military entrepreneurs; terrorist groups and aid organisations. The war began as an insurrection of the Bohemian nobility against their Habsburg rulers, and soon escalated into a much broader confessional conflict within the empire. But it also became a struggle between competing visions of the future political order in central Europe – a centralised imperial monarchy against a more federally organised, princely and estates-based constitution – which in turn folded into the long-standing Habsburg-Bourbon struggle for European supremacy.

The war was immensely destructive: arguably the greatest trauma in German history. It resulted in an overall loss of about 40 per cent of the population, which dropped from roughly 20 million to 12 million. The war was not merely quantitatively, but qualitatively, extreme. Such atrocities as the massacre and burning of Magdeburg in 1631, which killed over 20,000 people, resonate in the German popular imagination to this day. The war also caused its own refugee crisis. Cities such as Ulm hosted huge numbers relative to their pre-war population – 8,000 refugees taken in by 15,000 inhabitants in 1634, a situation comparable to the one faced by Lebanon today, where one in four people is a Syrian refugee. The resulting shifts in the religious balance often sparked unrest in previously quiet areas, a phenomenon we are beginning to see in the Middle East as well. In those days no one had come up with the concept of toxic stress – but the trauma was no less for that.

***

Eventually, the war between the Holy Roman emperor, the princes, Sweden, France and their respective allies was brought to an end by the now-famous Treaties of Münster and Osnabrück (collectively known as the Peace of Westphalia). In roughly the past century and a half, however, their nature and implications have been completely misunderstood. The misconception – still frequently repeated in many textbooks, in the media, by politicians, and in standard works on international relations – maintains that the Peace, by granting the princes sovereignty, inaugurated a modern “Westphalian system” based on states’ sovereign equality, the balance of power and non-intervention in domestic affairs. This fallacious notion of Westphalia was later picked up uncritically by political scientists, scholars of international law and historians, leading to the remarkably persistent and widespread Westphalian myth.

The real Westphalia was something quite different. Although the Right of Reformation was officially confirmed, it was in effect nullified by the imposition of the “normative year”. This fixed control of the churches, the right of public worship, and the confessional status of each territory to the state it had been in, on 1 January 1624. This was an innovative compromise arrangement that set a mutually acceptable official benchmark for faith at a point in time at which neither side had gained supremacy. By establishing a standard applicable to all, it also represented a convenient means of avoiding the conflicts of honour inherent in early-modern negotiations in which princes were asked to make concessions.

The practical outcome was that a princely conversion could no longer determine the religious affiliation of the subject population in question. The imperial judicial tribunals retained extensive authority to enforce the confessional and property rights of princes’ subjects (many of which were stipulated at Westphalia). The external guarantors, France and Sweden, were granted a right to intervene against either the emperor or the princes, in order to uphold Westphalian rights and terms. So, this “true Westphalia” is better characterised as an order of conditional sovereignty.

Princes were entitled to rule for life, but crucially were required to respect their subjects’ basic rights, such as religious freedom (including that of Calvinists), enjoyment of property and access to judicial recourse, while also respecting the rights of fellow rulers. If they failed in their duties towards their subjects or the empire they could in theory and practice become targets for intervention, which in some cases entailed deposition from power.

That central Europe avoided another religious war after 1648 shows the success of Westphalia’s conflict regulation mechanisms. At a time of renewed religious dispute in the early 18th century, a statement issued by the Protestant party at the imperial Diet commented on the improvements that Westphalia had brought to the imperial constitution, stating: “The refusal of Territorial rulers to accept that other fellow states protect foreign inhabitants and subjects was one of the greatest causes which led to the wretched Thirty Years War. It is precisely this wound which has been healed by the Peace of Westphalia.”

Westphalia was thus seen as a corrective measure, opening up domestic affairs to mutual and reciprocal scrutiny, on the basis of clear principles agreed by all. It provided an effective system for the “juridification” of conflict, whereby confessional strife (which certainly continued) was channelled into a legal-diplomatic framework and defused through litigation and negotiation, if necessary with the threat of external intervention by a guarantor power, rather than being settled by warfare.

***

Where in 17th-century Europe Protestants were alarmed by the revanchism of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, through which the emperor (with the support of his Spanish Habsburg cousins) sought to restitute property and lands confiscated from the Catholic prince-bishoprics by Protestant princes during the previous century, so in the Middle East today Shia communities feel under pressure from the new wave of aggressive Wahhabi/Salafi jihadism which similarly regards their faith as heresy and abomination. Or, if you choose to accept the Saudi or Wahhabi version, you could regard Iran and the Shias as the threatening hegemon. One way or the other, both Iran and Saudi Arabia feel insecure in the region, menaced by enemies, to a degree paranoid and liable to miscalculate the true nature of the threat to them and their faiths.

Moreover, the position can change. After the Swedish intervention in Germany in 1630, the Catholics, previously triumphant, were thrown on the defensive and their worst nightmares began to come true. For an eventual settlement to become possible, it was necessary for disillusionment with religious aggrandisement to set in. That might still seem to be some way off in Syria and Iraq now; yet perhaps not so far off. At an earlier stage some Sunnis at least, in Iraq and elsewhere, became disillusioned with al-Qaeda when it was seen to be able to offer no more than continuing violence, with no prospect of any kind of victory. It will be necessary first to defeat Da’esh, or Islamic State, but disillusionment with it could set in quite quickly when its millenarian project is seen to suffer severe setbacks. It will nonetheless be necessary to deal with the Wahhabi origins of the jihadi problem, in Saudi Arabia, as Michael Axworthy argued in his New Statesman article of 27 November 2015.

It would be highly desirable as part of a wider Westphalia-style settlement also to make progress towards a solution of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. Yet such a settlement should not be seen as necessarily dependent on that. The Israel/Palestinian question is not an important factor in the present situation in Syria or Iraq, nor has it been among the prime concerns of al-Qaeda or Islamic State, which have both been much more focused on toppling Arab states in the Middle East.

Another aspect of the conflict in the Middle East is that both Iran and Saudi Arabia see themselves as the legitimate leader of the community of Islam as a whole. Just as Christendom was pulled apart by religious conflict in the 17th century, yet Catholicism and Protestantism were still horribly bound together, like cats in a sack, by a shared history and shared faith, so too with contemporary Islam. The traditional territory of Islam is still, in some sense, a coherent whole in the minds of Muslims. In a way reminiscent of that in which the Holy Roman emperor’s authority was still recognised by the Protestant states of the empire, albeit reluctantly and with bitter resentment, so Shia Muslims have to accept Saudi Arabia’s de facto guardianship of the holy places of Medina and Mecca. A settlement in the Middle East could take strength from the lingering sense of a common heritage in the region.

***

The creation of Iraq, Syria and Lebanon as sovereign states after the First World War owes something to the European state model that is linked in the minds of many to the mythical Westphalia. Some would say that the model was artificial and unsuited to the complex political reality of those countries; that the continuing collapse of Iraq and Syria (with Lebanon looking fragile) is at least in part a consequence of the bad match. But it may be less the borders of those states that have been the problem than the internal political nature of the states as they were established.

The new nations’ borders for the most part followed the boundaries of previous Ottoman administrative districts, including those abolished with much fanfare by Islamic State 18 months ago. Such is the ethnic, religious and tribal complexity of the peoples they contain that they are likely to be difficult to divide up in any less artificial or more satisfactory way. Any attempt to redraw borders extensively is likely to deepen and exacerbate the chaos. In the Westphalia settlement, with only a few exceptions, the pre-war borders of the German statelets were retained; it was the way the states related to each other and the confessional diversity of their subjects that changed. There is a lesson here.

Sectarianism, the interference of neighbouring states, the breakdown of earlier state arrangements, the exodus of refugees –all of these are features of a region that has become, as a recent New Statesman leader put it (quoting Karl Kraus), a “laboratory for world destruction”. Some in the contemporary Middle East are aware of past religious extremism and conflict in Europe and ask how we overcame it historically. Therefore, it is in no way patronising to offer the lessons of those past traumas: it is part of our shared human experience, our collective memory. That is what history is – or can be. The Westphalia myth, in supporting a notional model of the modern state which has failed in both Iraq and Syria, may have contributed to the terrible conflicts we have seen unfolding in recent years in those countries. The real Westphalia, by contrast, could contribute to a solution.

It showed ways to turn interference in wars into guarantees of peace.

Its application to the Middle East requires an inclusive conference with representatives from all recognised states in the region, plus potential “guarantor” powers. The negotiations would have to start from the assumption that the “truth content” of the various positions has to be set aside for now, and would have to end with a recognition that sovereignty would be conditional and involve the transfer of some prerogatives to common institutions modelled on the old German imperial supreme judicial institutions and/or the Reichstag. Populations would not necessarily be guaranteed democratic participation in the first instance, but governments would be obliged to respect certain vital rights, including the free exercise of religion and, in certain circumstances, that of judicial appeal outside their local jurisdictions. Toleration would thus be “graded”, Westphalian-style, with the recognition of a dominant religion or system in each territory, but with safeguards for minorities. As with Westphalia, rulers would be constrained by duties towards their own subjects (for that is what they are, at present), but also towards respecting each other’s integrity as well as that of the whole system. The whole arrangement would then have to be placed under external guarantee of agreed regional and global powers.

All this requires political will and engagement, obviously, but it must begin with some intellectual legwork. To this end, the Forum on Geopolitics at the University of Cambridge has established a “Laboratory for World Construction”, drawing on expertise in both cases, to begin to design a Westphalia for the Middle East.

***

There will be no a “quick fix”; the Westphalia negotiations took five years and ultimately failed to end the related war between Spain and France (which lasted until 1659). By 1648 the various warring parties in central Europe had reached a state of general exhaustion, and disillusionment with religious extremism.

But the lessons of the real treaties of Westphalia, which provided means for the legal resolution of disputes and showed ways to turn external interference in conflict into external guarantees for peace, could be a significant contribution to eventual settlement of the Middle East’s problems.

Bringing peace to the Middle East will not be easy, and many have failed before. Yet if it could be done in mid-17th-century Germany, a problem no less intractable, then anything is possible.

Brendan Simms is the director of the Forum on Geopolitics at Cambridge

Michael Axworthy is the director of the Centre for Persian and Iranian Studies at the University of Exeter

Patrick Milton is a postdoctoral fellow at the Free University of Berlin (POINT programme) and co-ordinator of the Westphalia for the Middle East “Laboratory for World Construction” at the Forum on Geopolitics