What happened when, as part of an experiment, Arab youth joined Kibbutzim?

When faced with the contradiction between Socialism and Zionism the dilemma was always resolved in favour of the latter

When I was young Israel was seen by many on the Left as a socialist oasis in the Middle East. Until 1977, Israel was ruled continuously by Israeli Labour/Mapai coalitions, sometimes in alliance with Mapam, the United Workers Party that was to the left of Mapai. Nearly all land in Israel was nationalised and the trade union Histadrut was the second major employer after the state itself.

The Fabians waxed lyrical about Israeli ‘socialism’. Many were the times when I was told to go to Israel if I wanted to see socialism and join a Kibbutz. However there were also many things that we were not told such as the fact that Israel’s Arabs lived under military rule from 1948 to 1966.

The Kibbutzim were collective settlements where members shared everything in common. Of course the Kibbutzim operated in the context of a market economy so they did not affect the society around them. But what we were not told was that they were Jewish only institutions of which Arabs could not be members, since the land they occupied was ‘national’ i.e. Jewish national land

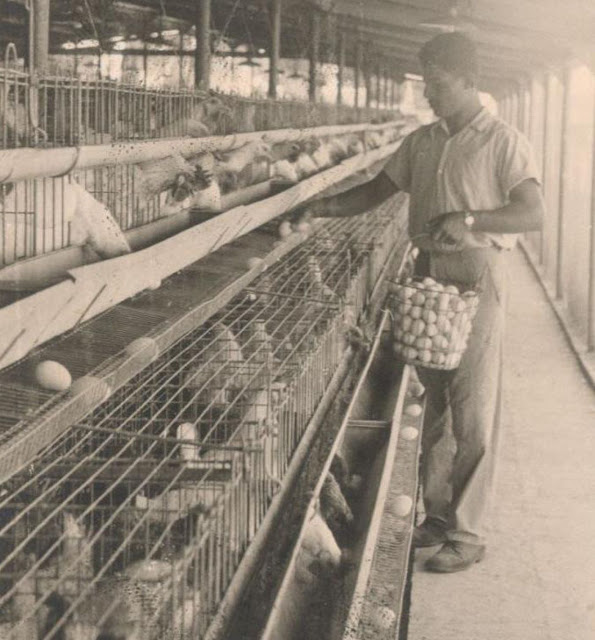

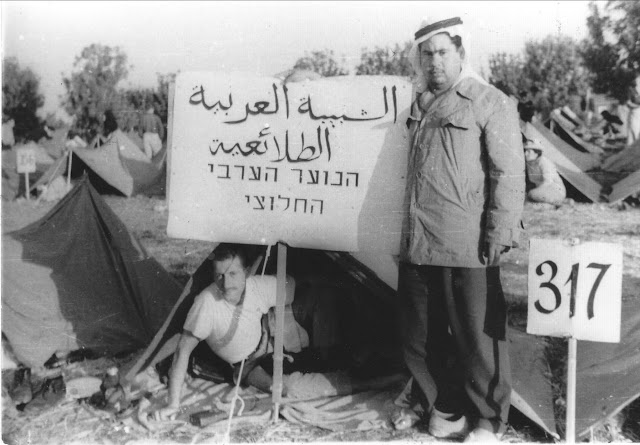

Ahmad Masrawa, left, on Kibbutz Yakum

What we were also not told was that the Kibbutzim had taken over vast stretches of the land of the Palestinians who had been expelled from Israel or who were ‘internally displaced’ within Israel. These were present-absentees in the Orwellian terminology of the 1950 Absentee Property Law. Even though they had not left Israel in 1948 and even if they were expelled from their homes, they were not allowed to go back to them. They are present yet absent.

But what we were also told was that the Palestinian refugees had voluntarily left in order that the Arab armies could invade. They had been instructed to do so by broadcasts from Arab radio stations. This fable turned out to be a myth cultivated to justify not allowing the refugees to return.

Erskine Childers and Rashid Khalidi conducted independent research in 1961 examining the transcripts of the CIA and BBC monitoring stations in the Middle East. They recorded no instances of such Arab broadcasts. Childers published an article about this in the Spectator of 12 May 1961 and Christopher Hitchens covers this in his book Blaming the Victims.

Mapam traced its ideological origins to Ber Borochov, who considered himself a Marxist Zionist. He was expelled in 1901 from the Russian Social Democratic Party. He believed that Jews in the Diaspora could not wage class struggle because they constituted an inverted pyramid, too many were rich and not enough were workers. They therefore had to form their own society in Palestine. Why Palestine? No clear answer was given but it would seem that Zionism based its claims on the god that they denied existed!

Mapam thus embodied the contradictions of those who believed they could reconcile Zionism and socialism. Although they were active participants in Zionist settler colonialism they believed this could be reconciled with the socialist concept of the brotherhood of man. Although they drifted from their pro-Soviet views they still saw themselves as embodying socialist Zionism whereas Mapai had never made a pretence of being a socialist party.

Originally Hashomer Hatzair, which gave birth to Mapam, believed in a bi-national state but in 1948 they were the leaders of the Palmach shock troops which committed some of the worst atrocities such as at Duwayma.

The articles below, in Ha’aretz and by Jonathan Cook, describe what happened when 2 members of Mapam, successfully argued that Mapam kibbutzim should put into practice their socialist beliefs. Mapam’s slogan was Zionism, socialism and the brotherhood of nations.‘Zionism’ was deliberately placed before ‘socialism’ because whenever there was a contradiction between one and the other it was socialism which gave way.

Mapam had its own Kibbutz Federation Ha Kibbutz Ha’artzi and these kibbutzim had been equally aggressive as the other Labour kibbutzim in grabbing and settling confiscated Arab land. The famous cases of the Arab villages of Ikrit and Birim, whose inhabitants had been persuaded to leave their lands on the promise of being able to return once hostilities had ended in 1948 demonstrate their hypocrisy.

It was the Mapam Kibbutzim of Baram and Sasa which occupied the lands of Bir’im and Ikrit and they had no intention of giving them back! Despite Israel’s Supreme Court ruling in favour of the return of their inhabitants, the Israeli army demolished the village of Ikrit on Xmas Day 1951 and in 1953 the same happened in Bi’irim. As Golda Meir stated

‘it is not only consideration of security [that prevent] an official decision regarding Bi’rim and Iqrit, but the desire to avoid [setting] a precedent. We cannot allow ourselves to become more and more entangled and to reach a point from which we are unable to extricate ourselves.’

The precedent she was referring to was that of allowing villagers who had been expelled to return to the same lands. This same ‘dilemma’ was to revisit Mapam as we shall see.

Aharon Cohen, had been sufficiently moved by the commitment to socialism and brotherhood that they had persuaded other members of Mapam to engage in an experiment whereby hundreds of Israeli Arabs, who were legally forbidden to leave their villages by the military, formed an Arab Pioneers group and became part of these kibbutzim, albeit not full members

Zionism is a movement whose aim is to establish a Jewish state and the obvious contradiction was that here were Arabs who were being trained to be Zionists and loyal to a State which consciously excludes them. The same is true of Druze leaders in Israel today who believe that they have a part to play in the ‘Jewish’ state. They were sadly disillusioned by the Jewish Nation State Law.

Fundamental to establishing a Jewish state was the dispossession of the natives. The Kibbutzim were established over the ruins of the Palestinian villages that they had razed to the ground.

What happened has been turned into a film ‘I used to be Zvi’. The contradictions were many and they were insuperable. They were summed up by Mapam’s use of two flags – the red flag of socialism and the blue and white flag of Zionism. Zionism stands for a Jewish society and socialism for unity of the working class. You cannot be exclusivist and universalist. It is a contradiction that no clever formulations can gloss over.

The film tells the story of Ahmad Masrawa who left his village to join Kibbutz Yakum. It ends with him joining Matzpen, the anti-Zionist socialist organisation, after the 6 day war when Mapam, as enthusiastically as any of the Zionist parties, supported the war.

Most of the Arabs who took part were eager to join the Kibbutzim. It was an escape from the poverty of their villages. At its height in 1960 over two thousand took part in this experiment, in defiance of the Military Rule which confined Arabs to their villages. As the articles pointed out there was real hunger in the Arab villages. They were forbidden to till their lands which had been confiscated by the same Kibbutzim.

There was also a desire by Israel’s Arabs to become part of state which would not have them. This desire by Israeli Arabs to integrate into the Israeli state is still there but they are not, of course, allowed to do so by a state which is racially ‘Jewish’. Materially Israeli Arabs are better off in Israel despite the ingrained racism and their pariah status.

In a recent opinion poll for +972 Magazine just 14% of Israel’s Arabs identify as Palestinian and another 19% as Palestinian Israelis compared to 22% who see themselves simply as Arabs and 46% as Israeli Arabs.

There were also differences within the supposedly equal kibbutz society between these Arab newcomers and the existing Jewish members. Masrawa relates how:

The Arab youths worked five hours a day and studied for three hours, while the Jewish “outside children” had the opposite schedule. “I had the chutzpah to ask why, and I was told that the Jews were subsidized by Youth Aliyah.’

The article describes how the village of Arara where Mahmoud Younes came from had seen its lands reduced from 36,000 to barely 1,500 dunums. This naked land theft was part of Zionism’s ‘redeeming’ of the land. So when the Arabs who had come to the Kibbutzim wanted to set up an Arab kibbutz, they were reminded by the Jewish Agency that the land on which they wanted to set up was Jewish national land. An Arab kibbutz was impossible and thus we learn the first contradiction of this experiment. It was impossible to escape what a Jewish State meant in practice. There would be no possibility of equality within a state based on one ethnicity.

Atallah Mansour, who became very much the tame acceptable Arab and a journalist in the Zionist press, stated that “the kibbutz is a solution for Jews only. Anyone who isn’t a Jew but just a human being who wants to live and work, has no place there.” This was the dilemma that the founders of this experiment could not overcome.

As Walid Sadik, who later became a member of the Knesset put it, ‘the coexistence was forced, not genuine. Coexistence is expressed in everyday life, in deeds, not in theories.’ The Zionists wanted their supremacy at the very same time as they wanted their consciences eased – to have their ‘socialism’ and their Zionism live side by side in harmony. As Mansour put it ‘We were equal in principle, but we weren’t treated as equals for even one day’.

However the real difficulty came with personal relationships. Not surprisingly, despite the taboo against Jewish and Arab relationships, some personal relationships formed and these caused the most problems.

It is impossible for a Jewish only society, which is what Kibbutzim are, to accept that Arabs married to Jews can become full members. It is socially accepted throughout Jewish Israel that Jews and Arabs don’t marry or have sexual relations because it is necessary to keep a distance between the Jews of a Jewish state and the Arabs. States based on race need strict boundaries.

The example of Tzvia Ben Matiyahu from Kibbutz Givat Hashlosha and Rashid Jaffer Masarawa epitomised this ‘dilemma’. To have a member of the superior race fall in love with the untermenschen is a threat to the concept of a Jewish state. Tzvia ‘couldn’t believe that the kibbutz she loved so much wouldn’t accept the love affair, but Rashid understood the problem immediately.’ In a racially separate society, miscegenation is frowned upon and legislated against.

The couple had to leave Kibbutz Hashlosha. Because civil marriage isn’t possible in Israel they had to get married in Cyprus. They began to live in Hadera, a Jewish town, but the racism of their fellows made their lives unbearable, so they applied to live in the Mapam Kibbutz of Gan Shmuel.

How then did these socialist Zionists deal with the ‘problem’ of an Arab married to a Jew? Well at the Kibbutz Assembly ‘someone mentioned that I was from Sarkas.’ Sarkas was the village whose land Gan Shmuel had confiscated. One might think that socialists would be only too eager to accept the couple by way of restitution for previous crimes. Not a bit of it.

The person who revealed his parentage ‘argued that if I was accepted as a member, it would mean that I was being returned to my village.” What could be worse than the Return of an Arab to his lands, albeit as part of a Kibbutz? If Jews ‘return’ to a land they had never been a part of, then that is fine. But for an Arab to return is unacceptable. The reality is that the Kibbutzim were always collective colonists. The idea that the indigenous population might join them and obtain satisfaction from the land that was stolen from them was too much.

“It was a tremendous drama, possessing ideological dimensions,” was how Ran Cohen, later a Meretz MK, recalls.

“The agonizing was real. The opponents said: ‘The kibbutz is a Zionist body that is situated on Jewish National Fund land, so why would we ever want to settle Arabs on it?’ There was also a social aspect. After all, the kibbutz is a Jewish entity with Jewish holidays, customs and culture. How would an Arab fit in?

There is a lot of truth in this. Kibbutzim are set up on Jewish national land, owned by the JNF, whose very constitution specifically says it is for the benefit of Jews.

To Tzvia, who was born on the Kibbutz, this was all a shock. It is interesting that ‘Tzvia likened her story to that of kibbutz girls who had fallen in love with an Iraqi or Moroccan Jew.’ The Kibbutzim were also bastions of racism against Arab Jews. Tzvia’s ‘world collapsed’. She told Haolem Hazeh, that she grasped that

“it was prohibited for someone to join the kibbutz – not because he’s unsuitable, not because he’s an idler, not because he’s maimed or uneducated, but because he was born an Arab! Even the kibbutz, this beautiful fruit, is being eaten away by the worm of racism.”

None of these things had ever been explicitly spelt out to Tzvia. They had been taken for granted. Also as the article says, after 1967 western volunteers flocked to the Kibbutzim. There was no longer a need for Arab labour which suggests that behind the idealism of Cohen and Tsur there were also economic motives, viz. that the Arab Pioneers were a source of cheap Arab labour.

Masarawa asked his Jewish kibbutzniks to ‘Explain to me how Zionism and socialism go together.’ And described how‘

they threw sand in our eyes. They made a mockery of the ideal. They played with lofty ideas, but in practice they behaved otherwise.’

He summed it up as ‘The kushi [nigger] has done his duty, the kushi can go’

Shaul Paz describes the Pioneering Arab Youth as

“a fascinating, astounding, short-lived experiment that disappeared from memory. With it disappeared our dreams, aspirations and illusions that a different Israel was possible.”

It is true that many Zionists had a dream that a different Israel was possible. Many saw themselves as genuine socialists. Some even went to fight in the Spanish Civil War for the Republicans. Yet despite these good intentions, the logic of Zionist colonisation asserted itself.

A Jewish state is by definition an inherently racist state and even those professing to be socialists could not change the reality in which they lived.

As Jonathan Cook put it in respect of the decision of Kibbutz Gan Shmuel to reject the young couple,

‘The Zionism of these Jewish socialists decisively trumped any semblance of shared humanity or compassion. The Pioneer Youth dissolved soon afterward as young Palestinians in Israel shifted allegiance towards the new Arab nationalism of Nasserist Egypt.

When Arabs Were Invited to Live the Zionist Dream

In Israel’s first decades hundreds of young Arabs left their villages to work on kibbutzim, where they learned Hebrew, raised the Israeli flag and even took Hebrew names. The Arab pioneers movement was born of romantic hope that was soon tragically dashed

By Ayelet Bechar Jul 26, 2019

When Khaled died, in 2014, at the age of 70, his family expected to bury him in a traditional Muslim ceremony in the village. For someone who lived most of his life far from the place of his birth, that could have been a symbolic return. But his children wanted him to be laid to rest next to their mother, who was born on a kibbutz in the north. “That’s what he wanted,” Khaled and Naomi’s firstborn son says. “His whole life was shaped by the kibbutz.”

How did young Khaled meet 16-year-old Naomi (their names have been changed at their children’s request) on a kibbutz in the early 1960s, when the military government ruled over Israel’s Arab citizens? Like several hundred other young Arabs, Khaled arrived on the kibbutz as part of the Pioneer Arab Youth, a movement that sounds almost like a fairy tale today. Young Arabs, mostly boys, from the country’s north were invited to live, study and work on kibbutzim. They left their village homes alone and spent years in these communities – working, eating and sleeping alongside the Jewish kibbutzniks. In some cases they made the move with their family’s blessing, but others were rebelling against their parents and their society.

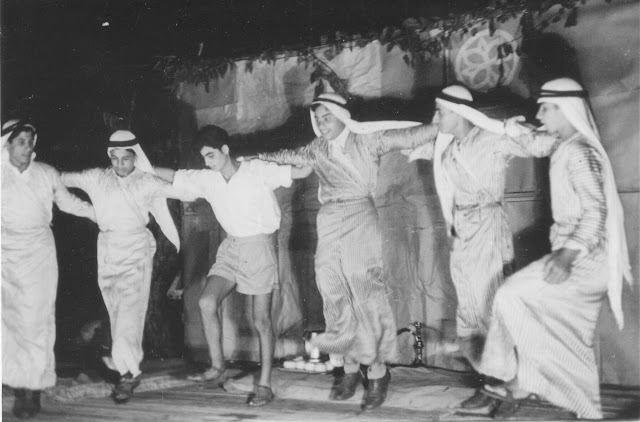

The Arab Pioneers learned Hebrew, danced the hora, raised the Israeli flag, sang “Hatikva,” the national anthem, and in some cases even took Hebrew names. Some began relationships with Jewish girls and aspired to assimilate into the kibbutz society. Others wanted to learn new agricultural methods with the aim of returning home and improving life in their villages. A few of them tried to realize a dream and establish an Arab kibbutz.

“The Jews we had met until then were part of the cruel suppression by the military government,” Mahmoud Younes recalls in a conversation at his elegant home in the town of Arara in the Triangle’s Wadi Ara area. Sitting next to an expressive painting of a dove of peace, he continues, “Suddenly we were sitting with Jews as equals. Eating with them in the [communal] dining room, working. A different Israel.”

The movement, which was an initiative of the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair youth movement, existed from 1951 until 1966, the same year that military rule over the country’s Arabs ended. At its height, around 1960, it had 1,800 members and 45 branches in Arab villages. The participants had a uniform – the standard dark blue Hashomer Hatzair shirt with a white string, along with a kaffiyeh and aqal (headband). They also had their own emblem, in the form of a proud youth movement member standing under an Arab-style arch, and they had a variation of the movement’s slogan: “hazak vene’eman” – be strong and loyal – instead of “hazak ve’amatz” – be strong and brave. The Arab movement members took part in hikes, in May Day parades, even in Independence Day folk dancing

Ahmad Masrawa at the chicken coop at Yakum.

This extraordinary idea, which has all but been erased from history, was conceived even before 1948 by two Hashomer Hatzair members who took literally the slogan “Zionism, socialism and the brotherhood of nations” and thought it could be realized by inviting Arabs to the kibbutzim. They were the youth leader Avraham Ben Tzur – who arrived in Palestine on his own from Germany at age 14, grew up on kibbutzim and taught himself Arabic – and Aharon (Aharonchik) Cohen, a Middle East scholar whose views placed him on the movement’s extreme left politically.

Even after the 1948 war, they didn’t abandon the idea. In 1950, Younes, an energetic 19-year-old from Arara, arrived at Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim wearing khaki pants whose cuffs were stuffed into his socks. The kibbutz was leery of letting him in, especially for security reasons, but Ben Tzur and Cohen persuaded the members, arguing, “We educated people for coexistence and the brotherhood of nations, and now when the test comes we say no? That would be fraudulent.”

The kibbutz agreed to ignore the military government’s restrictions, which included a ban on Arabs leaving their villages without a permit, and to accept young people for a trial period of training. The first six arrived in November 1951, and after a while, the group numbered 15, including two girls.

An article in the weekly Haolam Hazeh from March 1952, titled “Revolutionary Experiment,” has a photograph of the young Arabs wearing typical Israeli kova tembel bucket caps. “It was an encounter of two alien worlds,” the article observed. “Quite a few kibbutz people had expected a gang of foul savages, while the Arab lads were anxious about their meeting with the Yahud” – Arabic for “Jew.” The report adds that the sons of the fellahin learned “efficient methods of agriculture and worked with tractors and combines, in the groves and in the apiary.”

Hashomer Hatzair decided to formalize the movement. A 14-point platform was adopted at an inaugural celebration in Acre in 1954. Greetings were delivered by Ya’akov Hazan, a leader of Mapam, the political party that had sprung from Hashomer Hatzair, and by the renowned poet Avraham Shlonsky. A special poster was designed on which the Arab pioneer brandished two flags: the red flag of socialism but also the blue-and-white banner of Israel. A choir from the movement’s branch in the village of Kafr Yasif sang the Hebrew “Song of the Harvest,” and young Arabs from the village of Jedida performed Jewish and Arab folk dances along with Jewish representatives of Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk.

Latif Dori, who immigrated from Iraq in 1951 and established the Hashomer Hatzair branch in the Hiriyeh ma’abara – a transit camp for new immigrants – outside Tel Aviv, delivered greetings on behalf of the youth in the ma’abarot. One of the few Jews in the movement who spoke fluent Arabic, he followed the activity of the Arab youth closely for years. “It was a new world for the young Arabs,” Dori said in a 2008 interview in the offices of the left-wing party Meretz, which later became his political home. “From the flimsy house, or house of mud, from the tent, to come to a kibbutz, to all of its luxury, even in the ‘50s – it was like day and night. The youngsters understood that the kibbutz was doing something great for them, opening new horizons, giving them professional training, and all of it for free.”

The movement was launched with great aspirations, but from the outset its founders had no clear answer to the question of how the Arabs could achieve hagshama – the “fulfillment” that was supposed to constitute the realization of the ideological and practical training they had received. Were they supposed to return to develop their native villages, establish Arab kibbutzim or become members of existing kibbutzim? It was a period in which Hashomer Hatzair, the spearhead of Zionist land settlement, continued to establish kibbutzim and expand them on the ruins of Palestinian villages and on their expropriated land.

Time to get married

Ahmad Masrawa, Gal Rumbak

The sweeping story of Pioneer Arab Youth is rife with contradictions that resonate with a painfully contemporary chord. The chronicle that follows is based on interviews conducted over the past decade. Many of those involved are no longer alive, others are too aged to tell a coherent tale. Even so, a reunion of a few veterans was held recently on the occasion of the screening of a short documentary by David Ofek and myself. The film, “I Used to Be Zvi,” tells the story of Ahmad Masrawa from Arara, who at age 14 was invited to become part of the “youth society” of Kibbutz Yakum south of Netanya. The film will be screened in September at the country’s cinematheques as part of a project, “The Voice of Ahmad,” commissioned by the Sam Spiegel Film and Television School.“

This story has to be understood in terms of the atmosphere of that period – it’s hard to take in today,” Masrawa said. “There was chaos in the villages.” Israel’s expropriation of farmland produced hunger among the fellahin, and the military government prevented them from looking for work outside their villages. His parents received an offer they couldn’t refuse: “From the conservative, religious, village world, I was invited into the hidden world. The only Jews I knew at the time were the military governor and the police officer. But I realized that it couldn’t get any worse.” Masrawa said goodbye to his parents and boarded the bus to Yakum. On the kibbutz, he and his friends were given new names: Zvi, Yitzhak, Amos, Natan

Avraham Ben Tzur.

In contrast to Masrawa’s experience, in many cases the Arab parents objected vehemently to their children leaving. “The parents and the elderly saw it as a sign of compromise with an occupying enemy,” Haolam Hazeh wrote in 1952. The Jewish leaders of the group were also aware of that conflict. Abraham Ben Tzur, who died in 2013, was 85 when I interviewed him, confined to his room on Kibbutz Lehavot Bashan. His memory was on the decline, too, but his archive was in exemplary order, including yellowing newspaper clippings, files of correspondence, and, the jewel in the crown, a meticulous diary he kept that chronicled the life of the first group

Working the land together. The movement reached its height around 1960. From the private archive of Ahmad Masrawa

With the aid of large glasses, Ben Tzur read from his diary about the first member of the new group, Mahmoud Younes, who unlike the others came from a well-to-do, landowning family: “April 5, 1952. Yesterday Mahmoud returned from a visit to his village. His whole family urged him to leave the kibbutz and come back to the village. ‘After all, you own land. And why should you do manual labor? It’s time you got married and managed your farmstead.’”

Atallah Mansour. Gil Eliahu

The uncharted path was studded with misunderstandings, some of them amusing. “Today a new fellow came to us, from Gush Halav [Jish], named Atallah,” Ben Tzur read from the diary. “At first he made a very bad impression on me. Three things in particular: 1. Doesn’t look you in the eye; 2. Pest.” Even decades later, Ben Tzur declined to read out the third problem, because “the chap could still take offense.” Atallah Mansour, a Catholic of 85 who lives alone in his Nazareth home, has an explanation for the bad impression he made. His main purpose in coming to the kibbutz was to learn Hebrew. To that end, he says, he pestered kibbutz members at every opportunity, asking what words meant. Of Ben Tzur he says, “He was shy, but he wanted very much to be able to speak Arabic and made a supreme effort to pronounce the letters properly. We would laugh and tease him about it.”

Mansour’s village didn’t have a high school. When he was 14 he went to Lebanon for schooling but had to return after the 1948 war to avoid becoming a refugee. “I told myself, if I’m already in this mess, I might as well go with the flow,” he said with a smile. “I had my eyes open already then. I thought this was an ideal way of life of equality and cooperation.” Having been invited to be part of the first group of Arab trainees at Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakin, southeast of Haifa, he quit his job – he extracted nails from planks used in construction – only to end up assigned to a construction unit on the kibbutz. “There’s a chicken coop on that kibbutz that I built,” he notes. “At the end of every workday I would go to the reading room and practice Hebrew. My feeling was that learning the language would make things easier for me down the road.”

Mansour was right. He became the first Arab journalist who wrote in Hebrew, first for Haolam Hazeh and later, for four decades, for Haaretz. The shelves in his study are bursting with books and periodicals, most of them in Hebrew. He himself is the author of a few of the books, including his 1966 work “In a New Light,” the first novel written by an Arab in Israel in Hebrew. It’s about a young Arab who falls in love with a kibbutz girl and is allowed to remain on the kibbutz only at the price of posing as a Jew

Members of the Pioneer Arab Youth movement, 1956. The organization ‘implanted all kinds of hopes about fraternity, peace and friendship,’ the son of one veteran says. Hashomer Hatzair Archive

Mansour relates how he and his friends learned to dance the hora (“Jewish girls were brought from the educational institution, and they taught us”), and how the young Arabs taught the Jews the debka. They enjoyed the kibbutz’s relative abundance but had to get used to porridge at breakfast, not to mention the gefilte fish and similar peculiarities. “One time a nail went into my foot,” Mansour recalls. “I was taken to the clinic and told that I had to eat well, so they gave me salted fish every day. I took one taste and almost passed out – I couldn’t stand the smell.”

The workweek was 45 hours. In the evenings, after work, they learned Hebrew and studied Zionism and socialism (“What’s the difference between a [Soviet] collective farm and a kibbutz? The kibbutz is a dream, the collective farm is hell”). There was also a short course on electricity. A young man from Arara gave a talk on the life of Pushkin, a young woman from Nazareth wrote an article about the problems women faced in Arab villages. Mansour edited the group’s bulletin, “Ray of Light.” The movement also founded an Arabic-language publishing house, which put out some 200 titles.“

One day, the military police showed up at the kibbutz and asked whether there were any Arabs there,” Masrawa recalls. “I hid on the hill, between my group’s cabins.” The kibbutz members stood up to the military police, stopped them from entering and refused to turn over the young Arabs. Shaul Yoffe, who had been a commander in the pre-state Palmach commandos and was one of the founders of the kibbutz, chased away the officers. Masrawa felt not only relief but also a sense of true belonging. The newspapers wrote about how courageously the members of Kibbutz Yakum protected their wards, who technically were on the kibbutzim illegally, having left their villages without a permit.

Following his years in Yakum, Masrawa was a construction worker in Tel Aviv, studied German in Germany and became the owner of a stationery store back in Arara. He married at 40, has four children and is now a grandfather. After the 1967 Six-Day War, he joined Matzpen, a radical Jewish-Arab socialist group, and was active in Jewish left-wing circles. His story intertwines with the political and bohemian elite of the period (“On Fridays we would meet at Café Kassit” in Tel Aviv, a hangout for intellectuals during Israel’s first decades). Today he remains a social and political activist.

Their “pioneering” period led many of the Arab participants into political involvement upon their return home. The vast majority of them joined Mapam and helped the party recruit voters among Israel’s Arab citizens. The movement produced leaders of local governments and even two Knesset members. Mustafa (a pseudonym), was a member of the first group of Pioneering Arab Youth, and was very friendly with Golda Meir in her final years. His son Nayif, 54, recalls how “I visited her in the hospital with my mother, and we exchanged gifts,” he said. When a baby girl was born in the family, Meir sent a gold chain for her, and the father, deeply moved, named the girl after the Jewish politician. “It was weird,” says Nayif. “The children would insult her, taunt her. ‘Hey, are you a Jew? Why did they give you a name like that?’ We in the family would also deliberately flood her with housework and say to her jokingly, ‘Golda, come here, Golda do this.’ Until she put an end to it: She called everyone to a family meeting and announced that she had chosen a new – Muslim – name for herself.

Rushdi Massarwi and his daughter, Kifah. Rami Shllush

Room for all

Some of the former Arab Pioneers look back on it with a nostalgia that they have passed on to the next generation. One person invited to a screening of the film last spring was 78-year-old Rushdi Massarwi, who said he was “so happy to see the old comrades again.” He remains grateful to the kibbutz movement for freeing him from a life under the military government and giving him the means to support himself amid the limited educational and employment opportunities in the village, most of whose land had been seized by Israel.

“My father was part of that movement by choice, not constraint,” says Rushdi’s daughter, Kifah. “He believed in that path and also imbued it in us children from age zero. Grandma Nehama from [Kibbutz] Gan Shmuel, Grandma Merika from Kibbutz Dalia, Grandma Etka from Lehavot Habashan – they were all like family members for me. They brought quality toys that you didn’t see in the Arab village back then, and during summer vacations they hosted me on the kibbutz, where I learned Hebrew.”

The ways of communal living also trickled into the family’s home in Baka al-Garbiyeh. The chores were divided following a family assembly and an open discussion. As an adult, Kifah had a diverse career as a manager in the Na’amat women’s organization, in her town’s local government and as a board director in a government corporation. She says it all began on the kibbutz. “I understood, unconsciously, that the Jew is not an enemy. I absorbed an education [that allowed me] to understand and get to know the other side. That determined the course of my life.”

Nayif, too, grew up with the kibbutz ethos. His father, Mustafa, was nostalgic for the kibbutz to his last day. “He would bring up his happy, joyful memories. I saw his excitement at having worked in the barn, or on the harvest. Sometimes he would borrow or even steal a few liras to travel to the kibbutz. And people from the kibbutz came to his funeral.

Jews and Arab youths dancing the debka on Kibbutz Yakum near Netanya, 1955. Hashomer Hatzair Archive / Yad Yaari Research & Documentation Center

Mahmoud Younes, too, always cast a romantic aura over his period on the kibbutz. After an Arab-Jewish outing to Lake Kinneret in 1952 that included folk dancing, he wrote about the experience in a Hashomer Hatzair journal: “We raised the flag very slowly … and among the hills of Mishmar Ha’emek the salutation of the Shomrim was heard powerfully: ‘Hazak Ve’amatz!’ [‘Be strong and brave!’]That salutation mingled in my blood and my heart and filled me with pioneering strength.” He concluded by saying that he would soon return home to raise the banner of socialism, “a very difficult task in the backward feudal village under the rule of the military government …. We are returning to shout out in our villages that there is a different Israel, a democratic Israel, an Israel of peace, there is a different Jewish people … which is keen to connect with us in the struggle for the independence of both peoples.”

In 2008, when Hashomer Hatzair turned 95, Younes attended “Once a Shomer, Always a Shomer” – a huge reunion at Givat Haviva, the kibbutz movement’s education center, which operates programs intended to promote Arab-Jewish shared society. For his part, Younes was still imbued with the same spirit. With a light step, his hair white but abundant, he wandered about, his heart pounding, at the meeting with the comrades. He asked the young people in the blue shirts which branch of the youth movement they were from

Mahmoud Younes.

“I feel part of this,” he said. “To this day, when I get into an argument in the village, people call me the Yaari of the Arabs” – referring to the Hashomer Hatzair ideological leader Meir Yaari (1897-1987). “I believed the Mapam institutions when they talked about the Arabs’ right to self-determination, and I believed, and believe to this day, that there is a place for both peoples in the joint homeland.” One person he met at the gathering recalled affably that “they were nice, but made trouble. What trouble? ‘Security’ trouble, because the military government persecuted them. Something remains of the education they received from us. Too bad [the project] didn’t continue, but what can you do?”

For Ben Tzur, the passage of time hardly shook his faith in the idea. “From the outset the idea wasn’t for the Arabs to fulfill the [terms of the] standard ideological education of Hashomer Hatzair. The intention was not to turn them into Jews, but into pioneers,” he said. Ben Tzur noted that he had taught his wards about the fate of the Jewish people and their need for a state, and at the time saw no contradiction between the national aspirations of the Jews and the Arabs. “The intention was to educate for positive Arab nationalism, not aggressive nationalism that would turn against Zionism, but one espousing historical and literary values,” he said. “I believed that things could be resolved in the spirit of the brotherhood of nations. Today I’m not so sure of that.”

When peace comes

In 1960, the Pioneer Arab Youth movement was at its peak. Its members worked, studied and joined demonstrations and petitions against the military government. But precisely then the cracks started to widen. The Jewish initiators of the idea recognized that the movement was run from above and was not independent. They also realized that the majority only took part in the work camps, where they earned a pittance. Unlike the urban Jews, who gleaned ideological affiliation from their work, many of the young Arabs were drawn to the kibbutzim by that salary, which, small as it was, saved their family from hunger

Walid Sadik. Arieh Gal

“Unlike the backward, underdeveloped village, where there was no electricity and no roads, there [on the kibbutzim] everything was spick-and-span,” recalled Walid Sadik of Taibeh, who became a Meretz legislator during the ‘80s and ‘90s. “The girls wore blue shorts, and that was already a reason to aspire to become a kibbutz member.” Sadik arrived at Kibbutz Gan Shmuel as part of a group during breaks from his studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. At first the kibbutz proved very alluring. Sadik, who died four years ago, was an elegant, dignified person with the manners of a gentleman. In conversations a decade ago, he said: “The first time in the dining room, I expected a waiter to come and serve me, until someone noticed my mistake and explained that it was self-service.”

He was offended when kibbutz members didn’t greet him when they passed him and when they didn’t invite him to their homes. “Because I didn’t know their customs, I took it to heart. I felt that they saw me as an outside worker whom they could ignore.” According to Sadik, even the “outside children” – such as the future Meretz MK Ran Cohen – had a higher status than he did in Gan Shmuel. “I worked in the yard and in cleaning, while they lived in nicer houses and worked in better jobs like farming and picking flowers, which I very much wanted to work in.”

Cohen, who came to Israel alone from Iraq when he was 10, was dubbed “little Sa’eed” (meant, insultingly, to imply that he resembled an Arab) during his time in Gan Shmuel. He explains the difference by pointing out that the Arabs arrived at the kibbutz within the framework of work camps, whereas after a few years the outside children, who actually lived on the kibbutz, were granted conditions equal to those born there. Cohen and Sadik were both part of the governing coalition formed by Yitzhak Rabin, as two of Meretz’s 12 Knesset members in 1992.

Ahmad Masrawa also noticed that differences of social class existed in the kibbutz’s model society. The Arab youths worked five hours a day and studied for three hours, while the Jewish “outside children” had the opposite schedule. “I had the chutzpah to ask why, and I was told that the Jews were subsidized by Youth Aliyah. Already then it was hard for me to believe that Hakibbutz Ha’artzi [the kibbutz movement] would collapse from supporting a group of 15 youths.”

On the other hand, when it came to clothing, distributive justice was imposed. Masarawa: “I had two pairs of pants and two shirts, and I still remember my laundry number – 264. One day I went to visit my brother, who was working in construction on Bialik Street in Tel Aviv. I saw a beautiful shirt in a show window and he bought it for me. When I got back to the kibbutz and sent it to the laundry, it didn’t come back. It was nationalized.

Arab pioneers on Hashomer Hatzair’s four-day march in 1964. Hashomer Hatzair Archive / Yad Yaari Research & Documentation Center

Masarawa was assigned to field work and was delighted to sow and reap. He was well aware that this option was all but nonexistent in his village: “Before the war, Arara’s land stretched to Mount Carmel; we had 36,000 dunams [9,000 acres]. After the war, the village was left with maybe 1,500 dunams.” When he wanted to be alone, he walked among abandoned Arab homes near the kibbutz. When he asked where the kibbutz’s neighbors were, he was told that they had “left,” but wasn’t persuaded. “At roll call, I went on singing ‘Hatikva’ with everyone, but questions started to come up that had no answer.”

It was quickly apparent that complete “fullfillment” in the spirit of Hashomer Hatzair – which would have meant the establishment of an Arab kibbutz – was an impossibility. In 1958, the indefatigable Mahmoud Younes asked Agriculture Minister Kadish Luz to set aside land for the movement to build a cooperative community. The minister referred him to the Jewish Agency, where he was told that the “national lands” were earmarked for the Jews. A few years later, Masrawa also tried to obtain agreement for establishing an Arab kibbutz in his native village. He received an unequivocal reply from the Israel Land Authority, which he still remembers by heart: “Ahmad, don’t be naive. On the expropriated land of your village we will establish three Jewish communities, which will take up arms when needed.”

Some of the movement’s members managed to apply in their villages what they learned on the kibbutz. In 1956, a cooperative vegetable garden called “The Pioneer” was founded in Kafr Yasif. In Taibeh, an agricultural cooperative called “The Hope” was established and included a plan – never realized – to set up a cooperative movie theater. The most successful cooperative was a water-drilling project that Younes established in Arara in 1957. But the dearth of land, funding and support from the establishment, along with the lack of participation by Arab society, doomed most of the cooperatives.

Atallah Mansour, too, grasped that “the kibbutz is a solution for Jews only. Anyone who isn’t a Jew but just a human being who wants to live and work, has no place there.” The injustice that was inflicted on the Christian Arab villages of Ikrit and Biram in the northern Galilee – which the Israeli army evacuated in 1948 with the (unfulfilled) promise that the inhabitants would return quickly, and part of whose land was taken over by Kibbutz Baram and Kibbutz Sasa – added to the uneasy feeling of Hashomer Hatzair duplicity.“

We were still under military rule, under supervision and suppression, our mouths shut and our feelings bottled up, and we ignored all of that consciously so that we could enjoy the pleasures of the kibbutzim,” Walid Sadik said. “We were interested in a salary, because there was no money in the village then. The payment we received for our work was good and more important at the time than those embarrassing questions.”

In return for the possibility of working under the auspices of the kibbutzim, without a permit from the military government, the Arab guests tried to keep quiet. “Gan Shmuel is built partly on lands of the village of Sarkas, and the people of Gan Shmuel themselves expelled the Palestinian inhabitants during the war. I know personally, by their names, the people who carried out the expulsion,” Sadik said. “When we occasionally raised the issue that the kibbutzim, which declared that they were against land expropriations, were in fact settling those same expropriated lands, we were told: ‘When peace comes we will get along. After all, to this day not one refugee has shown up to demand his land.’ We didn’t have a Palestinian consciousness such as exists today, we talked about the ‘stolen land,’ not about Palestine.”

Sadik summed up the kibbutz chapter of his life by saying that “the coexistence was forced, not genuine. Coexistence is expressed in everyday life, in deeds, not in theories. It was hypocrisy per se, and I think that the same hypocrisy exists to this day. The kibbutzim believe above all that this is a Jewish state and that the Jews in it are more privileged than the Arabs and have priority in everything. This, in my opinion, is the spirit that resides in every Jewish Zionist, and especially among the kibbutzniks, the most Zionist settlers there are.”

Mansour offered the following image to describe the dynamics between Hashomer Hatzair and the native-born Arabs: “They came to us, to our house, and said: We want half the house. After that they said, fine, you can stay. If you help us wash the dishes, maybe we’ll give you a room. But if I stay in my own house, I want to sit in the living room, not to live in the yard or in the hallway, where the shoes are kept. We were equal in principle, but we weren’t treated as equals for even one day.

Mahmoud Younes, second from right. In the center is Ya’akov Hazan, a founder of Hashomer Hatzair youth movement and the Mapam party. 1956. Hashomer Hatzair Archive

Worm in the fruit

But the most difficult test for the movement lay at the personal level, in the love stories between young men from the Arab villages and young Jewish women from the kibbutzim. The project produced a few mixed couples. Khaled and Naomi left the kibbutz for the city. Mohammed Jasser Haj Yehiyeh and Yehudit, from Kibbutz Merhavia, also decided to leave and settle in the Arab town of Taibeh, where they raised four children. After Mohammed’s death a few years ago, both Yehudit and the children left Taibeh.

The most highly charged and best-known struggle waged by a mixed couple was that of Tzvia Ben Matityahu from Kibbutz Givat Hashlosha and Rashid Jaffer Masarawa from Baka el-Garbiyeh, who is now 78. He joined a work camp of Pioneer Arab Youth on Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk while he was still in fifth grade. “That was the start of my love affair with the kibbutz,” he said. In the summer before seventh grade, all his classmates followed suit. A year later, he left home, against his parents’ vigorous objections. “My father told me, ‘They eat pork on the kibbutz.’ In the end, he agreed, on condition I wouldn’t do bad things.”

Rashid was originally accommodated at Kibbutz Dalia, before moving to Givat Hashlosha, where he met Tzvia, who was in 11th grade.

“We were both athletes,” he recalled. “We fell in love. The young Jewish members of the kibbutz encouraged me, and the older ones were ashamed to tell me: ‘Don’t go with her, because you are an Arab.’ Later, when they came and told me it was no good, it was too late.” Tzvia couldn’t believe that the kibbutz she loved so much wouldn’t accept the love affair, but Rashid understood the problem immediately. He chokes up when he talks about what happened

Tzvia Ben Matityahu, Rashid Jaffer Masarawa and their child. The headline reads ‘Is the kibbutz racist?’

After being married in Cyprus, the young couple had to leave the kibbutz. They moved to Hadera and gave their firstborn son a double name: Ronen in Hebrew and Riad in Arabic. They suffered from the treatment of their neighbors in the Jewish city, and decided to try their luck in Gan Shmuel, a kibbutz of the Hashomer Hatzair movement.

“We were told that there was no racism there and that we would certainly be accepted. It was Ran Cohen who persuaded us. We had already been shown our room and the children’s house for the baby, but at the kibbutz assembly, just before the vote, someone mentioned that I was from Sarkas. He knew that my parents were from the demolished [Palestinian] village, and argued that if I was accepted as a member, it would mean that I was being returned to my village.” At this stage of his story, Rashad broke down and wept, still deeply affronted by the kibbutz’s majority decision not to grant him membership, following stormy meetings and revotes.

“It was a tremendous drama, possessing ideological dimensions,” Ran Cohen recalls. “The agonizing was real. The opponents said: ‘The kibbutz is a Zionist body that is situated on Jewish National Fund land, so why would we ever want to settle Arabs on it?’ There was also a social aspect. After all, the kibbutz is a Jewish entity with Jewish holidays, customs and culture. How would an Arab fit in? I argued that this was a humane issue, a matter of human dignity, and that both Rashad and Tzvia and their baby deserved a place in this land. In the end, I saw that it was going to cause a rift that would shatter the kibbutz. Some members wanted to leave over the issue, and I had to stop them.”

The juicy story was covered extensively in Haolam Hazeh in 1964 under the headline “Is the kibbutz racist?” Of Gan Shmuel, the weekly wrote, “It suddenly emerged that those fears of the Jewish ghetto cropped up in the heart of what is considered the glory of the new Hebrew nation: in the heart of the members of the deeply rooted, strong kibbutz.”

Tzvia likened her story to that of kibbutz girls who had fallen in love with an Iraqi or Moroccan Jew. Her world collapsed, she told the magazine, when she grasped that “it was prohibited for someone to join the kibbutz – not because he’s unsuitable, not because he’s an idler, not because he’s maimed or uneducated, but because he was born an Arab! Even the kibbutz, this beautiful fruit, is being eaten away by the worm of racism.” Subsequently, the couple was granted membership in Kibbutz Ein Dor, but Rashid didn’t adjust to life there. They lived with their three children in Hadera and later in Tel Aviv and Netanya. Their firstborn son served as an officer in the Israeli army.

The participants in the Pioneer Arab Youth movement viewed the fate of Rashad and Tzvia as final proof that self-realization wasn’t in the cards. Not only would the state not allocate even a clod of soil to the Arab community, but no Pioneer Youth would be accepted as members of a Jewish kibbutz. In the meantime, the ending of the military government in 1966 created possibilities for study and employment for the suddenly mobile young Arabs. Thousands flocked to the cities to work in construction. According to Ben Tzur, the end was also hastened by the volunteers from abroad who streamed into the kibbutzim after the Six-Day War. “Culturally, they were far more suited to kibbutz life, so there was no longer a need for Arab working hands.”

In parallel, with the rise of Nasserism and the recognition of the war’s consequences, young Arabs began to give expression to their Palestinian nationalism. At a gathering in the summer of 1967, members of the Pioneer Arab Youth stunned their Jewish comrades by their vehement objection to the “Jordanian option” – that is, Jordan being declared the lone Palestinian state – which Mapam was urging as a solution to the conflict. As Ben Tzur put it, “Suddenly I felt that everything had changed, had taken a nationalistic direction. They talked about having to fight and establish a state for themselves. That surprised me very much; I understood that this was the end.”

According to Ahmad Masarawa, “an argument started over a Palestinian state, the return of the refugees. I said, ‘Explain to me how Zionism and socialism go together.’ Looking back on it today, I say they threw sand in our eyes. They made a mockery of the ideal. They played with lofty ideas, but in practice they behaved otherwise. What did they actually want from us?”

Khaled and Naomi’s son, who chose to live as a Jew, said his father was tormented all his life by questions of identity. “When I decided to enlist for mandatory army service, my father really got on my case, but in the end he walked around proud that I was wearing red [paratroopers’] boots.” His father, he said, was able to take advantage of the opportunities the kibbutz gave him, but the son qualified that remark painfully: “The idea was amazing, but the racism won out. To bring those young people to the promised land and then to tell them, you can’t, because you’re Arabs …. Hashomer Hatzair should have thought about the end of this story before they wrenched these young people from their villages and implanted all kinds of hopes in them about fraternity, peace and friendship. They, the Jews, thought that they, the enlightened ones, could educate them and make them decent people, but in the end they shattered their dreams and turned them into menial laborers. ‘The kushi [a derogatory Hebrew term for a dark-skinned person] has done his duty, the kushi can go’ – back off, kushi. It’s sad that I don’t have anything warmer or better to say about the subject.”

“A fluttering of two souls” is the description offered by the historian Shaul Paz for the split personality of the Hebrew youth movements regarding the Arabs. The cause, he says, was the clash between the Zionist need for pioneering land settlement on the one hand, and justice and the brotherhood of nations on the other. In the few pages that he devotes to Pioneering Arab Youth in his 2017 Hebrew-language book “Our Faces Toward the Rising Sun: Members of the Pioneering Youth Movements in Israel: The Second Generation, 1947-1967,” Paz maintains that the movement was above all a means to ease the moral divide among the Jewish young people, and get them to rally around a lofty idea.

According to Paz, who is originally from Kibbutz Mizra, the leaders of Hashomer Hatzair “wanted to believe that, just as a new Jew was being created, so, too, a new Arab would be created, one who could be a socialist, a pioneer and a kibbutznik as well. Even the biggest dreamers such as Abraham Ben Tzur and Aharon Cohen knew from the first moment that the Arabs wouldn’t be allowed to establish a kibbutz, but of course they didn’t tell them that. It was convenient for them to create this illusion because, after all, they were all about the brotherhood of nations, equality, solidarity, socialism and all those slogans. A pioneer youth movement needs to pose utopian challenges in order to fire up the young people and get them to cooperate. It’s a marvelous feeling, you know – who doesn’t like to give? But it was accompanied by discrimination and inequity. As with the Mizrahim [Jews who had their roots in North African and Arab countries], we knew better than them, we encouraged them and we brought them here, but we never saw them as equals.”

As Paz puts it, Pioneering Arab Youth was “a fascinating, astounding, short-lived experiment that disappeared from memory. With it disappeared our dreams, aspirations and illusions that a different Israel was possible.”

Ayelet Bechar, a documentary filmmaker and journalist, is currently working on a documentary series for TV, internet and radio about young Arab citizens of Israel, commissioned by the Kan public broadcaster’s Arabic service, Makan.

Film charts failed experiment inviting Palestinian teens to become kibbutzniks

26 September 2019

Mondoweiss – 23 September 2019

A new documentary brings to light an episode almost completely erased from Israel’s official history – and one that reveals how Israel’s apartheid character was established from its birth.

The “The Voice of Ahmad” by directors Avshalom Katz, David Ofek, Ayelet Bechar, Shadi Habib Allah, Naom Kaplan, Mamdooh Afdile, and Iddo Soskolne is being screened in Israel this month. It centers on the extraordinary early life of Ahmad Masrawa back in the 1950s, as the recently established Jewish state was finding its feet.

Masrawa was one of many hundreds of Palestinian teenagers in Israel who were adopted by a kibbutz, agricultural communes that were at the core of the Zionist movement’s efforts to Judaize lands just stolen from the Palestinian people – both from refugees forced out of Israel and from the small number of Palestinians, like Masrawa, who managed to remain inside the new state.

Today, hundreds of these kibbutzim exist, all of them exclusively Jewish and controlling the vast bulk of Israeli territory. Israel’s Palestinian citizens are effectively banned from living in them.

But, as this new film shows, there was a brief moment when a handful of progressive Israeli Jews imagined a different future in which Jewish and Arab kibbutzniks could live together. That experiment ended in complete failure.

A stab in the back

Masrawa is part of the largely-overlooked Palestinian minority in Israel – today a fifth of the country’s population. He was among a rump population of Palestinians who avoided the mass expulsions of the 1948 Nakba, or catastrophe, that created Israel on the ruins of the Palestinian homeland.

A few years later, under international pressure, Israel belatedly gave this minority a very second-class citizenship.

The fact that Palestinian citizens, now numbering 1.8 million, have the vote is often cited as proof that Israel is a normal western-style democracy. Nothing could be further from the truth, as this documentary underscores.

Ahmad’s strange teenage years have been unearthed now because he starred in a short documentary in the mid-1960s, called “I Am Ahmad,” that was initially censored and, when it was finally screened, caused uproar. Ram Loevy, its director, says in the new film that his documentary was viewed by most Israeli Jews at the time as “a stab in the back.”

Slum neighborhoods

It was the first time an Israeli film had ever allowed an “Israeli Arab” – a Palestinian citizen of Israel – to be the protagonist.

“I Am Ahmad” follows Masrawa as a near-two-decade military government imposed on Israel’s Palestinian minority is being lifted just before the outbreak of the Six-Day war. He is filmed leaving his poor village of Arara in northern Israel to travel to the rapidly expanding Jewish coastal city of Tel Aviv to find work.

Masrawa narrates the film, providing personal reflections in Hebrew on what it is like to live effectively as a foreign worker in your own country.

Like many thousands of other Palestinians in Israel, he was forced by day to work as a casual laborer on construction sites, disappearing at night to dwell in slum neighborhoods of tin shacks set up by Palestinian citizen workers on the outskirts of Tel Aviv.

High death toll

The Voice of Ahmad is compilation film, comprising six short documentaries inspired by or expanding on I Am Ahmad, a restored version of which opens the new movie.

Sky of Concrete sees an elderly Masrawa spend the day with a group of today’s casual laborers from his village on a building site. Little has changed half a century later, as Masrawa discovers, including the same tragically high death toll in an industry that barely seems to value the lives of its non-Jewish workers.

But the most fascinating segment of the Voice of Ahmad is the backstory of why Masrawa ended up in the 1960s building new homes for Jewish immigrants arriving to entrench the dispossession of Palestinians like himself. That context is not provided by I Am Ahmad.

It would have to wait another half-century for that story to be revealed in “I Used To Be Zvi,” a kind of belated prequel to “I Am Ahmad.” Its co-director, Ayelet Bechar, recently expanded on her research for the film in an article for the liberal Haaretz newspaper.

Judaizing Palestinian land

“I Used To Be Zvi” concerns the 18-year period between 1949 and 1967 before Israel seized control of the occupied territories, a time when Palestinians in Israel lived under harsh military rule despite their citizenship. They were locked up inside their few surviving communities while their new rulers confiscated almost all their farmland to settle Jewish immigrants in their place.

While this land larceny was taking place, however, two prominent Jewish socialists began a limited experiment in mixed living that appeared – at least, superficially – to challenge Zionism’s core principle.

The lands seized from Israel’s Palestinian minority were transferred to hundreds of kibbutz, socialist-style agricultural communes set up for Jews as part of Israel’s official Judaization policy.

Many decades on, these communities control almost all of Israel’s land, which they hold as nationalized territory on behalf of all Jews around the world, not Israel’s citizens.

Although the kibbutz has been widely extolled in the west as a model of egalitarian, cooperative living – and in Israel’s first decades attracted starry-eyed European and American volunteers – all of these communities use vetting committees to ensure no Palestinian citizens gain admission.

Mixing with girls

In Israel’s early years, however, a few Jewish socialists argued that the kibbutz movement should live up to its supposed ideals of “Zionism, socialism and the brotherhood of nations.” They established a Pioneer Arab Youth organization, recruiting Palestinian teenagers in Israel like Masrawa to live on a kibbutz.

The obstacles were many. Each had to harbor its Palestinian youngsters as fugitives from the authorities. The military government required them to live in their own, segregated and imprisoned communities.

And despite professed lofty ideals, most Jews in the kibbutz movement regarded their Palestinian neighbors not as potential brothers but as a threat to Israel’s ethnic state-building project.

These young Palestinian recruits, meanwhile, were not there out of a love of Zionism. They wished to break free of the stifling economic and social restrictions imposed by the military government. A few admit they were enticed too by the chance to mix with kibbutz girls.

Kibbutz ambassadors

Masrawa arrived at his kibbutz, aged 14, under a new Hebrew identity he had been assigned: “Zvi”. But differences of treatment were apparent from the outset.

Palestinian members were required to wear a different uniform and allocated menial tasks. Even Pioneer Youth’s motto prioritized subservience, amending the kibbutz slogan “strong and brave” to “strong and loyal.”

And while the kibbutzim were grudgingly allowing handfuls of Palestinian teens into their midst, they also colluded with the military government to steal the remaining farmlands of the villages from which their Palestinian wards hailed.

There was a subtext of political missionary work too. Avraham Ben Tzur, a Pioneer Youth founder, observed that the aim was to turn impressionable Palestinian youth into ambassadors for the kibbutzim, presumably in the hope that when they returned to their villages they would try to justify to their extended families the theft of the villages’ lands by the kibbutzim.

The project quickly started unraveling when it became clear that Pioneer Youth’s organizers had no vision beyond a parochial, Jewish one.

Feelings bottled up

A heartbreaking, reconstructed scene in “I Used To Be Zvi” shows young Masrawa, filled with the kibbutz ideals of shared, egalitarian living, heading to the offices of the Israel Lands Authority to inquire about setting up the first Arab kibbutz next to his village of Arara, south of Nazareth.

The senior official burdens him with a long list of conditions he must meet before he can be given approval. When Masrawa fulfills his side of the bargain, he is given yet more demands, and more, until finally the exasperated official explains the facts of life to Masrawa.

He tells him the government will never allow an Arab kibbutz. Not only that, he adds: “On the expropriated land of your village we will establish three Jewish communities, which will take up arms when needed.”

The clear implication is that these Jewish communities will, if needs be, use their weapons against Masrawa and his fellow villagers to enforce the theft of Arara’s lands.

Indeed no Palestinian kibbutz, or even a genuinely mixed one, was ever permitted.

Walid Sadik, who later served as a Palestinian member of the Israeli parliament, observed that he and the other Palestinian kibbutzniks had “kept our mouths shut and our feelings bottled up.”

Intermarriage rejected

But it was the experience of another Palestinian, Rashid Masarawa, that sounded the death knell of Pioneer Youth.

In the mid-1960s he fell in love with and married a Jewish woman, Tzvia Ben Matityahu, on Kibbutz Hashlosha. Given Israel’s restrictions on mixed marriages, which continue to this day, the couple had to travel abroad to wed.

On their return, they were exiled from Hashlosha, and sought refuge among friends at another kibbutz, Gan Shmuel.

Their application to live there was rejected too, however. The vast majority of members objected because the Masarawa family originated from Sarkas, a village destroyed by Israel in 1948 to prevent its refugees from ever returning. Gan Shmuel had been built on Sarkas’s stolen lands to appropriate them.

Masarawa tearfully noted: “If I was accepted as a member, it would mean that I was being returned to my village.” In the Zionist worldview, the danger was that the kibbutz members were being asked to concede something that might set a precedent for a right of return.

‘Sand thrown in our eyes’

The Zionism of these Jewish socialists decisively trumped any semblance of shared humanity or compassion. The Pioneer Youth dissolved soon afterward as young Palestinians in Israel shifted allegiance towards the new Arab nationalism of Nasserist Egypt.

Ben Tzur, founder of Pioneer Youth, recorded his shock to Bechar that, after Israel occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza in 1967, his Palestinian recruits voted down a plan much favored by kibbutz members to create an alternative state for Palestinians outside their homeland, in Jordan.

Masrawa observed: “Looking back now, I say they threw sand in our eyes. They made a mockery of the [kibbutz] ideal.”

No hope of brotherhood

The military government may be a distant memory now but its legacy persists.

Israel’s Jewish character still precludes equality for Palestinians, even those with citizenship. Assumptions among Israeli Jews of disloyalty from Palestinians are still commonplace. Palestinian land is still being Judaized, though now that Palestinian citizens have lost all but a tiny fraction of their lands, that process is chiefly taking place in the occupied territories. Rigid ethnic segregation ensures mixed marriages are still rare and deplored.

Palestinian voting is still no more than window-dressing, and now increasingly characterized by Israeli politicians like Benjamin Netanyahu as fraud. He declared only this month that Palestinian citizens had tried to “steal the election” by exercising their democratic right.

And brotherhood, of course, is today not even an aspiration.

Ugly ethnic supremacism

The “Voice of Ahmad” ends with a short film, The Helsinki Accord, by two Israeli citizens – one Jewish, the other Palestinian – who have sought a self-imposed exile in Finland. There they live as neighbors, share a passion for sweating it out together in a sauna, and jest about Israel’s destruction by a nuclear bomb.

The Jewish friend, Iddo Soskolne, whose family originates from Poland, says Finns have nicknamed him “felafel” for being from the Middle East.

Finally, the pair concede, they have found equality in their status as a minority, as outsiders, in Finland. They have found a true brotherhood that would be impossible in Israel.

It was, after all, the good guys – the socialists – who established Israel’s version of apartheid alongside and enforced by the “egalitarian” kibbutz. These racist political structures were created by an Israeli Labour party whose political demise is now – after a decade of rule by the ultra-nationalist right – much lamented abroad.

But the reality is that the Zionism of Israel’s founders was as ugly a project of ethnic supremacy as the Zionism of today’s nationalist right led by Netanyahu. Ahmad Masrawa’s story is a helpful reminder of that truth.