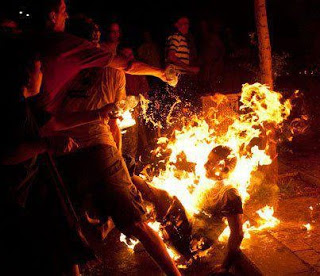

Protest for social justice, Tel Aviv, Israel

Israel is not only the most represssive state that claims to be a western democracy, it is one of the world’s most unequal societies. It is the poor Israeli Jews who effectively pay for the Occupation of the West Bank and the military expenditure. In turn they are fed the nationalist rhetoric and xenophobia of Zionism.

As the social protests look likely to be rekindled in Israel this summer and a man sets himself alight in a horrific incident captured in what is a distressing video, the settlers are given carte blanche to attach Palestinian inhabitants.

They key question for Israel’s social protestors is whether they are politically capable of going beyond last year, when the Israeli Labour Party helped ensure that the protests weren’t ‘political’ i.e. didn’t raise uncomfortable issues such as the Arabs of Israel, the settlements etc.

Below is a very useful report by the Association of Civil Rights in Israel

Tony Greenstein

see also Social Justice Activist Sets Himself on Fire During Protest in Israel (GRAPHIC)

Published on Jul 14, 2012 by yisraelpnm, 14.7.2012

52 years old Moshe Silman set himself on fire following a protest for social justice

How Israeli Governments Drained Social Services – New ACRI Report

Written and edited by: Atty. Tali Nir

Research and writing assistance: Tamara Traubmann, Atty. Ronit Gilad, Ido Katry

English translation: Gila Svirsky

English version edited by: Yoana Gonen

Cover design and infographics: Noa Olchovski | dropouts.me

Cover photo: Oren Ziv, Activestills

Thanks to ACRI staff members, who provided information and helpful comments; to the experts who reviewed the report; to the former civil service employees who were interviewed for this report and shared their experience with us; and to all of ACRI’s members, volunteers, and supporters – whose commitment and generosity enables our work.

Note: The following is an English summary of the comprehensive Hebrew report.

INTRODUCTION

The social protest in the summer of 2011 transformed the public agenda in Israel and shined light on an important truth that had long been suppressed: Israel had become a country in which many people could no longer realize their basic right to a life with dignity and a decent standard of living. In tent cities throughout the country, thousands spoke of how hard it is to make a living, to make ends meet, to afford housing, and voiced their concerns about the poor education their children are getting. These stories were repeated throughout Israel by people from diverse groups and occupations, revealing a deep rift between the state and its citizens.

Many understood for the first time that this was a problem not only of their own making, the result of life circumstances or the choices they made, but part of something much bigger: long-standing government policies. This collective awakening cast light on the budget cuts and extreme privatization of the social services carried out by Israeli governments for almost three decades in all social spheres.

Government policies that extolled public sector cutbacks and transferred service provision – including social services – to market forces constituted a dramatic retreat of the state from its responsibility to ensure social rights in housing, health, education, employment, and welfare. The shifting of this responsibility to the private sector was carried out without sufficient attention to the social implications, and without offering alternatives to Israel’s citizens or the chance to cope with their diminished human rights. The results were felt by many – the drying up of numerous social services, the trampling of individual rights, and the dramatic deepening of social gaps in society.

This government policy was not accidental. It was born of a socioeconomic ideology that believes the free market should also deal with the realization of social rights. This system was and still is the norm in some countries, and is driven by parties with vested interests.

To institute this system, a number of mechanisms and methods were employed: As budgets were cut, many social services were privatized. At the same time, legislative initiatives to promote social rights were being thwarted. In addition, many laws to protect social rights that had already been passed were suspended by the “Arrangements Law”. Other laws were simply not implemented, due to various ploys used by the government. The legal system was also mobilized, with the courts giving legal backing to the government and the Knesset as they undermined the social safety net.

In addition to all this, Israeli tax policy was placed in the service of the market economy, with tax benefits serving the powerful and the tax burden gradually shifting to the middle class and lower income groups. The overall lowering of taxes combined with heavy security outlays meant that allocations to social services were at risk and then cut drastically.

To ensure that resistance to these policies would not gain traction, political leaders sought to undermine the potential opposition. Selective benefits were given to strong interest groups, for example, thereby silencing and weakening them; organized labor, which might have been able to prevent some harm to the labor market, was rendered impotent. Intense campaigns were waged to delegitimize all those adversely affected by the policies, particularly those who became impoverished as a result of these policies.

The research below sets out the mechanisms and methods used by various governments of Israel to shirk responsibility for ensuring social rights in the name of one socioeconomic ideology. As history has proven elsewhere, as well as in Israel, this approach is seriously flawed. It has wrought extensive damage to the systems of education, health, and welfare; led to a shortage of affordable housing; created a labor market with insufficient jobs; and made most Israelis vulnerable to unbridled competition, salaries that cannot meet the cost of living, and exploitive work conditions. Interspersed in this paper, we have placed interviews with individuals who once held key civil service positions, casting light on these methods based on their personal experience.

Education, health, housing, employment, and welfare are not commodities, but fundamental rights to which every individual is entitled. The governments of Israel must evince social responsibility and resume their obligations to ensure that every individual can fully realize these rights. Government policies are needed that promote social justice, reduce social gaps, and devote maximal public resources to ensure adequate social services. The demand for “social justice” by the tent protesters awaits meaningful change in government policy. This change will not be measured by declarations or promises, but by action. A significant component of this change must be relinquishing the mechanisms and methods described below that have been in place for years. We hope that revealing the mechanisms used to promote this economic system will help the public better understand government activity in the coming years, and allow it to make more informed decisions.

PART ONE: THE METHODS

Chapter 1: Drying Up Social Service Budgets

How the System Works

The primary tool used by Israeli governments to diminish their role in social service provision was the gradual but extensive reduction of the budgets of government ministries and public bodies that are responsible for the provision of these services.

The opening salvo for changing the socioeconomic orientation of Israel (the shift to neoliberalism) was the Economic Stabilization Program, introduced in 1985 to contain the soaring inflation of the 1970s and 1980s. This program included cutbacks in government spending, a reduced role for the state in service provision and subsidization of commodities, and stepped-up privatization. As a result of this plan, the budgets of the government ministries steadily declined, while efforts to privatize social services and public corporations steadily grew.

In the 1990s, the state budget was allowed to expand somewhat to allow for the absorption of waves of immigration from the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia. In the 2000s, when the government concluded that enough had been done to absorb new immigrants, it returned to the original plan and resumed the cutbacks. In 2003, the Socioeconomic Defensive Shield Operation was launched – an important milestone in the system that advocates reduced government outlays for social services.

The context for this economic plan was the recession following the outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada in 2001, the bursting of the high-tech bubble with its impact on Israel, rising unemployment, and a sharp drop in tourism. This economic plan called for sweeping cuts in the budget accomplished by a salary freeze, reductions in National Security Institute payments, raising the retirement age for pensions, reducing the concentration of wealth in the capital market, and instituting an across-the-board 4% cut in the budgets of government ministries.

Almost three decades of policies designed to reduce government spending led to a drop in public outlays from over 50% of the GDP in the 1990s to 42% of the GDP in 2011 – lower than the average of developed countries. And this came about at a time when the Israeli economy was showing steady growth.

When Israel’s heavy spending on security is taken into account, a very limited amount remains for social needs: Government civilian expenditures (government outlays minus security expenditures) are lower in Israel than the average of OECD countries, constituting 31.8% of the GNP compared with 40% on average in OECD countries.

The policy of reducing government spending is implemented through two primary mechanisms:

1. Budget cuts: These are cuts to the budgets of government ministries that are responsible for social service provision, or direct cuts to the budget of a specific office, often touted by Finance Ministry officials as in the interest of “greater efficiency”. Across-the-board cuts have also been made to government ministries and public authorities. Over the past decade, for example, the government has annually slashed the budgets of all the government ministries, with the exception of the Ministry of Defense. This has ranged from 1-5%, until 2006 when the Finance Ministry asked for a drastic across-the-board cut of 9% to finance the Second Lebanon War, but ultimately made do with a 6% cut thanks to public pressure.

These cuts are generally made via the Arrangements Law, which is passed together with the state budget and receives sweeping approval, as its rejection would cause the government to fall (see Chapter 3 below for more about the Arrangements Law). Thus reforms are approved annually that often include cutbacks and privatization of various ministry budgets without any serious deliberations. Furthermore, the process of submitting the budget has historically not been transparent, preventing ministers and Knesset members from thoroughly examining it, which allows the government to easily pass budget-cutting bills.

Passage of a two-year budget in 2009 was a milestone in the budgeting process. According to this new system, the Knesset will approve the state budget once every two years, rather than examining it anew annually. This system makes it easier for the government to introduce budget cuts because it eliminates the annual criticism and Knesset haggling over budget policies reforms and cuts.

2. Budget depreciation: To dry up a budget, it is not necessary to reduce it; one can simply not update it in keeping with demographic changes – population growth, increased numbers of elderly or children, changes in the proportion of people with special needs, etc. Thus, the budgets of some government ministries responsible for social services have remained fairly stable over the years, but the allocation has dramatically depreciated because of the increased number of people served by this allocation (more schoolchildren, more people in need of the healthcare system, etc.).

Examples of How it Works

As a result of years of cuts to the budget of the Ministry of Housing and Construction ‒ the ministry responsible for regulating the housing market ‒ the demand for apartments far exceeds the supply, and the housing assistance given to the poor is now meager or completely inadequate.

The budget of the Ministry of Education has sustained significant cutbacks over the years, which has led to lower wages for teachers, devaluation of the teaching profession, larger classes, and a trend toward privatization within the school system.

Public funding for the health system has steadily decreased over the past fifteen years. Reduced government spending on health and health services led to a significant increase in private spending for health services (see the interview with Prof. Gabi Bin Nun, former Deputy Director General of the Health Ministry, in the next chapter).

Over the past two decades, the budget of the Employment Service has been reduced and its authority curtailed. These cuts do not allow the Employment Service to adequately perform its functions (see the interview below of Rimon Lavie, a former senior official in the Employment Service).

Extensive changes have been made to the social safety net in Israel over the past several decades, with most of the budget cuts and changes to the eligibility criteria for pensions and allowances having been enacted through the Arrangements Law. For example, the income support payment, which is the last safety net for a family with no other income, has been depleted over the years in the wake of several budget cuts. Today it no longer allows for a dignified living or food security for families without assets or other income. Another example is unemployment insurance: Following sharp cuts in allocations to assist the jobless, the eligibility criteria for unemployment insurance are now so stringent that they deny support from many without a job, and the amount of the allocation itself has been reduced.

An Insider’s Look:

Atrophy of a vital government service on the way to privatizing it: The case of the Employment Service

Rimon Lavie, former Director of the Department of Human Resources in the Employment Service (1971-2005)

I worked in the Employment Service from 1971 to 2005 in a variety of positions, and I am sorry to say that I witnessed a long line of policy decisions that undermined the functioning and role of the Service, which, in my opinion, is the most important body in Israel for adding more people to the workforce.

Over the years, the budget of the Employment Service, its staff, and the tools at its disposal were steadily reduced, in complete indifference to the growth of the population, the civilian labor force, and the number of employers. Few tools were available to the Service, but some were developed outside it: Vocational training courses and occupational psychology tools were developed in the Ministry of Labor (later the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Labor). Professional training programs were spread among various government ministries, and low budgets were allocated that were insufficient to meet the demand. Also decisions about courses were made sporadically during the year, making it difficult to plan and refer people to them who urgently needed this training.

The budget cuts for professional training and the Employment Service, which had begun in the 1980s, were stepped up after 2003. Claims were made about the lack of efficiency and disappointing results, especially in light of direct reductions in transfer payments (unemployment insurance and income support payments). These cuts were also based on the “unprofessional” image of the Service, the rapid turnover of CEOs, and the unsuitable political appointments made there for many years, creating a vicious cycle that served to justify the Finance Ministry’s measures.

In the years 2004-2008, the Employment Service was forced to reduce its staff by a third, leaving it with 600 employees instead of 900. Many plans for reform and renewal of the Service were rejected out of hand or shot down by the Finance Ministry, in an attempt to make matters worse to clear the way for the privatization of labor force services, as part of the “flexibility” in which neoliberalism placed its faith. These ongoing cutbacks and the erratic budgeting of professional services primarily harmed the disadvantaged, who were already marginalized geographically and socially, since the better-off knew how to get services via other channels or their social networks. These policies also contributed greatly to the growth of middlemen and labor contractors, increasing the phenomenon of exploitive employment.

As a result, the Israeli economy today lacks any central government body to regulate the employment market. In a small market such as Israel, this means that there is no way to ease the pressures and crises. This split damages not just the Employment Service, but society at large and the economy: In a small employment market, particularly in peripheral areas, unbridled and uncoordinated competition over jobs spawns exploitation, use of the wrong tools, and a revolving door to gain the benefits that come with every “new” employee. The absence of an effective and efficient Employment Service and the competition over information sources and resources undermines equality of opportunity and efforts toward employment and social mobility.

An Insider’s Look:

Ongoing budget cuts: The case of Project Renewal

Hagit Hovav, Director of Project Renewal in the Ministry of Housing and chair of the Interministerial Committee of Project Renewal (1982-2002)

Can you describe how the budget policy was conducted in Project Renewal?

Budget allocations always arrived late. The Finance Ministry transferred the budget in late October, but by then the monies could not be used until the following year.

How were budget cuts made to Project Renewal?

The budget cuts took place in several stages: At the beginning, they would inform me that in the following year the budget would be reduced by a certain percentage compared with the previous year, without offering any explanation. Later, at the last minute, following coalition deals, money was always missing, and then an across-the-board cut of 2-5% would be imposed on government ministries, and then the question was ‒ what should be cut? It’s hard to cut jobs, of course, and easier to cut program budgets such as Project Renewal, so that’s what ended up being cut.

From a systemic perspective, what’s the problem with the policy of budget cuts to Project Renewal?

The policy of cutting budgets is not transparent. Because the budget is constructed according to the budget lines of the Ministry of Finance, it’s not possible to study issues according to a cross-section or conduct comparisons. In other countries, budget comparisons are done annually to see the extent to which the budget contributed to the efforts to end poverty.

What has ACRI been up to?

- In July 2011, the Public Network for Health Equity in Israel, of which ACRI is a member, presented the government and public with two position papers intended to better health care and to close existing gaps in health in Israel – including allocating sufficient budgets for the public health system, which has been consistently drained of its resources.

- In August 2011, ACRI published a report titled “What Happened to Us?” The report presented facts and figures that demonstrate how consecutive Israeli governments have shirked their social and economic responsibilities and dried up social services.

- In December 2011 ACRI teamed up with a number of MKs from the coalition and opposition to propose the Basic Law: Social Rights. This proposed bill seeks to ensure rights to appropriate housing, quality health care, and free education. This Basic Law would create a constitutional imperative to properly fund education, health care, and housing policies, reversing the decades-long trend of austerity that has perforated the Israeli government’s social spending.

Chapter 2: Privatization of Social Services

How the System Works

Social services are the basis for enabling the existence of a developed human society: A society cannot function properly without adequate systems of education, health, and welfare, without occupational development, and without ensuring that its members have a roof over their heads. Therefore, the extensive cutbacks over the past few decades in Israel, as described in the previous chapter, could not leave a vacuum.

To replace what was removed from the public systems, the government in some cases (such as welfare and employment), put social service functions into private hands. In other cases, when the government partially or completely abandoned service provision (such as education and health), the private market itself began to create alternatives for people who needed the service and had the wherewithal to purchase it. All these phenomena have been popularly termed “privatization”.

Privatization generally takes place during or soon after extensive cuts to social services, and in fact sometimes the purpose of these cuts has been to lower the quality of the government-provided service, using the decline in service to justify privatization. Other times, the privatization itself leads to a budget cut. This happens when a service is outsourced, and budgeted for less than when the service was provided by the public body. This is commonly justified by claims that the private market is more efficient and will do the job for less, even though the scope and quality of the service very often declines or turns out to cost more than when it had been provided by the government.

The subject of privatization is complex and controversial. While the premise is generally accepted that the state is responsible for the realization of social rights, opinions are divided about whether these services must be given directly by the state or can be provided by outside parties. We believe that the state is not obliged to provide all the social services itself, but that some services and powers should not be privatized. It is our opinion, for example, that a private service provider should not have the authority to decide on eligibility for that service, and should not have the authority that could deny someone’s human rights (such as making a decision to send someone to a closed institution).

Therefore, for all public services, the authority given to the service provider should be examined to decide whether this function may be privatized. The more vulnerable the population served – one that cannot stand up for its own rights – the more consideration should be given to whether privatization would be a good idea. In any event, it is critical that the state not abdicate its responsibility for provision of a social service after it is privatized – the state continues to have the obligation to ensure quality, accessibility, and equal treatment in provision of the privatized service.

The privatization of social services can be divided into two categories: One is the privatization of the provision of a service, meaning that the government transfers the responsibility for providing a specific service to a private party; clear examples of this are health services for schoolchildren and the centers for chronic treatment of drug addictions (“methadone centers”). The second category refers to privatizing the payment for the service; meaning that private parties – the citizen himself, donors, foundations, or nonprofits – become the primary financer of the service. Examples of the privatization of payments are the rising medical copayment fees – without which insured persons will not receive treatment – and the rising price of school tuition. The privatization of payments has transformed basic rights that the government must ensure, such as health and education, into commodities that are purchased by those who can afford it.

Privatization of the first type is initiated by the government (“top down”), while the privatization of payments fosters the growth of private initiatives (“bottom up”), which are eventually regulated by the government. On the surface, one might argue that this latter is not privatization because the government has not decided in advance to privatize, but in practice it is an inevitable byproduct of budget cuts, which ultimately damage the quality and scope of services. The drastic reduction of teaching hours in schools, for example, has led some principals to compensate by having Parents’ Committees finance enrichment and support programs out of their own pockets, or turning to nonprofits, foundations, and commercial enterprises who offer curricula and teachers. This is also true for the reduced “health basket” and the lengthening waiting lists for medical operations and treatment, which spawned a flourishing business of complementary health insurance and private health services.

The system is set in motion by several preliminary processes. One, as noted, is the ongoing budget cuts for social services; others are legislative initiatives that shrink the obligations and responsibilities of the public sector, or weaken labor unions, or thwart others who may voice objections to privatization. This combination of budget cuts and undermining of the legal and organizational opposition weakens the public services, forcing them to cooperate with private initiatives.

The Arrangements Law is a powerful tool for advancing privatization policies. The government sometimes uses the Arrangements Law to bypass normal legislative procedures in the Knesset and to enact far-reaching reforms that lead to privatization of the social services. This is the method by which significant cuts were approved for education and health, inter alia, which led to privatizing the payment for these services and instituting the Wisconsin Plan, which essentially privatized one part of the Employment Service.

Another tool for implementing privatization is outsourcing. Here a decision is made to transfer the service provision to private companies in a non-transparent, administrative procedure far from the public eye and media watchdogs. These services are awarded to private companies based on tenders, without the public or its elected representatives involved in the decision to privatize or the form it will take. In this way, for example, a range of welfare services was gradually transferred to private companies, leaving most Israeli welfare services provided today in private hands.

Another element of privatization is the adoption of free market models for managing public systems, such as schools and higher education, in a way that undermines fundamental rights and deepens inequality. For example, a “self-management” model was instituted in the school system, in which every school functions as an economic unit with a separate bank account, and the principal may make commercial use of the school facilities to make ends meet. Systems of measurement and evaluation from the world of business have been introduced to schools and universities: Just as the success of a commercial enterprise is measured by the profit to shareholders, so too schools are measured by their productivity and outputs. Entrepreneurship and outsourcing shift the functions of planning, management, execution, and quality control to the education nonprofits and commercial firms, functions that in the past had been performed by the Ministry of Education.

Another significant aspect of privatization in Israel is the lack of supervision and oversight of the firm that takes over performance or provision of a service. In general, after privatization of a social service, government oversight over the concessionaire that operates the service is sparse and inadequate. In the field of health, for example, the supervision of Natali, which provides first-aid services to 4,500 schools (in the framework of privatizing health services to schoolchildren), consists of one Ministry of Education employee, for whom this supervision is a small part of her job. In the field of welfare, most supervisory functions over the Wisconsin Plan were also transferred to a private company.

Privatization in Israel has become the default for every public service that has not functioned well or is in financial trouble. The starting point of decision makers in recent decades is that the private sector knows how to do everything better and more efficiently than the public sector.

Beyond the problematic nature of this approach, which turns rights into commodities, the process of privatization is also not democratic. Even though these processes have critical implications for the public, they are not transparent, they are sporadic, and they lack a rigorous decision-making process in which all the options for improving a given social service are carefully considered.

An Insider’s Look:

The Finance Ministry doesn’t see the sick people: Drying up and privatizing the health system

Prof. Gabi Bin Nun, former Deputy Director-General of the Ministry of Health (2003-2007)

I was an employee of the Ministry of Health for thirty years – from 1977 to 2007. In my last position there, I was Deputy Director-General for Health Economics. I know the health system up close, and I was involved in all the key crossroads and changes that took place there in recent decades.

I think the turning point in state social policies began in 1983, when the Israeli economy almost went bankrupt. Ever since, economic policies became much more aggressive in reducing the state budget, lowering the deficit, and strengthening free market mechanisms to stimulate growth and efficiency. This policy was embraced over the following years by both right- and left-wing governments, equally. It began more moderately and grew more and more aggressive over the years.

The Budget Division’s influence over Israel’s economic decision-making is much greater than in most western countries. In my opinion, this excess power of the Ministry of Finance divisions harms the principles of democracy. Budget Division officials serve only for one brief term. During that term, almost the only measure of their success is the extent to which they managed to constrain and cut the state budget. What is the price society pays for this policy? What are the long-range, macro-economic implications of it? These questions interest virtually nobody. This is a short-sighted policy. The Finance Ministry’s control over the budget and its absolute control over the wording of the Arrangements Law make it an exceptionally powerful force.

This can be illustrated by the case of the National Health Insurance Law. This law was passed despite the professional opposition of Budget Division officials because the law undercut their agenda of reducing state involvement and funding for social services. The National Health Insurance Law anchored a social right in legislation and ensured the health system of an allocation earmarked for health. From the perspective of the Ministry of Finance, this law conflicted with the policy they advocated. Suddenly, the Ministry was obliged by law to earmark money for health.

As soon as the law was passed, the Ministry began to put forward ideas that would cumulatively have rendered the National Health Insurance Law meaningless. It proposed, for example, that Health Funds be allowed to compete over the price of the insurance premium or allowed to offer different health services – a proposal that would virtually defeat the point of the law. The Ministry did not manage to pass these proposals, but in 1996 they had a new idea: cancellation of the parallel tax – the tax employers had to pay as a contribution to the health insurance of their employees. The parallel tax and the health tax together comprised the main sources of funding for the National Health Insurance Law. The economic idea underlying this arrangement was that these sources were linked to Israeli economic growth ‒ as long as the economy grew, there would be enough money to fully fund the health system without the need for a state budget allocation.

The Ministry of Finance understood, however, that not needing state funding meant that it would lose its power to influence the health system. Therefore, it requested that the parallel tax paid by employers be cancelled, and it offered to make up the difference from the state budget (at that time it was NIS 5 billion). Indeed, after the parallel tax was revoked, the Ministry of Finance transferred money from the state budget, thereby restoring the mechanism that enabled it to control the flow of funding to the health system. Thus, the Ministry of Finance, which had objected to the National Health Insurance Law, found a way to override it and perpetuate dependence of the health system on the state budget.

At a later point, the Ministry of Finance inserted into the Arrangements Law a provision that would allow the Health Funds to sell supplementary insurance policies. These policies have grown significantly. Today they cover some 75% of the population, with a turnover of approximately NIS 3 billion. This tsunami of money has completely changed the rules of the game today, because instead of budgeting the system, the Ministry allows private money to flow into it. Although it pleases the Ministry to have private money covering health costs (as this money replaces state funding), this trend harms the public and the egalitarian nature of the health system, because only those who can afford it purchase the supplementary policies.

In summary, it can be said that the Ministry of Finance has managed to invest the health system with much of its own ideology, as it brought about far-reaching changes to the character and substance of the National Health Insurance Law and the entire health system. Tragically, many of these decisions were not taken by the government or the Knesset, but by officials in the Ministry of Finance.

What has ACRI been up to?

- ACRI has long been involved in fighting against privatization processes led by consecutive Israeli governments. In July 2011, for example, ACRI submitted a position paper to the Knesset, stating that it is strongly opposed to the continued privatization of student healthcare in schools, and calling on the Ministries of Health and Finance to return this service to the authority of the Ministry of Health. ACRI’s position is that such an important service must remain in the hands of the State, and that privatization of healthcare harms socio-economically disadvantaged communities and those living in the peripheries.

- ACRI has been a leading advocate against the so-called “Wisconsin Plan” (Welfare-to-Work), which has severely violated the right to life and work in dignity of tens of thousands of Israelis, and together with others managed to stop it. In April 2010, in response to ACRI’s petition against this plan, the State announced that the program would end and not be renewed. This program gave sweeping authorities to private agencies over the lives and very dignity of thousands of individuals. In the petition, ACRI stated that the extreme privatization characterizing the Wisconsin Plan has caused the violation of participants’ rights – their dignity, their freedom to choose, and their privacy. For these and other efforts, the Israeli Employment Service gave ACRI a certificate of appreciation in February 2012.

- In August 2012, following a petition by ACRI and Physicians for Human Rights – Israel, the Health Ministry announced the cancellation of a tender that would have bestowed the administration of methadone distribution centers for drug addicts in Israel to private companies. The petition included a detailed list of potential harms privatization would have on the centers’ clientele. Among the inadequacies of privatization: it would encourage the winning bidder to limit treatment given that each center operator is paid for the number of clients and not the type of treatment. The petitioners argued that because there is no clear definition of the psychosocial services they should provide, the most inexpensive approach would be to offer drug substitutes with a minimal amount of social support. Ultimately, the privatization of the centers would not require the companies to provide effective and substantive care to the patients – and would not contribute to their recovery.

Chapter 3: Revoking or Suspending Social Legislation through the Budget Arrangements Law

How the System Works

Many have observed that the infamous Arrangements Law has been the main instrument in recent decades for imposing government policy in social and economic matters. Instead of engaging in parliamentary debate about each law, one at a time, governments have used the Arrangements Law once a year to seal the social fate of the public in one fell swoop.

The Arrangements Law was created in 1985 at a time when the Israeli economy was deeply mired in crisis as inflation raged at hundreds of percent. Prime Minister Shimon Peres and Minister of Finance Yitzhak Moda’i came up with an economic plan to stabilize the economy, a plan contingent upon comprehensive changes in a number of areas including privatization of government corporations, lower wages, and legislative amendments. Although amending legislation is a lengthy process, requiring several stages of bringing the bill to the Knesset plenary and committees, an economic plan was urgently needed and so the government decided to introduce all these changes in one law – the first Arrangements Law. The intent was to pass all the legislative amendments required to implement the plan at one go. Besides saving time, the government hoped that incorporating all the changes into one omnibus bill would also cut down on some of the opposition by Knesset members, the Histadrut Labor Federation, and the public at large, as some proposed amendments were in clear contravention of existing laws and agreements.

Ever since, however, the law, originally intended to be a one-time-only emergency measure, has become routine, tabled annually for 27 years for the approval of the legislature in tandem with the State Budget Law. The Arrangements Laws, sometimes called the “Arrangements Law”, and sometimes appearing under other names (the Economic Policy Law or the Israeli Economy Rehabilitation Program Law), include a great many laws and amendments not directly related to the budget, and serve the government as a powerful tool for implementing policy and economic programs.

The Arrangements Laws have also served to overturn statutes to which the Ministry of Finance had objected from the outset because of their budgetary implications. For example, the Public Housing Law was revoked, state health insurance was reduced, free preschool education was deferred, violations of the rights of contract workers were approved, and a long list of National Insurance Institute allowances were cut back. In practice, this law became a key coalition tool to carry out economic reforms and social-economic policymaking. The fact that the law allows the government to fast-track major reforms and to overturn duly enacted legislation flouts the work of the Knesset and turns it into an arm of the executive branch.

Despite the changes introduced over the years to the procedures for enacting the Arrangements Law, it remains an improper way to fast-track bills that contain a mass of laws and amendments, some dramatic and having far-reaching implications and impact, brought to the Knesset floor as a single package with a tight deadline that does not enable an orderly, in-depth legislative process as would be required for each provision on its own. This abbreviated process hinders effective supervision and oversight by the public, by the governmental ministers for whose ministries some of these amendments are relevant, and primarily by the Knesset itself and its committees.

Another criticism of the Arrangements Law is that the government opportunistically takes advantage of it to set in motion extensive economic reforms, and to pass laws that are not related to the budget. For example, in the 2003 Arrangements Law, structural reform of the agricultural councils was enacted; in the 2004 Arrangements Law, a welfare and employment policy reform was passed in which the Employment Service was partially privatized (via the Wisconsin Program); in the 2005 Arrangements Law, the licensing system of regional radio stations was reformed; and in the 2006 Arrangements Law, the Water Commission was turned into the National Water and Sewage Authority, and its tasks, authority, and structure were transformed. And this is only a partial listing.

Another problem with the Arrangements Law is that the entire package of amendments and reforms is automatically approved, as both coalition and opposition invoke party discipline to control the votes of their members – one vote on a range of issues. The law is presented by the government as a package deal in which the components are interdependent, and that only approval of the entire package will enable proper implementation of the budget.

Sometimes, even when the Arrangements Bill is not linked to the budget deliberations, the government declares that failure to pass it would constitute a vote of no-confidence, thereby ensuring coalition discipline in the vote. Thus, the Knesset is undermining itself when, out of coalition considerations, it approves legislation that revokes or suspends laws that it itself passed. In this absurd situation, Members of Knesset who supported laws that passed by a large majority in normal legislative procedures find themselves voting to revoke these laws via the Arrangements Law.

An Insider’s Look:

The Arrangements Law: Far-reaching implications for poverty levels and inequality

Prof. Leah Achdut, former Deputy Director for Research and Planning in the National Insurance Institute (NII)

What policy has motivated use of the Arrangements Law?

This law has allowed policymakers to achieve their goal – not just stimulating growth, but effecting profound changes in the size of the government – public spending. From 1985 to the early 2000s, public spending declined from approximately 70% of the GDP to some 50-52% of the GDP. From the early 2000s, and particularly in 2002-2003, the Arrangements Law served the policy and ideology that advocated the transformation of big government into small government in which, through budgetary changes, the government would be less involved and provide fewer services, particularly social services. When a government provides fewer services, it needs less income from taxes, and therefore a long period began of lowered taxes in conformity with the view that the government had to withdraw from its deep involvement in social and economic matters. The moment the state reduced public spending and the tax burden, the effect was a pincer-like movement ‒ increasing economic gaps in Israeli society and abdicating its role of reducing inequality and poverty.

Were policymakers aware of the implications this law would have for deepening inequality and poverty in society?

When we first saw the Arrangements Law of 2002-2003, and actually already in 2001, we in the NII were shocked by the extent of the cuts. The Bank of Israel was partner to this strategy in terms of lowering public spending; it did not make its voice heard. The NII decided that we had to bring to the attention of the Knesset and the public at large an analysis of the anticipated repercussions of the policy proposed by the Ministry of Finance. Time was short, but with the collective efforts of the staff at the NII’s Research and Planning Division, we prepared a document and presentation that illustrated in words and figures the long-range impact of cutting the income support payment, which was lowered by about 35%, and the child allowance, which was sharply reduced. We clearly showed that these cuts would widen the social gaps. In retrospect it turned out that our estimates were accurate. The presentation and materials were also brought to the attention of the Minister of Finance, as well as all policymakers, Knesset members, and the media, although it [the presentation] was not shown at the government meeting. The NII forecasts were not challenged professionally on any level, but its approach and positions did not win support. The approach taken by the Ministry of Finance prevailed, even in some of the financial press, which expressed the view that those who receive stipends are generally shirkers of work, and therefore do not deserve guaranteed benefits or a reasonable minimum income.

What made it possible to use the Arrangements Law in this way?

It was a government constellation with a very clear orientation. The media were also in the thrall of this concept. The Bank of Israel also held its peace, and only discovered after three or four years how large the impoverished population had become.

What has ACRI been up to?

- ACRI has consistently detailed how the Arrangements Law is used as a tool to advance harmful reforms and privatization processes and to freeze legislation promoting social rights.

- ACRI is a member of the Forum of Organizations for the Cancellation of the Arrangements Law. The Forum’s efforts were one of the contributing factors to the procedural improvement, in recent years, in the legislation process of the Arrangements Law. For example, the various topics in the law are now sent in an orderly fashion to the relevant Knesset committees for discussion, and are no longer brought to the Finance Committee as a single package as was the case in the past. Additionally, each year, due to the work and comments of ACRI and other organizations in the Forum, various provisions are removed from the Arrangements Law and transferred to the relevant committees – especially provisions that entail far-reaching reforms with significant implications.

Chapter 4: Thwarting Legislation that Promotes Social Rights

How the System Works

Legislation is key to anchoring social rights and obligating the government to ensure their realization; the law should reflect the policies implemented or desired, give it legal authority, and ensure its administrative regulation. Therefore the government, in addition to promoting its desired political initiatives – often accomplished in Israel via the Arrangements Law ‒ also works to block bills that are incompatible with its social or economic philosophy.

While governments were implementing their policy to reduce state-provided social services, many attempts were made in recent decades by Knesset members who sought to challenge this policy by tabling bills that would expand the social rights of Israelis. The governments managed to obstruct passage of most of these bills, and resorted to coalition discipline when a majority of Knesset members were in support of a social rights bill that was “in danger” of passing. All this because the government did not want to be obligated to guarantee social rights, which would mean spending more money.

Thus thwarting bills became another method used by governments to bolster their policies and ‒ because the government has an assured majority in the Knesset ‒ it always has the upper hand. As a result, the Israeli law books lack social security legislation that would anchor the state’s obligations in these matters, laws that are common in many western countries.

Israel has no law, for example, that anchors the right to housing or the obligation of the state to provide housing to those eligible; public housing and housing assistance are addressed only by internal procedures of the Ministry of Housing, not laws. Similarly, the right to an adequate standard of living and the right to professional training are missing from Israeli law, to mention only a few.

Even for rights covered by laws, such as education and health, not all aspects of these rights are regulated. In education, for example, the law does not establish a minimum number of learning hours per child or free preschool education. The obligation to provide health services to everyone equally is also not defined. Although the law calls for medical care based on the principles of “justice, equality, and mutual assistance” and stipulates the right to services of reasonable quality within a reasonable period of time and distance from one’s home, these are not spelled out in clear standards for the Health Funds. Furthermore, vital health services such as dental care, mental health care and institutionalization, and nursing care remain outside the public basket of services and lack a precise definition of eligibility.

Many efforts were made over the years to change government policy in each of these areas ‒ to advance laws that would ensure greater realization of these rights. Creative proposals were tabled to effect changes, both small and large, that might be acceptable to a Knesset majority. Often these bills passed the first reading, but then the government imposed coalition discipline, preventing the bills from being enacted into law.

An Insider’s Look:

Lacunae in social legislation: Ministry of Finance control over the government discourse

Atty. Joshua Schoffman, former Deputy Attorney-General (1995-2009)

During my years at the Justice Department, I followed the legislative progress of social issues; in retrospect, I would be hard pressed to say that the governments of Israel had a comprehensive social policy. The social ministries make an effort to fulfill their duties, and sometimes manage to promote positive social initiatives, but the over-arching policy is set by the perspective of the Ministry of Finance, specifically the worldview that seeks to reduce the public sector. It is no coincidence that the government asked the Finance Minister to head the Socioeconomic Cabinet (as the permanent substitute for the prime minister).

In the absence of a coherent social philosophy and because the social ministries have a hard time advancing their own initiatives when they entail more funding or staffing, deliberations about social issues over the course of the year revolve around private members’ bills. Sometimes these bills spur the government to act, such as those that led to legislation of the Public Defender Law and the Equal Rights for People with Disabilities Law. But many private members’ bills are specific to an issue or sector, and do not reflect a comprehensive social perspective or consideration of the needs of the entire population. The position of the government and coalition about private members’ bills is often influenced by political interests or pressures.

The main government decisions that impact social services are made within the framework of the annual (or biannual) budget discussions. If you have not seen a budget meeting of the government, you have not seen a truly awful decision-making process. The government has before it the budget bill and a hundred or more draft resolutions. Resolutions that would require amendment of primary legislation are incorporated into the Arrangements Law and submitted to the Knesset without the normal procedure of a memorandum and substantive discussion in the Ministerial Committee for Legislation. All the resolutions are deliberated together, and a vote is taken on the entire package. These matters may be completely unrelated – health services and reform of the ports, marketing agricultural produce and reductions in the NII allowances, cellular communications and policies for higher education. All they share is that these resolutions were the product of the Budget Division, whether as initiator or adopter and promoter. The resolutions about health, for example, emphasized competition among the Health Funds, not expanding their services. Every year, the resolutions about national insurance deal with preventing fraud, not necessarily with providing protection for the innocent who are eligible for the allowances.

Although the Ministry of Justice tries to influence the substance in order to prevent harm to social rights, these efforts, as results indicate, were not always successful. The legal advice that the Ministry can give the government to prevent submission of a government bill is limited to situations in which the law, if passed, would not be constitutional. These situations are rare, particularly in light of the lack of court rulings – until recently – that nullified primary legislation because it undermined the right to dignity. In some cases, however, the Attorney-General did prevent submission of a bill that would have harmed social rights. For example, a bill was disqualified that sought to deny income support payments to anyone under the age of 25. Bills were also disqualified that sought to deny subsistence allowances as a punitive measure.

What has ACRI been up to?

- As the Knesset continues to block legislation that would guarantee basic social rights to necessities like housing or health care, ACRI continues to document government efforts to thwart bills that promote social rights and works with other to promote such bills.

- Some recent examples of legislative initiatives that ACRI was involved in promoting, often in the face of government attempts to block them: including affordable housing in the National Housing Committees Law; stopping the privatization of healthcare in schools; struggling against legislative attempts to raise women’s retirement age; a reform in nursing care and hospitalization that was initiated by the Deputy Health Minister following a bill drafted by the Coalition for Including Nursing Care in the Healthcare Basket, of which ACRI is a leading member; and the proposed Basic Law: Social Rights mentioned above.

In June 2010, the Coalition for Public Dental Health, of which ACRI is a key member, achieved a landmark legislative victory when the Knesset’s Labor, Welfare, and Health Committee approved a pilot program to provide dental care to children as part of the universal basket of health services.

Chapter 5: Non-Compliance with Laws or Court Rulings

How the System Works

Another way to ensure the effectuation of government policy, in addition to preventing social security legislation or revoking it via the Arrangements Law, is to disregard existing legislation that instructs the authorities to grant social rights, or to ignore court rulings that call for the realization of these rights.

The most common method to sidestep laws is to fail to allocate sufficient funding for them. For example, although workers’ rights are anchored in various laws, some of these are not enforced because the bodies charged with supervising compliance are not adequately funded; this is also the case for ensuring the education mandated by the Compulsory Education Law, but not enforced for the Arab populations in the Negev or East Jerusalem.

In other cases, specific provisions of a law are not implemented because they are dependent on the relevant minister enacting regulations for implementation of them. In too many cases, the ministers and ministry officials choose not to enact regulations, and this also happens with government decisions that require detailed procedures for their implementation. When the regulations, rules, or procedures are not issued, the law or decision cannot be fully implemented, and the result is that rights anchored in law become a dead letter. This is the case, for example, with regard to accessibility of public places for the disabled or the laws requiring integration of the disabled into the workplace.

The disregard of court rulings by the authorities is particularly disempowering for an individual because litigation is an attempt to solve a problem of non-compliance with the law – if the court ruling is not carried out, appellants remain powerless to bring about implementation of the law. Note that appealing to the court does not automatically grant relief because not all petitions are accepted and court cases can be time-consuming and endless. Even after a ruling, the implementation of decisions can be gradual and take years, if at all. And sometimes the state chooses to disregard the ruling, to defy deadlines set by the court for correcting a failing, or to continue to interpret the law as it sees fit.

In a memorandum sent by Atty. Yehudit Karp, former Deputy Attorney-General, to Yehuda Weinstein, current Attorney-General, she reproaches the state for its failure to comply with court rulings and warns of a widespread phenomenon that endangers democratic rule in Israel: “The increasing number of cases in which the government, responsible for safeguarding the rule of law, lends a hand to non-compliance and even contempt of the court, suggests that these are not just coincidental and marginal cases of government bureaucracy, but a systematic and conscious disregard of the obligation to carry out court rulings. This is a real and immediate danger to democracy, to the rule of law, and to the principle of the separation of powers in Israel”.

In response to this memorandum, the Ministry of Justice explained non-compliance with court rulings as due to “the extreme complexity of these cases, some of which entail significant budget expense, some of which have implications for third parties, and some of which require the establishment of new procedures and various complex administrative actions. Because of their complexity, these court rulings require an extended period during which they can be implemented”. Put simply, the state claimed that the rulings were not carried out or were significantly delayed because implementation was complicated and at times expensive.

This explanation is unsatisfactory. Delays and postponements in implementing court rulings and repeated requests for deadline extensions are precisely the sort of conduct the court has criticized and sought to prevent. Moreover, the complexity and cost of implementation were known to the justices when they formulated their conclusions and yet they instructed the state to implement a just resolution. Hence, considerations of cost and complexity cannot serve as a justification for non-compliance, as the court took them into consideration and ruled nonetheless that the steps must be taken.

An Insider’s Look:

With or without legislation: Erosion of government support for housing

Dr. Chaim Pialkof, former Director-General of the Ministry for Construction and Housing (2007-2009)

Anchoring a right in legislation does not guarantee that it will be safeguarded or budgeted, or that the goal has been achieved. The Housing Loans Law, for example, was intended to provide universal assistance, but it did not establish a right to housing. The more the tools are anchored in laws or regulations, the more protected they are from budget cuts, but, on the other hand, the more difficult to change. The prevailing approach at the Ministry of Housing – and perhaps it is incorrect – is that this flexibility allowed the clerks to sidestep the transitory changes made by politicians. This makes housing vulnerable to budget cuts, however, and is perhaps a heavy price to pay.

And budgets have been slashed over the past decade. These are but one sign of the deep budget cuts in social areas and welfare. At the same time, some advocated for shifting some of the functions to private firms. This transition does not always manage to fully address the needs, particularly for the disadvantaged. For example, transferring to mortgage banks the power to help individuals purchase an apartment allowed for decentralization of the service. You didn’t have to go to the Ministry of Housing to take out a mortgage, but only to one of the bank branches, and this improved accessibility. About five years ago, however, the government decided that banks will not only be mortgage providers, but also actually supply the financing. This adversely affected the willingness of the banks to give high-risk mortgages. This is an example of outsourcing that could be positive, in contrast with cases in which it could be problematic.

The decision-making process of the government for policy or structural changes is not sufficiently thorough, not just in the realm of housing. When some hundred draft resolutions about structural changes are presented to the government in its budget deliberations, the ministers have no time to absorb their meaning and the public has no opportunity to give feedback. In many countries, consultation is obligatory. The English do it via “green papers”, which are drafts made public on which there is broad debate. There are no surprises. In Israel, on the other hand, the government fears that divulging its position will lead to protest by organizations and court petitions. I understand the government’s position, but there is room for more thoroughness and also greater transparency, even at the stage of examining alternatives. The government does not sufficiently consider alternatives. The government usually makes basic decisions without considering other options or an adequate and thorough evaluation of the implications of the decisions.

The protest shined a spotlight on housing, but the more public attention turned to social justice, housing slowly fell out of view. The spotlight dimmed. The protest declarations and statements of the alternative committee had no effect. In my humble opinion, the Trajtenberg Committee was not sufficiently transparent, did not elaborate on the implications and alternatives, and gave no indication of costs. That Professor Trajtenberg went to talk with people was nice, but it would have been more significant had he presented a draft for public discussion and comment. At any rate, the public protest created change by virtue of raising the issues, but I do not see that it led to structural change.

What has ACRI been up to?

- Part of ACRI’s ongoing work is to document and make public government attempts to avoid implementing court rulings or constitutionally mandated social policies – for example as part of the extensive report published by ACRI’s Project Democracy in 2011.

- In early 2010, Attorney Yehudit Karp, a former Deputy Attorney-General, sent a detailed memorandum on the subject, based on cases handled by ACRI, Yesh Din, and Adalah, to the Attorney-General, who following that published relevant directives on this matter, noting that ” compliance with court rulings is incumbent not only upon the residents of the State and those who enter its borders, but first and foremost upon the State itself.”

ACRI also struggles against the increasing legislatives attempts to weaken the Supreme Court, and in February 2012 published a detailed position paper on this mater, titled “Supreme Court under Attack,” which was also sent to relevant decision-makers.

Chapter 6: Tax Policies that Reduce Social Spending and Widen Social Gaps

How the System Works

Israel’s natural resources have not yet brought much currency into the state coffers, and therefore the way to ensure adequate social services and the realization of social rights is through taxes paid by its citizens. Lowering taxes harms the ability of the state to accomplish this. And yet the socioeconomic approach of Israeli governments over the past decades has been exactly this: Ease the tax burden and shrink government spending, primarily on social services.

In recent decades, Israeli governments have more and more adopted the policy of reducing taxes; today, the tax rate in Israel is relatively low compared with other countries. As a result, the state coffers have less and less money to spend on public needs. Thus, public spending in Israel has dropped from over 50% of the GDP in the 1990s to 42% of the GDP in 2011 – less than the average in developed countries. And this comes at a time when the Israeli economy has been in a period of steady growth.

After the huge outlays for security, very little of the budget remains for social needs. Security outlays today reach almost 12% of the GDP, meaning not only is there less for public spending, but even less for social spending. Indeed, in comparison with developed countries, social rights spending is very low: Israel is today ranked 28th of 34 countries in percentage of the GDP spent on health, income allowances, pensions, and other social services.

It is not just that the tax burden in Israel has eased over the years, but that the tax reductions were applied primarily to direct (progressive) taxes, in which the amount paid increases with one’s salary. Examples of direct taxes are income tax, national insurance, and health tax. On the other hand, indirect (regressive) taxes have remained high: These are taxes like VAT paid by the public on purchased products, regardless of income. Thus, easing the tax burden was beneficial primarily to those in high income brackets, while the tax burden on lower-income people remained high.

As a result of the drop in direct taxes, Israel’s taxation system is considered one of the least egalitarian among OECD countries. Already in 2009, state revenues from indirect taxes exceeded its revenues from direct taxes. In June 2011, the Ministry of Finance forecast that state revenues in 2011 from indirect taxes, primarily VAT, would reach NIS 104.6 billion, compared with NIS 103.5 billion brought in by direct taxes.

The prevailing view in the Ministry of Finance is that lowering taxes will stimulate the economy because it encourages investments, which will raise income levels. According to this view, the income “trickles down” to all Israelis. In practice, however, growth in Israel has not brought economic betterment to everyone, but only to those who directly enjoy greater income.

As a result of this system, lower-income Israelis are harmed in two ways: They both pay higher taxes relative to their income and they receive fewer benefits because of reduced government spending on social services. It would be possible, of course, for the state to take a different route ‒ to increase the tax burden or reduce government outlays in other spheres, rather than social services. Those with higher income can, of course, pay for health services, education, and the like, but most of the public cannot afford all these expenses, hence, their basic rights are being violated.

An Insider’s Look:

Tax reductions: Neither effective nor helpful to the needy

Prof. Yaron Zelicha, former Accountant General in the Ministry of Finance (2003-2007)

As the former Accountant General, what structural problems did you see that have a direct impact on the realization of social rights?

I saw several things. First, regarding taxation: I saw people with low income paying income tax and making social security payments. There might be some logic in paying social security, but income tax? What logic can there be for a country to tax its poorest citizens?

The second was state support for nonprofits. The state would give out billions of shekel to all sorts of organizations that help the poor or those who need support. The problem was that by law, the state must distribute its monies according to impartial and non-discriminatory criteria, and this was not happening. Some criteria were biased and almost none were transparent. In the Accountant General’s office, we mapped out all the criteria and posted them on the Internet so that every citizen could see that the moneys were being equitably distributed. Regarding state grants, it turned out that the government did not monitor the overhead or general expenditures of the nonprofits receiving the money. We found that over 90% of these organizations spend more than 50% of the grant money on administrative or general expenses. Starting in 2004, we enforced rules that these expenditures can be no more than 7-20%, depending on the size of the organization, and we thereby saved budget monies that had been going for these grants.

In your opinion, how does the Israeli tax system contribute to widening the social gaps?

The decision makers are not particularly aware of the social implications of their decisions – and also not of their economic effectiveness. In Israel’s macro-economic situation, with private consumption low, it makes sense to lower indirect taxes, which are regressive, not progressive. The [current] policy is ineffective economically and socially because the tax burden is not rational.

Two contradictory tax measures were taken: The first was to lower the company tax rate: This was an incorrect decision. Although on principle it is always smart to lower taxes, the question is: Which taxes and in what order. Indirect taxes should have been lowered, not the company tax. And from the moment they reduced the company tax – even though that was not a good decision – it was a colossal mistake to restore it. Why? Because you create uncertainty – the belief that every tax reduction can be overturned, though tax reductions are intended to stimulate certain economic activity. If you lower taxes and a year later you cancel the reduction, people will not start businesses or expand them out of fear that the reduction was just a ruse. Second, lowering the company tax increased the value of the companies listed on the stock exchange, and now there are downturns because of the crisis globally and in Israel. If you raise the company tax at a time like this, you are accelerating the market drop, which hurts pension savings and deepens inflation.

What has ACRI been up to?

- ACRI, together with Adalah, successfully petitioned the High Court of Justice against part of the law amending the Income Tax Ordinance, which was deemed unconstitutional because it offers tax benefits to specific communities without egalitarian and clear criteria. Even though Arab communities are at the bottom of socioeconomic rankings in Israel, not even one of them was included among those eligible for benefits.

Chapter 7: Eliminating the Opposition

How the System Works

A critical component for advancing these destructive socioeconomic policies has been contending with the opposition that might challenge them. Over the years, opposition in Israel to the governments’ efforts to shirk social responsibility was handled in several ways. The primary method was to eliminate any opposition that could be eliminated and to co-opt the powerful, primarily specific sectoral groups that could ensure a strike-free economy.

For example, opponents to the socioeconomic policy were regularly labeled “irrational.” Disadvantaged groups – the poor, Arabs, ultra-Orthodox – were described as “parasites” or “lazy,” and claims were made that they “don’t try hard enough” or “bring too many children into the world that are born into poverty.” The delegitimization and encouragement of racism toward these groups brought about two related outcomes: Public discourse was diverted toward those in protest of the socioeconomic policy, rather than to the shortcomings of the policy, and, second, the governments were not compelled to change their ways.

Another target in the opposition was organized labor, which had the power to protect the erosion of workers’ rights and salaries. To alter the power balance between employers and employees, many steps were taken to break organized labor, and new rules were instituted about labor relations in the economy. These changes, including the privatization of government corporations and services, and the employment of contract workers, had the effect of disempowering workers, chipping away at their rights, and widening the economic gaps.

Another mechanism for eliminating opposition involved a change in the welfare policies – the widespread use of what is called “categorical transfer payments,” which are given to specific population groups based on their ethnic origin, national origin, or military service. The high proportion of such payments in Israel not only entrenches inequality, but even worsens it, engendering rifts between disadvantaged groups. These divisions hamper efforts to work together on social issues that are not sectoral, enabling the government to continue these socioeconomic policies for many years.

What has ACRI been up to?

A main part of attempts to eliminate the opposition targeted organized labor. As an antidote to this method, ACRI is involved in the Workers’ Rights Forum, which works to protect and promote organized labor and to promote direct employment (as opposed to the increasing phenomenon of contractor employees).

As part of ACRI’s ongoing effort to promote organized labor, we have recently awarded the 2011 Emil Grunzweig Award to Koach LaOvdim – Democratic Workers’ Organization, which organized thousands of workers from a wide variety of occupations – in the public sector, in the private sector, in the service industry, and even in civil society organizations.

Chapter 8: Legal Backing for Weakening the Social Safety Net

How the System Works

In recent decades – with increasing frequency and as social services receded – the courts have been asked to step in to protect social and economic rights. Dozens of petitions were filed regarding socioeconomic legislation, against government decisions, and against administrative decisions that adversely affected the realization of these rights.

The legal system was asked to adjudicate instances of harm to the social safety net on four general levels: petitions to nullify laws that reduced or suspended social rights; petitions to enforce laws that established rights, but were not implemented by the government; petitions against administrative decisions that undermined social rights; and petitions against policies or laws that discriminated against a specific population group, depriving them of rights.

Although the existing Basic Laws do not explicitly protect socioeconomic rights, the Supreme Court recognized some social rights as fundamental – derived from the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty and other laws that anchor social rights. For example, the right to social security was recognized as fundamental, as were the right to education and the right to a life of minimal dignity. However, the Supreme Court took a more restrained approach in its rulings on petitions against government policy in this area. Since these petitions raise questions of social justice and resource distribution, the court refrained from a review of primary legislation, secondary legislation, or government decisions and regulations having to do with social and economic matters.

In practice, although court rulings indicate that the court recognizes social rights as worthy of protection, the scope of these rights – their substantive content – is considered the bare minimum. The court was most likely to intervene in cases of discrimination or where the government is legally obliged to allocate resources, but fails to do so. For example, the High Court of Justice invalidated a government decision on National Priority Areas as it discriminated against Arab towns in the allocation of education budgets. In another case, the High Court obligated the government to bear the education costs of east Jerusalem students who could not be accommodated in the local public schools. In such cases, the court justified its intervention in terms of preventing harm to human rights, as stated by Aharon Barak, former President of the Supreme Court: “Protection of human rights costs money and a society that respects human rights must be prepared to bear the financial burden.”

In this context, we also cite the recent ruling by former Supreme Court President Dorit Beinisch issued upon her retirement, which intervened at a higher, constitutional level to prevent harm to the right to dignity. Unusually, the court ruled to nullify a provision in a law that would have denied income support payments to someone who owns or uses a car. This precedent-setting judgment asserted that the law was too sweeping – it presumed that anyone with a car does not deserve this payment – and it fails to give the applicant an opportunity to prove that his or her earnings are insufficient despite access to a car.

In the framework of this ruling, the court stated for the first time that there is no distinction between social rights and civil rights in terms of the state’s obligation to ensure their realization and allocate funds to that end. In recent decades, this concept has been accepted in various western countries and the human rights community, but until now, there was no clear statement by the Israeli Supreme Court, hence this is a significant step forward in the protection of social rights.

But even in this ruling, no definitive standard was set for what constitutes a life with dignity that the state must safeguard, nor does it stipulate that this standard must ensure adequate living conditions, but only minimal conditions to prevent scarcity that poses a threat to survival. Thus the courts continued the trend of failing to give concrete definition to the state’s obligation to ensure social rights. In recent decades, the court tended to reject petitions that sought relief from authorities that do not fully implement laws that grant social rights, or in which the court is asked to nullify government decisions that curtailed social rights of the public at large. This was the case, for example, in rulings about reduced old-age pensions, cuts to income support payments, harm to the right of special needs students to be mainstreamed, shrinking benefits to people with disabilities, privatizing medical first-aid services for schools, etc.

The main argument used by the court for not intervening in socioeconomic matters is that state resources are limited and therefore decisions about how to divide them up are made by the elected representatives. This argument is based on the view that social rights are expensive, even though the recognition has emerged in Israel and the world in recent decades that civil rights also involve significant allocations, and therefore budgetary distinctions between types of rights are invalid.

Beyond this first argument by the court – that it should not intervene in budgetary considerations of the executive or legislative branches – another key argument in its rulings has been the competence of the court to make economic judgments. The judges have noted that the court is not an expert in economic matters and, furthermore, cannot anticipate the budgetary implications of its rulings.