A gripping

eye-witness report from Diyarbakir (Amed in Kurdish), the main city of Turkey’s

Kurdistan and the terror inflicted by the Turkish state and its dictator

Erdogan.

eye-witness report from Diyarbakir (Amed in Kurdish), the main city of Turkey’s

Kurdistan and the terror inflicted by the Turkish state and its dictator

Erdogan.

As the Kurds provide the main opposition to Isis, Turkey attacks them whilst remaining part of the ‘anti-Isis alliance’ with Britain and the USA.

Tony

Greenstein (thanks to Moshe Machover)

Greenstein (thanks to Moshe Machover)

In Turkey, the state doesn’t talk—it only shoots

January

9, 2016

9, 2016

A

gripping eyewitness account from Diyarbakir, in southeastern Turkey, where the

state continues its onslaught on the Kurdish civilian population.

gripping eyewitness account from Diyarbakir, in southeastern Turkey, where the

state continues its onslaught on the Kurdish civilian population.

|

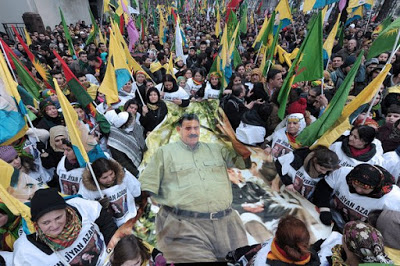

| Mass demonstration in support of release of PKK leader Ocalan |

This article was originally published at Die Wochenzeitung. It was translated from German by Janet Biehl.

It’s freezing cold in

Amed, as the city of Diyarbakir is known to its residents. Over ten centimeters

of snow blankets the ground, something that happens only every three or four

years. And at exactly this moment, fighting is escalating in Amed’s old

neighborhood of Sur and in the cities of Cizre and Silopi, in Sirnak province.

Amed, as the city of Diyarbakir is known to its residents. Over ten centimeters

of snow blankets the ground, something that happens only every three or four

years. And at exactly this moment, fighting is escalating in Amed’s old

neighborhood of Sur and in the cities of Cizre and Silopi, in Sirnak province.

|

| Turkey PKK bus attacked |

I’m

here in the press office of the municipal administration, along with three

journalists and a researcher. These days the office serves as a de facto base

for journalists and researchers from western Turkey and abroad. We talk about

what has been going on in the region for the past few months.

here in the press office of the municipal administration, along with three

journalists and a researcher. These days the office serves as a de facto base

for journalists and researchers from western Turkey and abroad. We talk about

what has been going on in the region for the past few months.

The

events unfolding here are nearly incomprehensible even to those who live here.

Every morning, every evening, and every night a wave of exhaustion pervades my

body as I hear shots, detonations, and explosions from nearby Sur. Also during

the daytime, but them I’m at work.

events unfolding here are nearly incomprehensible even to those who live here.

Every morning, every evening, and every night a wave of exhaustion pervades my

body as I hear shots, detonations, and explosions from nearby Sur. Also during

the daytime, but them I’m at work.

The

others say the same thing, often more dramatically. Many lie awake all night,

every night. Last night a mortar round landed on the roof where one of them is

staying.

others say the same thing, often more dramatically. Many lie awake all night,

every night. Last night a mortar round landed on the roof where one of them is

staying.

In

this city of a million people, we observe with dread how the state, dozens of

times a day, uses tanks and artillery to shoot at the old city, to try to break

the resistance of 200 to 300 young people, organized in the illegal YDG-H. The

state doesn’t speak—it only shoots.

this city of a million people, we observe with dread how the state, dozens of

times a day, uses tanks and artillery to shoot at the old city, to try to break

the resistance of 200 to 300 young people, organized in the illegal YDG-H. The

state doesn’t speak—it only shoots.

Last

spring the Turkish government unilaterally broke off peace negotiations with

the banned PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) and then at the end of July unleashed

war on the PKK. The young people then established “liberated spaces” in several

cities, spaces free of repression. In tandem, the council-democratic

neighborhood people’s councils of Diyarbakir and 20 other places declared

autonomy.

spring the Turkish government unilaterally broke off peace negotiations with

the banned PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) and then at the end of July unleashed

war on the PKK. The young people then established “liberated spaces” in several

cities, spaces free of repression. In tandem, the council-democratic

neighborhood people’s councils of Diyarbakir and 20 other places declared

autonomy.

The

state then began to systematically arrest political activists in North Kurdistan—one

thousand in three weeks alone. Intermittently, between 2009 and 2012, more than

nine thousand people had already been arrested. Many people here want the

long-standing military conflict in the mountains to come to an end. Most are

disgusted that the AKP of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan denied the electoral

success of the leftist-pro-Kurdish party HDP last June and went on to hold a

second election under repressive circumstances.

state then began to systematically arrest political activists in North Kurdistan—one

thousand in three weeks alone. Intermittently, between 2009 and 2012, more than

nine thousand people had already been arrested. Many people here want the

long-standing military conflict in the mountains to come to an end. Most are

disgusted that the AKP of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan denied the electoral

success of the leftist-pro-Kurdish party HDP last June and went on to hold a

second election under repressive circumstances.

|

| Conflict between Army and Kurdish civilians |

Like a bad movie

I’m

on my way home, and it’s still snowing. Tanks roll past me, heading for the old

city. Their effect on the city is terrorizing. This cannot stand. Last spring a

rebellious mood prevailed in the city, after the town of Kobane, in the Kurdish

part of Syria, was liberated. The revolution in Rojava spread its radiance

brightly. Today that feels long ago and far away. Peace was then, war is

now—and this time in the city!

on my way home, and it’s still snowing. Tanks roll past me, heading for the old

city. Their effect on the city is terrorizing. This cannot stand. Last spring a

rebellious mood prevailed in the city, after the town of Kobane, in the Kurdish

part of Syria, was liberated. The revolution in Rojava spread its radiance

brightly. Today that feels long ago and far away. Peace was then, war is

now—and this time in the city!

I

think only in categories of “safe” and “dangerous” places. I feel like I’m in a

bad movie that’s getting worse. Then I remember something an Argentine friend

once said to me, while here making a movie: “There are two surreal places on

this planet: Mexico and Kurdistan.”

think only in categories of “safe” and “dangerous” places. I feel like I’m in a

bad movie that’s getting worse. Then I remember something an Argentine friend

once said to me, while here making a movie: “There are two surreal places on

this planet: Mexico and Kurdistan.”

Up

until October, many HDP members in Amed—where the party got 78 percent of the

vote—questioned the sense of the call for autonomy and all the ditches and

barricades of the young people. They were dumbfounded. And the most political

among them—Amed is a very political city—couldn’t work out a reasonable

analysis. Many asked me, “How long is this going to continue? Will they stop

next month or what?”

until October, many HDP members in Amed—where the party got 78 percent of the

vote—questioned the sense of the call for autonomy and all the ditches and

barricades of the young people. They were dumbfounded. And the most political

among them—Amed is a very political city—couldn’t work out a reasonable

analysis. Many asked me, “How long is this going to continue? Will they stop

next month or what?”

I

think they have awakened from a dream now and are in a state of shock. For a

century, we Kurds have been second-class people. We want peace, I feel that,

but we want a just peace. Even those who lost siblings or children due to the

terror of the state in the last 30 years, as guerrillas or as civilians, desire

peace so strongly that they eagerly believe every spark of hope.

think they have awakened from a dream now and are in a state of shock. For a

century, we Kurds have been second-class people. We want peace, I feel that,

but we want a just peace. Even those who lost siblings or children due to the

terror of the state in the last 30 years, as guerrillas or as civilians, desire

peace so strongly that they eagerly believe every spark of hope.

Many

mistrust the state, which has acted ever more brutally since the summer. Its

acts of cruelty with the recurring curfews—in Sur, since December 1—are

gradually waking the people up. First it was only the political activists, and

now even the residents often say things like “the resistance has begun” and

“there’s nothing left for us now but to fight with dignity.”

mistrust the state, which has acted ever more brutally since the summer. Its

acts of cruelty with the recurring curfews—in Sur, since December 1—are

gradually waking the people up. First it was only the political activists, and

now even the residents often say things like “the resistance has begun” and

“there’s nothing left for us now but to fight with dignity.”

Unfortunately

we have a president who, to an unprecedented degree, is persecuting all

peace-seeking Kurds and non-Kurdish democrats in Western Turkey—they are

perhaps in a greater state of shock than we are—so as to establish himself as

the eternal ruler. We must resist! That may sound like propaganda or a

morale-boosting slogan. But what solution do the critics have? In the past only

resistance has had any effect.

we have a president who, to an unprecedented degree, is persecuting all

peace-seeking Kurds and non-Kurdish democrats in Western Turkey—they are

perhaps in a greater state of shock than we are—so as to establish himself as

the eternal ruler. We must resist! That may sound like propaganda or a

morale-boosting slogan. But what solution do the critics have? In the past only

resistance has had any effect.

And

meanwhile what are the European governments doing? They send President Erdoğan

money so he will detain the refugees in Turkey, and otherwise they shut their

eyes. The EU is once again even talking about accession, to bind Turkey closer

to itself. Suddenly all the criticism of recent years is silenced. Okay, state

politics is crap. But those of you in Europe—you still have a halfway

independent public sphere, which we are losing here. Get to work, and don’t

allow this sordid deal to happen!

meanwhile what are the European governments doing? They send President Erdoğan

money so he will detain the refugees in Turkey, and otherwise they shut their

eyes. The EU is once again even talking about accession, to bind Turkey closer

to itself. Suddenly all the criticism of recent years is silenced. Okay, state

politics is crap. But those of you in Europe—you still have a halfway

independent public sphere, which we are losing here. Get to work, and don’t

allow this sordid deal to happen!

“You’ve killed my mother”

Three

hours later I am translating a letter from a young person from Silopi, Inan,

whose mother was shot in the street last month, and succumbed to her wounds

because for one week the police snipers shot anyone who tried to help her. A

week ago a journalist published the story on the blog of a Turkish newspaper.

This is perhaps the most difficult translation of my life. I want to share it

with you.

hours later I am translating a letter from a young person from Silopi, Inan,

whose mother was shot in the street last month, and succumbed to her wounds

because for one week the police snipers shot anyone who tried to help her. A

week ago a journalist published the story on the blog of a Turkish newspaper.

This is perhaps the most difficult translation of my life. I want to share it

with you.

When

we learned that my mother had been shot, we rushed to the spot. Before we

arrived, my uncle had tried to get to her, but they shot him too. As I arrived,

neighbors were carrying my dead uncle’s body away. I asked about my mother, and

they said she was still lying in the street. When I tried to go to her, they

held me back. I cried, cried, cried. My mother had fallen in the middle of the

street and was just lying there. At first she had moved a little, but then her

movements subsided. Everyone we called—representatives, regional councilors,

provincial governor—said the snipers should withdraw so we could remove her

body.

we learned that my mother had been shot, we rushed to the spot. Before we

arrived, my uncle had tried to get to her, but they shot him too. As I arrived,

neighbors were carrying my dead uncle’s body away. I asked about my mother, and

they said she was still lying in the street. When I tried to go to her, they

held me back. I cried, cried, cried. My mother had fallen in the middle of the

street and was just lying there. At first she had moved a little, but then her

movements subsided. Everyone we called—representatives, regional councilors,

provincial governor—said the snipers should withdraw so we could remove her

body.

What

was my mother feeling as she lay there? She suffered. For seven days she lay in

the street. None of us slept, so we could keep the dogs and birds away from

her; she lay there, 150 meters away, and we saw how she had lost her life. In

those seven days, the state caused us as much suffering as any one human being

can cause to an other.

was my mother feeling as she lay there? She suffered. For seven days she lay in

the street. None of us slept, so we could keep the dogs and birds away from

her; she lay there, 150 meters away, and we saw how she had lost her life. In

those seven days, the state caused us as much suffering as any one human being

can cause to an other.

My

mother still had her shawl in one hand, her hands had become stiff, the

position of her body reflected her struggle to survive. The blood was dry. Her

hands, her face, where she fell to the ground, was covered with dirt, her clothing

was drenched in dried blood.

mother still had her shawl in one hand, her hands had become stiff, the

position of her body reflected her struggle to survive. The blood was dry. Her

hands, her face, where she fell to the ground, was covered with dirt, her clothing

was drenched in dried blood.

The

believers have ripped out the soul of my mother. The eyes of my mother remain

open, her face tilted toward our house. I cannot express how much pain I am

feeling. Seven days in deepest winter she lay in the street. The most painful

thing is not to know how long she stayed alive. I hope she died right away.

They have killed my mother.

believers have ripped out the soul of my mother. The eyes of my mother remain

open, her face tilted toward our house. I cannot express how much pain I am

feeling. Seven days in deepest winter she lay in the street. The most painful

thing is not to know how long she stayed alive. I hope she died right away.

They have killed my mother.

If

you do not feel anything, then reread this letter—over and over.

you do not feel anything, then reread this letter—over and over.

Escalation

In

recent weeks in the Kurdish parts of Turkey, individual cities and

neighborhoods have been transformed into war zones. Hidden from the public,

Turkish military and police forces have moved with heavy weapons against the

rebels, often young people, and do not spare even nonparticipants. Human Rights

Watch has assembled eyewitness accounts showing that the security forces have

opened fire even on those who try to leave their homes. Local human rights

groups report that more than 150 civilians have been killed.

recent weeks in the Kurdish parts of Turkey, individual cities and

neighborhoods have been transformed into war zones. Hidden from the public,

Turkish military and police forces have moved with heavy weapons against the

rebels, often young people, and do not spare even nonparticipants. Human Rights

Watch has assembled eyewitness accounts showing that the security forces have

opened fire even on those who try to leave their homes. Local human rights

groups report that more than 150 civilians have been killed.

After

the parliamentary elections in November, hopes rose that the Turkish government

would end the course of confrontation that it had begun in July. Those hopes

have been dashed. On the contrary, the repression has intensified, even of

elected officials of the pro-Kurdish HDP party. Several of them, including the

co-leader Selahattin Demirtas, have been threatened with charges of separatism.

the parliamentary elections in November, hopes rose that the Turkish government

would end the course of confrontation that it had begun in July. Those hopes

have been dashed. On the contrary, the repression has intensified, even of

elected officials of the pro-Kurdish HDP party. Several of them, including the

co-leader Selahattin Demirtas, have been threatened with charges of separatism.

Ercan Ayboga

Ercan

Ayboga, son of Kurdish-Turkish parents, studied environmental engineering in

Germany. He is active in the Mesopotamian Ecology Movement and works for the

city administration in Diyarbakir as an environmental consultant and in the

international press office.

Ayboga, son of Kurdish-Turkish parents, studied environmental engineering in

Germany. He is active in the Mesopotamian Ecology Movement and works for the

city administration in Diyarbakir as an environmental consultant and in the

international press office.

Posted in Blog