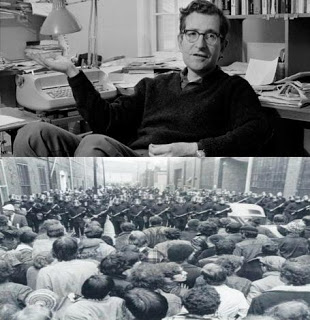

Between the war scientists and the anti-war students

Responsibility of Intellectuals’. Few other writings had a

greater

impact on the turbulent political atmosphere on US campuses in the

1960s. The essay launched Chomsky’s political career as the world’s most

intransigent and cogent critic of US foreign policy – a position he has

held to this day.

No one could doubt Chomsky’s sincerity or his gratitude to the student

protesters who brought the war in Vietnam to the forefront of public

debate. On the other hand, he viewed the student rebels as ‘largely

misguided’, particularly when they advocated revolution.

Referring to the student and worker uprising in Paris in May 1968,

Chomsky recalls that he ‘paid virtually no attention to what was going

on,’ adding that he still believes he was right in this. Seeing no

prospect of revolution in the West at this time, Chomsky

went so far as to describe US students’ calls for revolution as

‘insidious’. While he admired their ‘challenge to the universities’, he

expressed ‘skepticism about how they were focusing their protests and

criticism of what they were doing’ – an attitude that

led to ‘considerable conflict’ with many of them.[1]

As is well known, Chomsky’s university was the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology, where he taught and researched linguistics in one of its

research laboratories funded by the military. Although he sometimes

understates MIT’s military role, Chomsky has never

made a secret of its Pentagon connections. Referring to the 1960s, he

explains that MIT was ‘about 90% Pentagon funded at that time. And I

personally was right in the middle of it. I was in a military lab. If

you take a look at my early publications, they

all say something about Air Force, Navy, and so on, because I was in a

military lab, the Research Lab for Electronics.'[2]

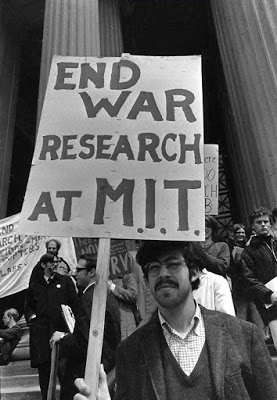

By the late 1960s, MIT’s various laboratories and departments were

researching helicopter design, radar, smart bombs and counterinsurgency

techniques for the ongoing war in Vietnam. In Chomsky’s words: ‘There

was extensive weapons research on the MIT campus.

… In fact, a good deal of the [nuclear] missile guidance technology

was developed right on the MIT campus and in laboratories run by the

university.'[3] One of the radical student newspapers of the time,

The Old Mole, expressed things still more

bluntly:

‘MIT isn’t a center for scientific and social research

to serve humanity. It’s a part of the US war machine. Into MIT flow

over $100 million a year in Pentagon research and development funds,

making it the tenth largest Defense Department R&D contractor

in the country. MIT’s purpose is to provide research, consulting

services and trained personnel for the US government and the major

corporations – research, services, and personnel which enable them to

maintain their control over the people of the

world.'[4]

In the light of this, it is hardly surprising that, according to one

former MIT student, ‘most radical students, as well as many liberal

students, wanted first and foremost to stop the war research.'[5] But in

1969, in a contribution to an official MIT report,

Chomsky took a significantly different position. Resorting to the

language of defense and deterrence favoured by the university’s war

scientists, he proposed that, rather than closing down the military

laboratories, ‘they should be restricted to research on

systems of a purely defensive and deterrent character.’ One of the

leading student activists at MIT at the time, Michael Albert, later

described Chomsky’s cautious position as, in effect, ‘preserving war

research with modest amendments.'[6] (I should point

out, however, that despite their disagreements, Albert remains

supportive of Chomsky to this day, as do other student radicals who have

known Chomsky personally over the years.)

Back in 1969, MIT’s student radicals were keen to take direct action

against the university’s war research by, among other things, occupying

the office of its president, Howard Johnson. Again, Chomsky took a

different position and at one point, according to

one of his academic colleagues, he joined with other professors in

standing in Johnson’s office to prevent the students from occupying it.

As he said later about the 1960s student tactic of occupation, ‘I wasn’t

in favor of it myself, and didn’t like those

tactics.'[7]

MIT’s radicals not only organised occupations, they also organised a

mass picket of the university’s nuclear missile laboratories. Determined

to put a stop to this kind of disruption, the university eventually had

six students sentenced to prison terms.[8]

One of these students, George Katsiaficas, served time for the crime of

‘disruption of classes’. To this day, he remains indignant about his

treatment and says that the phrase, the ‘banality of evil’ – famously

used by Hannah Arendt to describe Nazi war criminals

– applies equally to President Howard Johnson. Adopting a quite

different tone, however, Chomsky told Time magazine

that Johnson was an ‘honest, honourable man’ and it seems he even

attended a faculty party held to celebrate Johnson’s success at

containing

the student protests.[9]

Chomsky has acknowledged that some students did suffer from incidents

‘that should not have happened’. But, while student leader Michael

Albert described MIT as another ‘Dachau’ whose ‘victims burned in the

fields of Vietnam’, Chomsky has again and again defended

the university’s role.[10] In view of the imprisonments, expulsions and

job losses suffered by MIT’s radicals, it is hard to know what to make

of Chomsky’s claim that MIT’s anti-war activists ‘had no problems’ from

the university. Nor is it easy to recognise

his description of MIT as ‘one of the most free universities in the

world’ with ‘the best relations between faculty and students than at any

other university.'[11]

CHOMSKY AND THE WAR CRIMINALS

Still more puzzling was Chomsky’s attitude when Walt Rostow visited MIT

in 1969. Rostow was one of those prominent intellectuals whom Chomsky

had so eloquently denounced in his ‘Responsibility of Intellectuals’

article. As an adviser to both President John

Kennedy and President Lyndon Johnson, Rostow had been one of the main

architects of the war in Vietnam. In particular he was the strategist

responsible for the carpet bombing of North Vietnam.

Against this background, it was hardly surprising that when Rostow

arrived at MIT, his lecture was disrupted by students furious at his

presence on their campus.[12] Far from associating himself with such

student rage, however, when Chomsky heard that Rostow

was hoping to return to his former job at MIT, he actually welcomed the

prospect. Then, when he heard that the university was poised to reject

Rostow’s job application for fear of more student disruption, Chomsky

went to Howard Johnson and threatened to lead

MIT’s anti-war students to ‘protest publicly’ – not against – but

in favour of Rostow being allowed back to the

university.[13]

Rostow wasn’t the only powerful militarist at MIT to receive support

from Chomsky. Twenty years later, Chomsky was, as he says, ‘one of the

very few people on the faculty’ who supported John Deutch’s bid to

become university President.[14] Deutch was particularly

controversial because, as MIT’s radical newspaper, The

Thistle, explained, he was both an ‘advocate of US nuclear

weapons build-up’ and ‘a strong supporter of biological weapons, and of

using chemical and biological weapons together in order to increase

their killing efficiency.’ In fact, by the late 1980s, Deutch had not

only brought chemical and biological weapons research to MIT, he had

apparently ‘pressured junior faculty into performing this research on

campus’.[15]

Fearing that the university was about to become even ‘more

militaristic’, MIT’s radicals – with the notable exception of Chomsky –

joined others on the faculty to successfully block Deutch’s appointment.

Then, later, when President Clinton made Deutch No.2

at the Pentagon and, in 1995, Director of the CIA, student activists

demanded that MIT cut all ties with him. Chomsky once again disagreed,

The New York Times reporting him as saying of

Deutch that ‘he has more honesty and integrity than anyone I’ve

ever met in academic life, or any other life…. If somebody’s got to

be running the CIA, I’m glad it’s him.'[16] Of course, the most

remarkable thing about all this is that, throughout this entire period,

Chomsky was churning out dozens of brilliantly argued

articles and books denouncing the CIA and the US military as criminals,

their hands dripping in blood.

One way of making sense of Chomsky’s various contradictory positions is

to view them in the light of the public statements made by MIT’s

managers at the height of the student unrest in 1969. At this time,

President Howard Johnson described his university as

‘a refuge from the censor, where any individual can pursue truth as he

sees it, without any interference.'[17] Underlying such statements was

Johnson’s anxiety lest MIT’s war scientists suffer ‘interference’ from

protesting students and Johnson himself wasn’t

too consistent in defending this position, readily abandoning it when

he declined Rostow’s request to return to MIT. Unlike Johnson, however,

Chomsky stuck to the university’s principles. He remained true to the

MIT’s non-interference stance, even to the point

of defending the right of a potential war criminal, John Deutch, and an

actual ‘war criminal’ (Chomsky’s description of Walt Rostow) to hold

important posts at the university.[18]

Part of the explanation for all this may have been Chomsky’s reluctance

to fall out with fellow faculty members, especially those with whom he

associated regularly. As he remarked at one point, ‘I’m always talking

to the scientists who work on missiles for

the Pentagon.'[19] But there must have been more to Chomsky’s thinking

than this.

In 1969, one MIT student is reported to have justified his opposition to

the university’s military research on the grounds that ‘one doesn’t

have the right to build gas chambers to kill people’, adding that ‘the

principle that people should not kill other people

is more important than notions of freedom to do any kind of research

one might want to undertake.'[20] Chomsky, by contrast, extended the

principle of academic non-interference to unusual lengths. It was

crucial to him that MIT held strictly to the management

ideal of the university as ‘a refuge from the censor’. After all, a

less libertarian policy might have undermined his own conflicted

position as an anti-war campaigner working in a laboratory funded by the

US military.

None of this makes Chomsky’s opposition to US militarism any less

genuine or admirable. If anything, his dissidence was all the more

remarkable given the context in which it was expressed. My aim here is

simply to highlight how conflicted Chomsky must

have felt, being a committed anti-militarist in an institution so

closely associated with a war machine that was inflicting so much death

and misery across the globe.

Chomsky’s moral qualms were particularly apparent at the height of the

war in Vietnam when, in October 1968, Chomsky told The New

York Times that he felt ‘guilty most of the time’.[21] One

way to assuage this guilt might have been to resign and, as

it happens, around the time that the New York Review of

Books published ‘The Responsibility of Intellectuals’ in its

February 1967 edition, Chomsky was thinking of doing just that. The

March edition of the Review included a letter from

Chomsky

saying he had ‘given a good bit of thought to … resigning from MIT,

which is, more than any other university associated with the activities

of the Department of “Defense”‘. However, Chomsky soon had second

thoughts which he expressed in a follow-up letter

published in the April edition. Whereas in his original letter he had

complained that MIT’s ‘involvement in the war effort is tragic and

indefensible’, in the follow-up he claimed – in a surprising about-turn –

that ‘MIT as an institution has no involvement

in the war effort. Individuals at MIT, as elsewhere, have direct

involvement and that is what I had in mind.'[22]

So it appears that, despite his sincere and often courageous opposition

to the US military, Chomsky felt a simultaneous pull in the opposite

direction, prompting him to tone down criticisms of MIT in order to

protect his ability to continue with the job he

loved. My own view is that the intensity of Chomsky’s anti-militarist

dissidence can be explained in part by his need to square his continued

MIT employment with a political conscience that refused to lie

down.

I have no space in a short article to explain how such moral dilemmas

influenced not only Chomsky’s political work but also his linguistics.

Suffice it to say that Chomsky was hired to work at MIT by Jerome

Wiesner, a military scientist who, in the 1950s, was

arguing ‘fervently for developing and manufacturing ballistic

missiles.’ Wiesner was an adviser both to the CIA and to President

Eisenhower and it is hard to think of anyone in US academia who was more

deeply involved in both the technology and the decision

making of nuclear war than he was.[23]

Wiesner initially employed Chomsky because, as he said, ‘[We wanted to]

use computers to do automatic translation, so we hired Noam Chomsky and

Yehoshua Bar-Hillel to work on it.’ In this Cold War period, the US

military were investing millions of dollars in

linguistic research not only to automatically translate Eastern bloc

documents but also to enhance their computer systems of ‘command and

control’ both for nuclear war and, later, for the war in

Vietnam.[24]

Chomsky, therefore, found himself from the very beginning of his career

working in a largely conservative institutional milieu among colleagues

more or less happy to conduct advanced weapons research. Given his own

political commitments, on the other hand,

he needed to ensure that his own particular contribution would not

assist the military in any way. He solved this problem by extricating

linguistics from practicalities altogether. Language, under Chomsky’s

novel definition, became non-communicative, non-social

and, in effect, little more than a Platonic abstraction. In short, for

fifty years, much of linguistics was driven into an academic dead-end

from which it has taken decades to emerge. But all that is another story

….[25]

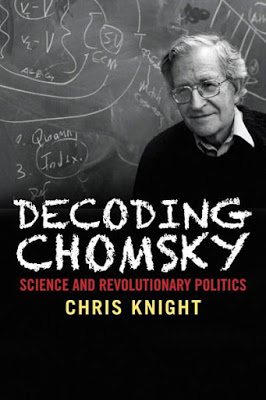

Chris Knight is author of Decoding Chomsky: Science and revolutionary politics (Yale University Press, 2016).

NOTES

1. R.Barsky, Noam Chomsky, a life of dissent, p122, 131.

2. G.D.White, Campus Inc., p445.

3. M.Albert, Remembering Tomorrow, p97-99; C.P.Otero, Noam

Chomsky: Language and Politics (2004), p216. Any

university that restricted its research to the development of military

technology would soon run out of new ideas so MIT does a lot of pure

science, including linguistics. But, as Michael Albert says,

‘War blood ran through MIT’s veins. It flooded the research facilities

and seeped even into the classrooms.’ In the late 1960s, some 500

students worked in MIT’s military laboratories. Most of these students

worked in the Instrumentation Laboratories that

were part of the engineering school and which, in Chomsky’s words, were

only ‘two inches off campus’ with people going ‘between them all the

time’. MIT also did military research ‘on campus’ for both the Navy and

the CIA. Albert p99; MIT

Review Panel on Special Laboratories, Final Report, p59-69; Works And Days 51-4: Vol. 26/27, 2008-09, p533; <em>MIT

Bulletin

, Report of the President, 1969, p237-40, 255; The Tech, 31/10/69, p1, 10.

4. ‘Why

Smash MIT?’, in I.Wallerstein, The University

Crisis Reader, Vol.2 p240-3; Albert p113-4.

5. Stephen Shalom, New Politics, Vol.6(3).

6. MIT Review Panel on Special Laboratories, Final Report, p37-8; Albert p98.

7. J.Segel, Recountings; Conversations with MIT mathematicians, p206-7; N.Chomsky, ‘MIT 150 Infinite History Project’.

8. The Tech, 14/12/71, p8 and The Tech, 4/8/72, p1.

9. www.eroseffect.com/articles/holdingthecenter.pdf</a>; Time, 21/11/69 p68 and 15/3/71

p43; H.Johnson, Holding the Center, p202-3.

10. N.Chomsky, Chomsky on Democracy and Education,

p311; Albert p9, 16. Chomsky’s discomfort with any kind of illegal or

confrontational action at MIT was shown again, in 2011, when the

university cooperated with the prosecution of Aaron Swartz for

the ‘crime’ of downloading Jstor journals from MIT’s library. Although

Jstor agreed to a deal whereby Swartz would avoid prison, MIT apparently

rejected this deal and the threat of decades in prison helped drive

Swartz to suicide. When asked about this tragic

event, Chomsky did say that MIT should have acted differently. However

he also implied that Swartz should have been prosecuted – if only for a

‘misdemeanour’ – and he then said: ‘If you take Jstor and make it

public, Jstor goes out of business … [and] nobody

has access to the journals. … You can’t just liberate things,

pretending you don’t exist in the [capitalist] world.’ ‘Noam Chomsky at the British Library’ (video, at 1hr.30mins.); The

Boston Globe, 15/1/13; The Atlantic, 30/7/13. See also: ‘Passing

Noam on My Way Out, Part 2: Chomsky vs. Aaron Swartz’.

11. The Tech, 14/12/71, p8; N.Chomsky, Class Warfare (1999), p137; White p445-6; R.Chepesiuk,

Sixties Radicals, p145; S.Diamond, Compromised

Campus, p284-5.

12. D.Milne, America’s Rasputin; The Tech, 11/4/69, p1, 8.

13. Barsky p141; >’TV debate between Noam Chomsky and William Buckley’.

14. Chomsky, Class Warfare, p135-6.

15. The Tech, 7/3/89</a>, p2, 16 and 27/5/88, p2, 11; The Thistle, Vol.9

No.7.

16. The Thistle, Vol.9 No.7; The New York Times, 10/12/95.

17. <em>MIT Bulletin

, Report of the President, 1969, p3.

18. J.Wiesner, Jerry Wiesner, p582; Johnson p189-90; Barsky p141.

19. N.Chomsky, Understanding Power

(2013), p10.

21. The New York Times, 27/10/68.

22. New York Review of Books, 25 March and April

1967.

23. The New York Times, 23/10/94; D.Welzenbach, ‘Science

and Technology: Origins of a Directorate’, p16, 21; L.Smullin, ‘Jerome Bert Wiesner, 1915-1994, A Biographical Memoir’, p 1, 7-10, 20; D.L.Snead, Eisenhower and the Gaither Report, p189; M.Rosenberg, Plans and Proposals for the Ballistic

Missile Initial Operation Capability Progam, piii-iv, 6-11, 17-22.

24. S.Garfinkel, ‘Building 20, A Survey’; J.Nielsen, ‘Private

Knowledge, Public Tensions:

Theory commitment in postwar American linguistics’, p 39-42,

194, 338-42; F.J.Newmeyer, The Politics of

Linguistics, p84-6. Wiesner went on to say, ‘It didn’t take

us long to realize that we didn’t know much about language. So we went

from automatic

translation to fundamental studies about the nature of language.’

Wiesner later became critical of US policy on both nuclear weapons and

on the Vietnam war but this did not stop him from continuing to oversee

MIT’s huge military research program which he,

naturally, justified on the grounds of ‘academic freedom’.

The Tech, 28/4/72, p5; L.Kampf, ‘The University in American Power’ (audio, at 48mins.).

25. Another academic dead-end, in the form of postmodernism, befell

cultural theory and it is notable that MIT also played a formative role

in that intellectual disaster. See: B.Geoghegan, ‘From

Information Theory to French Theory’, Critical Inquiry 38 (2011).